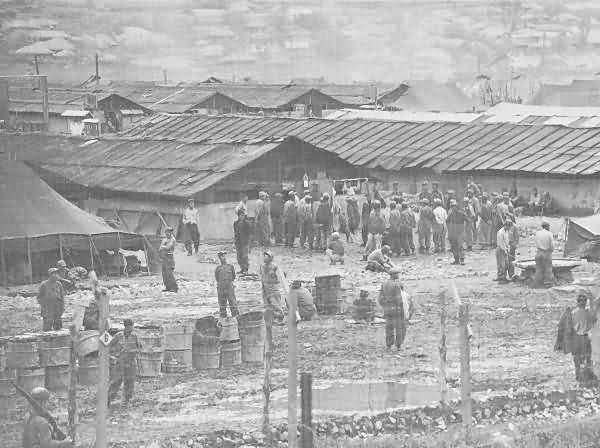

| One of the points of contention which delayed signing of the Armistice was how to deal with POWs who did not wish to be repatriated. We had over 137,000 communist prisoners by January 1952, and about a third of them did not wish to be repatriated, which was a serious embarassment for the enemy. As contrast, the enemy ended up with about 13,500 prisoners from all UN forces, of whom 347 refused repatriation, including 21 Americans. To enflame this situation even further were the events that took place in the UN Command Koje-do POW camp. The Geneva Convention of 1949 on prisoners of war was designed primarily to protect prisoners, and completely failed to foresee the development of hard-core, organized prisoner groups or to provide protection for captor nations in dealing with their stubborn, armed resistance. Whatever attempts UNC made to control them reflected adversely on the UNC in the public view, further weakening our ability to control and restrain the camp compounds. With North Korean and Chinese leaders, including agents who deliberately allowed themselves to be captured in order to organize cells of resistance, the Koje-do compounds soon turned to beatings and other coercion to subjugate disillusioned anti-communist prisoners, including the murder of scores of such prisoners. Attempts to screen the prisoners to decide who wished repatriation led to several bloody riots instigated by the communist leadership, with scores of POWs being killed by UNC troops and others murdered by the communists. Only about 1500 prisoners actually took part in the riots, strongly suggesting that only the hard-core leadership was primarily involved. When UNC teams did begin screening the prisoners beginning April 8 1952, they were astonished to find that only 70,000 of the 170,000 military and civilian prisoners consented to repatriation. This was the root cause for the POW capture of Koje commandant General Dodd. Photos of Koje-do POW compound 76 at this time. |