Killing of enemy who were wounded and helpless was done by all sides in the Korean War, and in all wars. In the desperation of combat, particularly when there is no provision for caring for wounded and no troops to spare to guard them, this sometimes is a practical necessity, however horrible the idea.

On the east side of the Chosin Reservoir, CCF 80th Division troops killed about 300 helpless men from the US 31st Regimental Combat Team. Almost all the men were wounded, who had been packed like sardines into trucks or trailers. Abandoned by 3-31, the rear guard during the RCT's precipitous dash for safety with the Marines at Hagaru-ri, the wounded were trapped at a fire block. They were mostly killed by thermite grenades, thrown into the halted vehicles. A hideous death.

Hundreds of other 31RCT wounded, left behind because of limited space in the trucks, presumably met a similar fate.

The CCF didn't take the wounded American soldiers prisoner, and then murder them. They were caught up in an assault, were ill-equipped to care for hundreds of wounded prisoners, were facing possible counter-attack by our formidable 1st Marine Division, and just killed the prisoners out of hand, during battle. The Marines also killed many CCF soldiers who were wounded, or dying from the terrible cold, during their fight-out from Chosin. To most soldiers, the difference between killing during the peril of combat and murder when safe from retribution, is enormous and unforgiveable.

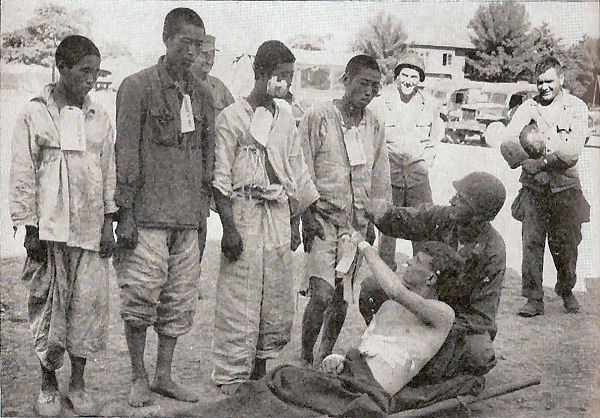

But North Korea seemed to see no difference. The NK did murder hundreds of American POWs, as well as tens of thousands of captured ROKs and helpless South Korean civilians, as a matter of policy. Frequently prisoners were first horribly mutilated, and even set on fire, while they were still alive. For the Americans, one of the worst was the slaughter of almost 100 American prisoners north of Pyongyang.

Over 53,000 ROK and UN soldiers were MIA, including over 8,000 Americans. Because of the brutal history of the North Korean army, one assumes the majority of the American soldiers were murdered after they had surrendered, or been found wounded. The rest probably died without record during imprisonment in the terrible conditions of Chinese POW camps.

The following account of NK murders of POWs early in the Pusan Perimeter battles is not conjecture or unproven accusation. We found and buried tens of thousands of civilians and UN servicemen who had been captured and bound, and then shot. First are shown photos and a contemporary Associated Press account, followed by a historical story in the Boston Globe

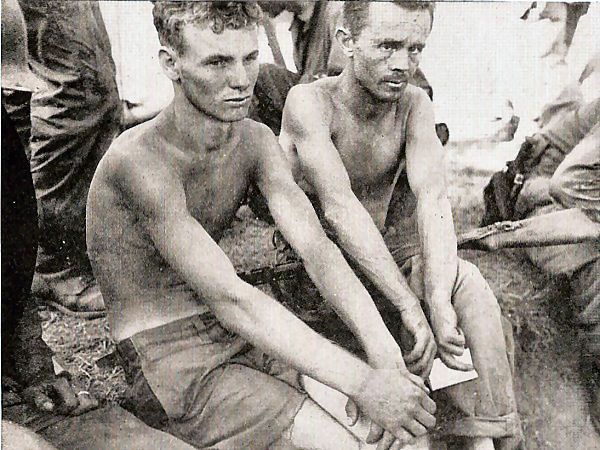

This is one of the few accounts of willful murders by the NK, from a survivor.

Rediscovering Pvt. Ryan Two US veterans recall forgotten massacre during Korean War

By Indira A.R. Lakshmanan, Globe Staff , 06/25/99

AEGWAN, South Korea - Forty-nine years ago, Private Frederick M. Ryan and 41 other American prisoners of war were gunned down on a Korean hillside, their hands tied behind their backs, and left for dead.

AEGWAN, South Korea - Forty-nine years ago, Private Frederick M. Ryan and 41 other American prisoners of war were gunned down on a Korean hillside, their hands tied behind their backs, and left for dead. A priest with the American unit that found the men kissed the wounded Ryan's forehead, administered last rites and draped a cross and a Purple Heart around his neck. But even though Ryan's side had been shattered by five bullets, he was one of five soldiers who miraculously survived the Aug. 17, 1950 massacre, their bodies shielded by those of their dead buddies.

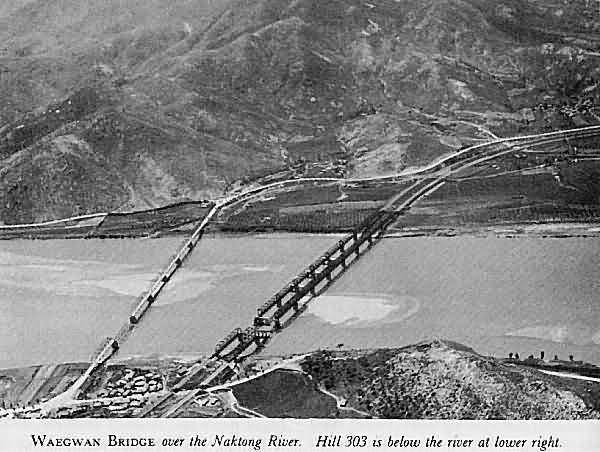

Ryan has returned to Hill 303 to find the massacre site and to say goodbye to the ghosts of the past. Today, on the 49th anniversary of the outbreak of the Korean War, Ryan and his fellow soldiers from a mortar platoon of the Army's 1st Cavalry Division are being recognized for their sacrifice, half a century late - thanks to an amateur military historian from New Hampshire.

''I've got to say goodbye to my friends. Their bodies might not be there, but their spirits are,'' said Ryan, 67, a retired railway conductor, mechanic, and gas station attendant from Cincinnati. ''If I could, I'd bring them back in a minute, but they died that day cussing out the other side ... and I know they'd die again just as they did for peace in this country.''

The 1950-53 Korean conflict is often called the ''forgotten war,'' and the massacre of American POWs at Hill 303 is one of many largely forgotten incidents from the chaotic early months when communist troops pushed South Korean and United Nations forces into a 100-mile-by-50-mile tip of the peninsula.

There was never a full accounting of what happened, nor a recognition of all the POWs. All these decades, the five survivors themselves did not know how many had made it out alive.

Enter Army Captain David Kangas of Greenville, N.H., a graduate of Fitchburg State College, who heard about the mass execution in 1985 when he was posted at Camp Carroll near Hill 303. Kangas asked around the base, and then at the Korean War Museum in town, and found that no one knew anything about it. The few historical accounts were sketchy.

He began a ''needle-in-a-haystack'' search through historical accounts, contemporary news reports, and the National Archives, hoping to find clues. The massacre had prompted General Douglas MacArthur to drop leaflets over North Korean territory warning that soldiers would be held accountable for war crimes. But later it was all but forgotten.

''When I finally found the area of the execution site, I said, `Someday, I will find the survivors - someday.' It was an act of faith,'' recalled Kangas, 42.

Official records of the massacre were incomplete. Ryan, for one, was declared dead at the hill, and those accounts were never corrected when the 18-year-old recruit recovered. A government documents building in St. Louis burned down in the 1960s, taking records of that day with it. The survivors never knew how to correct the record or even that they could. Once Kangas found the men he launched a campaign to get them recognized for POW benefits and medals.

But first, he had to find them. Nearly a decade after Kangas began his search, another war history enthusiast read an interview with him in a New Jersey newspaper and linked him up with Ryan and the two other remaining survivors, re-uniting the men for the first time.

''They told me Fred was dead. They told me I was the sole survivor,'' said former private first class Roy Manring, 67, a retired maintenance worker from New Albany, Ind.

Manring was shot 13 times and spent 18 months in hospitals in Korea, Japan, and the United States. ''I tried to forget about it. ... I didn't want to talk to anyone about it except my wife. My kids knew I was an ex-POW, but they didn't know what I had been through.''

The time for forgetting ended when Manring met up again with Ryan and former private James M. Rudd of Salyerville, Ky. First they were awarded the POW medal and other honors. This year, they were invited and sponsored by South Korean veterans and US soldiers at Camp Carroll to come back to identify the massacre site for a memorial. Rudd was too ill to make the journey. Ryan, who fears flying, had vowed never to board a plane again after leaving Korea - except if it was to come back.

Ryan and Manring spent the day trudging around the forgotten hillside, now covered with vineyards and partly dug up for a tunnel under construction. After hours in the sun comparing the much-changed terrain to their memories of mortar emplacements and lookout points, Manring froze, fell to his knees on a rock and said he knew this was it.

''I was laying right here after they shot me,'' he said with a shudder. His grandfather appeared to him and ''put his arm on my shoulder and said, `They're coming back, get out of here.''' When Manring struggled up, he was shot five more times by an approaching American unit that couldn't identify his ragged uniform. The victims had been 15 minutes shy of being saved.

The massacre was the culmination of three days of captivity for 67 Americans, Manring and Ryan say, during which the North Koreans tied them together and moved them constantly. The first night, 10 of the POWs were taken away with shovels - presumably to dig their own graves - and never returned. A few escaped overnight, but the second day, when one soldier slipped on the hillside and briefly separated from the others, the angry captors decapitated him with a trench-digging tool.

After taking some minutes by himself in the gulley, Manring whispered, ''I talked to the boys. I hope I'm at peace now. I begged their forgiveness. I have dreams about them all the time. I feel guilty that I survived.''

Ryan, trying to locate the spot where he was shot, recalled being shielded by the body of a 6-foot-3, 280-pound fellow soldier.

''As soon as the North Koreans turned around, I shook the guy on top of me, but he didn't respond. Then I got up and lifted my friend Hernandez. He told me to get down, they were coming back. I didn't talk to him 30 seconds before he died in my arms, and I started crying,'' he said.

Ryan said he stayed alive by thinking of his mother, his girlfriend, and the chocolate malts at his favorite soda shop in his hometown of Dayton, Ky.

The emotion of being in the spot where he almost died finally overtook Manring. ''I'm going to tell you something I've hardly told anyone,'' he began softly. ''I shot a little Korean girl. She was maybe 8 or 10 years old.''

Manring recounted that his platoon was approached one day by a group of refugees, but when he took out his binoculars, he saw a girl holding a grenade in her hands, and no pin in it, headed their way. Before she had a chance to throw it, ''I put a bullet in between her eyes,'' he said, sobbing. ''She bothers me to this day.

''I don't know who that little girl was or who put a grenade in her hands, but the communists will do anything. That's why if I had to fight all over again, I'd do it.''

This story ran on page A2 of the Boston Globe on 06/25/99.

© Copyright 1999 Globe Newspaper Company.