History  On Line

On Line

The dramatic development of the prisoner of war issue during the winter months tended to obscure the questions of a more technical nature confronting the two delegations at Panmunjom. Human emotions were involved in the fate of the men confined behind the barbed wire, while the matter of airfield construction and rehabilitation appeared dull and prosaic in comparison. Yet the struggle in the conference tent over Item 3 was every bit as spirited as the dispute over the prisoners; for the delegates of both sides were also military technicians. They understood only too well that the disposition of the prisoners of war was a transient problem which would be shortlived no matter which way it was finally decided. The keeping of the truce, on the other hand, seemed likely to become a long-term affair that might plague the Korean scene for years to come. Under these conditions it seemed essential to assure that adequate safeguards and guarantees were written into the armistice agreement.

Narrowing the Issues

By mid-December the discussion on Item 3 had disclosed the main areas of disagreement. First and foremost among these was the knotty question of airfields which had engendered the bulk of the arguments. And close behind lay the matter of rotation, the composition of the neutral nations observer teams, and the number of ports that were to be permitted to handle rotation and replenishment of men and supplies. These promised to be the most difficult to settle, since the positions taken by the two sides were so far apart.

It was at this juncture that the UNC delegation lost another of its capable spokesmen. General Hodes was given another assignment just a few days after Admiral Burke had been transferred. Able and tough, the two men had worked well together and proved themselves competent to match the best that the enemy had to offer in the negotiations. Instead of Hodes, General Ferenbaugh, who had been serving his apprenticeship for several weeks, joined General Turner on 17 December as a full-fledged delegate.1 It was a difficult task that faced the new Army representative for he not only had to replace General Hodes but also had to contend with the best man on the Communist team- the sometimes profane but always efficient General Hsieh.

In the skirmishes that had taken place so far the U.N. Command had adopted an adamant position against the construction or rehabilitation of airfields and the Communists had refused to listen to any argument imposing restrictions on their freedom to do as they pleased in this matter. Several times during the debates in the latter half of December, Hsieh had intimated that his side would be willing to forget its objections to rotation and replenishment if the U.N. Command would reciprocate on the airfield issue, but his hints fell upon barren ground.2

In an attempt to break the impasse, the negotiators briefly turned the problem over to their staff officers for several days to see if they could narrow the differences in a less formal atmosphere, but this proved to be a futile hope.3 The arrival of the thirty-day limit on the line of demarcation on 27 December was marked by no significant change in the negotiations or on the battlefield. It appeared that the forebodings that the line might become a permanent one until an armistice was signed were well founded.

Toward the end of December the United Nations Command offered a concession. If the Communists would accept the restrictions on airfields, the UNC would forego aerial observation and photoreconnaissance flights. The enemy reaction seemed to sustain the oft-repeated complaints of Ridgway and Joy over the unwisdom of giving the Communists an opportunity to get something for nothing. Hsieh accepted the concession most willingly, but would not budge in his stand on the airfields. Furthermore, he told Turner frankly: "you want to sit on top of other people's heads, and when you come down from that position you say that is a concession on your part."4 The implication that the U.N. Command had simply receded from an unreasonable and untenable position rather than offered something of value was plain. In Admiral Joy's opinion, the weakening of the UNC position merely hardened the enemy's determination to secure further concession on the airfield issue.5

The Communists were well advised on this score, for during the latter part of December, there had been a steady deterioration in the United Nations resolution to insist upon a strict limitation of airfield construction and rehabilitation. This could be traced to the growing reliance on the part of the United States upon a "broader sanction" declaration to be issued as soon as an armistice was signed.6 As the emphasis shifted from dependence upon control of local conditions in Korea to the threat of a larger war if the armistice were violated, the airfield question became less important, especially since it was recognized that it would be difficult if not impossible to prevent the enemy from rehabilitating and building airfields once the armistice went into effect.

To General Ridgway this trend was disturbing. He failed to see how the U.N. Command could pose a deterrent threat to a later outbreak of hostilities if the enemy were permitted to strengthen its air capabilities at will while the UNC air power remained static or decreased. He felt that the Communists sensed the lack of a firm and final UNC position on airfields and that newspaper reports from the United States intimating that the U.N. Command was considering further concessions did not help the situation.7

Ridgway's brief for a hard and fast stand was too late. On 10 January the U.S. military and political leaders informed him that his final position would be the omission of any prohibition on airfield construction or rehabilitation if the issue became the sole obstacle to an armistice. But until the Communists showed that this would be their breaking point, there should be no open concession. As a suggestion they urged that the delegations settle all the other matters outstanding under Items 3, 4, and 5 and defer further discussion of airfields until then. At that time, the U.N. Command could drop the airfields requirements if the Communists would sign the armistice. In this way, they argued, the concession could soon be followed by the U.N. declaration including the "broader sanction" of an expanded war. The issuance of the declaration should counteract the propaganda value that the enemy might attempt to gain from the UNC retreat on airfields.8

With considerable misgivings, Ridgway agreed. He did not have the confidence that his superiors possessed in the possible effectiveness of the U.N. declaration, but he proposed to shunt the airfield question aside if the enemy would consent. Under the present conditions, he was extremely dubious that the Communists would neglect to press their, advantage. Anticipating further concessions, he believed that they would refuse to take up new topics until the matter was settled.9

There were no immediate effects of the Washington instructions in the tent at Panmunjom, for an opportune moment had to be selected for the presentation of the UNC proposal. In the meantime, the arguments between Turner and Ferenbaugh on the one hand and the wily Hsieh on the other continued. The latter stood foursquare behind the slogan "no interference in internal affairs" whenever the UNC delegates brought up airfields. Hsieh's concern over the invasion of North Korea's sovereign rights led Turner to question his sincerity. Since the North Korean air force was depleted, whose sovereign rights was Hsieh interested in- North Korea's or China's, Turner asked. The Chinese general ignored the question.10

On 9 January the Communist delegation introduced a new version of Item 3 that was closer to the objectives that the U.N. Command sought. But as a matter of tactics Turner attacked the weak points and omissions in the enemy's proposal. He could not understand, he told Hsieh, why the Communists were willing to allow the neutral nations observation teams to inspect behind the lines- a clear case of internal interference in his opinion- and yet balked at airfield restrictions. But Hsieh could see no inconsistency in the two matters. The neutral nations were acceptable as a measure to stave off foreign interference, he maintained.

There was no provision for restrictions upon airfields in the Communist version, but it did permit replenishment of military personnel, aircraft, weapons, and ammunition as long as there were no increases. Since this had been the UNC contention from the beginning, Turner quickly took a leaf from Hsieh's book and termed this provision no concession at all, but merely recognition of the justness and reasonableness of the UNC stand. Although Turner turned down the Communist offering because it ignored the airfield issue, the area of dispute was growing smaller.11 The enemy's withdrawal from a firm antireplenishment position served to compensate for the UNC surrender of aerial inspection and photoreconnaissance and indicated that there was still room to bargain on Item 3 as long as the discussion avoided airfields.

In any event there was a gradual shift in the UNC drive to secure modification of the enemy attitude during mid-January. The UNC delegates directed their fire at the Communist motives in insisting upon freedom to rebuild their airfields, but the attempts to pin down General Hsieh were unsuccessful. He insisted that an agreement not to introduce any reinforcing aircraft into Korea covered the UNC objections yet refused to state categorically that the Communists would not increase their military air capability during an armistice. This placed the matter in the realm of good faith and since the U.N. Command was unwilling to lean on so slim a reed, little progress was made.12

Hsieh was not content to remain on the defensive, however, for he vigorously attacked the UNC concept that the balance of military capabilities in Korea should be maintained after the armistice. It was a familiar argument urging that the state of war should be eliminated entirely and all foreign forces withdrawn from Korea; still, on the surface at least, it sounded reasonable. The Chinese general asserted that it would be impossible to retain the status quo during a truce since the U.N. Command was already engaged in increasing its postarmistice strength by expanding the ROK Army.13 Hsieh did not mention that the Communists were engaged in the same task with the North Korean forces, but he had a point.

In late January, the U.N. Command decided that the time was propitious to turn the problem of working out the details on Item 3 over to the staff officers. This would permit further discussion of airfields to be postponed as the Washington leaders had suggested and allow the negotiation of some of the minor differences to be given more attention. Hsieh agreed on 27 January that the subdelegation should recess until the staff officers finished their efforts.14 If the latter could eliminate all issues except the question of airfields, the U.N. Command would then be in a better position to offer a final trade.

Settlement of Item 5

As the staff officers began their meetings, General Ridgway and Admiral Joy determined to suggest simultaneous discussion of Item 5 of the agenda. It will be remembered that this had been simply stated in July as "Recommendations to the governments of the countries concerned on both sides." The was intentionally vague, since the United States had no desire to commit itself in advance on political matters beyond the purview of the military armistice.

In early December General Ridgway and his staff had drawn up an initial position that hewed closely to the July formula. Each side would recommend to the governments concerned a political conference to discuss appropriate matters left unsolved by the armistice agreement. This was a nice indefinite proposal that would bind no one.15

Two weeks later, the President and his advisors decided that mention should be made of the unification of Korea under an independent, democratic government, and they instructed Ridgway to include this in his first approach to the Communists. If the enemy insisted upon a reference to the withdrawal of foreign troops, they authorized the Far East commander to put it in.16 They cautioned him a few days later, however, not to make any commitment on the countries that would participate in the political conference nor on the form or forum of the discussions.17 These details would be left open to settlement on a political level after the armistice was signed.

Ridgway initially did not question these instructions, but by the end of January he had some second thoughts. Suppose the Communists tried to insert the names of the countries that would take part in the political talks, he asked his superiors, should he reject all names or accept only the North Korean and Chinese Communist Governments? And since the enemy probably would press for the inclusion of a ninety-day time limit for calling a conference, the U.N. commander felt that he could make the U.N. proposal more palatable to the Communists by anticipating this move."' The Department of Defense and the Joint Chiefs had no objection to the latter suggestion, but they were still reluctant to have names of countries mentioned in the agreement. If it became necessary, on the other hand, they conceded that the recommendation to take steps at a political level to deal with matters unresolved by the military armistice might be addressed to the specific states concerned. The Soviet Union would be addressed only as a member of the United Nations and not as an individual government.19

Thus, on the eve of the reconvening of the plenary conference in early February, the United States position on Item 5 was extremely cautious. Since the outlook for an early and satisfactory solution of the political situation in Korea did not appear to be encouraging, the American political and military leaders preferred to go very slowly and to operate on an opportunistic basis. Foreseeing a long and involved struggle with the Communists over Korea's future, they favored a flexible approach with few or no advance commitments. Under these conditions, if no final arrangement could be reached, the chances for working out a modus vivendi would be improved.

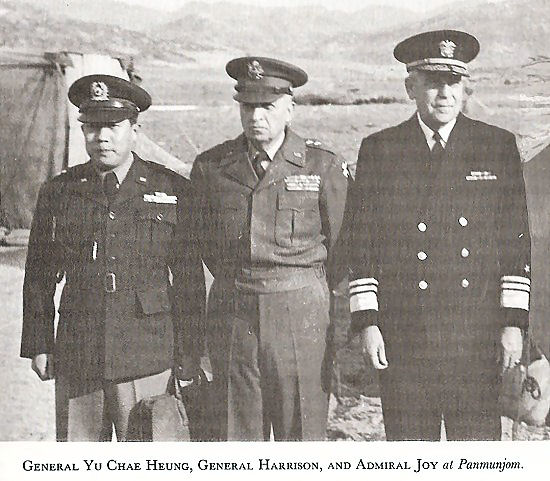

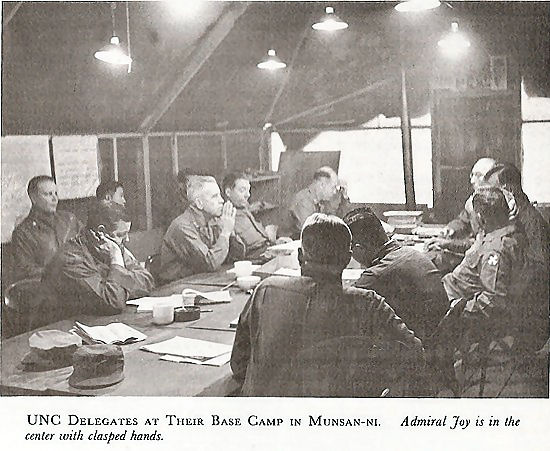

The Communists had insisted that the principles involved in Item 5 be taken up in a plenary session, and on 6 February the full delegation met once again. Joy presented two new members of the UNC group, Lt. Gen. William K. Harrison, Jr., and Maj. Gen. Yu Chae Heung, to General Nam. Harrison replaced General Ferenbaugh and Yu took the place of Gen. Lee Hyung Koon.20

As soon as the amenities were disposed of, Nam introduced the Communist solution to Item 5. He proposed that within three months after the armistice was signed, each side should appoint five representatives to hold a political conference. As for the topics to be discussed, Nam listed three: 1. withdrawal of all foreign forces from Korea; 2. specific recommendations for a peaceful settlement of the Korean question; and 3. other problems related to peace in Korea.21

After a three-day recess the U.N. Command made its counterproposal. Since Ridgway felt that the differences between the two sides were not large, he recommended that the UNC version adopt as much of the Communist wording as possible and the JCS agreed. Nevertheless, reference to five representatives was eliminated and the withdrawal of "foreign troops" became "non-Korean troops." Under the third topic the Communists had listed for discussion, the U.N. Command had changed the wording so that it now read, "Other Korean questions related to peace." The Republic of Korea was named along with the United Nations as an addressee for the recommendation of the military commanders and the portion pertaining to the political conference was made more vague.22

Most of these changes were minor but the Communists preferred their own proposal and a week's debate ensued. The U.N. Command made it clear that it did not intend to recommend that the political authorities discuss any matter not directly related to Korea since this lay outside the UNC province. When the Communists complained that the U.N. Command did not represent all the United Nations and that use of this term would be incorrect, Joy countered that the Chinese Volunteers did not represent the People's Republic of China either. He told Nam that the UNC was willing to drop all references to specific governments in the recommendations if the enemy so desired.23

Finally on 16 February, the Communists brought forth a revised proposal:

In order to insure the peaceful settlement of the Korean question, the military commanders of both sides hereby recommend to the government of the countries concerned on both sides that, within three (3) months after the Armistice Agreement is signed and becomes effective, a political conference of a higher level of both sides be held by representatives appointed respectively to settle through negotiation the questions of the withdrawal of all foreign forces from Korea, the peaceful settlement of the Korean question, etc.

With the understanding that "foreign" meant non-Korean forces and that "etc." did not pertain to matters outside of Korea, the U.N. Command accepted the Communist version in toto on 17 February.24

As Joy informed General Ridgway, the Communist statement afforded the wide latitude desired by the joint Chiefs of Staff and could be interpreted in almost any fashion since at best it was only a recommendation.25

It had only taken eleven days to reach an agreement on Item 5- by far the best record of all. Even the agenda had taken longer. Perhaps because of its very vagueness, both sides could easily accept such a noncommittal statement since in essence it settled nothing and promised little. If it later became inconvenient or unnecessary, it could be ignored. On the other hand, if both sides found it worth pursuing, a conference could be called. Regardless of the meaninglessness of Item 5, three items were now out of the way. But the discussion on Items 3 and 4 showed no signs of a imminent meeting of the minds and they were the most important of all.

The Horse Traders

Since the perplexing problem of airfields had been temporarily shelved, the staff officers on Item 3 were able to concentrate on the less troublesome details in late January. Cols. Don O. Darrow and Kinney of the Air Force and Lt. Col. Howard S. Levie of the Army had to cope with Colonel Chang of the North Korean Army and Col. Pu Shan of the Chinese Communist forces- all in all a very competent group of officers.

To get these informal talks under way, the UNC delegation had prepared a draft armistice covering all the topics to be considered under Item 3. Actually there were four main areas that the UNC staff officers hoped to settle: rotation; the number of ports to handle rotation and replenishment; the composition of the neutral nations' supervisory organ and inspection teams; and the control of coastal islands still in dispute. The draft armistice submitted by the U.N. Command provided a convenient point of departure for the staff conferences.

There was a refreshing atmosphere in the truce tent during the first meetings that followed. On the Communist side there was less haranguing and speechmaking; their staff officers had an air of serious intent to make progress. They were inclined to accept as much of the UNC wording as possible and their suggested changes were frequently regarded as improvements by the U.N. Command.26

Nevertheless, the Communists were not ready to surrender, despite their more businesslike approach. They opened the discussion of rotation by expressing great astonishment at the "enormous" figure of 75,000 per month proposed by the U.N. Command. It may be remembered that earlier they had offered to permit a monthly rotation of 5,000 and the U.N. Command had declared this would be totally insufficient. In the bargaining that followed, rotation and the number of ports that would be permitted to handle the flow of personnel and equipment were closely linked together. The Communist staff officers were disposed to place the UNC suggestion that twelve ports be used in North Korea and ten in South Korea in the same category as the 75,000 rotation figure.27

Gradually the differences between the two sides shrank. The enemy offered 25,000 for rotation and the U.N. Command lowered its figure to 40,000, provided that the Communists accepted eight ports of entry on each side. In a counterproposal, Colonel Chang put forward a total of 25,000, excluding personnel leaving or entering on rest and rehabilitation passes and those on temporary duty, but he insisted on limiting the number of ports to three for each side.28

At this point General Ridgway and his staff wanted to take a final position, holding fast to the 40,000 figure and reducing the number of ports to six. They believed that the enemy would give in if confronted with a firm offer. In Washington, however, the Department of Defense and State did not wish the negotiations to break down over such relatively minor issues, but they agreed to a stand at 40,000 and six ports per side provided there were no implied ultimatum.29

By mid-February the UNC requirements had decreased to seven ports and 40,000 men, while the enemy had expanded its proposals to four ports and 30,000 men. The dickering went on for another week and then the U.N. Command went down to 35,000 men and six ports and the Communists came up to 35,000 men and five ports per side.30

With only one port separating the two sides from agreement, General Ridgway gave Joy permission on 7 March to settle for five ports if and when he felt that it would encourage settlement of other problems. Ridgway was worried at that time about the growing indication that the Communists intended to use the neutral nation's inspection teams to examine classified equipment closely for the collection of technical intelligence. He felt that the wording of the armistice agreement must insure that this would not happen.31

This was a rather odd turnabout, since traditionally the Communists had opposed inspection and argued that good faith was enough. As Colonel Kinney pointed out to Chang in the staff officer meetings, the Communists had originally tried to apply restrictions on all activities of the inspection teams, but now were insisting upon the full rights of the teams to examine all equipment carefully.32 The aftermath to this switch on inspection laid the Communists' sincerity on the subject open to question, however, for when Kinney offered to settle for five ports if the enemy would give up detailed inspection, Chang quickly accepted on 15 March.33 Regardless of whether the Communists were using inspection solely for bargaining purposes or not, the matter of rotation and ports of entry were now agreed upon at 35,000 men per month and five ports of entry per side.34

Insofar as the question of coastal islands was concerned, the Communists proved to be particularly amenable. On 3 February they agreed to let the U.N. Command retain control over the five island groups under dispute on the west coast of Korea.35 The U.N. Command had expected a fight on this provision of the draft armistice, but the enemy had surprisingly decided not to contest it.36

There was some discussion on the topic of coastal waters which the U.N. Command had defined as comprising a distance of three miles from shore at mean low tide. The Communists were reluctant to go into the subject, since they felt that it did not matter what the distance might be, provided each side ceased naval blockade and patrol in its opponent's waters. When the UNC officers pressed for a 3-mile limit to prevent unintentional violations, the Communists came out in support of a 12-mile zone. This slowed the UNC eagerness to have a precise figure written into the armistice, for the United States preferred not to set a precedent by accepting a 12-mile definition of coastal waters in Korea. The upshot was that both sides took the matter under further consideration.37

Three of the four issues that the staff officers wished to settle had proved open to negotiation and bargaining, but the fourth- the composition of the neutral nations supervisory organ and inspection teams- soon developed into a bottleneck second only to the airfields dispute. It may be recalled that the original Communist suggestion that neutral nations serve on the supervisory organ had been general and vague. As General Lee had defined "neutral nation," the term meant a nation that had not participated in the fighting in Korea. He had indicated that Poland, Czechoslovakia, Switzerland, and Sweden would qualify under this description.38

When Ridgway had asked for guidance, his superiors responded quickly that as UNC choices, Sweden, Switzerland, and Norway would be acceptable if they would consent to serve. As for the possible Communist selections, there was no real difference among the satellites and any three would be agreed to. Under no circumstances, however, would the USSR be considered acceptable as a neutral nation, they warned.39 Here was the crux of the matter, for despite the fact that the Soviet Union had not formally intervened in the Korean War, the United States did not doubt that she was delivering both moral and physical sustenance to the Chinese and North Korean Communists. By no stretch of the imagination could the Russians be considered neutral in the estimation of the American military and political leaders, and they showed an early and fixed determination to deny them a neutral status. The trump card in the U.S. hand was the agreement with the Communists that the neutral nations must be acceptable to both sides. The power of the veto- long a favorite Russian weapon- might now be turned against the USSR.

Diplomatic approaches to Sweden, Switzerland, and Norway during December drew affirmative responses and Ridgway was authorized to nominate them as the UNC selections at an appropriate moment.40 The opportunity did not arise until 1 February when the U.N. Command submitted its choices in the staff officer meeting, but the Communists were in no hurry. Despite frequent reminders and proddings, it was not until the 16th that they named Poland, Czechoslovakia, and the USSR. The U.N. Command immediately accepted the first two and rejected the Soviet Union.41

Since Ridgway's superiors hoped that the Communists would not insist upon the inclusion of the USSR, they preferred to de-emphasize Russian participation in the war as the reason for the UNC rejection. Unless the enemy persisted, they favored giving no reason at all. If the enemy pressed for an explanation, the U.N. Command could fall back upon the proximity of the Soviet Union and its record of past participation in Korea as disqualifying factors.42

Ridgway and Joy agreed with the appraisal so far as it went, but warned that the staff officers suspected that the enemy might be trying to lay the groundwork for a trade of concessions on rotation and ports in return for acceptance of the Soviet Union. If this were true, then the U.N. Command would be better off telling the Communists unequivocally that the USSR would never be acceptable before the enemy involved its prestige.43 Not prepared to take this step until other possibilities had been exhausted, the Washington leaders told Ridgway that the U.N. Command might offer to drop Norway if the Communists would reciprocate on the Soviet Union.44

On 25 February the UNC staff officers followed through on these instructions, but Colonel Chang and his assistants refused to bargain. Their continued insistence upon the USSR convinced Ridgway that the U.N. Command must make a final stand on the issue. The JCS consulted with their colleagues at the Defense and State Department level and received Presidential approval to inform Ridgway that the United States was willing to have the UNC refusal to accept the USSR made "firm and irrevocable." Ridgway might proffer an alternative solution of the problem concomitantly with the rejection, if he thought agreement could be gained. They suggested that both sides select nations, regardless of their status in the Korean War, to man the supervisory organ and inspection teams. This would include the United States for the UNC side and the Communists could appoint the Soviet Union if they wished.46 Since this would divorce the Russians from a neutral designation, there was no objection to the Russians serving on frankly partisan organs.

When the Communists showed no interest in forming nonneutral groups to conduct supervision and inspection, the staff officers were forced to put the matter aside. Their earnest efforts had resulted in the solution of the rotation, port, and coastal island controversies, as well as the settlement of a number of lesser details on Item 3. By mid-March only differences over airfields and the Soviet Union remained outstanding.

As the negotiations ground to a standstill in both Item 3 and Item 4, Admiral Joy and staff took stock of the over-all truce situation and concluded that there were two promising methods of obtaining a satisfactory armistice from the enemy. The more drastic solution entailed the presentation of a complete armistice document incorporating some concessions to the enemy along with an ultimatum. Either the Communists would have to accept within a stated time limit or the negotiations would be terminated and hostilities resumed. Such a course would require a high-level decision and willingness to open up on the battlefield if the ultimatum were turned down, but Joy believed that it offered the best hope for a quick and favorable settlement.

The second choice would be the submission of a complete armistice document without the open ultimatum. The enemy delegates would be informed that this was the final UNC effort and only minor changes in wording would be considered. The plenary sessions would recess and the United Nations Command would decline to enter into further substantive discussions. Although there would be no breaking off of the negotiations, since the liaison officers would be available for consultation, the UNC position would not be altered nor any further concessions made.46

In brief, Joy and his associates advocated the threat of force or the combined use of the recess and an inflexible front on the major issues to produce an armistice. As Ridgway pointed out, both of the suggested courses were ultimatums; the chief difference was that the alternative course had no time limit. Either one would bring censure to the U.N. Command if the negotiations were

165broken off and this would be contrary to the JCS instructions. Despite the advantages in the Joy suggestions, Ridgway did not think that the time was ripe for the open or the implied ultimatum as yet.47

This was Ridgway vis-a-vis the UNC delegation, acting as a moderating influence and tempering the bolder and riskier proposals emanating from Panmunjom. On the other side of the coin was Ridgway, the theater commander, versus the Washington policy makers. Here was the more aggressive leader urging the adoption of a determined plan of action that would make the enemy realize that the U.N. Command would grant no more concessions. Just one day after he told Joy that he should continue the "present course of action" in the truce negotiations, he sent off a frank appraisal of the situation to the JCS.

Neither he nor his staff knew whether the Communists wanted an armistice or not, he told the joint Chiefs on 11 March, or how they really felt on the current issues. On the other hand, it was clear that the enemy attitude was becoming more arrogant and obdurate and that the position of the UNC delegates was deteriorating daily. To arrest this trend, the U.N. Command either had to take a public, hard and fast stand backed by official support from Washington and as many of the U.N. participants in Korea as possible or apply the one influence that the Communists evidently respected-force. Since the latter seemed to be out of the question, he strongly pressed for an open and flat rejection of the Soviet Union's membership on the neutral nations supervisory commission as a first step in attaining a final position.48

Army staff members in Washington supported the U.N. commander's argument for stiffening the Panmunjom front. However, G-3 questioned the advisability of approaching the issues on a piecemeal basis. Maj. Gen. Clyde D. Eddleman, the Deputy G-3, told the Chief of Staff that the impact would be far greater if the major unsolved problems were presented in a single package. Then if the Communists would not accept and the negotiations ended, the U.N. Command would be in a stronger position for having made an effort to break the deadlock. Secretary of State Acheson favored the idea of an over-all proposal, Eddleman added.49 So, too, did General Collins, his fellow joint Chiefs of Staff, the Secretary of Defense, and the President. But before a single package could be fashioned, they wanted the issues reduced to an absolute minimum. Then, when an impasse developed at the subdelegation level and Ridgway was prepared to segregate and reclassify the nonrepatriate prisoners, the U.N. commander would have the plenary conference assemble. Joy would deliver a letter from Ridgway to Kim and Peng urging a personal meeting of the commanders. If the Communists agreed, Ridgway would present the package on an all-ornothing basis. The U.N. Command would concede on airfields and the Communists would be expected to give in on forcible repatriation and the Soviet Union. Although there would be no substantive debate, the Washington proposal went on, the liaison officers would remain available and the UNC delegates would be willing to meet to explain their proposal.50

Ridgway must have been taken aback by the new proposal. He had just turned down a similar method of approach by Joy and then within a week to receive from his superiors a counterpart which he liked even less must have astonished him. In any event he recovered quickly and protested vigorously. A meeting of the field commanders would imply authority which he did not believe existed on the Communist side and would cause untold administrative delays. Moreover, the U.N. Command would be asking the enemy to concede on two issues while it yielded on a single one. As for the segregation and reclassification of POW's, he opposed any such action since it might jeopardize the lives of the prisoners in Communist hands. The Soviet Union he was extremely reluctant to accept on any terms, even on a frankly partisan commission. If a package were to be offered to the enemy, the U.N. Command should be given authority to indicate that refusal would mean termination of the negotiations in the UNC eyes. His own recommendations, he concluded, had not changed. First eliminate the Soviet Union controversy- then a package deal could be presented.51

The U.S. political and military leaders were willing to meet some of the objections Ridgway raised. If he did not want to confer with the Communist commanders, a plenary session of the delegates would serve. They had believed that Ridgway's presence would help underline the seriousness of the final proposal and the importance that the U.N. Command attached to it. Although they had seen no indication of an early solution to the USSR issue, they would be happy to have this solved before the package was offered. The essential factor here, they reminded Ridgway, was not Russian participation on the supervisory commission, but designation of the Soviet Union as a neutral nation. A compromise that avoided the latter would be perfectly acceptable.

With this out of the way, the Washington leaders got down to some cold facts. They did not want an ultimatum delivered openly or implied with the package proposal. Since the United States and its allies had little inclination to undertake increased military action to back an ultimatum, it could only be an empty gesture. If there were to be a break over the package offer, the blame must still fall upon the enemy.52

This was a frank admission by the JCS that neither the United States nor its fellow nations in Korea wanted a resumption of full-scale hostilities and had no intention of posing an idle threat that the Communists might challenge. Few actions could do more danger to the UNC cause politically than a bluff that the enemy called. After this message, talk of ultimatums dwindled. Ridgway continued to oppose the USSR's participation in any capacity, but, from this time on, he tended to support the concept of a package proposal as the best hope for an armistice.53

By the first of April, the staff officers had been in conference for over nine weeks. Despite the real progress they had made on the lesser problems and on many details of Item 3, the question of airfields and the Soviet Union still remained unsolved. So, on 3 April, the subdelegation reconvened, with General Harrison replacing Ferenbaugh as the Army member. The U.N. Command accepted Hsieh's suggestion that the agreements reached by the staff officers be confirmed, but this was the last accord. The arguments took up where they had left off and the meetings became shorter and shorter. At the 14 April session, a record time of fifteen seconds elapsed between the opening and closing of the meeting.54 With both sides refusing to budge an inch, the staff took over again on 20 April. In the meantime the discussions on prisoners of war had reached a new climax.

Screening the POW's

During February the staff officers had met twenty-two times to discuss Item 4. Despite their earnest efforts, the chief bone of contention- forced repatriation- still remained. Some of the details were cleared up, but the Communists were reluctant to settle subsidiary matters until the controlling principle was determined. In the face of the unwillingness of both sides to retreat further until all possibilities had been tried and exhausted, agreement was no nearer at the end of February than it had been a month earlier.

The subdelegations reconvened for a series of meetings during the first half of March with a similar lack of success. Admiral Libby pressed for the exchange of sick and wounded prisoners, for the delivery of POW packages, and for formation of joint Red Cross teams to visit the camps, but Maj. Gen. Lee Sang Cho would not consider a piecemeal approach to a settlement.55

Instead, Lee attacked the U.S. stand on "no forced repatriation," which he characterized as a verbal trick rather than a concession by the U.N. Command. He again charged that the United Nations Command intended to hand over the Chinese prisoners to the enemy of the Chinese people-Chiang Kai-shek. And in between his jousts with Libby on the main topic, Lee found the subject of the recent riots of prisoners on Koje-do rewarding. The outbreak of violence on 18 February at the UNC prisoner camps made good propaganda for the Communist delegate.56

In fact Lee became so enthusiastic in his work that Libby had to ask him not to scream at him. He was not deaf, the Admiral declared, and, besides, he did not understand Korean and much of the effect of the emotional delivery was lost in the translation.57

After two fruitless weeks of debate, the staff officers took up the task again. The shifting of problems back and forth between the subdelegation and staff officers during the January to April period was reminiscent of a caf? that had two orchestras so that there would be no interruption to the dancing. In this case, however, both combinations featured the same kind of music- discordant and cacophonous- making it impossible to dance.

In an effort to introduce a new note to the proceedings, General Ridgway decided to explore another line at the staff officer level in mid-March. It will be recalled that he had been given permission to remove prisoners who might forcibly resist repatriation because of their fear of the consequences from POW status. With this object in mind Ridgway now wanted to find out whether revised lists eliminating all in this category by overt screening might be acceptable to the Communists. The nonrepatriates could then be called special refugees or some such name and all the other prisoners would be exchanged. To screen the prisoners unilaterally and covertly, Ridgway and his staff felt, might gravely imperil the safe return or even the lives of the UNC prisoners in enemy custody, but the Communists might consent to an overt screening.58

His superiors were a little dubious, since they feared that the enemy might try to revise the lists of UNC prisoners downward if Ridgway attempted openly to prune the Communist rosters.59 On the contrary, Ridgway rebutted, the enemy would never accept a fait accompli brought about by secret and unilateral action. Only by allaying Communist suspicion of UNC double-dealing could the United Nations Command protect itself against retaliatory measures. He and his staff thought that the enemy might agree to a trial screening.60

In the staff officer meetings there were increasing signs that the Communists were shifting their ground. They hinted on 22 March that there might be cases among the prisoners that could be given special consideration before the present lists were checked. And they also intimated that the initiation of closed, executive sessions might promote freer conversation. The UNC officers quickly followed up by proposing executive meetings until one side or the other desired to revert to the open conference again and the Communists agreed.61

This marked a definite turn for the better, but the enemy soon demonstrated that they would give "special consideration" only to the prisoners who had been former residents of the Republic of Korea. In no case would North Koreans or Chinese be placed in special categories, they insisted. Their hatred of Chiang and fear that the Chinese would be sent to Taiwan if they were not repatriated came through again and again during the staff sessions in late March.62

One of the major weaknesses of the UNC proposals on revising the POW lists was the fact that the UNC staff had no idea as to just how many prisoners would refuse repatriation. Based on guesswork, General Hickey, UNC chief of staff, estimated that of the 132,000 military prisoners, about 28,000 would prefer not to go home, but probably only 16,000 would resist repatriation. And of the 37,000 civilian internees, 30,000 would elect not to return and 2,000 would put up a fight to prevent going back. He thought that over half of the 20,000 Chinese prisoners would use every means at their disposal to present a solid block of opposition since they were well organized, disciplined, and controlled by strong leaders with Nationalist sympathies.63

Early in April, Colonel Hickman, UNC staff officer, told his counterpart, Colonel Tsai, that the U.N. Command was reluctant to take a poll to form a rough estimate of the number of military repatriates, but about 116,000 might be involved in an exchange.64 The figure of 116,000 tallied with the estimate of General Hickey which was admittedly a guess, but it evidently intrigued the Communists. It also may have been a tactical error on the part of the U.N. Command, for it misled the enemy into thinking that they would recover approximately that number of prisoners. At any rate, Colonel Tsai suggested on 2 April that both sides immediately check their lists and defer the debate on principles until this was completed. The Communists showed a desire to get a round figure of those who would forcibly resist repatriation in the obvious hope that the number would be no more than around 16,000. Two days later Hickman agreed and asked if the Communists would issue an amnesty statement before the screening to reassure the prisoners that they would not be punished when they returned. Although the enemy officers protested that such a statement would be unnecessary since the Communists desired nothing more than to return the prisoners to a peaceful life, they lost little time in providing the U.N. Command with a florid amnesty declaration on 6 April. This statement was given wide publicity throughout all the prisoner camps before the screening to encourage as many prisoners as possible to go home.65

The insistence of the Communists upon a round figure implied their tacit assent to the screening process and removed most of the previous objections to revising the prisoner lists. After Ridgway had conferred with Joy at Munsan-ni, he submitted his plan to carry out the interviewing and segregating of the POW's. The screening and separation of repatriates from nonrepatriates would be a one-shot operation, he told the JCS, and no one would be allowed to change his mind once he had made his choice. The Communists would expect to receive whatever number was announced by the U.N. Command, he went on, so no downward revisions could be made after the enemy was informed. In his opinion, screening was inevitable sooner or later and the quicker it was done the better. He frankly admitted that an explosive situation existed in the POW camps and the U.N. Command did not have the capability on hand to break up the camps into small dispersed units to reduce the danger.

Once the screening was finished, Ridgway intended to give the totals to the enemy, reclassifying the nonrepatriates and ROK residents who did not want to go to North Korea into a status other than POW. If the Communists accepted these figures, he would follow up by an effort to trade airfield restrictions for the dropping of USSR, thus completing the armistice. If the enemy did not accept the figures, Ridgway would present a package proposal with the same objectives on which the U.N. Command would stand firm.66

Permission was received on 3 April to start the screening at once and two days later Ridgway ordered Van Fleet to initiate Plan SCATTER.67 This plan was openly designed to make the maximum number of POW's available for repatriation. All were cautioned beforehand not to discuss the choice they had made with other prisoners prior to the interview lest they be subjected to violence and injury to force a change of mind. The final nature of the decision was strongly stressed to make each man think it over carefully. As each prisoner approached the interview area, he carried his clothing and equipment with him, so that there would be no need to return to his former enclosure if he chose not to return. In the interview that followed the unarmed interrogating officer or clerk related the disadvantages of refusal and the uncertainties that would face the nonrepatriates. He also warned the prisoner of the fate that might befall his family if he did not return. Then the prisoner was told again of the Communist amnesty that had been offered and asked a series of seven questions: 1. Will you voluntarily be repatriated to North Korea (China)? 2. Would you forcibly resist repatriation? 3. Have you carefully considered the impact of such action on your family? 4. Do you realize that you may remain here at Koje-do long after those electing repatriation have been returned home? 5. Do you realize that the UNC cannot promise that you will be sent to any certain place? 6. Are you still determined that you would violently resist repatriation? 7. What would you do if you were repatriated in spite of this decision? If at any point the POW indicated that he would accept repatriation, the questions ceased. On the other hand, if he mentioned suicide, fight to the death, escape, etc., the POW was segregated and put in a new compound.68

On 8 April Van Fleet began the screening. For the most part it proceeded smoothly and the separation of the nonrepatriates from those who wanted to return was accomplished without serious incident. But there were seven compounds containing over 37,000 determined North Korean Communists who would not permit the UNC teams to screen them. In one of these compounds, an altercation between the prisoners and ROK guards erupted into stone throwing and then to the use of machine gun fire. Before the fighting could be stopped, there were seven dead and sixtyfive other casualties.69

Despite the opposition of the ardent Communist elements, the results of the first three days of screening were amazing even to the U.N. Command. With approximately half of the 132,000 interviews completed, over 40,000 prisoners had declared that they would forcibly resist repatriation.70 It was a surprising demonstration of the strength of feeling among the POW's that must have been heartening to the psychological warfare experts, but it immediately cast a pall over the prospects for an armistice. Even were all the unscreened prisoners to return, the total would bear little resemblance to the 116,000 the Communists anticipated.

In the days that followed the U.N. Command made no attempt to screen the seven recalcitrant compounds and automatically put the prisoners in these enclosures among the repatriates. The remainder of the POW's and civilian internees were sent through the interviews, and by 15 April Ridgway was able to provide the JCS with the "round" figure the Communists desired. Of the over 170,000 military and civilian prisoners in UNC hands, only about 70,000 would return to the Communists without the use of force, he told the joint Chiefs. Since he realized that the enemy was not going to be happy about these figures, Ridgway proposed to permit either an international neutral body or joint Red Cross teams to rescreen all of the nonrepatriates if the Communists so desired. If they turned this suggestion down, then the UNC delegation would move back into plenary sessions and would present the package proposal.71 Although the 70,000 figure was by no means final, the JCS agreed that the U.N. Command should convey it to the enemy right away rather than risk a leak to the press. At the meeting of the staff officers on 19 April Colonel Hickman calmly informed Tsai that 7,200 civilian internees, 3,800 ROK prisoners, 53,900 North Koreans, and 5,100 Chinese- a total of 70,000 men- would be available for repatriation. The effect was dramatic! For once Tsai was speechless, overcome with emotion. When he finally recovered himself enough to talk, he quickly requested a recess ostensibly to study the figures.72 The evident shock to Tsai intimated that the Communists were completely unprepared for such a low estimate and the immediate recess was probably necessary not only for him to regain his composure but also to get new instructions from his superiors.

The tenor of these instructions was crystal clear the following day. The Communists felt that they had been deliberately deceived by the UNC's earlier estimate of 116,000 and Tsai mounted a full-scale assault upon the 70,000 figure. It was "completely impossible for us to consider," he cried, and "you flagrantly repudiated what you said before." In a counterblast, Hickman charged that the U.N. Command had felt the same sort of dismay when they had been given the 11,559-prisoner figure by the Communists in December. The UNC had conducted the screening in the fairest way possible and the percentage of prisoners that the Communists would get back was far greater than the 20 percent that the 12,000 UNC prisoners represented.73

Through the wrangling that ensued during the next few days, one fact stood out. The Communists had been stung once by the screening procedure and they would have nothing more to do with it. They repulsed the offers to permit rescreening by neutral or Red Cross teams summarily and insisted that the U.N. Command come up with a more favorable figure.74 The screening process which momentarily seemed to be a way to break the deadlock had merely resulted in increasing it. In justice to the U.N. Command, they had acted in good faith. Regrettably they had given the enemy a rough initial estimate based on what turned out to be incomplete and inaccurate information. During the interviews the UNC teams had sought to discourage the nonrepatriates as much as possible and encourage the POW's to go home. On the other side, it is not difficult to understand the attitude of the Communists and their feeling that they had been duped and led into a propaganda trap. Their natural suspicion of the motives of the U.N. Command needed little impetus to assume the worst.

The Package Is Delivered

The violent Communist opposition to the results of the UNC screening delimited the course of events at Panmunjom. If the POW issue could have been settled, Ridgway could probably have exchanged the airfield rehabilitation concession for the exclusion of Soviet Union and completed the armistice. Rejection of the no forced repatriation concept meant that a package proposal would have to include three issues and that one side would have to give way on two points. This complicated the matter since it introduced a sense of imbalance allowing an apparent advantage to the side that secured the two concessions. Under the circumstances it might well have been better to have had a fourth issue, real or manufactured, which the U.N. Command could have used to sweeten the pill that they now wanted the enemy to swallow.

While the enemy was launching its broadsides at the screening procedure, Ridgway made his final arrangements for presenting the package deal. He planned to support the UNC offer with a strong statement that might convince the Communists that this was the final position for the United Nations Command. Either the enemy must accept the whole package without debate or the responsibility for continued hostilities would rest on its shoulders. To bolster his stand, Ridgway asked that public statements along this line be made by the U.S. Government and other U.N. participants.75

Ridgway's superiors, however, were not willing to go quite so far. As long as the truce meetings remained in executive session, public statements were not possible, they pointed out. In the second place, they did not want Ridgway or the U.S. Government to make statements that could be interpreted as ultimatums. Uncompromising declarations might decrease the probability of Communist acceptance of the package and raise domestic and international expectations of quick military action if the enemy did not accept the proposal. In any case they moderated Ridgway's approach to eliminate the implication of an ultimatum.76 At the same time, the JCS and its staff worked diligently with the political advisors to fashion a statement that President Truman could release to support the UNC position.77

Judging from the actions of the Communists at the staff officer level, the executive meetings were about to end. On 24 April Colonel Tsai threatened to return to open meetings and the following day he carried out the threat. The Communists immediately issued a long resume of the April developments and the U.N. Command countered with a release setting forth its own version. As the debate moved out into the open again, Colonel Hickman requested a recess so that the UNC could make the last-minute arrangements for the formal delivery of its offer.78

General Ridgway and Admiral Joy were not concerned at this point whether the sessions were secret or open. In their opinion there was little need for secrecy since the separate elements of the package deal had been fully publicized in the press.79 But the military and political leaders in Washington disagreed. The open sessions generated more heat than light, they maintained, and they therefore preferred an executive meeting of the plenary conference. Then if the Communists disregarded the understanding to gain the propaganda initiative or if they turned down the suggestion for the executive meetings, the onus for failure to reach agreement in the negotiations would fall upon the enemy.80

Through the liaison officers the plenary conference was set up for April 28. When the delegates met, Admiral Joy requested an executive session and after a recess, the Communists agreed.81 Joy then went over the outstanding issues carefully and set forth the UNC solution which had been incorporated into a complete draft of the armistice. All mention of the rehabilitation of airfields, had been deleted and the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission was to be formed of Switzerland, Sweden, Poland, and Czechoslovakia. The paragraph referring to the disposition of POW's read as follows:

All prisoners of war held in the custody of each side at the time this Armistice Agreement becomes effective shall be released and repatriated as soon as possible. The release and repatriation of such prisoners of war shall be effected in conformity with lists which have been exchanged and have been checked by the respective sides prior to the signing of this Armistice Agreement.82

In effect this meant that the U.N. Command would swap the 70,000 repatriates that it held for the 12,000 in enemy custody, since it intended to reclassify the nonrepatriates into a status other than POW in the meantime.

The package proposal created as much stir as a pebble dropped into the ocean. Nam simply stated that "our side fails to see how your proposal of this morning can really be of help to the overall settlement of the remaining issues" and then called for an indefinite recess.83 Under the circumstances the Communists reaction was not surprising. The UNC offer had revealed nothing that the enemy had not anticipated as a result of discussions in the U.S. and U.N. press before the presentation. If it accomplished anything, it did reduce the number of issues to one- the number of POW's who would be repatriated. The other two soon canceled each other out, but as long as there remained such a wide discrepancy between the 70,000 figure that the U.N. Command had offered and the 116,000 the Communists expected, hopes for an early armistice would be small.

Yet despite the indifferent reception that the enemy had given the package proposal, this was a key moment in the negotiations. The UNC had officially fallen back upon its "final and irrevocable" position and the period of debate was over. There had been no ultimatum or threat of increased activity at the front, but the U.N. Command had passed the crossroads and embarked upon a firm course. Patience and firmness- the old standbys- were to be the chief weapons in the battles that lay ahead rather than force. In the meantime the battle at the front would go on as it had all winter, essentially a defensive war on both sides. Fought within carefully defined boundaries and under tacit rules, the war of the active defense nonetheless continued and took its daily toll of casualties.

Notes

1 Ferenbaugh had served with the Operations Division of the General Staff and as an assistant division commander of the 83d Division in World War II. In January 1951 he had taken over as commander of the 7th Division in Korea. Ferenbaugh's experience with political affairs during his tenure on the General Staff provided him with a good background for handling the negotiations.

2 Transcripts of Proceedings, Sixteenth and Seventeenth Sessions, Subdelegation Mtgs on item 3, 19-20 Dec 51, in FEC Transcripts, item 3, vol. II.

3 Ibid., Seventeenth and Eighteenth Sessions, 20 and 22 Dec 51.

4 Ibid., Twenty-fifth and Twenty-ninth Sessions, 29 Dec 51 and 2 Jan 52.

5 Joy, How Communists Negotiate, pp. 123-24.

6 See Chapter VI, above.

7 Msg, C 60961 Ridgway to DA, 7 Jan 52, DA-IN 17600.

8 Msgs, JCS 91600, and JCS 91606 to CINCFE, 10 Jan 52.

9 Msg, C 61348, Ridgway to JCS, 13 Jan 52, DA-IN 19740.

10 Transcript of Proceedings, Thirty-fifth Session, Subdelegation Mtg on item 5, 8 Jan 52, in FEC Subdelegation Mtgs on item 3, 8 Jan-19 Apr 52, Vol. III (hereafter cited as FEC Transcripts, item 3, vol. III).

11 Ibid., Thirty-sixth Session, 9 Jan 52.

12 Ibid., Thirty-seventh through Forty-fifth Sessions, 10 Jan-18 Jan 52. During the 18 January meeting, Hsieh became quite profane again, but the U.N.C delegates had come to realize that his bark was worse than his bite and paid little heed.

13 Ibid., Forty-sixth and Fifty-first Sessions, 14 Jan and 24 Jan 52

14 (1) Msg, C 62064, Ridgway to Collins, 23 Jan 52, DA-IN 3851. (2) Transcripts of Proceedings, Fifty-second and Fifty-fourth Sessions, Subdelegation Mtgs on item 3, 25 and 27 Jan 52, in FEC Transcripts, item 3, vol. III.

15 Msg, CINCUNC to CINCUNC (Adv), 5 Dec 51, DA-IN 8008.

16 Msg, JCS 90083, JCS to CINCFE, 19 Dec 51.

17 Msg, JCS 90388, JCS to CINCFE, 24 Dec 51.

18 Msg, CX 62465, Ridgway to JCS, 30 Jan 52, DA-IN 6207.

19 Msg, JCS 900075, JCS to CINCFE, 1 Feb 52.

20 General Harrison was the deputy commander of the Eighth Army. He had served in the Operations Division of the General Staff and as assistant division commander of the 30th Division during World War II and on the staff of the Supreme Commander, Allied Powers, in the postwar period. General Yu was Vice Chief of Staff of the ROK Army.

21 Transcript of Proceedings, Thirty-sixth Session, Mtgs on the Mil Armistice Conf, 6 Feb 52, in FEC Transcripts, Plenary Conf, vol. III.

22 Ibid., Thirty-seventh Session, 9 Feb 52.

23 Ibid., Thirty-eighth through Fortieth Session, 9-12 Feb 52.

24 Ibid., Forty-first and Forty-second Sessions, 16-17 Feb 52.

25 Msg, HNC 924, Joy to CINCUNC, 16 Feb 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Feb 52, an. 1, case 58.

26 Hq UNC/FEC, Korean Armistice Negotiations (Jul 51-May 52), vol. 2, ch. II, p. 58.

27 The North Korean ports included: Sinuiju, Manp'ojin, Hyesanjin, Hoeryong, Ch'ongjin, Sinanju, Hamhung, P'yongyang, Wonsan, Pyoktong, Songjin, and Haeju. The ports in South Korea were: Seoul, Yangyang, Ch'ungju, Taejon, Andong, Chonju, Taegu, Wonju, Sunch'on, and Pusan. See First Mtg of Staff Officers on Details of Agreement of Agenda item 3, 27 Jan 52, in G-3 Mtgs of Staff Officers . . . on item 3, bk. I.

28 Seventh through Eleventh Mtgs of Staff Officers . . . on item 3, 3-7 Feb 52, in G-3 Mtgs of Staff Officers . . . on item 3, bk. I.

29 (1) Msg, CX 63438, Ridgway to JCS, 12 Feb 52, DA-IN 104463. (2) Msg, JCS 901022, JCS to CINCFE, 13 Feb 52.

30 Fourteenth through Twenty-seventh Mtg of Staff Officers . . . on item 3, 10-23 Feb 52, in G-3 Mtgs of Staff Officers . . . on item 3, bk. II.

31 Memo, Ridgway for Joy, 7 Mar 52, sub: Armistice Negotiations, in FEC SGS Corresp File, 1 Jan-31 Dec 52.

32 Forty-sixth Mtg of Staff Officers . . . on item 3, 13 Mar 52, in G-3 Mtgs of Staff Officers . . . on item 3, bk. III.

33 Forty-eighth and Forty-ninth Mtgs of Staff Officers . . . on item 3, 15-16 Mar 52, in G-3 Mtgs of Staff Officers . . . on item 3, bk. III.

34 The final list of ports included: Sinuiju, Ch'ongjin, Hungnam (for Hamhung), Manp'ojin and Sinanju in North Korea and Inch'on (for Seoul), Taegu, Pusan, Kangnung (instead of Yangyang) and Kunsan (for Chonju) in South Korea.

35 These were Paengnyong-do, Paechong-do, Soch'ong-do, K'unyonp'yong-do, and U-do-all located below the 38th Parallel.

36 Seventh Mtg of Staff Officers . . . on item 3, 3 Feb 52, in G-3 Mtgs of Staff Officers . . . on item 3, bk. I.

37 Hq UNC/FEC, Korean Armistice Negotiations (Jul 51-May 52), vol. 2, ch. II, pp. 64-65.

38 Transcript of Proceedings, Second Session, Subdelegation Mtgs on item 3, 5 Dec 51, in FEC Transcripts, item 3, vol. I.

39 (1) Msg, C 59130, CINCFE to JCS, 11 Dec 51, DA-IN 8556. (2) Msg, JCS 89473, JCS to CINCFE, 12 Dec 51. This message was approved by the JCS,

State and Defense Departments, and the President.

40 Msg, JCS 90381, JCS to CINCFE, 24 Dec 51, DA-OUT 90381. Army and State Departments approved this message.

41 Twentieth Mtg of the Staff Officers . . . on item 5, 16 Feb 52, in G-3 Mtgs of Staff Officers . . . on item 3, bk. II.

42 Msg, DA 901353, G-3 to CINCFE, 17 Feb 52.

43 (1) Msg, C 68918, Ridgway to JCS, 19 Feb 52, DA-IN 107012. (2) Msg, C 63918, Ridgway to JCS, 19 Feb 52, DA-IN 107018.

44 (1) Msg, JCS 901451, JCS to CINCFE, 19 Feb 52. (2) Msg, DA 901845, CofS to CINCFE, 28 Feb 52. Norway was selected since it had supported the U.N. action in Korea.

45 (1) Msg, CX 64842, Ridgway to JCS, 27 Feb 52, DA-IN 109768. (2) Msg, JCS 902160, JCS to CINCFE, 27 Feb 52.

46 Msg, HNC 1027, Joy to CINCUNC, 9 Mar 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Mar 52, an. 1, CofS, incl 27.

47 Msg, C 65020, CINCFE to CINCUNC (Adv), to Mar 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Mar 52, an. 1, incl 28.

48 Msg, HNC 1033, Ridgway to JCS, 11 Mar 52, DA-IN 114495.

49 Memo, Eddleman for CofS, 11 Mar 52, sub: Courses of Action in the Korean Armistice Negotiations, in G-3 091 Korea, 3/7.

50 Msg, JCS 903687, JCS to CINCFE, 15 Mar 52.

51 Msg, C 65430, CINCFE to JCS, 17 Mar 52, DA-IN 116955.

52 Msg, JCS 904101, JCS to CINCFE, 19 Mar 52.

53 Msg, C 65650, Ridgway to JCS, 20 Mar 52, DA-IN 118696.

54 Transcripts of Proceedings, Fifty-fifth through Sixty-sixth Sessions, Subdelegation on item 3, 3-14 Apr 52, in FEC Transcripts of Proceedings, Subdelegation on item 3, vol. III, 8 Jan-19 Apr 52.

55 Ibid., Fifty-sixth through Fifty-eighth Sessions, Subdelegation on item 4, 29 Feb-2 Mar 52, in FEC Subdelegates Mtgs on item 4, vol. IV, 28 Jan-7 Mar 52.

56 For more detail on this riot, see Chapter XI, below.

57 Ibid., Fifty-ninth and Sixtieth Sessions, 3-4 Mar 52.

58 Msg, CX 65424, Ridgway to JCS, 17 Mar 52, DA-IN 116952.

59 Msg, JCS 904101 JCS to CINCFE, 19 Mar 52.

60 Msg, C 65650, Ridgway to JCS, 20 Mar 52, DA-IN 118696.

61 Twenty-ninth and Thirtieth Mtgs of Staff Officers on Details of Agreements on item 4, 22-23 Mar 52, in G-3 Mtgs of Staff Officers . . . on item 4.

62 Thirty-sixth Mtg of Staff Officers on Details . . . on item 4, 29 Mar 52, in G-3 Mtgs of Staff Officers . . . on item 4.

63 Memo, Hickey for Hull, no date, no sub, in G-3 383.6, 5/1. This memo dates approximately in mid-February 1952.

64 Thirty-ninth Mtg of Staff Officers on Details . . . on item 4, 1 Apr 52, in G-3 Mtgs of Staff Officers . . . on item 4.

65 (1) Fortieth, Forty-first Mtgs of Staff Officers on Details . . . on item 4, 2 and 4 Apr 52. (2) Msg, Tsai to Hickman, 6 Apr 52. Both in G-3 Mtgs of Staff Officers . . . on item 4.

66 Msg, HNC 1118, Ridgway to JCS, 3 Apr 52, DA-IN 123736.

67 (1) Msg, JCS 905426, JCS to CINCFE, 3 Apr 52. (2) Mg, CX 66469, Ridgway to JCS, 5 Apr 52, DA-IN 124553.

68 (1) Msg, C 66649, Ridgway to G-3, 10 Apr 52, DA-IN 126222. (2) Msg, C 67178, Ridgway to G-3, 19 Apr 52, DA-IN 129608.

69 (1) Msg, C 66761, Ridgway to G-3, 11 Apr 52, DA-IN 126801. (2) Msg, C 66838, Ridgway to G-3, 12 Apr 52, DA-IN 127294. Casualties included: 4 ROK dead, 4 wounded, 1 U.S. lieutenant wounded; 3 North Korean dead, 60 wounded. See below, Chapter XI, for further details on prisoners' refusal to be screened.

70 Msg, CX 66754, CINCUNC to G-3, 11 Apr 52, DA-IN 126732.

71 Msg, CX 66953, Ridgway to JCS, 15 Apr 52, DA-IN 128107.

72 Forty-second Mtg of Staff Officers on Details . . . on item 4, 19 Apr 52, in G-3 Mtgs of Staff Officers on . . . item 4.

73 Forty-third Mtg of the Staff Officers . . . on item 4, 20 Apr 52, in G-3 Mtgs of Staff Officers . . . item 4. Hickman later said that his counterattack actually caused Tsai to blush for the first and only time during the meetings. Interv, author with Maj Gen George W. Hickman, Jr., 7 Mar 58. In OCMH.

74 Forty-fourth through Forty-sixth Mtgs of the Staff Officers . . . on item 4, 21-23 Apr 52, in G-3 Mtgs of Staff Officers . . . on item 4.

75 Msg, CX 67235, Ridgway to JCS, 20 Apr 52, DA-IN 129944.

76 Msg, JCS 906923, JCS to CINCFE, 22 Apr 52. This message was drafted by State and approved by the services, Defense Department, and the President.

77 Msg, JCS 907375, JCS to CINCFE, 26 Apr 52.

78 Hq UNC/FEC, Korean Armistice Negotiations (Jul 51-May 52), vol. 2, ch. III, pp. 97-98.

79 Msg, C 67640, Ridgway to JCS, 27 Apr 52, DA-IN 132562.

80 Msg, JCS 907378, JCS to CINCFE, 27 Apr 52.

81 Besides Admiral Joy, the UNC delegation now consisted of Harrison, Turner, Libby, and Yu. The Communists were represented by Nam, Hsieh, Lee, General Pien Chang-wu, and Rear Adm. Kim Won Mu, who had replaced Maj. Gen. Chung Tu Hwan.

82 Transcript of Proceedings, Forty-fourth Session, 28 Apr 52, in FEC Transcripts of Proceedings, Msgs on the Mil Armistice Conf, vol. IV, 28 Apr-3 Jun 52.

83 Ibid.

Causes of the Korean Tragedy ... Failure of Leadership, Intelligence and Preparation