History  On Line

On Line

Although the situation in the prisoner of war camps did not attain international prominence until May 1952, there had been numerous indications of the potential danger prior to that time. Riots, demonstrations, and violence had become common in the compounds housing the Communist prisoners, but the U.N. Command had preferred to cope with them on a day-to-day basis. The hope that a truce soon would be negotiated and eliminate the need for drastic UNC actions fostered a policy of delay. In turn, the lack of strong UNC measures encouraged the Communist prisoners to become bolder and more demanding. As UNC control dissipated, the enemy prisoners took charge of their compounds and began to plan for a coup that would focus the eyes of the world upon the whole prisoner of war problem.

This remarkable turnabout wherein prisoners dealt with their captors on what amounted to terms of equality must properly begin with the landings at Inch'on in September 1950.

The Seeds Are Planted

After the surprise attack at Inch'on and the follow-up advance by the Eighth Army, the North Korean Army began to fall back. But large numbers of the enemy were taken prisoner in the swift maneuver and sent to the rear. The bag of prisoners rose from under a thousand in August 1950 to over 130,000 in November. Unfortunately, little provision had been made for so many prisoners and facilities to confine, clothe, and feed them were not available. In addition, there were not enough men on hand to guard the prisoners nor were the guards assigned adequately trained for their mission.1 The quantity and quality of the security forces continued to plague the UNC prison-camp commanders in the months that lay ahead.

While the prisoners were housed near Pusan, there was a tendency for former ROK personnel who had been impressed into the North Korean Army and later recaptured by the UNC to take over the leadership in the compounds. Since these ex-ROK soldiers professed themselves to be anti-Communist and were usually favored by the ROK guards, they were able to win positions of power and control.

As the prisoner total reached 137,000 in January 1951, the UNC decided to isolate captured personnel on Koje-do, an island off the southern coast of Korea. But before the move was made, the South Korean prisoners were segregated from the North Koreans. This left a power vacuum in many of the compounds that were abruptly deprived of their leaders.2

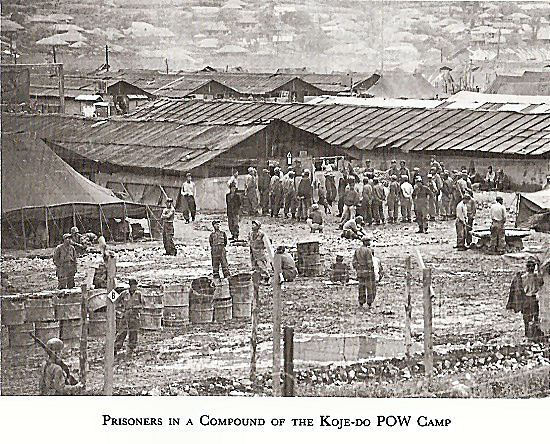

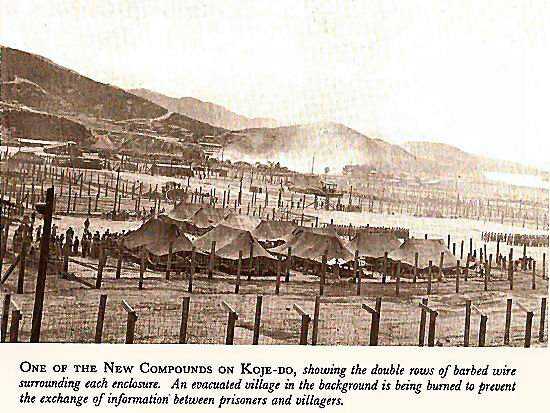

On Koje-do security problems were reduced, but there were serious engineering obstacles to be overcome. Since there were little or no natural water resources on the island, Col. Hartley F. Dame, the first camp commander, had to build dams and store rain water to service the 118,000 natives, 100,000 refugees, and 150,000 prisoners.3 Construction began in January on the first enclosure of UNC Prisoner of War Camp Number 1 and by the end of the month over 50,000 POW's were moved from the mainland to Koje-do.4

Swiftly, in two rock-strewn valleys on the north coast, four enclosures, each subdivided into eight compounds, were built. Originally intended to hold 800-1,2000 men apiece, the compounds were soon jammed to five times their capacity. Since available land was at a premium on the island, the space between the compounds soon had to be used to confine the prisoners too. This conserved the construction of facilities and the number of guards required to police the enclosures, but complicated the task of managing the crowded camp. Packing thousands of men into a small area with only barbed wire separating each compound from the next permitted a free exchange of thought and an opportunity to plan and execute mass demonstrations and riots. With the number of security personnel limited and usually of inferior caliber, proper control was difficult at the outset and later became impossible. But the elusive hope of an imminent armistice and a rapid solution of the prisoner problem delayed corrective action.5

It is only fair to point out that although there were frequent instances of unrest and occasional outbreaks of resistance during the first months of the Koje-do prison camp's existence, much of the early trouble could be traced to the fact that ROK guards were used extensively. Resentment between ROK and North Korean soldiers flared into angry words, threats, and blows very easily. Part of the tension stemmed from the circumstance that at first the prisoners drew better rations than the guards, but eventually this discrepancy was adjusted. In the internecine disputes the U.S. security troops operated at a disadvantage since they knew little or no Korean and were reluctant to interfere. Bad blood between guards and prisoners, however, formed only one segment of the problem.

Although the United States had not ratified the Geneva Convention of 1949 on prisoners of war, it had volunteered to observe its provisions.6 The Geneva Convention, however, was designed primarily to protect the rights of the prisoners. It completely failed to foresee the development of hard-core, organized prisoner groups such as those that grew up on Koje-do in 1951-52 or to provide protection for the captor nation in dealing with stubborn resistance. In their zeal for defending the prisoners from hardship, injustice, and brutality, the makers spelled out in detail the privileges of the prisoners and the restrictions upon the captor nation, but evidently could not visualize a situation in which the prisoners would organize and present an active threat to the captor nation.7 Under these conditions every effort at violence by the prisoners that was countered by force reflected badly upon the U.N. Command. Regardless of the provocation given by the prisoners, the UNC appeared to be an armed bully abusing the defenseless captives and the Communists capitalized on this situation.

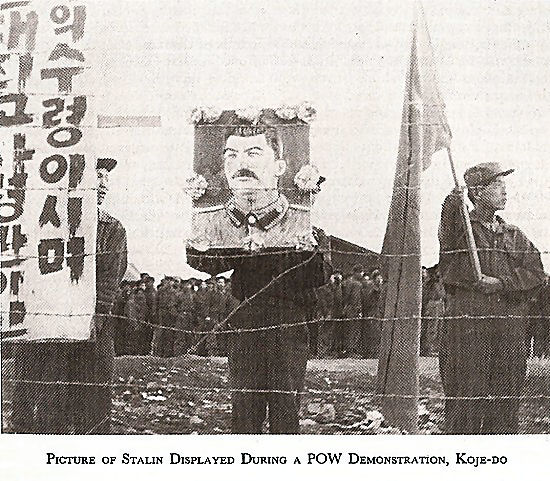

The outbreaks of dissension and open resistance were desultory until the negotiations at Kaesong got under way. Then the prisoners realized that their future was at stake. Many had professed strong anti-Communist sentiments and were afraid to return, while others, anticipating repatriation, swung clearly to the side of Communist groups in the compounds. From North Korea, agents were sent to the front lines and permitted themselves to be captured so that they could infiltrate the prison camps. Working through refugees, civilians, and local guerrillas, the agents were able to keep in touch with their headquarters and to plan, organize, and stage incidents at will. Inside the camps, messages were passed visually by signals, hurled by rocks from compound to compound, or communicated by word of mouth. The hospital compound served as a clearinghouse for information and was one of the centers of Communist resistance. Although the agents wielded the actual power in the compounds, they usually concealed themselves behind the nominal commanders and operated carefully to cloak their identities. And behind the agents stood their chiefs, none other than Lt. Gen. Nam Il and Maj. Gen. Lee Sang Cho, the principal North Korean delegates to the armistice conference.8 The close connection between Panmunjom and the prison camps provided another instance of the Communists' untiring efforts in using every possible measure to exert pressure upon the course of the armistice talks.

As the Communists struggled for control of the compounds, a defensive countermovement was launched by the non-Communist elements. Former Chinese Nationalist soldiers and North Korean anti-Communists engaged in bloody clashes with their opponents. When oral persuasion failed, there was little hesitancy on both sides to resort to fists, clubs, and homemade weapons. Kangaroo courts tried stubborn prisoners and sentences were quick and often fatal. Since UNC personnel did not enter the compounds at night and the prisoners were usually either afraid or unwilling to talk, the beatings and murders went unpunished.9 It should also be noted that even if the beaten prisoners had been willing to give evidence against their attackers, as sometimes happened, the camp commander was not in a position to prosecute. He was not permitted by his superiors in Washington to institute judicial procedures against the culprits. Deprived of this weapon of disciplinary control, the prison command was forced to operate under a distinct disadvantage.10

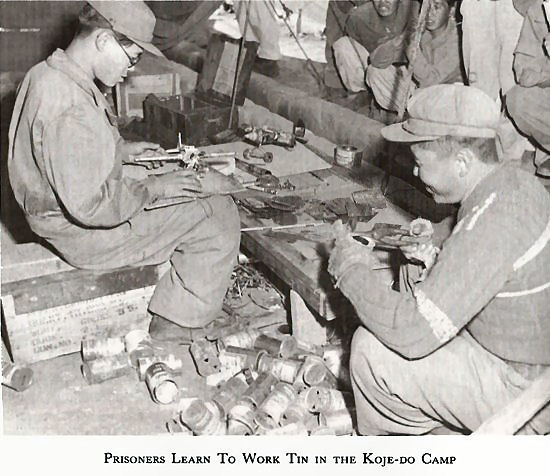

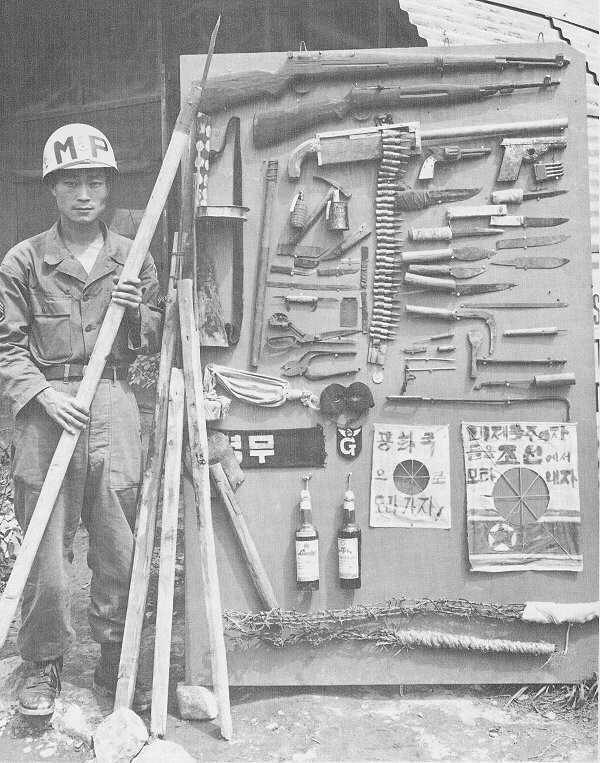

Another instance in which higher headquarters contributed unwittingly to the discontent of the prison camp stemmed from an information and education program instituted in 1951 to keep the prisoners occupied profitably. For the Communists the orientation course became the chief target of criticism and abuse. Although attendance at these lectures was purely voluntary, the subject matter contrasted the advantages of democracy with the fallacies of communism in an unmistakable manner and the Communists protested vehemently. It should be noted that by far the greater portion of the education program aimed at assisting the prisoners in developing vocational and technical skills to help them after their release.11 The Communists readily accepted the instruction in metalworking and soon began to produce weapons of all varieties instead of sanitation utensils, stoves, and garden tools and used these arms to gain interior control in the compounds whenever they could.

In September 1951 fifteen prisoners were murdered by a self-appointed people's court. Three more were killed when rioting broke out on the 19th in Compound 78. Troops had to be rushed in to restore order and remove two hundred prisoners who were in fear of their lives. As unrest mounted, the 2d Logistical Command, in charge of all prison camps, asked Van Fleet for more security personnel. Pointing out that protracted confinement, uncertainty over the future, and Communist agitation against the UNC information and education program had combined to produce increasing tension among the prisoners, the chief of staff of the 2d Logistical Command also reminded Van Fleet that the caliber of the guard troops left much to be desired.12

The September disturbances led to a visit by Van Fleet and a reinforcing and reorganization of the prison security forces. From the opening of the camp in January down to mid-September when Col. Maurice J. Fitzgerald assumed command, there had been eight different commanders or about one a month. As Fitzgerald later commented, "Koje-do was a graveyard of commanders."13 Van Fleet's recognition of the difficulties of. the problems led to the activation of the 8137th Military Police Group in October. Besides three assigned battalions, four additional escort guard companies were attached to the group. In November one battalion of the 23d Infantry Regiment was made available for duty on Koje-do and by December over 9,000 U.S. and ROK personnel were stationed on the island. This was still some 6,000 fewer then the number requested.14

During December the rival factions- Communist and anti-Communist- vied for control of the compounds with both sides meting out beatings and other punishment freely. A large-scale rock fight between compounds on 18 December was followed by riots and demonstrations. Fourteen deaths and twenty-four other casualties resulted from this flare-up.15

The acceleration of violence could be attributed in large part to the inauguration of the screening process in the prison camps. General Yount, commanding the 2d Logistical Command, later told the Far East commander: "Until the inception of the screening program, American personnel had full access to compounds and were able to administer them in a satisfactory manner although never to the degree desired."16

In November and December over 37,000 prisoners had been screened and reclassified as civilian internees.17 As more prisoners indicated that they did not wish to be repatriated or evinced antiCommunist sympathies, the sensitivity of the Communist prisoners to screening intensified. Thus, when the commander of Koje-do camp decided early in January 1952 to give the civilian internees a second screening, the basic ingredients for trouble were on hand. The object of the second round of interviews by ROK civilian teams was to correct the mistakes made in the first series and also to segregate the nonrepatriates from the staunch Communist elements.

Despite numerous incidents all the civilian internee compounds were screened during January and early February except for the 5,600 inmates of Compound 62. Here the Communists had firm control and refused to permit the teams to enter. The compound leader stated flatly that all the members of Compound 62 desired to return to North Korea and there was no sense in wasting time in screening. Since the ROK teams were equally determined to carry out their assignment, the 3d Battalion of the 27th Infantry Regiment moved in during the early hours of 18 February and took up positions in front of the compound.18 With bayonets fixed, the four companies passed through the gate and divided the compound into four segments. But the Communists refused to bow to the show of force. Streaming out of the barracks, they converged on the infantry with pick handles, knives, axes, flails, and tent poles. Others hurled rocks as they advanced and screamed their defiance. Between 1,000-1,500 internees pressed the attack and the soldiers were forced to resort to concussion grenades. When the grenades failed to stop the assault, the UNC troops opened fire. Fifty-five prisoners were killed immediately and 22 more died at the hospital, with over 140 other casualties as against 1 U.S. killed and 38 wounded. This was a high price for the Communists to pay, but human life counted for little. In any event the Communists won their point, for the infantry withdrew and the compound was not screened.19

The fear that the story might leak out to the Communists in a distorted version led the U.N. Command to release an official account placing the blame squarely on the shoulders of the Communist compound leaders. The Department of the Army instructed Ridgway to make it clear that only 1,500 of the inmates took part in the outbreak and that only civilian internees- not prisoners of war- were involved.20 In view of the outcry that the Communist delegates at Panmunjom were certain to make over the affair, this was an especially important point. Civilian internees could be considered an internal affair of the ROK Government and outside the purview of the truce conference.21

But Communist protests at Panmunjom were not the only results of the battle of Compound 62. On 20 February Van Fleet appointed Brig. Gen. Francis T. Dodd as commandant of the camp to tighten up discipline, and the following week Van Fleet received some new instructions from Tokyo:

In regard to the control of the POW's at Koje-do, the recent riot in Compound 62 gives strong evidence that many of the compounds may be controlled by the violent leadership of Communists or anti-Communist groups. This subversive control is extremely dangerous and can result in further embarrassment to the U.N.C. Armistice negotiations, particularly if any mass screening or segregation is directed within a short period of time. I desire your personal handling of this planning. I wish to point out the grave potential consequences of further rioting, and therefore the urgent requirement for the most effective practicable control over POW's.22

Although the orders from Ridgway covered both Communists and antiCommunists, the latter were co-operative in their relations with the UNC personnel and ruthless only when they encountered Communist sympathizers in their midst. The hatred between the two groups led to another bloody encounter on 13 March. As an anti-Communist detail passed a hostile compound, ardent Communists stoned the detail and its ROK guards. Without orders the guards retaliated with gunfire. Before the ROK contingent could be brought under control, 12 prisoners were killed and 26 were wounded while 1 ROK civilian and 1 U.S. officer, who tried to stop the shooting, were injured.23

April was a momentous month for the prisoners on Koje-do. On 2 April the Communists showed their interest in finding out the exact number of prisoners that would be returned to their control if screening was carried out. Spurred by this indication that the enemy might be willing to break the deadlock on voluntary repatriation, the U.N. Command inaugurated a new screening program on 8 April to produce a firm figure.24 During the days that followed, UNC teams interviewed the prisoners in all but seven compounds, where 37,000 North Koreans refused to permit the teams to enter. As noted previously, the results of the screening amazed even the most optimistic of the UNC when only about 70,000 of the 170,000 military and civilian prisoners consented to go back to the Communists voluntarily. The enemy, on the other hand, was at first stunned and then became violently indignant, having been led to expect that a much higher percentage of repatriates would be turned up by the screening. Negotiations at Panmunjom again came to a standstill and the Communists renewed their attack upon the whole concept of screening. In view of the close connection between the enemy truce delegates and the prison camps, it was not surprising that the agitation of the Communists over the unfavorable implications of the UNC screening should communicate itself quickly to the loyal Communist compounds.

During the interviewing period, Van Fleet had informed Ridgway that he was segregating and removing the anti-Communist prisoners to the mainland. Although the separation would mean more administrative personnel and more equipment would be required to organize and supervise the increased number of camps, Van Fleet felt that dispersal would lessen the possibility of incidents.25 Segregation and dispersal, however, had a negative side as well, for the removal of anti-Communists and their replacement by pro-Communists in the compounds on Koje-do could not help but strengthen the hand of the Communist compound leaders. Relieved of the necessity to conduct internecine strife, they could now be assured of wholehearted support from the inmates of their compounds as they directed their efforts against the U.N. Command. An energetic campaign to discredit the screening program backed by all the Communist compounds was made easier by the transfer of the chief opposition to the mainland and the alteration of the balance of power on the island.

In addition to the general political unrest that permeated the Communist enclosures, a quite fortuitous element of discontent complicated the scene in early April. Up until this time responsibility for the provision of the grain component of the prisoners' ration had rested with the ROK Army. But the ROK Government informed the Eighth Army in March that it could no longer bear the burden and Van Fleet in turn told the 2d Logistical Command that it would have to secure the grain through U.S. Army channels. Unfortunately, the U.N. Civil Assistance Command could not supply grain in the prescribed ratio of one-half rice and one-half other grains without sufficient advance time to fill the order. Instead a one-third rice, one-third barley, and one-third wheat ration was apportioned to the prisoners in April and this occasioned an avalanche of complaints.26

The 17 compounds occupied by the Communist prisoners at the end of April included 10 that had been screened and 7 that had resisted all efforts to interview them. There was little doubt in Van Fleet's mind that force would have to be used and casualties expected if the recalcitrant compounds were to be screened.27 As he prepared plans to use force, Van Fleet warned Ridgway on 28 April that the prisoners already screened would probably demonstrate violently when UNC forces moved into the compounds still holding out. In anticipation of trouble Van Fleet moved the 3d Battalion of the 9th Infantry Regiment to Koje-do to reinforce the 38th Infantry Regiment and ordered the 1st Battalion of the 15th Infantry Regiment and the ROK 20th Regiment to Pusan. Barring accident, he intended to begin screening shortly after the 1st of May.28

Confronted with almost certain violence, Ridgway decided to ask for permission to cancel forced screening:

These compounds are well organized and effective control cannot be exercised within them without use of such great degree of force as might verge on the brutal and result in killing and wounding quite a number of inmates. While I can exercise such forced screening, I believe that the risk of violence and violence involved, both to U.N.C. personnel and to the inmates themselves, would not warrant this course of action. Further, the unfavorable publicity which would probably result . . . would provide immediate and effective Communist material. . . 29

This request and Ridgway's plan to list the prisoners in the unscreened compounds as desiring repatriation were approved. Although failure to interview all the inmates in these enclosures might well prevent some prisoners from choosing nonrepatriation, Ridgway's superiors held that if the prisoners felt strongly enough about not returning to Communist control, they would somehow make their wishes known.30

As forced screening was cast into limbo, the prospects for a relaxation of tension on Koje-do should have improved. But in early May, after a tour of inspection, Col. Robert T. Chaplin, provost marshal of the Far East Command, reported that there was a dangerous lack of control within the Communist compounds, with the prisoners refusing even to bring in their own food and supplies. The possibility of new incidents that might embarrass the U.N. Command, especially at Panmunjom, led Ridgway to remind Van Fleet that proper control had to be maintained regardless of whether screening was conducted or not.31 As it happened, Van Fleet was more concerned over the fact that Colonel Chaplin had not informed Eighth Army of his impressions first than he was over the prisoner-camp situation. There was no cause for "undue anxiety" about Koje-do, he told Ridgway on 5 May.32

Actually Eighth Army officers admitted freely that UNC authorities could not enter the compounds, inspect sanitation, supervise medical support, or work the Communists prisoners as they desired. They exercised an external control only, in that UNC security forces did prevent the prisoners from escaping.33 Thus, on 7 May the Communist prisoners and the UNC appeared to have reached a stalemate. The former had interior control, but could not get out without violence; and the latter had exterior control, but could not get in without violence. With the cancellation of forced screening, the U.N. Command indicated that it was willing to accept the status quo rather than initiate another wave of bloodshed in the camps. The next move was up to the Communists.

The Time of Ripening

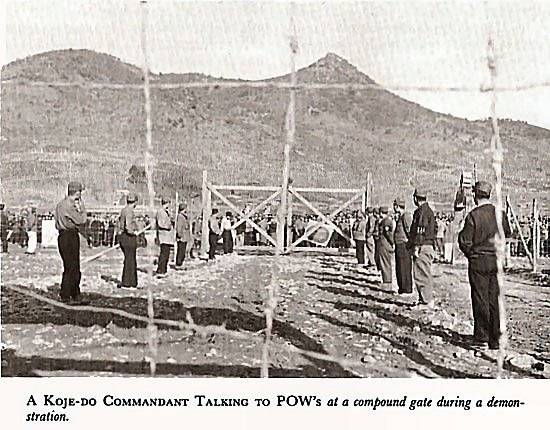

It did not take long for the Communist prisoners to act. As investigation later revealed, they had become familiar with the habits of General Dodd, the camp commandant, during the spring and by the beginning of May they had readied a plan. Well aware that Dodd was anxious to lessen the tension in the camp, they also knew that he often went unarmed to the sally ports of the compounds and talked to the leaders. This system of personal contact kept Dodd in close touch with camp problems, but it exposed him to an element of risk. Only the guards carried weapons on Koje-do and there were no locks on the compounds gates, since work details were constantly passing in and out. Security personnel were not authorized to shoot save in case of grave emergency or in self-defense, and were not permitted to keep a round in the chamber of their guns. In the past the Communists had successfully kidnapped several UNC soldiers and although they had later released them unharmed after Communist complaints had been heard, the practice was neither new nor unknown. Since the technique had proved profitable in previous instances, the enemy prisoners evidently decided to spread their net for the biggest fish of all- the camp commandant. Taking advantage of his willingness to come to them, they made careful plans.34

On the evening of 6 May members of a Communist work detail from Compound 76 refused to enter the enclosure until they had spoken to Lt. Col. Wilbur R. Raven, commanding officer of the 94th Military Police Battalion and the compound. The prisoners told Raven that guards had beaten members of the compound and searched them for contraband. When he promised to investigate the charges, they seemed satisfied, but asked to see General Dodd on the next day to discuss matters of importance. Raven was noncommittal since he did not wish the prisoners to imagine that they could summon the commandant at will, but he promised to pass the message on to the general.35

Since the prisoners indicated that they would be willing to let themselves be listed and fingerprinted if Dodd would come and talk to them, the trap was shrewdly baited. Dodd had just been instructed to complete an accurate roster and identification of all the remaining prisoners of war on Koje-do and the chance to win a bloodless victory was too good to be missed.

Colonel Raven finished his discussions with the leaders of Compound 76 shortly after 1400 on 7 May and Dodd drove up a few minutes later. As usual they talked with the unlocked gate of the sally port between them and the Communists launched a whole series of questions concerning items of food and clothing they felt they should be issued. Then branching into the political field they asked about the truce negotiations. Several times they invited Dodd and Raven to come inside and sit down so that they could carry on the discussion in a more comfortable atmosphere. Raven turned down these suggestions bluntly since he himself had previously been seized and held. More prisoners had meanwhile gathered in the sally port and Dodd permitted them to approach and listen to the conversation. In the midst of the talk, a work detail turning in tents for salvage came through the sally port and the outer door was opened to let them pass out. It remained ajar and the prisoners drew closer to Dodd and Raven as if to finish their discussion. Suddenly they leaped forward and began to drag the two officers into the compound. Raven grabbed hold of a post until the guards rushed up and used their bayonets to force the prisoners back, but Dodd was hauled quickly inside the compound, whisked behind a row of blankets draped along the inner barbed wire fence, and hurried to a tent that was prepared for him. The prisoners told him that the kidnapping had been planned and that the other compounds would have made an attempt to seize him if the opportunity had arisen.36

With the successful completion of the first step disposed of, the Communists lost no time in carrying out the second phase. Within a few minutes of Dodd's capture, they hoisted a large sign announcing- "We capture Dodd. As long as our demand will be solved, his safety is secured. If there happen brutal act such as shooting, his life is danger."37 The threat was soon followed by the first note from Dodd that he was all right and asking that no troops be sent in to release him until after 1800.38 Apparently General Dodd felt that he could persuade the prisoners to let him go by that time.

| One of the most humiliating events for the UNC in the Korean War took place on May 7, 1952, when camp commandant General Dodd was trapped, taken prisoner and put on trial by the communist leaders of compound 76.

|

|

| Rather than forcing a military solution which would have cost the General's life as well as that of untold numbers of the prisoners, replacement commandant General Colson and the reinforced 38th Infantry Regiment sat and watched as the communists put General Dodd on trial on criminal charges for abuse of prisoners, a farce unequalled in modern military history. After winning as many concessions as they thought they could obtain, the communists finally released General Dodd, unhurt in body but doubtless in mental agony for the remainder of his life. |

In the meantime word had passed swiftly back to General Yount, the commanding general of the 2d Logistical Command, and through him to Van Fleet, of the capture of Dodd. Van Fleet immediately instructed Yount not to use force to effect Dodd's release unless Eighth Army approved such action. Yount in turn sent his chief of staff, Col. William H. Craig, by air to Koje-do to assume command.39Repeating Van Fleet's injunction not to use force, Yount told Craig: "We are to talk them out. Obviously if somebody makes mass break we most certainly will resist . . . . But unless they attempt such a thing, under no circumstances use fire to get them out. Wait them out. One thing above all, approach it calmly. If we get them excited only God knows what will happen."40 The fear of a concerted attempt to break out of the compounds and the resultant casualties that both the UNC and prisoners would probably suffer dominated this conversation and mirrored the first reaction of Dodd's superiors to the potential explosiveness of the situation. A major uprising would mean violence and unfavorable publicity that the enemy would exploit.

Dodd's actions in Compound 76 complemented this desire to localize the incident. He consented to act as go-between for the prisoners and relayed their demands to the outside. A telephone was installed and upon Dodd's recommendation, representatives from all of the other compounds were brought to Compound 76 for a meeting to work out the demands that would be submitted to the U.N. Command. Colonel Craig attempted to use one of the senior North Korean officers, Col. Lee Hak Koo, to talk inmates of Compound 76 into releasing Dodd, but Lee, as soon as he was permitted to enter the compound, remained and became the spokesman of the prisoners.41

As the Communist representatives met on the night of the seventh, Dodd urged that no troops be employed to get him since he did not think he would be harmed.42 This was a reasonable assumption, since if anything happened to Dodd, the Communists would have nothing to bargain with. In any event, Dodd's plea coincided with the wishes of Yount and Van Fleet at this point. Colonel Craig, stalling for time, agreed to sit tight. With the UNC troops under general alert orders, the night of 7 May passed uneasily.43

One fact seemed evident-the Communists had won the first round. Not only had they managed to kidnap Dodd, but they had also succeeded in using him to open negotiations. Playing upon the UNC fears of a general breakout of prisoners and the concern over Dodd's life, they pressed their advantage to the hilt.

As the prisoner representatives reconvened the next day, they presented Dodd with a list of their demands. The chief preoccupation of the prisoners during this early phase concerned the formation and recognition by the UNC of an association of the prisoners with telephone facilities between the compounds and two vehicles for intracompound travel. Dodd consented to most of the items of equipment that the prisoners were insisting upon even though he had no command authority to make any agreements. After the meeting concluded, the representatives wanted to return to their compounds and report to the rest of the prisoners; thus another delay ensued. General Yount refused to allow them to leave until Van Fleet overruled him late in the afternoon. By the time the representatives discussed events with their compound mates and returned to Compound 76, evening had begun.44

While the prisoners were carrying on their conversations, Colonel Craig sent for trained machine gun crews, grenades, and gas masks. The 3d Battalion of the 9th Infantry Regiment boarded an LST (landing ship, tank) at Pusan and set out for Koje-do. ROK Navy picket boats ringed the island in case of a major escape attempt and Navy, Marine, and Air Force planes remained on alert. Company B of the 64th Medium Tank Battalion was detached from the 3d Infantry Division and started to rumble toward Pusan. And from the U.S. I Corps, Van Fleet sent Brig. Gen. Charles F. Colson, chief of staff, to take charge of the camp and get Dodd out. The selection of a combat leader to resolve the crisis indicated that a military solution would now be tried. Colson had no knowledge of conditions on Koje-do until he was chosen and only a sketchy acquaintance with the issues being discussed at Panmunjom.45

As Colson assumed command, Van Fleet confirmed this impression that military measures would now be employed. His first instructions to Yount set forth the steps to be followed quite clearly. First official written demands were to be delivered to Compound 76 asking that Dodd be freed immediately. At the same time the prisoners would be informed that Dodd no longer was in command and could make no decisions. If they refused to let him go, Yount would set a time limit and warn the Communists that they would be held responsible for Dodd's safety when force was used. As soon as the deadline expired, Yount would enter the compound by force, release Dodd, and gain full control.46 Yount passed Van Fleet's orders on to Colson late on 8 May.

There were other factors that had to be considered as the drama unfolded. Within the compound Dodd was treated royally. The prisoners did all they could to provide him with small comforts and permitted medicine for his ulcers to be brought in. They applied no physical pressure whatsoever, yet they left no doubt that Dodd would be the first casualty and that they would resist violently any attempt to rescue him by force. Under the circumstances they expected Dodd to co-operate and help them reach a bloodless settlement and Dodd decided to comply.

Early on the morning of 9 May Colson sent in his first official demand for Dodd's safe deliverance and six hours later he issued a second order. When Col. Lee Hak Koo finally responded, he countered with the statement that Dodd had already admitted that he had practiced "inhuman massacre and murderous barbarity" against the prisoners. Recognizing Colson as the new camp commander, Lee asked him to join Dodd at the compound meeting.47 Obviously, the Communists had no intentions of letting Dodd go until they had resolved their differences with the U.N. Command.

The refusal of the prisoners to meet Colson's order should have led to the presentation of an ultimatum with a time limit, but Colson decided to wait until the tanks arrived from the mainland before he tried force. Since the tanks would not arrive until late on the 9th, the action to bring the compound into line could not begin until the following morning. Both Yount and Maj. Gen. Orlando Mood, chief of staff of the Eighth Army, agreed to this postponement.48 In the meantime Colson intended to put a halt to further concessions to the prisoners; his first move in this direction was to stop the POW representatives from circulating back and forth between their compounds and Compound 76.49

Perturbed by the stiffening attitude of Colson and the apparent preparations for action around the compound, the Communists evidently became nervous and had Dodd ask Colson whether they could hold their meeting without fear of interruption. They again promised that Dodd would be freed after the meeting if all went well. Since the U.N. Command was not going to make a move until 10 May anyway, the prisoners were informed that they could meet in safety.50

As the prisoners convened on the 9th, the capture of Dodd assumed a new perspective. They informed their hostage that they were going to discuss the alleged brutalities committed against their members, repatriation and screening, as well as the prisoner of war association.51 Whether the expansion of the Communists' objectives was spurred by their success in using Dodd and the willingness of the UNC to negotiate or was a planned development is difficult to determineit may well have been a combination of these elements that emboldened them to press their luck.

Setting themselves up as a people's court, the prisoners drew up a list of nineteen counts of death and/or injury to compound inmates and had Dodd answer to each charge. Although they were generally disposed to accept his explanations and dismiss the accusations, the spectacle of prisoners, still captive and surrounded by heavily armed troops, trying the kidnapped commanding officer of the prison camp on criminal counts and making him defend his record was without parallel in modern military history.52

While the Communists sat in judgment upon Dodd, Colson had the 38th Infantry Regiment reinforce the guards on all the compounds and had automatic weapons set up in pairs at strategic locations. He directed Lt. Col. William J. Kernan, commanding officer of the 38th, to prepare a plan for forcible entry into Compound 76, using tanks, flamethrowers, armored cars, .50-caliber multiple mounts, tear gas, riot guns, and the like, with a target date of 1000 on 10 May.53

| In the early afternoon, Van Fleet flew into Koje-do for a conference. He had discussed the situation with Ridgway and his appointed successor, General Mark W. Clark, who had just arrived in the Far East, and they were all agreed that no press or photo coverage of the emergency would be permitted.54 They wanted Colson to be sure to give every opportunity to nonbelligerent prisoners to surrender peaceably while he engaged in battle for control of the compound. Van Fleet added that he did not think that U.S. troops should go into the compound, until firepower from the outside had forced obedience and driven the prisoners into small adjacent compounds that had been constructed in the meantime. If necessary he was willing to grant the prisoners' request for an association with equipment and communication facilities, but he reminded Colson that he had full authority to use all the force required to release Dodd and secure proper control and discipline. Regardless of the outcome of this affair, Van Fleet wanted dispersion of the compounds carried out. He left the timing of the Compound 76 operation in Colson's hands, but the negotiating period should end at 1000 on 10 May.55 |

Dodd's trial dragged on through the afternoon as the translation process was slow and laborious. By dusk it was evident that the proceedings would not finish that night and Dodd phoned Colson asking for an extension until noon the next day. He felt that they would keep their promise to let him go as soon as the meeting finished. But Eighth Army refused to alter the 1000 deadline and Colson passed the word back to Dodd. It was at this point that the Communists asserted that they had intended to conduct meetings for ten days, but in the light of the UNC stand they would attempt to complete their work in the morning.56

During the night of 9-10 May, twenty tanks, five equipped with flamethrowers, arrived on Koje-do and were brought into position. Extra wire was laid and the sixteen small compounds were ready to receive the prisoners of Compound 76. All of the guns were in place and gas masks were issued; the last-minute preparations were completed and the troops tried to get some rest. When Dodd and Colson spoke to each other for the last time that night, they said goodbye, since neither expected Dodd to be alive when the operation was over.57

There was another dampening note as heavy rain began shortly after dark and came down steadily all night. As dawn signaled its arrival, fog obscured the compounds. Yet Colson was ready to go in despite the weather. He held out little hope to Yount that the Communists would release Dodd since this would be "silly" on their part and he placed little trust in their good faith.58

But as daylight broke on the tense island the prisoners' latest demands reached Colson. Since he and Dodd had already agreed to most of the eleven requests on the prisoner of war association, the Communists wasted little time on this matter. Instead they directed their attack against UNC prisoner policy, repatriation, and screening. Although the English translation is awkward and some of the phrases difficult to understand, this bold demand deserves quotation in full.

1. Immediate ceasing the barbarous behavior, insults, torture, forcible protest with blood writing, threatening, confinement, mass murdering, gun and machine gun shooting, using poison gas, germ weapons, experiment object of A-Bomb, by your command. You should guarantee PW's human rights and individual life with the base on the International Law.

2. Immediate stopping the so-called illegal and unreasonable volunteer repatriation of NKPA and CPVA PW's.

3. Immediate ceasing the forcible investigation (Screening) which thousands of PW's of NKPA and CPVA be rearmed and failed in slavery, permanently and illegally. 4. Immediate recognition of the P.W. Representative Group (Commission) consisted of NPKA and CPVA PW's and close cooperation to it by your command. This Representative Group will turn in Brig. Gen. Dodd, USA, on your hand after we receive the satisfactory declaration to resolve the above items by your command. We will wait for your warm and sincere answer.59

The Communist objectives were now fully in the open, for admission by the U.N. Command of the validity of the first three demands would discredit the screening process and repatriation policy backed so strongly by the UNC delegation at Panmunjom. If the UNC was violating the Geneva Convention and conducting a reign of terror in the prison camps, as the Communist prisoners charged, then how much reliance could the rest of the world place in the screening figures released by the United Nations Command?

Colson had already sent a final request to Compound 76 to free Dodd, but the receipt of the four demands and of two other pieces of information gave him pause. A disturbing report from his intelligence officer indicated that the other compounds were ready to stage a mass breakout as soon as he launched his attack and, as if to substantiate this item, the native villages near the compound were deserted.60 The prospect of a large number of casualties, on both sides, including General Dodd, decided Colson. Since the UNC had not committed most of the charges leveled by the prisoners, he called Yount and simply told him that Colson could inform Dodd that the accusations were not true. Colson was willing to recognize the POW association, but had no jurisdiction over the problem of repatriation. If Yount could get authority to renounce nominal screening, Colson thought he could fashion an answer acceptable to the prisoners. General Mood felt that nominal screening could be dropped and gave his approval to Yount to go ahead.61

Naturally the Communists wanted Colson's answer in writing and this destroyed any hope of meeting the 1000 deadline. For some reason the translator available to Colson was not particularly quick or accurate and this slowed down the negotiating process.62 At any rate, Colson postponed taking action and sent off an answer to the prisoners:

1. With reference to your item 1 of that message, I am forced to tell you that we are not and have not committed any of the offenses which you allege. I can assure you that we will continue in that policy and the prisoners of war can expect humane treatment in this camp.

2. Reference your item two regarding voluntary repatriation of NKPA and CPVA PW, that is a matter which is being discussed at Panmunjom, and over which I have no control or influence.

3. Regarding your item three pertaining to forcible investigation (screening), I can inform you that after General Dodd's release, unharmed, there will be no more forcible screening of PW's in this camp, nor will any attempt be made at nominal screening.

4. Reference your item four, we have no objection to the organization of a PW representative group or commission consisting of NKPA and CPVA PW, and are willing to work out the details of such an organization as soon as practicable after General Dodd's release.

Colson added that Dodd must be freed by noon and no later.63

With the exception of the word "more" in Item 3, Colson's reply was noncommittal and the Communists refused to accept it or release Dodd. Always opportunistic, they were determined to win more from the U.N. Command before they surrendered their trump card. The haggling began in the late morning and lasted until evening as the prisoners argued about the wording of Colson's answer.64

As the antagonists on Koje-do wrangled over the details, Ridgway and Van Fleet encountered increasing difficulty in finding out what was going on. When news of the four demands seeped back to UNC headquarters, Ridgway had attempted to forestall Colson's reply, but had been too late. He realized the propaganda value of an admission of the prisoners' charges, but Van Fleet had assured him that Colson's answer carried no implied acknowledgment of illegal or reprehensible acts.65 As the afternoon drew to a close and no report of Colson's negotiations arrived in Tokyo, Ridgway became impatient. Pointing out that incalculable damage might be done to the UNC cause if Colson accepted the prisoners' demands, he complained of the lack of information from Koje-do. "I have still been unable to get an accurate prompt record of action taken by your camp commander in response to these latest Communist demands. I am seriously handicapped thereby in the issuance of further instructions."66

Actually Van Fleet knew little more than Ridgway at this point. Colson had been so busy that even Yount was not completely abreast of all the developments. When the noon deadline passed without incident, Dodd phoned Colson and presented the prisoners' case. He argued that there had been incidents in the past when prisoners had been killed and Colson's answer simply denied everything. Most of the difficulties stemmed from semantics, Dodd admitted, but until these were cleared up, the Communists would not free him. With the prisoner leaders sitting beside, him, Dodd passed on their and his own suggestions for preparing Colson's reply in an acceptable form and then offered to write in the changes that the prisoners considered mandatory. Colson agreed and informed Yount in general terms of the prisoners' objections.67

After a second version failed to satisfy the Communists, Colson attempted to meet their demands clearly so that there would be no further excuse for delay:

1. With reference to your item 1 of that message, I do admit that there has been instances of bloodshed where many PW have been killed and wounded by UN Forces. I can assure in the future that PW can expect humane treatment in this camp according to the principles of International Law. I will do all within my power to eliminate further violence and bloodshed. If such incidents happen in the future, I will be responsible.

2. Reference your item 2 regarding voluntary repatriation of Korean Peoples Army and Chinese Peoples Volunteer Army PW, that is a matter which is being discussed at Panmunjom. I have no control or influence over the decisions at the peace conference.

3. Regarding your item 3 pertaining to forcible investigation (screening) , I can inform you that after General Dodd's release, unharmed, there will be no more forcible screening or any rearming of PW in this camp, nor will any attempt be made at nominal screening.

4. Reference your item 4, we approve the organization of a PW representative group or commission consisting of Korean Peoples Army and Chinese Peoples Volunteer Army, PW, according to the details agreed to by Gen Dodd and approved by me.

The release hour was advanced to 2000 since so much time had been consumed in translating and discussing the changes.68

By the time the final version had been translated and examined by the prisoners, it was evening and the Communists endeavored to add one last oriental touch to what Yount called the "comic opera." They wanted to hold Dodd overnight so that they might hold a little ceremony in the morning. In recognition of his services Dodd was to be decked with flowers and escorted to the gate. But Colson had had enough and would concede no more. He demanded that Dodd be brought out that night as agreed and the Communists decided that they could afford to give in now that they had won their main objectives. At 2130 Dodd walked out of Compound 76 and was immediately taken to a place where he could be kept incommunicado.69

The "comic opera" with all the overtones of a tragedy reached its climax with the release of Dodd, but the aftermath promised to be just as exciting. Before the repercussions of the incident are discussed, however, a brief analysis of the affair might be helpful.

There is little doubt that the conditions on Koje-do were clearly known by Ridgway and Van Fleet before the kidnapping took place. For several weeks UNC personnel had not been permitted to enter many of the compounds and the possibility of violence was no secret. Koje-do was like a chronic appendix; the Far East Command and Eighth Army knew it would have to undergo radical treatment sooner or later, but they preferred to postpone the operation until the situation became acute.

Since the prisoners had set up a definite plan to capture Dodd, they probably would have seized him eventually. His contacts with the prisoners laid him open to kidnapping and as long as they refused to come out of the compounds to talk to him, it meant that unless he used force to bring the prisoner leaders out, he had to go to them or break off relations with them. In view of his orders to complete the fingerprinting and rostering of the prisoners and the disinclination to employ violent means, Dodd had little choice. Better security procedures, locks on the gates, a screen of guards between Dodd and the prisoners during the talks, might have prevented the kidnapping, but Dodd was careless in this respect and placed too much confidence in the prisoners' sincerity and good faith.

Actually the seizure of Dodd in itself might have been relatively unimportant. It was only when the Communists skilfully used Dodd as a pawn and then backed his capture with the threat of a mass breakout that they were able to practice extortion in so bold a fashion. Despite the fact that there were over eleven thousand armed troops supported by tanks and other weapons and despite the instructions from Ridgway and Van Fleet to employ force if Dodd was not freed, the Communists carried off the honors. What had begun as a military problem to be solved by military means became a political problem settled on the prisoners' terms. The Communists had seized the initiative and never relinquished it. Using the menace of massive resistance as a club, they successfully blocked the use of force and played upon the desire of Colson to bring the affair to a bloodless conclusion.

During the last day of negotiations Dodd's role as intermediary became more vital. Given a new lease on life by the postponement of action, he labored zealously to help work out a formula that the prisoners would accept. Under these circumstances, the concessions that he urged upon Colson tended to favor the Communist position on the controversial items. The pressure of time and of translation added to confusion. It is evident that the Communists knew what they wanted and that Dodd and Colson were more interested in preventing casualties than they were in denying political and propaganda advantages to the enemy.

Unfortunately the hurried and continual negotiations cut down the flow of information to higher headquarters or the statements open to distortion or misinterpretation might have been caught in time and excised. As it turned out, Colson traded Dodd's life for a propaganda weapon that was far more valuable to the Communists than the lives of their prisoners of war.

It would not be fair to close without mentioning two matters that were bound up in the Dodd incident and in the events that followed. If force had been employed, there was the distinct possibility that reprisals might have been taken against the UNC prisoners under Communist control. And secondly, the attainment of Communist aims in these negotiations may very well have softened later resistance in the prison camps. While it is impossible to judge the importance of these probabilities, they should not be forgotten or overlooked.

Bitter Harvest

Although Van Fleet tended to discount the value of the Colson letter, Clark and his superiors in Washington were quite concerned. They realized the damaging implications that the Communists would be certain to utilize. Phrases like "I can assure in the future that PW can expect humane treatment" implied that the prisoners had not received humane treatment in the past. The promise that there would be "no more forcible screening or rearming of PW in this camp . . . " conveyed an entirely erroneous impression since there never had been any rearming of prisoners and forcible screening had been canceled.70

Since the press was becoming impatient for more information. Clark decided to publish a statement on the incident. He included both the prisoners' demands and Colson's reply. Dodd also met the press and issued a brief account of his capture and release.71 In general the response to the affair and the letter was unfavorable and at Panmunjom the Communist delegates made full use of the propaganda value of the episode to discomfort the UNC representatives.

At 2d Logistical Command headquarters, Yount established a board to investigate the matter and it found Dodd and Colson blameless. This did not satisfy Van Fleet, who felt that Dodd had not conducted himself properly nor had his advice to Colson been fitting under the circumstances. He recommended administrative action against Dodd and an administrative reprimand for Colson.72 Clark was even more severe; he proposed reduction in grade to colonel for both Dodd and Colson and an administrative reprimand to Yount for failing to catch several damaging phrases in Colson's statement.73 The Department of the Army approved Clark's action.

The quick and summary punishment of the key officers involved did not solve the problem of what to do about Colson's statement or the more basic question of how to clean up the longstanding conditions in the prison camps. Although the Washington leaders did not want to "repudiate" the letter, they told Clark to deny its validity on the grounds that it was obtained under duress and Colson had not had the authority to accept the false charges contained in the Communist demands.74 The first count was no doubt true but the second was certainly moot.

Denial was not enough for the press, and on 27 May Collins gave Clark permission to issue a concise and factual release. The Chief of Staff felt that the U.N. Command had always abided by the Geneva Convention and allowed the ICRC regular access to the camps. Clark's account, he went on, should stress this and emphasize that the incidents stemmed from the actions of the fanatical, die-hard Communists. In closing, the Far East commander should outline the corrective measures being taken.75

In the wake of Koje-do came a series of actions. The stiffening attitude of the UNC revealed itself first at Prisoner of War Enclosure Number 10 at Pusan for hospital cases. Among the patients and attached work details, 3,500 in Compounds 1, 2, and 3 had not been screened and segregated. Hoping to forestall concerted action, the camp commander, Lt. Col. John Bostic, informed the prisoners on 11 May that food and water would be available only at the new quarters prepared for them. He planned to screen and segregate the nonpatients first as they moved to the new compounds and then take care of the sick. Although he had two battalions of infantry in positions around the three compounds, only Compound 3 made any attempt to negotiate conditions under which they would be screened and moved. Bostic refused to treat with the leaders of Compound 3; the other compounds simply remained indifferent to his order.76

After a deceptively quiet night, the prisoners became restive. Signs were painted, flags waved, demonstrations mounted, and patriotic songs sung as feelings ran high. Infantrymen of the 15th Regiment surrounded the compounds with fixed bayonets and a couple of tanks were wheeled into positions, but no attempt was made to start the screening.77

Despite complaints from the prisoners, they made no effort to comply with Bostic's instructions. Compound 3 set up sandbags during the night of 12 May but no further violence occurred. On the next day, loudspeakers started to hammer home the UNC orders over and over again, yet the prisoners laughed at offers of hot food and cigarettes available to them in the new compounds.78

A few stray shots were fired on the 14th and the prisoners hurled rocks at the guards, but the deadlock continued. To break the impasse, Van Fleet permitted several ICRC representatives to interview the prisoners. Compound 1 requested the first conference with the Red Cross men and then the other compounds followed suit. The prisoners became quieter after the ICRC talks, but they were not ready to obey Bostic's orders. On 15 May Yount won Van Fleet's approval to put the emphasis on control rather than screening, with the prisoners not screened to remain unrostered until a settlement was reached at Panmunjom. Armed with this authority and with ICRC help, Bostic reached an agreement with the leaders of Compound 1 on 17 May. There was no screening and the prisoners moved without incident to their new compound.79

Hope that the other two compounds would follow the example of Compound 1 proved forlorn. On 19 May, Van Fleet approved the use of force to clear the recalcitrant compounds. After a brief announcement the following morning warning the prisoners that this was their last chance to obey, infantry teams entered Compound 3 and advanced against mounting resistance. Armed with stones, flails, sharpened tent poles, steel pipes, and knives, the defiant prisoners screamed insults and challenges. The infantry maintained excellent discipline, using tear gas and concussion grenades to break up the prisoners' opposition. Herding the prisoners into a corner, the U.N. troops forced them into their new compound. Only one prisoner was killed and twenty-nine were wounded as against one U.S. injury. The example of Compound 3 evidently was borne home to Compound 2, for on 21 May they put up no resistance as the infantrymen moved them into new quarters without casualties to either side.80

Whether the prisoners were screened or not became secondary after the Dodd incident. Van Fleet was most anxious to regain control over all the compounds and he had his staff examine the situation carefully in mid-May. They submitted three alternatives on 16 May: 1. Remove all prisoners from Korea; 2. Disperse the prisoners within Korea; and 3. Combine 1 and 2 by removing some prisoners and dispersing the rest. If all of the POW's were transferred out of the country, the Eighth Army commander would be free to concentrate on his primary mission and be relieved of a rear area security problem. Under the third alternative, at least some of the prisoners would be shifted and the Eighth Army responsibility lessened. Van Fleet preferred the first, but found the third more desirable than the retention of all of the prisoners in Korea. Dispersal within Korea would ensure better control, to be sure, but it would entail more logistic support and more administrative and security personnel. But Clark did not accept the movement of any of the prisoners out of Korea and he instructed Van Fleet to go ahead with his dispersal plan as quickly as possible. He was willing to send the 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team to Van Fleet to aid in the operation. Additional tank support would have to be supplied by Eighth Army if it were required.81

Besides the reinforcement of the Koje-do forces, Van Fleet intended to construct barricades and roadblocks at strategic points until he was prepared to deconcentrate the prisoners. The new enclosures would be located on Koje-do, Cheju-do, and on the mainland and he estimated that twenty-two enclosures, each holding 4,000 prisoners and at least one-half mile apart, would be sufficient. Compounds would be limited to 500 men apiece with double fencing and concertina wire between compounds. When the new camps were finished, Van Fleet was going to try to use the prisoners' representatives to induce them to move voluntarily. But if resistance developed, as he expected it would, food and water would be withheld and the prisoners would receive these only at the new compounds. As a last resort, he would employ force. Both Clark and his superiors agreed that although the plan might incur unfavorable publicity and had to be handled carefully, the Communist control on Koje-do had to be broken.82

Van Fleet accepted the recommendations that ICRC assistance be utilized as much as possible and that other UNC contingents be added to the forces on Koje-do. He had the Netherlands Battalion already on the island and he would send a U.K. company, a Canadian Company, and a Greek company to provide a U.N. flavor. As for the press, normal coverage facilities would be provided.83

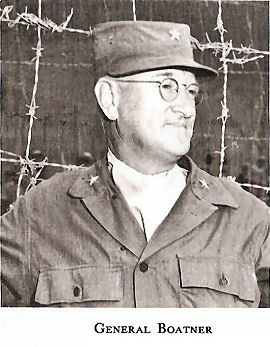

To supervise the difficult task of moving the prisoners, Van Fleet appointed Brig. Gen. Haydon L. Boatner, assistant division commander of the 2d Division, as the new commander of Koje-do.84 Using infantrymen as well as engineers, Boatner pushed the construction of the smaller, stronger enclosures by working his troops in two twelve-hour shifts. He also moved over 6,000 civilians away from the camp and off the island.85

By early June Boatner was prepared to test his plan for securing control of the Communist compounds. Despite- repeated orders to remove the Communist flags that were being boldy flown in Compounds 85, 96, and 60, the prisoners ignored Boatner's commands. On 4 June, infantrymen from the 38th Regiment supported by two tanks moved quickly into Compound 85. While the tanks smashed down the flagpoles, the troops tore down signs, burnt the Communist banners, and rescued ten bound prisoners. Half an hour later they repeated their success at Compound 96 and brought out seventy-five prisoners who wished to be freed of Communist domination. The only enemy flags still aloft were in Compound 60 and the infantry did not need the tanks for this job. Using tear gas, they went in and chopped down the poles. |

|

Not a single casualty was suffered by either side during these quick strikes.86 Although the prisoners restored the flagpoles the following day, the experience gained in the exercise seemed helpful.

Satisfied by this test run, Boatner decided to tackle the big task next. On the morning of 10 June, he ordered Col. Lee Hak Koo to assemble the prisoners of Compound 76 in groups of 150 in the center of the compound and to be prepared to move them out. Instead the prisoners brought forth their knives, spears, and tent poles and took their positions in trenches, ready to resist. Crack paratroopers of the 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team wasted little time as they advanced without firing a shot. Employing concussion grenades, tear gas, bayonets, and fists, they drove or dragged the prisoners out of the trenches. As a half-dozen Patton tanks rolled in and trained their guns on the last 300 prisoners still fighting, resistance collapsed. Colonel Lee was captured and dragged by the seat of his pants out of the compound. The other prisoners were hustled into trucks, transported to the new compounds, fingerprinted, and given new clothing. During the two-and-a-half-hour battle, 31 prisoners were killed, many by the Communists themselves, and 139 were wounded. One U.S. soldier was speared to death and 14 were injured.87 After Compound 76 had been cleared, a tally of weapons showed 3,000 spears, 4,500 knives, 1,000 gasoline grenades, plus an undetermined number of clubs, hatchets, barbed wire flails, and hammers. These weapons had been fashoned out of scrap materials and metaltipped tent poles by the prisoners.88

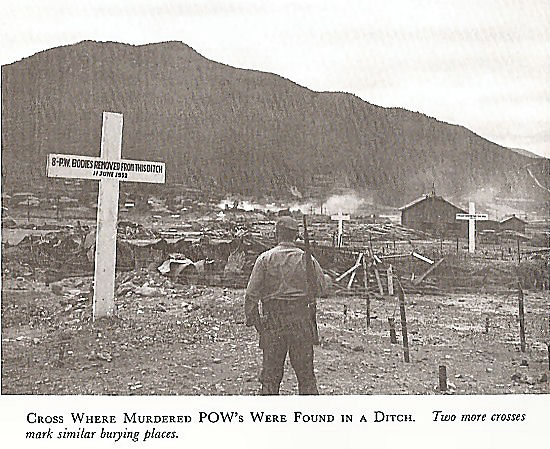

The aftermath proved how quickly the lesson was learned. After leaders of Compounds 78 and 77 had witnessed the fight, they swiftly agreed to move whereever Boatner wanted them to. In Compound 77 the bodies of sixteen murdered men were found. The show of force was effective in eliminating the core of Communist defiance and paved the way for the relatively uneventful transfer of the other compounds on Koje-do to their new stockades during the rest of June.

With the dispersal plan successfully completed, Clark decided to remove the POW problem from Eighth Army jurisdiction. On 10 July the Korean Communications Zone was established under the Far East Command and took over responsibility for rear area activities from the Eighth Army.89 One of the lessons that had to be relearned during the Koje-do affair was that an army commander should not be burdened with the administration of his communications zone, since the distraction could not fail to detract from his efficiency in carrying out his primary mission- to fight the enemy.

There were other lessons that were brought home during this period. In most cases, after a prisoner was captured, he might attempt to escape and this was about as far as he would go. With the Communists a new element of experience was added. The Communist prisoner's service did not end with his capture but frequently became more important. In the prison camp his responsibilities shifted from the military to politico-military duties. Easy to organize and well-disciplined, the loyal Communist prisoners required strict control or they would exploit their position for propaganda purposes. Death or injury was readily accepted if the ends were worthwhile and soft treatment merely made them more insolent and disobedient. Only force and strength were respected, for these they recognized and understood. As for the administration of the Communist prison camps, the necessity for high quality personnel at all levels was plain. Unless the leadership and security forces were well briefed politically and alert, the Communist would miss no opportunity to cause trouble. At Koje-do the lack of information of what was going on inside the compounds pointed up another deficiency. Trained counterintelligence agents had to be planted inside to keep the camp commander advised on the plans and activities of the prisoners and to prevent surprises like the Dodd capture from happening.

In assessing the effects of the Koje-do incidents, it is difficult to escape the conclusion that they seriously weakened the international support that the UNC Command had been getting on its screening program and on voluntary repatriation. In Great Britain, questions were raised in Parliament implying that the screening in April had been improperly or ineffectively carried out. Japanese press opinion reflected a growing suspicion that the US authorities had lost control of the screening process and permitted ROK pressure to be exerted directly or indirectly against repatriation. As General Jenkins, Army G-3, pointed out to General Collins early in June: "The cumulative effect of sentiment such as that reflected above may tend to obscure the UNC principle of no forcible repatriation, and appear to make the armistice hinge on the questionable results of a discredited screening operation."90

The presence of International Committee of the Red Cross representatives during the clean-up activities at Pusan and Koje-do did little to enhance the reputation of the UNC prisoner of war policies. Although the ICRC could offer little constructive advice on how the UNC could regain control and admitted that the prisoners were committing many illegal acts, they protested vigorously against the tactics of the UNC. Violence, withholding food and water- even if these were available elsewhere- and the use of force on hospital patients were heavily scored and the reports that the ICRC submitted to Geneva were bound to evoke an unfavorable reaction in many quarters.91

Despite the fact that focus shifted from Koje-do as the dispersal program brought the Communist prisoners under tighter controls, the mushroom cloud of doubt and suspicion that hovered over the Koje-do episode could not help but make the task of the UNC delegates at Panmunjom more complex.

Notes

1 Hq 2d Logistical Comd, Comd Rpt, May 52, p. 2.

2 Samuel M. Myers and William E. Bradbury, The Political Behavior of Korean and Chinese Prisoners of War in the Korean Conflict: A Historical Analysis, Tech Rpt 50 (Human Resources Research Office, George Washington University, 1958) , p. 65.

3 Interv with Col Dame, 20 Oct 59. In OCMH.

4 Hq 2d Logistical Comd, Comd Rpt, May 52, pp. 2-3.

5 (1) Hq 2d Logistical Comd, Comd Rpt, May 52, Vol. II, tab F. (2) Interv with Col Dame, 20 Oct 59. (3) Interv with Col Maurice J. Fitzgerald, 2 Dec 59. In OCMH.

6 See Chapter VII, above.

7 DA Pamphlet 20-150, October 1950, Geneva Convention of 12 August 1949 for the Protection of War Victims.

8 Hq UNC/FEC MIS, The Communist War in POW Camps, 28 January 1958, pp. 6-8. This account is based upon seized enemy documents, interviews with prisoners and captured enemy agents, and intelligence reports.

9 Ibid., pp. 26-28.

10 Hq 2d Logistical Comd, Comd Rpt, May 52, vol. II, tab E.

11 Msg, C 50603, CINCUNC to DA, 21 Jun 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jun 52, CinC and CofS, Supporting Docs, tab 83.

12 (1) Ltr, Col Albert C. Morgan to CG Eighth Army, 18 Sep 51, sub: Security for POW's in Hq 2d Logistical Comd, Coma Rpt, May 52, vol. II, tab A-10. (2) Hq 2d Logistical Comd, Comd Rpt, May 52, vol. II, tab H.

13 Interv with Col Fitzgerald, 2 Dec 59. In OCMH.

14 Hq 2d Logistical Comd, Comd Rpt, May 52, vol. II, tab 3, pp. 8-9; tab G, Chart 3.

15 Msg, CX 69250, Clark to CofS, 28 May 52, DA-IN 144360.

16 Gen Yount's Statement to Gen Clark, no date, in FEC Gen Admin Files, Gen Clark's File.

17 See Chapter VII, above.

18 The 27th Regiment of the 25th Infantry Division was called the Wolfhounds and had been moved to Koje-do during January to bolster the security forces.

19 (1) Msg, G 71528, Van Fleet to CINCUNC, 19 Feb 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Feb 52, an. 1, incl 11. (2) Msg, G 71542, Van Fleet to CINCUNC, 19 Feb 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Feb 52, an. 1, incl 12. (3) Hq 2d Logistical Comd, Comd Rpt, May 52, p. 7.

20 (1) Msg, G 4615 TAC, Van Fleet to CINCFE, 20 Feb 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, an. 1, incl 14. (2) Msg, DA go1675, CSUSA to CINCFE, 20 Feb 52. (3) Msg, DA 901709, CSUSA to CINCFE, 22 Feb 52.

21 UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Mar 52, an. 1.

22 Memo, Maj Gen Bryan L. Milburn, G-1 FEC, for Gen Van Fleet, 29 Feb 52, sub: Planning for POW's . . . , in FEC Gen Admin Files, CofS, 1952 Corresp.

23 (1) Msg, CX 65213, CINCUNC to JCS, 14 Mar 52, DA-IN 115842. (2) Msg, CX 65281, CINCUNC to JCS, 14 Mar 52, DA-IN 115919

24 See Chapter VIII, above.

25 Msg, GX 5410 TAC, Van Fleet to Ridgway, 13 Apr 52, in FEC Gen Admin Files, CofS, Personal Msg File, 1949-52.

26 Hq 2d Logistical Comd, Comd Rpt, May 52, vol. II, pp. 13ff.

27 Msg, GX 5410 TAC, Van Fleet to Ridgway, 13 Apr 52, in FEC Gen Admin Files, CofS, Personal Msg File, 1949-52.

28 Msg, GX 5637 TAC, Van Fleet to Ridgway, 28 Apr 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 52, an. 1, incl 73.

29 Msg, CX 6750, CINCFE to JCS, 29 Apr 52, DA-IN 133133.

30 (1) Msg, JCS 907528, JCS to CINCFE, 29 Apr 52. (2) Msg, JCS 908093, JCS to CINCFE, 7 May 52.

31 Msg, CX 67888, Ridgway to CG Eighth Army, 5 May 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, May 52, an. 1, incl 56.

32 Msg, GX 5746 TAC, Van Fleet to Ridgway, 5 May 52, in FEC Gen Admin Files, CofS, Personal Msg File, 1949-52.

33 Extract, Visit to Eighth Army Headquarters with Col Chaplin, 8 May 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, May 52, an. 1, incl 58.

34 Hq 2d Logistical Comd, Comd Rpt, May 52, pp. 12ff. The compound leaders were afraid that the UNC would transfer them to another area if they left the safety of their own compounds. This made them reluctant to go to Dodd's office and if Dodd wanted to talk to them, he had to go to the compound.

35 Statement of Col Raven, 12 May 52, before a Board of Officers at Koje-do, in FEC Gen Admin Files, Proceedings of Board of Officers.

36 (1) Ibid. (2) Statement of Gen Dodd, 14 May 52, in FEC Gen Admin Files, Proceedings of Board of Officers.

37 Exhibit O4(1), in FEC Gen Admin Files, Exhibits.

38 Exhibit N4(1), in FEC Gen Admin Files, Exhibits.

39 Ibid.

40 Hq 2d Logistical Comd, Comd Rpt, May 52, p. 21.

41 Ibid., pp. 22-23.

42 Exhibits M4(2) and M4(4), in FEC Gen Admin Files, Exhibits.

43 Hq 2d Logistical Comd, Comd Rpt, May 52, pp. 23-24.

44 Ibid, pp. 24-25.

45 Interv, author with Gen Colson, 4 Oct 59. In OCMH.

46 Msg, GX 5775 TAC, CG EUSAK to CG 2d Logistical Comd, 8 May 52, in FEC Gen Admin Files, Exhibits.

47 (1) Ltr, Colson to POW Compound 76, 9 May 52, Exhibit E4(6) (2) Ltrs, Lee to Colson, 9 May 52, Exhibits E4(2) and E4(4). Both in FEC Gen Admin Files, Exhibits.

48 Teleconf, Mood and Yount, 9 May 52, in Rd Logistical Comd, Telecon File, vol. I, 7 May-15 May 52, tab 20.

49 Teleconf, Colson and Yount, 9 May 52, in 2d Logistical Comd, Telecon File, vol. I, 7 May 52, tab 28.

50 Teleconf, Gen Dodd and Col Alvin T. Bowers, G-2, 2d Logistical Comd, 9 May 52, in 2d Logistical Comd, Telecon File, vol. I, 7 May-15 May 52, Tab 34.

51 Teleconvs, Colson and Dodd, 9 May 52, in 2d Logistical Comd, Telecon File, vol. 1, 7 May-15 May 52, tabs 38 and 39.

52 Ibid.

53 Ltr of Instr, Colson to Staff, 8137th Army Unit et al., 9 May 52, in FEC Gen Admin Files, Proceedings of Board of Officers.

54 General Clark served as U.S. commander in Italy during World War II, then became American High Commissioner for Austria after the war. He was Commanding General, Army Field Forces, prior to his assignment as CINCFE.

55 CG Conf at 091340 May at Koje-do, tab 55, in 2d Logistical Comd, Telecon File, vol. I, 7 May-15 May 52.

56 (1) Teleconvs, Yount, Bowers and Colson, Yount and Mood, g May 52, in 2d Logistical Comd, Telecon ,File, vol. I, 7 May-i5 May 52, tabs 48 and 49. (2) 2d Logistical Comd, Comd Rpt, May 52, p. 35.

57 Interv, author with Colson, 4 Oct 59. In OCMH.

58 Teleconv, Yount and Colson, 9 May 52, in 2d Logistical Comd, Telecom File, vol- I, 7 May-15 May 52, tab 57.

59 Msg No. 2, Lee to CG Koje-do PW Camp, 10 May 52, Exhibit E4(8), in FEC Gen Admin Files, Exhibits. 60 Interv, author with Colson, 4 Oct 59- In OCMH.

61 Teleconvs, Yount and Colson, tab 60, Yount and Mood, tab 61, to May 52, in 2d Logistical Comd, Telecon File, vol. I, 7 May-15 May 52.

62 See Teleconv, Bowers and Murray, to May 52, in 2d Logistical Comd, Telecon File, vol. I, 7 May- May 52, tab 85. It was unfortunate that a firstclass translator was not called in until too late to help in these intricate negotiations, but it should be remembered that the decision to negotiate did not come until the morning of the 10th.

63 Ltr, Colson to Compound 76, to May 52, in 2d Logistical Comd, Telecon File, vol. I, 7 May-15 May 52, tab 55.

64 Msgs Nos. 4 and 5, Lee to Colson, 10 May 52, Exhibits E4(6) and E4(12), in FEC Gen Admin Files, Exhibits.

65 Teleconv, Hickey and Van Fleet, 10 May 52, in FEC, Gen Admire Files, Gen Clark's File.

66 Msg, C 68268, Ridgway to Van Fleet, to May 52, in FEC Gen Admire Files, Gen Clark's File.

67 (1) Testimony of Colson before Board of Officers, 12 May 52, in FEC Gen Admire Files, Proceedings of Board of Officers. (2) Teleconv, Yount and Colson, 10 May 52, in 2d Logistical Comd, Telecon File, vol. I, 7 May-15 May 52, tab 74.

68 (1) Testimony of Colson before Board of Officers, 12 May 52, in FEC Gen Admin Files, Proceedings of Board of Officers. (2) Transcript of Conference in Office of DCofS FEC, 18 May 52, in FEC Gen Admin Files, Gen Clark's File. Colson had confused his second and third letters in his earlier testimony. The version quoted above was the third and final letter accepted by the Communists.

69 (1) Teleconvs, Craig and Yount, 10 May 52, tab 81 and tab 97; Yount and Mood, 10 May 52, tab 103. All in 2d Logistical Comd, Telecon File, vol. I, 7 May-15 May 52.

70 (1) FEC Memo for Rcd, Teleconv, Clark and Van Fleet, 12 May 52. (2) DA-CINCFE Teleconf, 13 May 52. Both in FEC Gen Admin Files, Gen Clark's File.

71 Mark W. Clark, From the Danube to the Yalu (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1954) , pp. 45-46 Colson later stated that he never understood why Clark published his letter and aggravated the situation. See interview of the author with General Colson, 4 October 1959. In OCMH.

72 See: (1) Rpt of Board of Officers, i2-ig May 52; (2) Memo, Van Fleet for CINCFE, 16 May 52, sub: Proceedings of Board of Officers. Both in FEC Gen Admin Files, Proceedings of Board of Officers.

73 Lt.r, Clark to TAG, 2o May 52, sub: Proceedings of Board of Officers, in FEC Gen Admin Files, Gen Clark's File.

74 (1) Msg, JCS 908789, JCS to CINCFE, 15 May 52. (2) Clark, From the Danube to the Yalu, p. 46.

75 Msg, DA 909857, CofS to CINCFE, 27 May 52.

76 Hq 2d Logistical Comd, Comd Rpt, May 52, pp. 56-57.

77 Teleconv, Bostic and Yount, 12 May 52, in 2d Logistical Comd, Telecon File, vol. I, 7 May-15 May 52, Tab 172.

78 Teleconvs, Bostic and Murray, SGS; Bostic and Col Morton P. Brooks, 2d Logistical Comd, Bostic and Murray; 13 May 52. All in 2d Logistical Comd, Telecon File, vol. I, 7 May-15 May 52, tabs 179, 181, 191.

79 Ltr, Craig to CO 93d Mil Police Bn, 17 May 52, sub: Segregation of Personnel, in 2d Logistical Comd, Comd Rpt, vol. II, May 52, tab 2.

80 (1) Memo for Rcd, by Col Craig, 21 May 52, sub: Opns at No. 10, in Rd Logistical Comd, Comd Rpt, vol. II, May 52. (2) Hq Rd Logistical Comd, Comd Rpt, May 52, pp. 60-61.

81 (1) Msg, C 68728, Clark to CG Eighth Army, 20 May 52, in FEC Prisoners of War. (2) Hq Rd Logistical Comd, Comd Rpt, May 52, pp. 62-64.

82 (1) Msg, CX 68852, Clark to JCS, 17 May 52, DA-IN 140107. (2) Msg, JCS 909231, JCS to CINCFE, 20 May 52 .

83 Msg, G 6001 TAC, CG Eighth Army to CINCFE, 21 May 52, in FEC Prisoners of War.

84 Msg, G 5849 TAC, Van Fleet to Clark, 13 May 52, in FEC Gen Admin Files, Gen Clark's File.

85 Hq 2d Logistical Comd, Comd Rpt, May 52, p. 66.

86 Teleconf, Lt Hall and Maj John E. Murray, 4 Jun 52, in 2d Logistical Comd, Comd Rpt, Jun 52, tab 1.

87 Hq 2d Logistical Comd; Comd Rpt, Jun 52, vol. I, tab 5.

88 UNC Rpt No. 47, 1-15 Jun 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jun 52, CinC and CofS, Supporting Docs, tab 76.

89 UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 52.

90 Memo, DA 145230, Jenkins for CofS, g Jun 52, sub: International Concern over UNC Prisoners Screening Opns, in G-3 091 Korea, 8/33.