History  On Line

On Line

When the armistice negotiations resumed at the new site at Panmunjom in late October 1951, Item 2- the line of demarcation- was still in dispute and the knotty problems arising from Items 3 and 4 but dimly envisioned. In the light of past experience, however, the task of threshing out a truce proposal acceptable to both sides promised to become a long, drawn-out affair.

There was little doubt that the punishment dealt out as the Eighth Army "elbowed forward" into the enemy positions had sorely depleted the offensive capabilities of the Communists and had influenced them to return to the conference table. But whether they had come back to conclude an agreement or simply to continue the discussions remained to be seen.

Under the circumstances there were two courses of action open to the U.N. Command: (1) it could have the Eighth Army sustain the pressure built up by the summer campaigns upon the enemy until a satisfactory settlement was reached; or (2) it could accept the Communist reappearance at the negotiations as a sign that the enemy was now willing to end the fighting. If the latter proved correct and a line of demarcation was to be established along the general trace of the battle front, then further sustained fighting and heavy casualties would be wasteful and unnecessary. On the other hand, if the Communists intended to use the negotiations to win a breathing period while they replenished their battered forces and strengthened their defenses, the first course offered certain longterm advantages. It might be far less costly to keep up the limited offensive punch already developed and maintain the initiative until an agreement was signed rather than to permit the enemy to regain his balance and settle down to a long war of attrition.

A Choice Is Made

On 27 October, just three days after the truce talks reopened, General Van Fleet set up a plan for an advance into the Iron Triangle on the west and beyond Kumsong on the east. Using the U.S. I and IX Corps, he intended to take over the high ground north of the Ch'orwon-Kumhwa Railroad and establish a firm screen along a new defensive line called DULUTH, south of P'yonggang and north of Kumsong. After the IX Corps attained the dominating terrain around Kumsong, it would push on to the northeast along the road to Tongch'on. In the meantime, the ROK I Corps would move forward along the east coastal road to Tongch'on and link up with the IX Corps just south of the town.1

The operation toward Tongch'on, called SUNDIAL, eliminated the amphibious operation which the earlier WRANGLER plan had envisaged for the east coast, but the objectives were the same- to cut off the North Korean forces caught between the double envelopment and to set up a new defensive line. As things turned out, SUNDIAL was shortlived, for on 31 October Van Fleet was instructed to postpone his attack toward Line DULUTH until he received further orders from Ridgway. The debate over the line of demilitarization was the reason for the delay, since the JCS believed that ultimately the U.N. Command might have to modify its stand and withdraw several kilometers to the south. If this proved to be true, there seemed to be little reason to take casualties for territory that would soon have to be evacuated.2

On 5 November Van Fleet again sought permission to move toward DULUTH, but without success. Ridgway waited until 11 November, then canceled the operation. Without the preliminary advance to DULUTH, SUNDIAL was automatically ruled out.3 A new wait-and-see policy at UNC headquarters was inaugurated with the elimination of the DULUTH-SUNDIAL Offensives.

As the line of demarcation assumed increasing importance to the battlefield, planning at the UNC and Eighth Army headquarters operated on a contingent basis. If the negotiations broke down or became hopelessly ruined, then an offensive might be launched. Plans for an advance to the Wonsan-Pyongyang line and even as far as the Yalu were brought up to date, but Ridgway thought that under present circumstances neither of these offensives would be worth the casualties they would cost.4

The lack of enthusiasm for ambitious offensive operations while the line of demarcation was being arranged was clearly reflected in Ridgway's 12 November directive to Van Fleet to assume the "active defense." Along the general trace of present positions, the order ran, Van Fleet would seize terrain most suitable for defense. He would, however, limit his offensive action to the taking of outpost positions not requiring the commitment of more than one division. At the same time, the Eighth Army commander would be prepared to exploit favorable opportunities to inflict heavy casualties upon the enemy.5

On the following day the JCS sustained the UNC approach. They considered the line of contact existing at that time to be acceptable as the line of demarcation and that contact expected in the next month would not affect its acceptability. "Ground action could still continue even though gains and losses would not be of significance to location line . . . ," the JCS concluded.6 With the JCS and Ridgway in agreement over the unwisdom of other than minimum operations at the front, the fighting settled down to small-scale actions and patrolling.

Evidently the JCS and Ridgway both believed that the Communists were ready to come to terms or perhaps the wish was father to the thought. At any rate Ridgway informed Chief of Staff Collins that he believed the Communists had been badly hurt by the UNC offensives and wanted the earliest possible suspension of hostilities. He pointed to a speech by Andrei Vishinsky, Russian Foreign Minister, before the U.N. General Assembly on 8 November, in which he proposed a cessation of the Korean fighting within ten days and also to the report of the UNC delegates at Panmunjom that the enemy seemed to want an immediate de facto cease-fire as indication of the Communist desire for a speedy end to the Korean War.7 Army intelligence authorities in Washington were cautiously inclined to agree.8

In the light of this general feeling of optimism in Tokyo and Washington, it was not surprising that Eighth Army should absorb some of the complacency. As soon as the line of demarcation was agreed upon on 27 November, Van Fleet told his corps commander that they would make sure that every UNC soldier was aware that hostilities would continue until an armistice was signed. He then went on to instruct them that:

Eighth Army should clearly demonstrate a willingness to reach an agreement while preparing for offensive action if negotiations are unduly prolonged to this end. A willingness to reach an agreement will be demonstrated by: Reducing operations to the minimum essential to maintain present positions regardless of the agreed-upon military demarcation line. Counterattacks to regain key terrain lost to enemy assault will be the only offensive action taken unless otherwise directed by this headquarters. Every effort will be made to prevent unnecessary casualties.9

The Van Fleet order in effect hinged Eighth Army operations upon the enemy's actions and granted what amounted to a cease-fire if the enemy so desired. As the order filtered down to the small unit level, few commanders were willing to risk the lives of their troops unless it became a case of necessity. But when the war correspondents in Korea found out about Van Fleet's instructions, they broke the story, charging that the order had "brought Korean ground fighting to a complete, if temporary, halt."10

Since this charge was essentially true, it caused embarrassment in Washington and in the UNC headquarters. The Associated Press implied that the halt had come on orders possibly from the White House itself and a strong statement was issued by the President on 29 November to counteract the impression. On the other side of the world, Ridgway was quick to explain that Eighth Army had assumed "a function entirely outside its field of responsibility" and that efforts were being made to correct any false impressions that might have been drawn from the Eighth Army order." Artillery fire began to sound again from the UNC lines and Ridgway reported on the 29th that 68 patrols had been sent out and 14 separate attacks repulsed ranging from two squads to a regiment in size.12 The unfavorable publicity from the news stories put an end to the virtual cease-fire and insured that at least lip service would be paid to the oft-repeated avowal that hostilities would continue until an armistice was signed.

But a choice had been made, for as soon as the Washington leaders and the U.N. Command had agreed to the line of demarcation and the thirty-day deadline that went with it, they had also tacitly recognized that further large-scale offensive operations would not be mounted unless the Communists broke off or mired down the negotiations. As long as the enemy continued to discuss the matters under debate, there was little danger that the U.N. Command would again resort to strong ground pressure on the battlefield. In the air and from the sea no such limitations applied. Here the mastery of the UNC still prevailed and casualties could be kept low. But the war for real estate that might eventually be forfeited under an armistice offered little inducement. The winter that lay ahead promised to be filled with frustration for the ground soldier unless agreement at Panmunjom followed swiftly upon the heels of the drawing of the line of demarcation.

The War of Position

Memories of the first winter in Korea and its hardships were still fresh in the minds of the UNC troops. The swiftness of the advance into North Korea and the equally rapid withdrawal that followed in late 1950 had dislocated the supply and distribution lines of the U.N. Command and resulted in shortages of heavy winter clothing and equipment among some units at the front. By the fall of 1951, with the war entering a static phase, the situation was well in hand. Distribution was a comparatively simple matter and experience had led to the modification and improvement of many items of clothing and equipment.

The advent of the cold weather seemed to favor the UNC forces slightly. For the most part, the U.N. Command held the south slopes of the hills and mountains which were frequently free of snow and warmed by the sun. The enemy had to look into the sun and into the deep shadows cast by its rays. In the rear areas, the UNC accommodations were much more comfortable than those of the Communists.

Offsetting those advantages, however, was the enemy ability to overcome the rigors imposed by weather and terrain. The Communist soldiers, many of whom were already acclimated to the weather of North Korea and North China, had borne the harsh winter of 1950-51 with less physical distress than the U.N. Command. Under trying conditions, they had managed to live off the land and to fight vigorously on rations that would barely have provided subsistence for the majority of the U.S. troops.13

And although the UNC forces were adequately supplied with clothing and cold-weather equipment, these were only as good as the men who used them. To remain outdoors in the often arctic cold of the Korean mountains for any length of time required a high degree of coldweather discipline. What good did it do to provide the soldiers with insulated boots if they did not keep spare, dry socks on hand and did not change socks often? Among many of the UNC troops, a winter environment team sent out from Washington reported, there was a fear of frostbite and a lack of knowledge of how to prevent it. This resulted in a high cold-injury incidence and reduced the time that could be devoted to patrol and ambush to an almost ineffective level. Even the bunkers and frontline shelters reflected a lack of ingenuity, the team went on, and were devoid of the simplest principles of winterization.14

As the ground became frozen, new problems arose for the infantryman. Ordinary entrenching tools were adequate for digging as long as the ground was not frozen more than three inches, but tended to break under sterner tests. Picks and shovels were better suited to the task, but were too ponderous to be carried by the troops. One infantry unit met the situation by issuing a 2-pound block of TNT to each soldier for use in breaking through the frozen top layer.15

The distaste of the UNC troops for winter fighting was but an added factor in the course of the ground war. Paramount, of course, was the disinclination on both sides to disturb the status quo radically during the negotiations. But when the cold weather was combined with the halfhearted ground maneuvers, a note of restraint reminiscent of the summer lull of July pervaded the battlefield. The policy of "live and let live" was immediately reflected in the lower casualty reports.

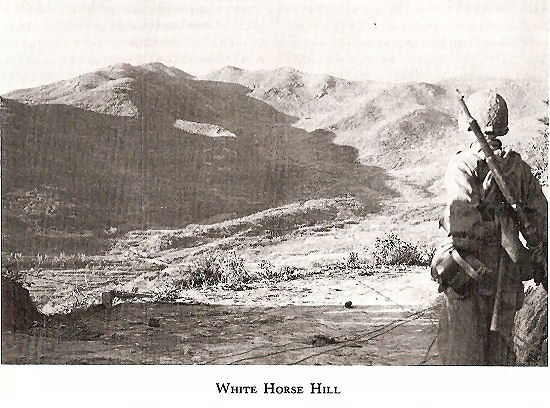

Before the agreement on the line of demarcation on 27 November, the desire for better positions did produce a number of minor engagements along the front. Basically it was a battle for hills and the pattern became all too familiar. The experience of the ROK 9th Division in November was repeated across the trace of battle. Fighting for Hill 395 (White Horse Hill) northwest of Ch'orwon in the U.S. I Corps sector, the ROK 9th first lost the hill on 5 November, then retook it the following day; lost it again on 16 November and recaptured it once more on the 17th.16 Counterattack! Take the hill! Hold the hill! -these were the key commands that dominated the winter war.

During the daylight hours the Eighth Army sent out its patrols and small-scale raids which the enemy sought to intercept. Enemy action, on the other hand, took place chiefly at night, under cover of darkness and unhindered by air surveillance. The Communists confined themselves primarily to patrols and limited probes of the UNC defensive positions.17

The principal clash during November took place in the IX Corps sector east of Kumsong. On 17-18 November the ROK 6th Division, supported by two tank companies of the U.S. 24th Infantry Division and the attached ROK 21st Regimental Combat Team, moved out on a 7-mile front toward a new defense line. Despite strong resistance from elements of the Chinese 68th Army, the ROK division advanced up to two miles. Reaching the new line on the 18th, they dug in against Chinese counterattacks and succeeded in beating them off.18

As the discussions on the line of demarcation came to an end in late November, a change in Chinese tactics was completed. As mentioned earlier, the Chinese had begun to shift from their customary tactics based upon fluid warfare during the early autumn.19 The static conditions of December allowed them to finish their switch to fixed, positional warfare. Adopting a defenseindepth pattern, both Chinese and North Koreans proceeded to fortify their lines. Digging in on hills, they set up gun replacements and personnel shelters interconnected by communication and supply trenches. Everything at hand -logs, rocks, and sand-was used to provide overhead cover and to protect their troops against anything but a direct hit. On the reverse slopes their trenches followed the contours and were 5 to 6 feet deep. Small oneman shelters were dug into the rear wall every 15 to 20 feet. Through the crown of the hill, the Communists fashioned other trenches leading to machine gun and rifle positions along the front and to kitchen and ammunition supply points at the rear. In some cases, they tunneled through the hills and hollowed out huge underground bunkers. Using high terrain features effectively, they laid out fire patterns and often employed personnel shelters as alternate firing positions.

The enemy firing positions were practically artillery proof and certainly mortar proof.20

The U.N. Command had made little attempt to disturb the enemy's efforts to strengthen his defenses. Not that the thirty-day limit on the line of demarcation dictated a suspension of hostilities, but rather a self-imposed restriction on large-scale operations in December precluded any moves of great tactical significance. The Eighth Army "reduced its offensive operations during the month as a demonstration of good faith." In turn the Communists launched mostly company and platoon-sized attacks on the UNC outposts. Only rarely was a battalion-sized assault mounted.21

Lest the Eighth Army lose its edge completely, Van Fleet instructed his corps commanders "to keep the Army sharp through smell of gunpowder and the enemy" by intensifying their programs to capture prisoners of war through ambush. If it appeared that the peace talks would fail, new plans would be prepared around 20 December for a series of limited objective attacks in January designed to strengthen defensive positions.22 With the Communists improving their positions daily, further "elbowing forward" might prove more costly than it had been during the August-October period. As for the capture of prisoners of war via the ambush method for intelligence purposes, the total log for December was a paltry 247, only a quarter of what it had been the previous month.23

As the thirty-day limit expired on 27 December, Ridgway asked Van Fleet for a report on his plans to return to the offensive. The Eighth Army commander's reply showed clearly the change in the tactical situation. He contemplated no offensive action in the near future. In the eyes of his commanders, minor attacks to strengthen the present UNC positions would be costly and without value. The UNC defensive line was strong and could be held against the enemy. Obviously, the Communists were now well entrenched and immune to normal artillery preparation. Only by bold assault could the enemy be dislodged and this could not be done at a low cost. The benefits to be won, Van Fleet concluded, would not justify the casualties certain to be incurred.24 More ambitious plans for an advance to the Pyongyang-Wonsan line met with a similar response. The Joint Strategic Plans and Operations Group found that while such an operation was feasible and could be logistically mounted, it would probably mean that close to 200,000 UNC casualties would be registered. General Weyland, FEAF commander, was not in favor of extending the UNC lines so close to the Communist air bases in Manchuria and suggested a more modest advance as an alternative. And the Navy pointed out that naval vessels and amphibious forces might suffer considerably if the enemy mounted major air attacks from bases in North Korea.25 Under the existing conditions, there seemed to be little possibility of more than academic consideration of largescale offensive ventures at the end of 1951. The losses would be too heavy and the reaction of the USSR uncertain. As long as the desire to settle the war through negotiation remained predominant, it was doubtful that other than minor ground activity would be allowed.

The calm on the battlefield, however, did permit more attention to be paid to one troublesome problem that bothered the U.N. Command almost from the beginning of the Korean War. Behind the lines in South Korea there were over 8,000 guerrillas and bandits, 5,400 of whom were reported armed. Concentrated mainly in the mountains of the rugged Chiri-san area of southwestern Korea, they were a constant thorn in the side of the ROK Government. Although they were chiefly of nuisance value, there was always the chance that in the event of a major offensive, they could pose a real and dangerous threat to supply and communication lines and to rear areas.26

During November there was an upsurge in raiding operations as the guerrillas launched well-coordinated attacks upon rail lines and installations. Fortunately, the raids were lacking in sufficient strength to follow through and inflict serious damage, but Van Fleet decided that the time had come to eliminate this irritation. In mid-November he ordered the ROK Army to set up a task force composed of the ROK Capital and ROK 8th Divisions, both minus their artillery units. Van Fleet wanted the group organized and ready to stamp out guerrilla activity by the first of December. Since the Chiri-san held the core of guerrilla resistance, Van Fleet directed that the first phase of the task force operations cover this mountainous stretch some twenty miles northwest of Chinju.27

On 1 December the ROK Government took the first step by declaring martial law in southwestern Korea. This restricted the movement of civilians, established a curfew, and severed telephone connections between villages. On the following day Task Force Paik, named after the commander, Lt. Gen. Paik Sun Yup, initiated its antiguerrilla campaign, sardonically called RAT KILLER. Moving in from a 163-mile perimeter, Task Force Paik closed on the Chiri-san. The ROK 8th Division pushed southward toward the crest of the mountains and the Capital Division edged northward to meet it. Blocking forces, composed of National Police, youth regiments, and security forces located in the area, were stationed at strategic positions to cut off escape routes. As the net was drawn tighter, groups of from ten to five hundred guerrillas were flushed, but only light opposition developed. After twelve days, Task Force Paik ended the first phase on 14 December with a total of 1,612 reported killed and 1,842 prisoners.28

The hunt shifted north to Cholla Pukto Province for Phase II with the mountains around Chonju the chief objectives. From 19 December to 4 January the ROK 8th and Capital Divisions ranged the hills and sought to trap the guerrillas and bandits hiding in the rough terrain. By the end of December it was estimated that over 4,000 men had been killed and another 4,000 had been captured.29

When Phase III opened on 6 January, the task force returned to the Chiri-san to catch the guerrillas who had filtered back into the area after Phase I. On 19 January, the Capital Division carried out the most significant action of the campaign. While the ROK 26th Regiment took up blocking positions north of the mountains, the ROK 1st and Cavalry Regiments attacked from the south, in two consecutive rings. Although one small group broke through the inner ring, it was caught by the outer circle of troops. What was believed to be the core of the resistance forces in South Korea perished or was taken prisoner during this drive. When Phase III ended at the close of January, over 19,000 guerrillas and bandits had been killed or captured in the RATKILLER operation.30 The last phase became a mopping-up effort against light and scattered resistance. The ROK 8th Division returned to the front in early February, while the Capital Division's mobile units sought to catch up with the remnants of the guerrillas. RATKILLER officially terminated on 15 March, when the local authorities took over the task.31 |

|

While Task Force Paik carried out its campaign in South Korea, action at the front was limited to the patrol clashes and small forays that characterized the defensive, positional war. Chinese forces attacked ROK 1st Division positions on the western front near Punji-ri and managed to drive the ROK forces off in early January. Later in the month, raids by elements of the U.S. 45th Infantry Division south of Mabang-ni drew strong enemy reactions.32 But there was no major change in the line of contact.

Although there was little activity on the battlefield, several interesting experiments were conducted during the winter months. Van Fleet was rather disappointed in the lack of improvement of his artillery units. He wrote Ridgway in December that until early October "there was not a single instance in which a 155-mm. self-propelled gun had been used for close direct fire destruction of enemy bunkers, although this had been developed and extensively used by U.S. forces in World War II against the Siegfried Line."33

Thus, in January, the U.S. I Corps artillery mounted project HIGHBOY. Heavy artillery and armored vehicles were placed on the tops of hills where they could pour direct fire into the enemy positions and bunkers that could not be damaged by normal artillery and mortar fire. Van Fleet noted some progress in the system of reducing enemy fortifications located on steep mountain slopes, but the basic problem remained unsolved.34

The second experiment was more intriguing, though perhaps even less rewarding. Designed to confuse the Communists and lead them into miscues, Operation CLAM-UP imposed silence along the front lines from 10-15 February. No patrols were sent out; no artillery was fired; and no air support permitted within 20,000 yards of the front. Theoretically this change of tactics was supposed to arouse the curiosity of the enemy and make him think that the UNC troops had pulled back from their positions. Then when the enemy sent out his patrols to investigate, the U.N. Command would net a big bag of prisoners by ambushing them. In practice, the enemy was not fooled and used the period of respite to strengthen his defensive positions. When the Eighth Army resumed fullscale patrolling at the end of the period, only a few prisoners were taken.35 The stratagem was not repeated.

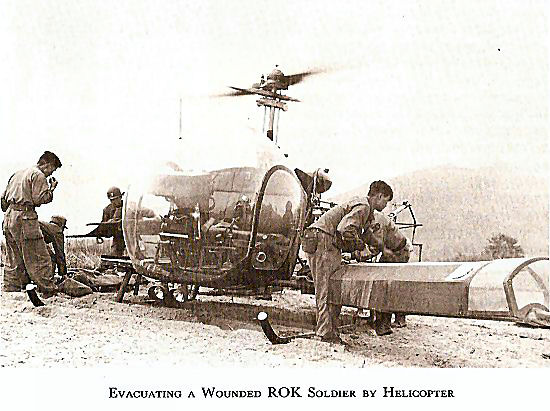

In a third field, the results were much more promising. The rough terrain in Korea had proved to be well suited for the use of helicopters. The light and easily maneuverable aircraft could land in small clearings and evacuate the wounded or bring in needed supplies to isolated units. In Korea the Eighth Army soon discovered another use for them. On 11 November, Marine Helicopter Transport Squadron 161 lifted 950 troops to the front and brought back an equal number and the following month it effected the relief of a second battalion.36

The performance of the Marine helicopters convinced General Ridgway that the multipurpose craft were vital necessities in Korea. He recommended that four Army helicopter battalions be made available to the Far East Command to supplement the Marine squadron. In order to insure a steady flow of replacement craft, he suggested that procurement be started on a scale that would permit manufacturers to expand production immediately.37

In December, Marine and Air Force helicopters recorded another first. During the summer of 1951, the hospital ship USS Consolation had been fitted with a helicopter landing platform. Anchored at a small port on the east coast of Korea just above the 38th Parallel, the Consolation received 245 patients flown in from front-line battle aid stations during the holiday season and early January. These were emergency cases in which speedy attention often meant the difference between life and death or the loss or saving of a limb. In as little as five minutes the egg-beaters could make the trip from aid station to ship and in forty-five seconds they could unload the wounded and clear the deck. Even in choppy seas, when small boats could not be used, the helicopters carried out their mission. The success of the operation was hailed by the captain of the Consolation as "one of the greatest advances made in years for handling of battle casualties."38 |

|

Yet despite the improved facilities for rushing the wounded to the hospitals, there were many who fell who were beyond medical help. The task of patrolling and probing was both monotonous and deadly- monotonous in its dull routine and deadly in the slow but steady toll of casualties that it claimed. No matter how cautious the commanders might be in risking lives unnecessarily, enemy artillery and mortar fire often found their target and enemy ambushes and probes caused the list of dead and wounded to mount. It was a frustrating period of the war- deadlock at the truce negotiations at Panmunjom and stalemate at the front. In many ways the Korean ground war in 1952 seemed to be an anomaly- a throwback to the Western Front of World War I rather than a successor to World War II. The static quality of the battlefield, the defense in depth with its barbed wire and intricate series of trenches, the accent on artillery and mortar fire and the everlasting patrols and raids- all harked back to the 1914-18 period. There were many points of difference, of course, for the airplane had become far more important in the intervening years and gas warfare had been shelved. Better sanitation facilities and the discovery of DDT made life more livable in Korea than it had been in France. But there was no denying the similarities and for troops and officers trained in the war of movement, in fluid tactics, the return to another era necessitated a period of adjustment and many of the lessons of World War I had to be relearned.

Under most circumstances the dragging out of the negotiations and the inaction at the front might have led to a deterioration in morale, but in March the Army G-3, General Jenkins, confirmed Van Fleet's avowal that Eighth Army morale was high. On a trip along the battle trace he found both commanders and troops were confident of their ability to resist anything the enemy could throw at them.39 Van Fleet attributed the healthy mental state of his troops to the liberal rotation policy that had been adopted early in 1951.40

To qualify for rotation during the winter of 1951-52 a soldier had to have nine months of service in the combat zone in Korea or a total of thirty-six points. Each month at the front was worth four points and service elsewhere in Korea was valued at two points a month. From the summer of 1951 on, increasing numbers of personnel became eligible for relief. During the fall and winter of 1951-52 between fifteen and twenty thousand men were rotated each month and this was an important factor in sustaining troop morale. On the other hand, rotation lowered troop efficiency considerably, since it became difficult to maintain training standards and to fash-

187ion battle-hardened teams as long as the units remained in a state of constant flux. The replacements had to undergo a period of indoctrination and of testing before they became battle-wise and by that time another new group of replacements would be on hand to be absorbed. Fortunately, the combat requirements at the time made few demands for veteran troops and the rotation system worked fairly well.

The inactivity at the front did not mean that there was a lack of planning. On the contrary, during the winter and early spring, Van Fleet's staff forwarded plans to Ridgway setting forth a variety of limited operations that might be carried out. The first arrived early in February and was called BIG STICK. It proposed to destroy the Communist supply complex based on Sibyon-ni and to advance the Eighth Army left flank to the Yesong River. In the process Kaesong would be captured and four Chinese armies dispersed at an expected cost of over 11,000 UNC casualties. BIG STICK could be mounted with present capabilities about 15 April and would use an amphibious feint on the east coast by the 1st Marine Division to bolster its chances of success.41

On Washington's birthday, Van Fleet followed up with a second offering. This was a more limited operation called HOME COMING and contemplated using only ROK troops. The objectives of HOME COMING were similar to BIG STICK in that the Yesong River would again be the target, but the attack toward Sibyon-ni and the amphibious feint would be omitted. Kaesong would be regained and Van Fleet considered that the recovery of the old capital of Korea would be an excellent tonic for his ROK forces. If BIG STICK were ruled out, Van Fleet wanted to try HOME COMING about 1 April.42

Since the negotiations at Panmunjom were making some progress by the end of February, Ridgway did not favor any operation that would lead to a rise in casualties. "Pending further orders," he informed Van Fleet in early March, "offensive action will be limited to such reconnaissance and counter-offensive measures as necessary to provide for the security of your forces."43

The lack of enthusiasm for his offensive plans at Ridgway's headquarters did not prevent Van Fleet from trying again on 1 April. Still anxious to use his ROK divisions in a series of limited objective attacks, he set up CHOPSTICK 6 and CHOPSTICK 16. The first envisaged the envelopment of the high ground south of P'yonggang by a reinforced ROK division, and the second laid out a two-division attack to drive the enemy from the area east and south of the Nam River in eastern Korea. In both plans, the ROK forces would be strongly supported by air and artillery and could take advantage of their cross-country mobility and gain valuable training. Ridgway, however, did not like the terrain on the defensive line set up for CHOPSTICK 6, and he turned it down. He approved the concept of CHOPSTICK 16 on 16 April and left its execution to the discretion of Van Fleet with the proviso that no U.S. troops would be used and that he would be notified before the operation was carried out. But, as had happened so often in the past, Van Fleet decided to suspend CHOPSTICK 16 indefinitely on 29 April- the day after the package proposal was presented at Panmunjom.44 Once again the negotiations made their influence felt upon the battlefield.

Night Patrol

The UNC decision to forego limited objective attacks in the spring of 1952 meant that the Eighth Army would continue to make contact with the enemy through patrols and raids unless the Communists changed their tactics. From an intelligence point of view patrols and raids often proved to be quite futile; few prisoners were taken and frequently no enemy contact was effected. Yet the planning and carrying out of these activities kept the front-line troops alert and gave them valuable experience and training under combat conditions.

In April 1952 each Eighth Army regiment at the front usually sent out at least one patrol and set up several ambushes for the enemy every night. The assignment to carry out the daily patrol was rotated among the battalions and companies of the regiment, customarily by a prepared roster indicating the responsibility for patrols some two to three weeks in advance. Thus in late March, Company K, 15th Infantry, 3d Infantry Division, learned that it had drawn the assignment for 16 April.

The 15th Infantry, commanded by Col. William T. Moore, occupied a sector southwest of Ch'orwon and west of Yonch'on. Company K, under 1st Lt. Sylvanus Smith, was responsible for a piece of the front about eight miles west of Yonch'on, just to the west of the big double horseshoe bend of the Imjin River.45 In this area the terrain was made up of small hills flanked by flat valleys covered with rice paddies.

Since the patrol mission was to bring back prisoners, the choice of objectives was extremely limited. The Chinese maintained only three positions within patrolling distance of Company K and the routes to these objectives were well known to both sides. As it turned out, the 3d Battalion commander, Lt. Col. Gene R. Welch, selected a position manned by what appeared to be a Chinese reinforced rifle platoon, located about 1,500 meters north of the main line of resistance. On a boot-shaped hill, called Italy, some 150 meters high, the enemy outpost kept watch over the activities of the 3d Division units to the south. Five hundred meters to the east of Italy across a broad rice valley with a meandering stream lay Greece, a manyridged hill that resembled the Greek peninsula in its outline.

Lieutenant Smith drew up the patrol plan and had it approved at battalion and regimental level. It visualized two rifle platoons reinforced by a machine gun section from Company M moving out in three groups during the evening toward Italy. The security group, composed of the machine gun section and a rifle squad, would take its position on Hill 128 overlooking the valley between Italy and Greece. One rifle platoon, serving as the base of fire group, would move forward to Italy and halt 350 meters from the Chinese outpost. Once the base of fire group got into position, the assault platoon would pass through and attack the outpost from the southwest. Each group would have a telephone (EE-8) and a radio (SCR-300) to maintain contact with the others and with battalion in case it became necessary to request aid or the laying down of preplanned artillery fire along the patrol route. The handles were removed from the phones to eliminate the ringing and noise which might betray the patrol's position and the instruments were to be spliced into the assault line running forward from the main line of resistance. Flare signals were arranged but not used during the patrol. To provide preparation fire, two batteries of 155-mm. guns and one battery of 105-mm. howitzers would fire for five minutes after the base of fire group got into position on Italy. Two 105-mm. howitzers would continue to fire until the assault group was ready to attack the objective.

Since the patrol was to be conducted at night, the riflemen selected to go on the mission were given intensive training in night fire techniques. Using battery-operated lights to simulate enemy fire, the riflemen were taught to aim low and take advantage of ricochets. Sand-table models of the patrol route and objective were carefully studied and the patrol leaders were flown over the whole area to familiarize themselves with the terrain. Since most of the personnel already had been over the ground on several occasions, the members of the patrol were thoroughly briefed by the evening of 16 April. They were also informed that a regimental patrol would set up an ambush on Greece that night.

The majority of the riflemen carried M1 rifles with about 140 rounds of ammunition and two or three hand grenades apiece. The light machine guns in the base of fire group were provided with 1,000 rounds of ammunition and the crews also carried carbines. Each man wore a protective nylon vest for protection against shell fragments. In the security group heavy machine guns were substituted for light at the last moment, since they were to be used in a fixed support mission and the heavier mount would give more accurate overhead and indirect fire.

A hard rain had turned the ground into a sea of mud on 16 April and the night was dark, chilly, and windy with temperatures in the mid-fifties. At 2110 hours the security group under Lieutenant Smith led the way through the barbed wire and mine fields fronting the company positions. Next came the assault group, led by M/Sgt. George Curry, composed of 26 men of the 2d Platoon and 3 aidmen and 2 communications men from company headquarters. The base of fire group, under 2d Lt. John A. Sherzer, the patrol leader, completed the column as it sloshed through the muck down into the valley below. Sherzer had 26 men from his own 1st Platoon, 1 aidman, and 2 communications men. There were also 12 Korean litter bearers accompanying the assault and base of fire groups in the event of casualties.

Smith's security force had no trouble as they climbed Hill 128 and emplaced their machine guns. But a sudden explosion from the mine field in front of the company positions soon halted the assault group. Sgts. Frederick O. Brown and William Upton went back to investigate and discovered that one of the medics and a Korean litter bearer had started late. Losing their way in the dark, they had wandered into the mine field and tripped a mine. Fortunately the mine had fallen forward into an old foxhole, so that the blast had carried away from the two men, who were unharmed. Brown located the approximate spot where the mine had exploded and notified battalion headquarters to rescue the men.

By the time Brown and Upton joined the waiting patrol, a half hour had been lost. As the assault group resumed its advance and rounded the shoulder of Hill 128, another element of delay entered the picture. From the 1st Battalion sector off to the right, flares went off lighting up the two platoons as they swung to the west up the valley leading to Greece and Italy. Everytime a flare illuminated the sky, the patrol hit the ground and waited until the glare subsided. Pleas back to the battalion to have the flares stopped were unsuccessful.

The snaillike pace of the patrol was further slowed by the practice of halting the groups in place whenever a burnt-out cluster of huts was encountered. Cpl. William Chilquist, in charge of the lead squad, checked the huts thoroughly to be sure that none of the enemy was lurking in the ruins. Between the flares and the three groups of huts along the route that had to be reconnoitered, it was well after 2300 hours by the time the patrol reached the last burnt-out settlement close to the foot of Italy.

Since the assault platoon now had to cross a broad stretch of open ground to get to the selected approach ridge to Italy, the base of fire group set up four light machine guns along the bank of the small stream traversing the valley. With Chilquist's squad leading, Sergeant Curry's force moved in single file across the exposed area along the top of an earthen paddy dike where the footing was less sloppy. At 3-yard intervals, the members of the platoon then began to climb to the first small rise on Italy. As the lead elements reached this spot, a voice, speaking in conventional Chinese, broke the silence. A quick word of command, a few seconds of quiet, and then the chatter of a burp gun shattered the night. From the lower reaches of Greece, machine gun and rifle fire swiftly joined in as the Chinese sprang their ambush. Evidently the enemy had set their trap along the north-south valley between Italy and Greece, expecting the patrol to approach their outpost by this route which had been used many times by Americans in the past. Only the fact that the ridge rather than the valley had been chosen as the access path prevented a greater catastrophe.

The initial enemy burst tore through the assault patrol and hit four men. A rifle bullet pierced the protective vest of Pfc. John L. Masnari, one of the BAR men, and ripped into his chest. Mortally wounded, he told his buddies not to bother about applying first aid, moaned slightly, asked for a priest, and then died a few minutes later. He was the first man to be killed in Korea while wearing body armor. The other three men took wounds in the head, arm, and leg-painful, but not critical injuries.

After the shock of the Chinese onslaught wore off, the assault platoon became angry and opened up with every available weapon on the enemy. Sergeant Curry tried the phone to inform the other groups and battalion of his situation, but the instrument did not work. The radio was of no assistance either, since the aerial had been put out of action by a Chinese slug. For the moment, the assault platoon was completely on its own.

Back at the battalion headquarters, Colonel Welch knew that something had gone wrong, but refused to lay on artillery fire until the patrol's location could be pinpointed; otherwise, he might shell his own men. The base of fire group, in the meantime, took cover when the enemy opened up by jumping into the hip-deep stream, since there were no rocks or fences and only one tree to crouch behind. One of the machine gunners was caught by an enemy burst of fire and took four or five bullets in his leg-the only casualty in Sherzer's platoon.

For ten minutes the two engaged platoons from Company K exchanged brisk fire with the Chinese, then the enemy troops withdrew. Curry's force, with four casualties, no communications, very little ammunition left, and the element of surprise gone, decided to pull back and rejoin Sherzer's group. Since the Korean litter bearers had dropped their loads and headed back toward the UNC lines at the outbreak of the fight, Curry's platoon had to carry its own dead and wounded. Using M1's and field jackets, the men fashioned supplementary makeshift litters and started back down the hill; there was no further enemy fire.

Shortly after midnight, the two platoons combined forces and communications with headquarters were re-established. The flares from the 1st Battalion still were going off, despite the urgent pleas of Sergeant Brown to "get the damned flares out." This meant that the patrol and its wounded had to drop or be dropped quickly each time a flare dissipated the darkness. Not only did this delay the return of the patrol, but the rough handling also made the trip very painful for the wounded. The men of the base of fire platoon, in addition, were wet and chilly from their stay in the stream. Nevertheless, the combined group inched their way back toward Company L's position, where they could get the litters through the barbed wire obstacles with less difficulty. At 0330 hours the weary patrol crept into the 3d Battalion lines and gratefully gulped down the hot coffee and doughnuts that awaited them.

Meanwhile the regimental ambush party set up on Greece had moved forward and covered the area used by the Chinese to ambush Company K's patrol; they found no signs of the enemy. In the morning, however, a battalion raiding group discovered a bloody cap and a number of bloody bandages on Greece, indicating that the 8,000 rounds of ammunition fired by the 3d Division patrol at the enemy had found some targets.46

Since the patrol route had been screened the afternoon before, the Chinese evidently had sent their ambush party into position during the early evening hours. Lieutenant Sherzer recommended that a screening force be sent ahead of the main patrol in the future to guard against further ambushes. The battalion commander decided that in the next patrol action the screening force would cover the patrol route by day and then would remain in position until it was contacted by the night patrol.

Company K's experience was but one of hundreds encountered by the Eighth Army during the winter and spring of 1951-52. Some patrols were more successful and managed to bring back a prisoner. Others exchanged shots with the enemy and inflicted casualties, but made no close contact. Many returned with negative reports, for they had found no one to capture or even to shoot at. Patrol, raid, and ambush by the Eighth Army was matched by similar action by the Communists, for this was the pattern of ground fighting for the period.

Taken as a whole the ground war from November 1951 to April 1952 produced few surprises and little change in the defensive positions held by either side. The Chinese dragon kept to his caves and bunkers and appeared chiefly at night, while the American eagle devoted his activity to the sky and hunted mostly by day. As the pressure on the ground subsided, the emphasis on the war in the air mounted. The Air Force, Marine, and Navy planes and pilots provided the main offensive punch during the long winter.

Interdiction and Harassment

The term "offensive punch" may be a trifle misleading in the case of the air interdiction campaign in Korea, since basically this was a defensive action. It was designed as a preventive measure to keep the Communists from building up sufficient supplies and ammunition to launch a general offensive rather than as preparation or support for a UNC attack. During the summer and early fall of 1951 both Air Force and Navy efforts had begun to concentrate on disrupting the enemy's supply lines with some success.47 It was not surprising, therefore, that when the truce negotiations resumed at Panmunjom in October and ground operations sputtered out, the interdiction or STRANGLE operations received top priority.

By striking at enemy communication lines and supply points, the U.N. Command could take full advantage of its dominance of the air over North Korea and make good use of the mobile firepower represented in its air forces. The destruction of enemy equipment and war materiel would hinder the development of reserve stocks so necessary for a sustained offensive, and the disruption of transportation lines would further snarl the logistics problems facing the Communists. Even on minimum rations, the feeding and supplying of one-half to three-quarters of a million men represented a real challenge to the enemy so long as UNC planes ranged constantly overhead.

Thus, during the November to April period, the Far East Air Forces averaged over 9,000 sorties a month on interdiction and armored reconnaissance missions while close air support sorties varied from 339 to 2,461 a month.48 Although the interdiction campaign was undertaken with the approval of General Van Fleet, the disparity between the two efforts occasioned some comment at the time and in this connection the FEAF commander, General Weyland, later wrote a defense of the distribution that bears repeating: I might suggest that all of us should keep in mind limitations of air forces as well as their capabilities. Continuous close support along a static front requires dispersed and sustained firepower against pinpoint targets. With conventional weapons there is no opportunity to exploit the characteristic mobility and firepower of air forces against worthwhile concentrations. In a static situation close support is an expensive substitute for artillery fire. It pays its greatest dividends when the enemy's sustained capability has been crippled and his logistics cut to a minimum while his forces are immobilized by interdiction and armed reconnaissance. Then decisive efforts can be obtained as the close support effort is massed in coordination with determined ground action.

Thus in the fall of 1951 it would have been sheer folly not to have concentrated the bulk of our effort against interdiction targets in the enemy rear areas. Otherwise the available fire power would have been expended ineffectively against relatively invulnerable targets along the front, while the enemy was left free to build up his resources to launch and sustain a general offensive. Such a general offensive, if it could have been sustained with adequate supplies and ammunition, might well have been decisive. Failure to appreciate these facts caused some adverse comment about the amount of close support given the Army, particularly during late 1951 and early 1952.49

In view of the situation on the ground in this period, there was considerable justice in Weyland's observations. There were no important ground offensives that got beyond the tentative planning or contingent phase and even limited objective attacks found little favor after November 1951. With the enemy well dug in and protected by heavy overhead shelter, only accurate flat trajectory fire or a direct hit by a bomb had any effect upon him. Airplanes could not possibly provide the former and found it extremely difficult to carry out pinpoint bombing of such small and well-camouflaged targets. As long as the war remained static, interdiction seemed to be the most efficient use of the UNC air capability.

The other side of the coin was the effect of the interdiction campaign upon the enemy. As the pace of STRANGLE quickened in November, Air Force and Navy pilots sought to cripple the railroads of North Korea. Fighters and fighterbombers attacked locomotives, railroad cars, and vehicular traffic as well without serious challenge from the Communist air forces. Light bombers (B-26's) covered the main supply routes at night and medium bombers (B-29's) kept the enemy airfields unserviceable in addition to bombing marshaling yards and flying close support missions.50 On 18 November carrier-based aircraft inaugurated a combined program of bridge and rail destruction. Naval reconnaissance jets carrying 1,000-pound bomb loads were sent out regularly for the first time in the war against rail facilities and proved to be excellent at cutting roads. By December it often took the enemy as much as three days to repair the railroad breaks he had previously restored in a single day. Yet, despite this, rail traffic continued to move.51 The Communists succeeded in bringing up and issuing winter clothing to the troops even though it often had to be hand-carried on a piecemeal basis. Interdiction made transportation more difficult, but not impossible.52

One reason for the failure of STRANGLE to live up to the expectations of the optimistic code name was the ingenuity of the enemy in devising countermeasures to negate the interdiction program. At the key railroad junction at Sunch'on, northeast of P'yongyang, pilots reported in early November that the railroad bridge was still out of service since two spans were missing. It was only after a night photo was taken that the U.N. Command discovered that the Communists brought up removable spans each night and had been using the bridge right along.53

Early in January, General Ridgway sent his assessment of the interdiction program to the joint Chiefs of Staff. He was convinced that the air campaign had slowed down the enemy's supply operations, and raised the time required to get supplies to the front. It had also diverted personnel and material from the front to maintain and protect the line of communications. By destroying rail and road transportation and a significant quantity of the goods carried, interdiction had placed increased demands upon the production facilities of Communist China and the USSR. These were all valuable, Ridgway went on, but under static defense conditions the Communists were still able to support their troops adequately, and the UNC air forces within their current resources could not hope to prevent them from continuing to do so. Over a period of time the enemy could manage to stockpile supplies at the front and to build up his forces as well, the UNC commander maintained, and improvement of Communist countermeasures and repair capabilities would weaken the effects of the interdiction program in the future.54 In other words, although the enemy was being hurt and impeded in his build-up, Ridgway believed that unless there was a change in the battle situation in which the Communists were forced to increase their expenditures of supplies and ammunition, eventually they would be in a position to launch and sustain a major offensive.

Contrary to the usual pattern of events, things improved before they got worse. During January, the carriers Essex, Valley Forge and Antietam devoted their attention to track cutting. Each carrier was assigned two or three 12-mile sectors to cut and naval aircraft subjected stretches from 1,500 to 4,000 yards in length to such concentrated bombing that almost total destruction of the roadbed resulted. They then followed up by constant surveillance to prevent quick repair. This shift in tactics evidently caught the enemy by surprise and cuts remained unrepaired for as much as ten days. During the last two weeks in January the rail line from Kowon to Wonsan was kept out of operation.55

To meet the UNC challenge, the enemy shifted his antiaircraft guns to the threatened areas and began to take a heavier toll of the attacking planes. In turn, the naval planes sought to counteract the antiaircraft concentration. A flak suppression strike was mounted with jets hitting the antiaircraft just before the prop-driven planes arrived to bomb the rail lines. This proved effective especially after photoreconnaissance had spotted antiaircraft positions in advance.56

In addition to heavier flak concentrations, the Communists also used their manpower resources to the hilt. The North Korean railroad bureau had three brigades of 7,800 men each that devoted full time to railroad repair. At each major station 50 men were assigned to handle the more skilled tasks and roman teams were spaced every four miles along the tracks. As soon as a rail walker reported a break, these units swung into action. Local labor was rushed to the scene to refill the holes and rebuild roadbeds. At night the experienced crews could move in and restore the ties and rails. The Fifth Air Force estimated that as many as 500,000 soldiers and civilians were engaged at one time or another in counteracting STRANGLE.57

The increasing effectiveness of the Communist crews and labor forces was attested by the naval pilots in February: "The Communists have constantly been able to repair a given stretch of track on a vital rail line in twelve hours or less. On occasion repair crews were found repairing fresh cuts while strikes were still being made."58 Primitive as his tools and methods might be, the enemy managed to restore service quickly and that was all that counted in this battle of machines against men.

The Communists were also making full use of the many tunnels in the mountainous terrain to conceal their trains during the daylight hours. Ammunition and fuel cars were placed in the middle section of the trains, so that UNC attempts to skip bombs into the tunnel mouths resulted merely in temporarily blocking the entrances. With local labor the Communists were able to clear the debris quickly and proceed on their way by nightfall.59

At any rate the returns from STRANGLE became less and less in the face of the Communist countermeasures and the costs mounted. Even the weather seemed designed to help the enemy, for as the ground froze many of the bombs bounced off the hard surface and exploded harmlessly in the air. Some even sent their blast upwards and damaged low-flying UNC planes. Finally, in March, after the spring thaws began, FEAF decided to initiate a new phase, which was called SATURATE, based on the tactics used by the Navy in January. By focusing the destructive power of the air forces upon a specific stretch of roadbed on an around-the-clock basis, FEAF hoped to wreak havoc with rail service. An intense effort on 25-26 March against the line between Chongju and Sinanju proved disappointing. Although 307 fighter-bombers, 161 fighters, and 8 B-26's were used in the strikes, the Communists repaired the breaks in six days and in the meantime, other portions of the rail net were free from interference.60

The greatest weakness in the cycle of rail attack lay in the inability of the UNC to devise effective techniques to continue the bombing at night and during the foul weather. Despite the constant destruction of rail and bridges by day, the enemy was organized to cope with the air assault and repair the damage quickly at night and during poor flying weather. By the end of April the interdiction campaign had reached an impasse. Based upon past experience, it was evident that the air forces available to General Ridgway could not maintain the sustained effort required to keep the railroads inoperable. And obversely, it was also apparent by this time that the large augmentations that would be needed to do the job adequately were out of the question.61

In assessing the value of interdiction, Eighth Army had these thoughtful words to pass on to Ridgway in mid-March:

The success of the interdiction program can best be estimated by assuming its absence. If there had been no Operation STRANGLE the enemy would now have a rail head in the vicinity of SIBYON-NI served by an excellent double track line and in the central sector he would have another important rail head somewhere between PYONGGANG and SEPO-RI. In this event, his expenditure of artillery and mortar ammunition could have been increased many times.

The air interdiction program has not been able to prevent the enemy from accumulating supplies at the front in a static situation. It has, however, been a major factor in preventing the enemy from attaining equality or superiority in artillery and other weapons employed at the front. Thus it has also decreased the offensive and defensive capability of the enemy.62

Although the interdiction operations in the air were more widely publicized, naval surface vessels also contributed to the effort, especially along the eastern coast of North Korea. During poor flying weather the 5-inch guns of the fleet destroyers kept the coastal railroad under fire. The destroyer barrages could not make the initial break in the rails, but they could help keep the line cut by harassing fire.63

Heavy naval ships concentrated on troop targets along the east coast. The battleships New Jersey and Wisconsin, the heavy cruisers Toledo, Los Angeles, Rochester, and St. Paul, and the light cruiser Manchester supported the ROK I Corps during November and December close to the bomb line.64 Farther north British Royal Marine Commando units carried out several raids on Tanch'on and one on Wonsan Harbor during December. In the meantime, the Communists became active on the west coast. Under cover of night they landed raiding parties on offshore islands held by ROK adherents north of the 38th Parallel. The vulnerability of many of these islands lying close to the coast to seizure by determined enemy efforts led Admiral Joy to seek ways and means to strengthen the guerrilla garrisons. By adding ROK Marine units as reinforcements to the guerrillas, Joy hoped to stiffen their defensive capabilities.65 On 6 January the responsibility for island defense north of the 38th Parallel was turned over to the Navy, and Task Force 95 was given the task of providing support for the ROK marines and guerrillas holding the outposts.66

As the island defenses were tightened, the Communists encountered more resistance in their amphibious operations. In February a battalion-sized attack on the island of Yang-do about twenty miles northeast of Songjin on the east coast was repulsed as United States and New Zealand surface vessels helped the ROK marines and guerrillas. Eleven sampans were sunk by naval gunfire and over 75 of the attacking forces were killed.67 After this setback the enemy shifted his attack back to the west coast and in March overwhelmed the Korean Marine garrison on Ho-do which lay about twenty miles southwest of Chinnamp'o. Although the enemy withdrew after three days, Ho-do was not reoccupied since it lay too close to the mainland and was open to follow-up raids.68

While the battle for the islands went on, the JCS considered the possibility of introducing a more dramatic note into the war. In early February they recommended that the Air Force and the Navy conduct a sweep along the China coast to spur the Chinese in the peace negotiations. But the State Department did not want to cause Prime Minister Churchill any further embarrassment. Since British opposition leaders had been accusing Churchilll of approving new courses of action in the Korean War during his January visit to Washington, the State Department felt that a China sweep at this time would tend to confirm these suspicions.69

The commander in chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, Admiral Arthur W. Radford, picked up the idea of a China sweep in March, but General Ridgway, too, had some doubts. He told Radford that while he favored such an operation at an opportune moment, he felt that it would cause adverse political repercussions if it were carried out at that time. Under the circumstances, Ridgway preferred to hold off and wait for further developments at Panmunjom.70

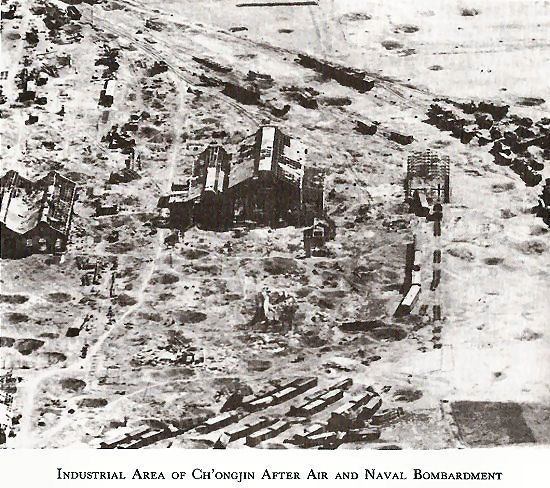

The postponement of the carrier sweep delayed the introduction of a change in pace in naval operations until the following month. In mid-April, however, the carriers Boxer and Philippine Sea sent out four strikes against the important communications center of Ch'ongjin and dropped 200 tons of heavy bombs on the city. From the sea the cruiser St. Paul and three destroyers fired their 8- and 5-inch guns at Ch'ongjin for a whole day. Not only was considerable damage done to installations, but the naval pilots also got welcome relief from the monotonous rail interdiction campaign.71

Naval operations during the November-April period produced little major excitement. The North Korean port of Wonsan received its daily bombardment and mine sweepers ploughed their way with regularity along the coast. Almost every month hits were scored on UNC vessels by the Communist shore batteries, but the damages were usually small and the casualties low. The interdiction campaign occupied the bulk of the carrier planes, but the Marine air squadrons managed to devote most of their attack to close air support missions. Normal blockade and reconnaissance operations continued as in the past, with a close watch on the enemy build-up. Although there was no significant change in the use of the Communist air potential during the period, the danger of sudden and powerful strikes was always a possibility and the UNC naval forces had to remain alert and ready for hostile air action.

The Shifting of the Balance

The paralyzing effect of the truce negotiations upon the battlefield was demonstrated time and time again during the winter and spring of 1951-52. In the shuffle one offensive plan after another was examined and discarded either as being too costly in casualties or too likely to have an adverse influence upon the course of negotiations. Some of the ramifications of the pursuit of the "active defense" have already been considered in connection with the ground, air, and sea campaigns, but there were others that deserve to be examined.

As soon as the war settled down into its static phase, the number of casualties dropped dramatically. Estimates of Communist casualties fell from 80,000 in October 1951 to 50,000 in November, to 20,000 a month in December and January, and then hovered between the 11-13,000 a month mark through April.72 During the same period the UNC battle casualty rate decreased from 20,000 in October to 11,000 in November, to 3,000 a month in December and January and remained under the 2,500a-month mark from February through April.73

The sinking casualty figures could have a number of end results: an expanding replacement pool; a cutback in the number of replacements requisitioned each month to keep the front-line units up to strength; or the initiation of a rotation program to relieve front-line troops. The Communists decided on the first course of action in their desire to improve their position vis-a-vis the U.N. Command. From a low of 377,000 men on 1 November, the Chinese Communists grew to an estimated 570,000 on 1 December and a total of 642,000 by the first of the year.74 The North Koreans evidently were not required to do more than maintain their forces at about 225,000 men during the last months of 1951.75

The UNC, on the other hand, chose the third alternative. During the six months between 1 November and 30 April, U.S. ground force strength, including the marines, dropped from 264,670 to 260,479. Each month between 16,000 and 28,000 replacements were sent out from the United States and men who had served enough time at the front to qualify for rotation were sent home. As has been noted before, the policy helped to sustain morale but it also served to depress the relative strength of the UNC ground forces vis-a-vis the Communists. Despite a small increase in the contributions of the other U.N. countries-from 33,258 to 35,912- and an almost 60,000-man rise in ROK ground force strength- from 281,800 to 341,113- during the same six months' span, enemy superiority in manpower continued to mount.76

Just how much the enemy had improved his military position since the initiation of negotiations in July became apparent in a comparative estimate submitted by the Army G-2, Maj. Gen. Alexander R. Bolling, in late April. In the ten months, enemy strength mounted from 502,000 with 72 divisions to 866,000 with 82 divisions. Artillery supplies quintupled from 8,000 rounds to over 40,000 rounds and artillery units climbed from 4 CCF divisions and some underequipped North Korean units to 8 CCF divisions and 4 well-equipped N.K. brigades. From practically no armor in July, the Communists now had 2 Chinese armored divisions, 1 North Korean armored division, and 1 mechanized division, with an estimated 520 tanks and self-propelled guns. Most of the new material was of Russian design or manufacture. Supply problems had lessened for the Communist forces during the negotiation interval and the combat efficiency of the enemy had shown steady improvement.77 Certainly the Communists had made good use of the respite generated by the truce talks and were in excellent position to continue the stalemate as long as it suited them.

In the air a similar development had taken place. Bolling estimated that the Communists had raised their forces in Manchuria from about 500 planes in July to approximately 1,250 in April, of which about 800 were Russian jets. Seventy-five transports had also been added to the enemy air fleet.78 Actually the Communist air forces had imitated the pattern set forth on the ground. Although their air capability had increased steadily, they had made no serious attempt to challenge the UNC during the winter and early spring. They flew an estimated peak of 4,000 jet sorties in December, but thereafter the total declined to about 2,300 in April. After 1 January they made little attempt to keep their airfields in North Korea serviceable and few enemy fighters strayed south of Sinanju.79 The air potential was there, but like the ground challenge, it seemed to be latent rather than patent during the dormant phase of the war.

Despite the quiescence of the enemy, General Ridgway and his staff were worried about the growth of Communist air power. As he told the JCS in December, he believed that he needed a total of eight F-86 Sabrejet wings to maintain a bare numerical parity with the enemy in fighter-interceptor strength.80 But his message met with little encouragement in Washington. The Joint Strategic Plans Committee pointed out that Ridgway had five squadrons of F-86's or one and two-thirds wings now. To provide him with six and one-third more wings was impossible, since U.S. production amounted to only thirteen planes a month and Canada's production of twenty a month was committed to NATO. The JCS realized that they could not fill Ridgway's request, but they attempted to work out a lesser increase. In early January a carrier was being sent to the Pacific and he could have that if he wanted it; there was also one Marine jet squadron due to arrive in the western Pacific in January that could be assigned to the Far East Command.81

These were frankly stopgap measures, but the Air Force staff examined its resources and quickly came up with several suggestions. Three squadrons of F-94 Starfire all-weather fighters could be spared from the Air Defense Command in the United States although it would mean sending pilots who had already served a tour in Korea back again. The Air Force also wanted to have the State Department negotiate the release of seventy-five F-86's in the U.K. and seventyfive in Canada which could then be shipped to Korea if crews were available. This would cut Canadian air defense to a minimum and delay the build-up of NATO air forces, but under the circumstances, Army planners joined their Air Force counterparts in supporting Ridgway's need for additional air power as being more urgent.82

As it turned out, the upshot of all the efforts to increase Ridgway's fighter force was a fairly modest augmentation, but considering the complicated factors involved it was a good try. One squadron of F-94's was sent to the Far East Command in February and the United States made arrangements with the Canadian Government to purchase sixty F-86's at ten per month. Adding this to the U.S. production available would enable Ridgway to achieve by June two operational full strength F-86 wings that would be backed by a 50-percent reserve.83

The carrier Philippine Sea arrived in the Far East in January to fulfill the JCS promise of another carrier, but Admiral William M. Fechteler, the Chief of Naval Operations, notified the JCS that it could not remain permanently unless the Navy were allowed to retain two carriers due for retirement as a result of the reconversion program then under way. The Air Force opposed the retention since it thought that the Navy could transfer two carriers from the Atlantic-Mediterranean on a temporary basis. In the absence of agreement on this matter among the JCS, Secretary Lovett ruled that the Navy was justified in hanging on to the carriers as long as there was no sign of settlement in the Far East and the possibility of a widening of the war existed. If reduction was made in American naval forces in the European area, unfortunate political repercussions might result. The President agreed and Ridgway was informed that he could keep the additional carrier until either a truce was arranged or his air forces were built up to a point where he could release the carrier.84

Ridgway was less fortunate in his plea to the Chief of Staff for additional antiaircraft battalions. It will be remembered that Collins had granted him an increase of 5 battalions in mid-1951 and 4 of these had arrived in the theater by November. But the growth of enemy air power and the construction of several UNC airfields had created new requirements for antiaircraft defense. Accordingly, in January, the Far East commander asked for 9 more battalions to be sent as soon as possible. In this instance, he encountered a stone wall. There were no AAA battalions that could be spared, Collins told him, in view of the many world-wide U.S. commitments.85

Lack of action on the battlefield dimmed prospects for large augmentations to the UNC but did permit several shifts within the command. Without doubt the most important of these transfers involved the movement of the U.S. 45th and 40th Infantry Divisions from Japan to Korea to take the places of the 1st Cavalry Division and the 24th Infantry Division.

On the surface this appeared to be a routine rotation of divisions, but actually there was considerable background to the exchange. The 40th and 45th were both National Guard divisions that had been sent to Japan in April 1951 to finish their training while furnishing extra security for Japan. In view of the interest of Congress in the commitment of National Guard divisions to combat, the Army sought and received confirmation from Ridgway in July that he did not intend to commit either of the divisions to combat piecemeal.86

In August the JCS informed Ridgway that they wanted the divisions employed in Korea when they completed their training and the U.N. commander agreed. But the development of the summer offensive caused Ridgway to change his mind. He did not want to give up combat-wise divisions for untrained troops as long as there was any danger of an enemy counteroffensive. Besides, he told the JCS, a transfer would disrupt his ability to defend Japan for a period of three months while the transfer was taking place.87

In Washington, the Army G-3, General Jenkins, disagreed. He thought the risk in leaving Japan partially exposed temporarily to be far less than the threat in Korea. Furthermore, he pointed out to Collins, many of the National Guardsmen in the 40th and 45th would come to the end of their term of service in August 1952 and would have to be sent home. He recommended that one National Guard division be shipped to Korea and then, at an opportune moment, one of the combat divisions could be withdrawn and rotated to Japan. This process could be repeated later on with the second division. Both the JCS and the President approved of this procedure in mid-September.88

But Ridgway was not convinced. He held that until at least 15 November the danger of a Soviet move against Japan would still be possible. The Russian reaction to the Japanese peace treaty was as yet unclear and the situation in Germany was also doubtful. He urged postponement of any movement until November when the matter could be reviewed. In the light of Ridgway's reclama, the JCS, with Presidential approval, rescinded their directive to effect the National Guard transfer.89

When early November arrived, Ridgway changed his reasons for objecting to the shift of the two divisions to Korea. Although the Eighth Army had completed the fall offensive by this time, Ridgway did not want to reduce its combat effectiveness in case other operations might be carried out to put pressure upon the enemy in the negotiations. Instead he urged that restrictions against using the National Guard divisions for replacements be lifted.90

General Collins would have no part of this. In his opinion an attempt to break up the divisions would invoke a storm of protests from Congress and imply that the National Guard divisions were not fit for combat duty after a year of training. He informed Ridgway that it appeared mandatory to use the divisions as units as soon as possible before their time expired.91

The Chief of Staff's arguments settled the matter. On 20 November, General Hickey told Van Fleet that the 45th Division would begin its movement in December to replace the 1st Cavalry Division.92

When the actual transfer began, the Far East Command employed a technique that had been developed during World War II in the Pacific. In 1944 the 38th Division had been shipped to Hawaii, disembarked, and had taken over the quarters, equipment, and weapons of the 6th Division. The 6th had been loaded on the ships that had brought the 38th and had then been sent to the Southwest Pacific. By using the same shipping for both relieving and relieved elements and swapping all heavy equipment and supplies, all the men would have to carry would be personal arms and equipment. It was an economical method that obviated on- and off-loading of divisional equipment and speeded up the whole exchange procedure.93

The 45th and 1st Cavalry Divisions began their rotation cycle in early December. As the first echelon- the 180th Infantry Regiment- arrived on 5 December, it was assigned to the U.S. I Corps. Two days later, the 5th Cavalry Regiment sailed for Hokkaido to become part of the U.S. XVI Corps. On 17 December the 179th Regiment reached Inch'on and the following day the 7th Cavalry Regiment left for Japan. The final echelon- the 279th Regiment- came into Korea on 29 December and on the 30th the 8th Cavalry Regiment completed the exchange. By that time the 180th Regiment had taken its place on the line and received its baptism of fire.94

With the experience of this shift under its belt, the Far East Command prepared for the second step. The warning order for the exchange of the 40th Division and the 24th Division was issued in December and in early January the movement commenced. The 24th Division left behind the 5th Infantry Regiment which had been attached to it in Korea, since it was contemplated that the 34th Infantry Regiment which was organic to the 24th Division would rejoin it in Japan. By early February the 40th Division had taken over the responsibility of the 24th in the IX Corps area near Kumsong. The smoothness of the operation was reflected in the story of the gunner in a 24th Division artillery unit who was engaged in carrying out a fire mission. He reportedly passed the lanyard to his 40th Division replacement and set out for the waiting trucks while his guns sent a 40th Division salute to his departure at the enemy.95