Date: Thu, 11 Nov 1999 13:35:10 -0500 FOR POWs, KOREA WAS NOT AMERICA'S "FORGOTTEN WAR"

Scripps Howard News Service

By MICHAEL HEDGES

Scripps Howard News Service

The Korean War is often described as America's "forgotten war," but the intense emotion with which many former prisoners of war remember the misery, terror and despair they suffered in that conflict almost a half-century ago belies that description.

Wilbert "Shorty" Estabrook of Murietta, Calif., hasn't forgotten the weight of the bodies that he and other POWs were forced to carry during a North Korean death march in which scores of American prisoners died.

And Gene Bleuer of Rock Island, Ill., has a vivid recollection of Chinese guards lining up groups of POWs and staging mock executions with unloaded guns,,then, about once a week, loading the guns and killing several prisoners.

Nor have those whose family members vanished during the war, 8,200 Americans still listed as missing in action in Korea, forgotten.

John Zimmerlee, of Hapeville, Ga., hopes the government will eventually release information providing clues to the fate of his father, John Henry Zimmerlee, whose B-26 was lost over North Korea in March 1952.

And Vincent Krepps of Towson, Md., searches the Internet for details about the death in captivity of his twin brother Richard.

But apart from their circle of friends, family and wartime companions, many Korean-era POWs and MIA relatives feel they were forgotten, or, more accurately, ignored, after the unpopular, inconclusive war ended.

"Korean POWs as a whole are more bitter than the Vietnam group," said Alan Marsh, cultural resources specialist at the government's National Prisoner of War Museum in Andersonville, Ga. "A big part of that is that they came back and found that people just wanted to forget the war."

Marsh, who has participated in a project to record hundreds of oral histories of American POWs, going back to World War I, said, "It is not that they have to be known as heroes. They just want people to know what they went through."

What they went through was horrific.

The official death rate of the 7,140 Americans captured in the Korean War is roughly 40 percent. More than 2,700 POWs are known to have died in captivity. That mortality rate is higher than for any group this century, except perhaps Americans held by the Japanese during World War II.

Torture and attempted brainwashing was common among POWs in North Korea.. Even deadlier was neglect of their dietary and medical needs.

And when they were released, the POWs were not embraced by a grateful nation.

Estabrook, who had survived more than 37 months in captivity, enduring a brutal death march, witnessing executions and seeing well over half those captured with him die _ recalled that the indifferent treatment of POWs began soon after their release in 1953.

They were segregated behind a rope barrier from other soldiers on a troop ship returning to San Francisco, said Estabrook, 69. "The attitude of the guys who weren't prisoner was, 'While you guys were sunning yourself up on the Yalu River, we did the heavy fighting,"' he said. After one of the former POWs started "a small riot," the rope barrier came down, Estabrook said.

But the sense of isolation and alienation persisted. "There was this 'Communist thing' hanging over us," Estabrook said. "A lot of people were talking about collaborating with the enemy and so on. Mostly, people just didn't seem to care."

"The Korean war POW experience, especially early in the war, was a slaughterhouse," said Laurence Jolidon, whose book, "Last Seen Alive," explored the issue of American POWs left behind in Korea after the war. "The cruelty was astounding. If you survived a death march to get to a camp, there was nothing there _ no food, no medicine, no clothing."

Given the conditions, Jolidon said, much of the criticism of Korean POWs springs from "ignorance." He said, "Most of them did the best they could to serve honorably and survive."

Of the 7,140 American POWs, 21 agreed to stay behind in North Korea or China. Others signed statements falsely confessing to war crimes such as using germ warfare on the Chinese. These statements, according to experts, were usually elicited by various forms of physical and psychological abuse, ranging from beatings and threats of executions to denial of sleep, food and heat.

"In those days people didn't pay any attention to whether it was done under duress," Estabrook said.

Korean POW experts noted that, as a group, those taken captive in the war were much younger and, in most cases, less well trained than Vietnam War POWs. The North Koreans and, later, Chinese often segregated officers from enlisted men, a tactic that broke down cohesion and discipline among the captives.

One of the enduring mysteries of the war that still haunts many of the ex-POWs as well as the families of the missing revolves around whether some POWs were left behind after the war to be taken involuntarily to China or Russia.

Bleuer, 70, said that when he and 13 companions were released by the Chinese in the spring of 1951, scores of men in his outfit, B Company, 5th Regimental Combat Team, attached to the 24th Infantry, were still in Chinese hands and in relatively good health.

"No one else (from his unit) ever got out, as far as I know," he said. "They have not been heard of again."

Retired Sgt. 1st Class George Matta, a veteran of three wars, told his son George Jr. about POWs being loaded in Russian trucks which he believed took them against their will to the USSR or China. "He definitely knew of people who were alive and in good shape when he was released who never came out," Matta Jr. said.

"My best estimate is that at the end of hostilities, at least 2,000 of the 8,200 MIAs were still alive and in enemy hands," said Jolidon, the author. "Their fate we don't know."

Larry Greer, a spokesman for the Pentagon's Department of Prisoner of War and Missing Personnel Office, said, "What we have are tantalizing reports (of POWs still alive). But so far these reports are not supported by tangible evidence. It doesn't mean they are not true ... but we cannot corroborate with evidence that there were Americans alive in Russia after the war."

Zimmerlee, who was not quite 3 years old in March 1952 when his father disappeared while on a reconnaissance mission, is reconciled to his father's death, though "I always had the hope" of a miraculous return.

But he isn't satisfied with the government's insistence on still holding many records about the war secret.

"We know it is going to be embarrassing when the records are opened. Some of the decisions made by our leaders were asinine," he said. "But it is time to release everything they have. Get it over with."

Many Korean War-era veterans are increasingly turning to the Internet in an effort to answer questions that have dogged them for nearly half a century.

One such site is the Korean War Project, run by Hal and Ted Barker of Dallas, brothers whose father Edward was awarded the Silver Star as a Marine Corps helicopter pilot in Korea. The Web site (www.Koreanwar.org ) serves as a meeting place for Korean-era POWs, relatives of MIAs and others.

Ted Barker said the project was designed to give Korean vets a place to feel at home. "The fellows were shunned after the war, and many of them have been very quiet about their experiences ever since," he said.

He said that since the opening of the Korean War Memorial in Washington, D.C., in 1995, "more and more of the guys from Korea have been coming out, looking for their buddies."

Among those who made a connection with the past through the Internet was Vincent Krepps of Towson, Md. The editor of a newsletter for former Korean POWs called "The Graybeards," Krepps has written movingly of his experiences as a 19-year-old in Korea in 1950.

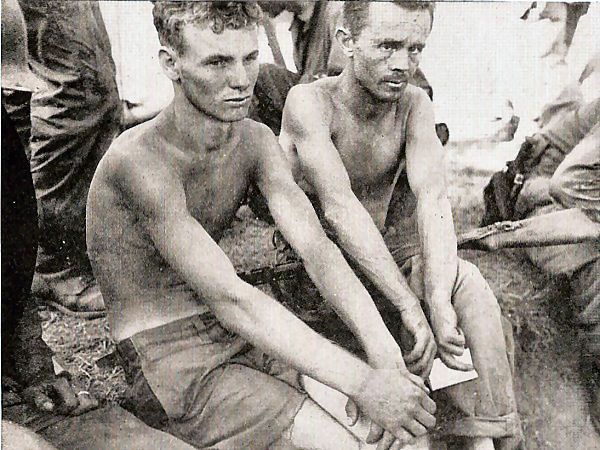

Now 67, Krepps won a Silver Star for his actions during fighting near the Naktong River. But shortly after that, his twin brother Richard, who had joined the Army with him, was listed as missing, presumably a prisoner of the Chinese. For months, the family agonized over Richard's fate. Then, in early 1951, a relative spotted him in a photo of POWs that the Chinese released as propaganda.

When the Korean POWs were released, however, Richard Krepps was not among them. All the family ever heard from the U.S. government was a note that the Chinese had "unofficially" listed him as having died in captivity in June 1951.

In 1998, the daughter of a Nevada man, Ronald Lovejoy, came across Krepps' Internet postings searching for news of his brother. Lovejoy had been with Richard Krepps as he wasted away and died and had held on to a photo from his wallet that he gave to Vincent during an emotional meeting in July.

Questions were answered, but the pain remained. "I think of my brother every day," Krepps has written. "Sometimes late at night Richard visits me in a dream, the two of us playing baseball as kids, or driving together with the wind whipping our hair, or sitting on sandbags in Korea, talking long into the night."

(Michael Hedges is a reporter for Scripps Howard News Service) AP-NY-11-04-99 1749EST

KWP Ed Note: Ask your paper to run this story. It may be obtained from Scripps Howard News Service Bureau