History  On Line

On Line

After the United Nations Command had halted the enemy offensive in the spring of 1951, there had been no effort by the Eighth Army to launch a counterattack. It was not that General Van Fleet's forces lacked the capability to force the enemy to withdraw "far north" of the 38th Parallel, but the question was "how far to push in order to accomplish the greatest damage." Any advance north of the Parallel would shorten the supply and communications lines of the Communists and correspondingly increase those of the Eighth Army. The tasks of reconstituting the destroyed transport facilities in North Korea and of assuming civil affairs functions in that desolated area would also be considerable. Most important of all, Van Fleet had to keep in mind two overriding factors: he did not have sufficient forces to destroy the enemy by maneuver and encirclement; and he could not advance beyond the KANSAS-WYOMING defense lines that straddled the 38th Parallel without the express permission of the JCS and General Ridgway.1 In view of these restricting elements and the reluctance of the majority of the nations composing the U.N. Command to advance again toward the Yalu, it was hardly surprising that in June 1951 Van Fleet concluded: "Continued pursuit of the enemy was neither practical nor expedient. The most profitable employment for the Eighth Army, therefore, was to establish a defense line on the nearest commanding terrain north of Parallel 38, and from there to push forward in a limited advance to accomplish the maximum destruction to the enemy consistent with minimum danger to the integrity of the Eighth Army."2

The decision to strengthen the defensive lines of the Eighth Army and to confine offensive action at the front to limited advances marked the end of the fluid phase of the Korean War and the start of the new war.

The KANSAS-WYOMING Line

Line KANSAS, the defense line selected by Van Fleet, began near the mouth of the Imjin River twenty miles north of Seoul and snaked its way to the northeast on the south side of the river through low barren elevations which gradually gave way to higher, moderately wooded hills. (Map I) Where the Imjin crossed the 38th Parallel, KANSAS veered eastward and upward toward the Hwach'on Reservoir and then angled northeastward again across the steep, forested South Taebaek Mountains until it reached the east coast some twentyfive miles north of the 38th Parallel. The terrain from the Hwach'on Reservoir to the east coast was particularly rugged. The mountain slopes rose sharply, especially on the west and south faces, and good roads were almost nonexistent. The defensive strength of KANSAS was increased by full use of the dominating terrain and the numerous water barriers along the route.

Guarding the approaches to KANSAS on the western front, Line WYOMING looped northeastward from the mouth of the Imjin towards Ch'orwon, swung east to Kumhwa, and then fell off to the southeast until it rejoined KANSAS near the Hwach'on Reservoir. In the spring of 1951 it served as an outpost line screening KANSAS.

Although Line KANSAS permitted the enemy to retain control of the communication complex of the area called the Iron Triangle (Ch'orwon-Kumhwa-P'yonggang), Van Fleet felt that the line afforded the UNC forces the advantages of a defensible terrain, a satisfactory road and railroad net, and logistic support. In the event of a cease-fire he recommended in early June that the Eighth Army be at least ten miles in advance of Line KANSAS in case a 10-mile withdrawal by both sides to form a buffer zone be made part of the terms. For planning purposes Ridgway agreed.3

In the meantime, Van Fleet instructed his corps commanders to fortify Line KANSAS in depth and to build hasty field fortifications along the advance Line WYOMING t0 delay and blunt the force of enemy assaults before they reached KANSAS. On the eastern end of the front, the U.S. X and ROK I Corps would establish patrol bases ahead of the main line of resistance to maintain contact with the enemy. To prevent enemy agents from posing as peasants in order to gather intelligence, Van Fleet told his commanders to clear the battle area of all Korean civilians, who were to be evacuated to the rear.4

Since the terrain became more mountainous in the east and was served by a poor communications network, Van Fleet had deployed his four corps accordingly, with the ROK I Corps forming the eastern anchor, flanked by the U.S. X Corps in the east central sector, the U.S. IX Corps in the west central area, and the U.S. I Corps defending the broadest sector on the west. The first three corps fronts were narrower because of the rugged mountains and lack of good roads. Most of the ROK divisions were placed where the least logistical support could be provided since they required less to live on and fewer auxiliary units.5

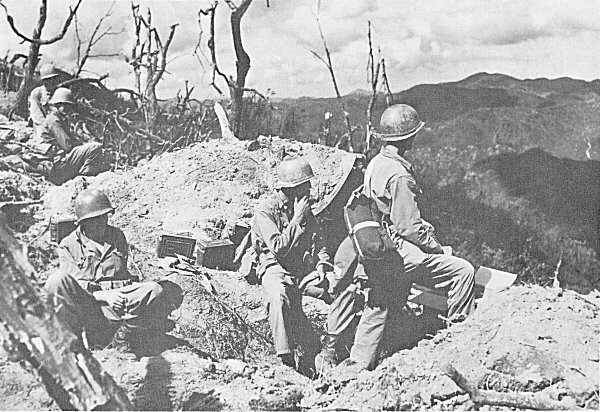

By 1 July the main fortifications of Line KANSAS were nearly complete. To expedite the work, Van Fleet had sent three South Korean National Guard divisions forward to serve as labor troops, one to each U.S. corps. The log-and-sandbag bunkers, and deep, narrow trenches along the KANSAS line resembled World War I entrenchments. Bunkers, usually adjoining and forward of lateral trenches, housed automatic rifles and machine guns. Most of the bunkers were dug into hillsides or saddles on the military crests with the larger ones on the higher hills serving as forward command and observation posts.

Known as "hootchies" in the Army vernacular, the bunkers were usually built with solid overhead cover and separate living quarters behind the battle stations. Each reflected the ingenuity of its occupants in providing the comforts of home, such as cots, flooring, and furniture.

Along the lateral trenches, the riflemen and rocket-launching crews notched revetted bays for firing their weapons and slightly behind them recoilless rifle emplacements were dug in and revetted with sandbags. In defilade on the reverse slope of the hills, protected mortar firing positions were constructed and roads were cut to permit tanks to move up and fire from parapeted front-line positions. Camouflage nets and shubbery were used extensively to conceal the bunkers and prepared positions.

To delay enemy offensives barbed wire fences were laid out and mines were planted in patterns that would funnel attackers into the heaviest defense fires. In the U.S. I and IX Corps sectors, where WYOMING positions were occupied rather than KANSAS, the troops plotted mine fields and dug the holes, then stored the mines nearby to be buried when and if a retreat from Line WYOMING should prove necessary.6

Structural weaknesses soon appeared in many of the hasty fortifications. Bunker roofs collapsed when an inadequate number of supporting timbers were used and the heavy July rains caved in a number of bunkers built in terrain where erosion was swift. These were relocated and rebuilt. Inspection and experience revealed other defects in the defense line. When shubbery was allowed to wither, it clearly delineated the emplacement positions and wellbeaten paths in front of the bunkers had the same effect. Indiscriminate clearing of trees and shrubs in front of firing positions also disclosed the defense line. In some sectors improper placing of barbed wire restricted the fields of fire and tactical wire strung too close to front-line positions permitted the enemy to toss hand grenades into the trench area. But most of the deficiencies had been corrected by the end of July and Line KANSAS was considered strong enough to stop anything less than a full-scale enemy offensive.

Instead of the usual general and combat outpost system, Eighth Army organized its outposts as a series of patrol bases.7 Developed initially by front-line units across the army front while reserve troops strengthened defense positions, patrol bases afforded depth to the defense line. They were established up to ten miles in front of the main battle line on commanding terrain and in most cases were not mutually supporting.

They were later manned by reserve troops, usually a reinforced company, for distances up to 2,000 yards and by a battalion or regiment at the more advanced bases. Operating within range of their supporting medium artillery, patrol base commanders could maintain contact with the enemy, determine enemy dispositions by vigorous patrolling, capture enemy prisoners, and provide warning of attack by absorbing the first assaults. Trip flares, mines, barbed wire, planned fields of fire, as well as extra ammunition and firepower, made the patrol base a difficult position to penetrate. The bases were often subjected to the favorite Chinese and North Korean tactic-the night attack- but they were harder to infiltrate than outpost lines and units could withdraw intact to the main line of resistance in the event of a major offensive.8

The patrol base system and the lull in operations during July caused by the armistice negotiations gave the Eighth Army time to improve the defenses of Line WYOMING, too. General Van Fleet decided to add depth to his defenses by making WYOMING a permanent line and on 30 July he told his corps commanders that it would be regarded as the main line of resistance. Only in the event of heavy losses would the Eighth Army withdraw to Line KANSAS to launch its counterattack.9

By midsummer the pattern was set. The Eighth Army had established its defensive positions and was prepared either to conduct local offensive operations or to punish any attempt by the enemy to penetrate the KANSAS-WYOMING lines.

The Enemy

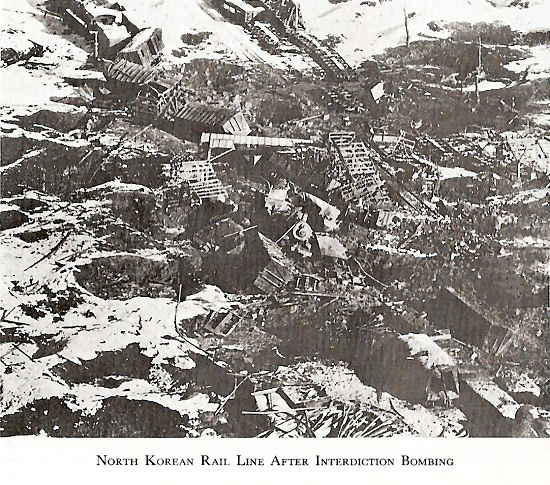

Despite the steady build-up of Communist forces during June and July, the expected offensive was not launched. Instead the enemy continued to bring up supplies by rail and road and to strengthen his defensive positions. Since casualties were light on both sides during the early summer slowdown in the fighting and the Communists maintained a high flow of replacements, their offensive capability mounted.10

On 1 July the Communist forces in Korea totaled 459,200 men, according to Eighth Army intelligence estimates. Of these 248,100 were Chinese and the remainder North Korean. In addition, there were 7,500 North Korean guerrillas operating in South Korea. (Table 1)

Technically the command of the Communist troops in Korea was vested in a Combined Headquarters, headed by Premier Kim Il Sung and staffed by North Korean and Chinese officers. Actually enemy operations appear to have been directed by General Peng Teh-huai, from Headquarters, Chinese People's Volunteer Army, in Mukden. Combined Headquarters served as a clearinghouse and message center but the Chinese made certain that their commanders would receive the instructions from Mukden by using direct channels of communication as well. At the front the Chinese had five army group headquarters, each of which controlled two or more armies. (Chart 3)

TABLE 1-EIGHTH ARMY ESTIMATE OF ENEMY FORCES

1 JULY 1951

| Units a | Strength | | Chinese Communist Forces | 248,100 | 12th Army

31st, 34th, 35th Divisions | 16,100 | 15th Army

29th, 44th, 45th Divisions | 14,400 | 20th Army

58th, 59th, 60th Divisions | 16,400 | 26th Army

76th, 77th, 78th Divisions | 19,800 | 27th Army

79th, 80th, 81st Divisions | 26,000 | 38th Army

112th, 113th, 114th Divisions | 13,900 | 39th Army

115th, 116th, 117th Divisions | 24,000 | 40th Army

118th, 119th, 120th Divisions | 18,500 | 42d Army

124th, 125th, 126th Divisions | 29,000 | 47th Army

140th Division | 8,500 | 60th Army

179th, 180th, 181st Divisions | 13,900 | 63d Army

187th, 188th, 189th Divisions | 13,900 | 64th Army

190th, 191st, 192d Divisions | 17,800 | 65th Army

193d, 194th, 195th Divisions | 16,100 | | | Units a | Strength | | Korean People's Army | 211,100 | I Corps

8th, 19th, 47th Divisions | 15,800 | II Corps

2d, 13th, 27th Divisions | 18,800 | III Corps

1st, 15th, 45th Divisions | 30,400 | IV Corps

4th, 5th, 105th Armored Divisions, 26th Brigade | 29,200 | V Corps

6th, 12th, 32d Divisions | 14,300 | VI Corps

9th, 17th Mechanized, 18th, 23d Divisions | 35,500 | VII Corps

3d, 24th, 37th, 46th Divisions, 63d Brigade | 35,500 | | Other forces | 31,800 | |

a Besides these units, Eighth Army Intelligence officers suspected but had not as yet confirmed the presence of six other Chinese armies and two-thirds of a seventh.

Source: Eighth Army G-2 Estimate of Enemy Strength and Locations, 1 Jul 61; Eighth Army G-2 OB Br, CCF Army Histories, 1 Dec 64. Both in ACSI Doc Library DA.

In the Chinese military organization the army was the principal self-sufficient tactical unit. At full strength it had between 27,000 and 30,000 men, roughly comparable to one and a half to two U.S. divisions. Each army contained three divisions and usually included an artillery regiment, security, reconnaissance, engineer, and transport battalions, a signal company, and an army hospital.11 Owing to battle losses during the spring offensives the thirteen plus Chinese armies in Korea were at reduced strength on 1 July. Seven were deployed along or close to the central front and the other six were in reserve.12

CHART 3- CHAIN OF COMMAND OF ENEMY FORCES 1 JULY 1951

Source: (1) Hq FEC MIS, FEC Intel Digest, 16-30 Sep 51, p. 5. (2) Hq USAFFE (Adv), G-2 Intel Digests, 16-31 Jan 53, pp. 32-33; 1-15 Feb 53, pp. 26-28; 16-28 Feb 53, pp. 27-28. (3) Hq FEC MIS, History of the North Korean Army, 31 Jul 52. All in ACSI Doc Lib DA.

The Chinese Communist infantry division was triangular and an average regiment consisted of approximately 3,000 men. Armed with a miscellaneous collection of Russian, Japanese, American, and domestically manufactured copies of foreign weapons, the firepower of a typical regiment might be drawn from the following weapons: 180 pistols, 400 rifles and carbines, 217 submachine guns, 60 light machine guns, 18 heavy machine guns, nine 12.7-mm. antiaircraft machine guns, twenty-seven 60-mm. mortars, twelve 81- or 82-mm. mortars, four 120-mm. mortars, six 57-mm. recoilless rifles, 18 rocket launchers, and four 70-mm. infantry howitzers. The artillery regiment, which was attached to each division, usually consisted of three battalions and contained 36 pieces. Chinese artillery weapons were of Russian, Japanese, and American manufacture and ranged from 75-mm. guns to 155-mm. howitzers.13

The Chinese had shown themselves to be good soldiers. During the first six months of 1951 they had maintained a fluid battle line and had sought to entice the U.N. Command to overextend its forces which they would then try to destroy in detail. Real estate meant little to the Chinese and withdrawal was as important a part of their tactics as was the advance. Herein lay a deep difference between the Chinese and the North Koreans, for the latter fought for the land and consistently showed a strong disinclination to abandon territory.14

Premier Kim Il Sung, the titular commander of General Headquarters, Korean People's Army, at Pyongyang, left direct control over the North Korean forces to his Deputy Commander, Marshal Choe Yong Gun, and Chief of Staff, Nam Il. On the battlefield the highest tactical echelon of command was Front Headquarters under Lt. Gen. Kim Ung, an able and energetic combat leader.15

The North Korean military organization varied in several ways from the Chinese. The corps was the main North Korean tactical unit and customarily approximated two American divisions in strength. But the component divisions of the corps, unlike the Chinese Army in this respect, varied from time to time: the North Koreans were flexible and shifted divisions from corps to corps as the need arose. There were seven North Korean corps in July 1951, and all were in the line- three on the west coast and four on the east. In addition to guarding the flanks against UNC amphibious landings, they anchored the Communist line at the front.

Although the Communist forces could match the U.N. troops in manpower, they were deficient in artillery and armor. According to gun sightings and shell reports, the enemy had about 350 artillery pieces spread along the front in July. The majority were 75-mm. and 76-mm. with some 105-mm., 122-mm., and a few 150-mm. guns and howitzers. Neither the Chinese nor the North Korean infantry units had organic armor. All of the Chinese armored divisions were in China and the lone North Korean tank division was stationed on the west coast north of P'yongyang.16

The enemy offensive capability mounted during July despite the lack of armor and heavy artillery and there were indications that the Communists might be preparing to challenge the almost complete domination of the air enjoyed by the Far East Air Forces (FEAF). Intelligence estimates placed total aircraft based in Manchuria and available to the enemy at 1,050, including 585 fighters, 175 ground aircraft, 100 transports, and 180 training and reconnaissance planes. Some 445 of the fighters were jetpropelled and included the fast Russian MIG-15 which was in some respects superior to the best UNC fighters. FEAF estimated that the Russians were furnishing the aircraft as quickly as the Chinese Communist Air Force trained pilots and maintenance personnel.17

Since the enemy's. passive attitude appeared to be a repetition of earlier instances when the Communists had withdrawn behind a, screening force and prepared for the next offensive, the Eighth Army remained alert and wary. Van Fleet did not appear to be particularly concerned. In a conference with the new commander of the U.S. I Corps, Maj. Gen. John W. (Iron Mike) O'Daniel, on 24 July, Van Fleet said:

". . . if the enemy merely assembles what forces he has, he can only make a limited objective attack, but if he has brought in several more army groups- and frankly we don't know; he could have added up to two more army groups- and has a good amount of supply forward, he may be able to launch an all-out offensive. I don't think he's that strong, but we must be prepared to meet his maximum capability and we must be ready to meet him if the ceasefire negotiations fail."18

The UNC Takes the Initiative

Although Van Fleet felt that the Eighth Army could best meet and punish the enemy at the KANSAS-WYOMING line under the present conditions, he and his staff prepared an offensive plan at Ridgway's request. Submitted in early July, Plan OVERWHELMING outlined a campaign that would take the Eighth Army to the Pyongyang-Wonsan line starting about 1 September, provided that certain conditions were satisfied. If there were a major deterioration of enemy forces or a withdrawal to the north, if the mission of the Eighth Army were changed, or if additional forces were allocated to the Eighth Army, Van Fleet thought that OVERWHELMING might be feasible.19

On to July the Joint Chiefs removed their requirement that Ridgway secure their prior approval of all major ground operations, but the Far East commander took no action on OVERWHELMING.20 The rather formidable set of conditions that Van Fleet had attached to the plan coupled with the initiation of the armistice negotiations argued for a cautious approach to any large-scale offensive at this time. Ridgway therefore decided to observe the course of the peace talks before he acted on OVERWHELMING.21

Van Fleet could still launch limited attacks on his own initiative, but the selection of Kaesong as the truce site eliminated one of the areas that he planned to raid. The possibility of an armistice, moreover, made both sides reluctant to expend men and equipment during most of July. Thus, it was not until the end of the month that Van Fleet issued his first attack order since early June.

The Eighth Army shift from the passive defense was fostered by both external and internal developments. Since the enemy had used the respite on the battlefield to build up his stocks and to bring his combat units up to strength, Van Fleet wanted to probe the Communist defenses, determine the disposition of the enemy troops, and prevent them from employing their mounting offensive capabilities by keeping them off balance.22 In addition, Van Fleet was aware that the combat efficiency of the Eighth Army had slipped during the latter part of July. Patrols were conducted indifferently and failed to bring in prisoners. Gathering intelligence became an increasingly difficult task. Even a stepped-up training program was not enough to restore the ability and will of the Eighth Army to fight. Inactivity and the hope that the armistice talks would prove successful were a tough combination to defeat. As Van Fleet pointed out later: "A sitdown army is subject to collapse at the first sign of an enemy effort .... As Commander of the Eighth Army, I couldn't allow my forces to become soft and dormant."23

In the course of disturbing the enemy's dispositions and of sharpening the fighting edge of the Eighth Army troops, Van Fleet also hoped to improve his own defense positions along the front. There were several areas where the seizure of dominant terrain would remove sags in the line or threats to the UNC lines of communication. One of the sags that Van Fleet wanted to eliminate existed in the rugged Taebaek Mountains in the U.S. X Corps sector.

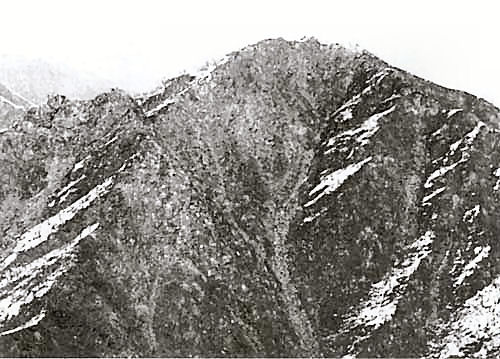

Twenty miles northeast of the Hwach'on Reservoir lay a circular valley known as the Punchbowl and rimmed by hills rising sharply to heights of 1,000 to 2,000 feet above the valley floor. (Map 3) The Soyang River ran south in the valley to the east of the Punchbowl, and on the west the So-ch'on River and one of its tributaries separated the Punchbowl from the next series of ridges. In July the North Koreans held the commanding terrain ringing the Punchbowl on the west, north, and east whence they could observe the UNC defenses and troop movements and could direct artillery fire upon the KANSAS line. Seizure of the enemy positions on the high ground would lessen the threat of attacks developing from these heights aimed at splitting the X and ROK I Corps along the corps boundary which ran to the east of the Punchbowl; it would also allow the Eighth Army to straighten and shorten its lines in the sector and permit Van Fleet to build up larger reserve forces.24 On 21 July Van Fleet directed the X Corps to draw up plans for seizing the west rim of the Punchbowl.

In late July the U.S. 2d Division, commanded by Maj. Gen. Clark L. Ruffner, won a foothold on the western edge of the Punchbowl when the 38th Infantry Regiment captured and set up a patrol base on Hill 1179 called Taeu San.25 Unusually heavy rains that made roads and trails impassable and restricted air and artillery support delayed the launching of further operations in the Punchbowl area until mid-August.26 Diversionary raids in the U.S. I Corps sector in the west on 4 and 8 August had encountered little enemy opposition; most of the difficulties came from the swollen rivers and treacherous roads.27

The PunchbowlOn 18 August the weather had improved sufficiently to permit the summer campaign to get under way. ROK troops from the 11th and Capital Divisions of the ROK I Corps and from the ROK 8th Division of the U.S. X Corps attacked a J-shaped ridge that lay northeast of the Punchbowl. Hill 1031, the highest peak of the ridge, was little more than five miles from the northeast rim of the Punchbowl. The ROK forces under the command of General Paik Sun Yup, ROK I Corps, met with stubborn resistance from elements of the North Korean 45th, 13th, and 2d Divisions who were dug in on the ridge. For eleven days General Paik's forces fought to drive the North Koreans from their strongly fortified positions. While troops from the ROK 8th Division struck north against the hook of the J, the bulk of Paik's men swung in from the east and southeast against the stem. The attacking troops reached their objectives on the ridge lines, but were not reinforced in time to withstand the enemy counterattacks that swiftly followed. The pattern of attack and counterattack without a decision continued until General Van Fleet visited Paik's headquarters and pointed out his tactical mistake. In the next attempt Paik reinforced the attack, seized the hook of the J Ridge on 27 August and cleared the stem two days later.28 Possession of the J Ridge provided protection for the Eighth Army supply route along the Soyang Valley and permitted the ROK I Corps to observe and fire upon enemy positions and troop movements north of the Punchbowl.

Bloody RidgeOn the same day- 18 August- that the attack against the J Ridge had begun, the 36th Regiment of the ROK 5th Division had attempted to seize another ridge west of the Punchbowl. Van Fleet had directed Maj. Gen. Clovis E. Byers, the new commander of the U.S. X Corps, to eliminate important enemy observation posts that directed heavy and accurate artillery fire upon Line KANSAS position from the ridge, some two miles west and slightly south of Hll 1179. Since Van Fleet believed that the South Korean troops lacked self-confidence and needed experience to develop faith in their own abilities, he instructed Byers to use ROK units in the assault.29 Byers in turn attached the 36th Regiment to the U.S. 2d Division.

The objective was an east-west ridge with three peaks, the highest at the western end rising to 983 meters. The ridge formed the crossbar of an H-shaped hill mass that overlooked the forward positions of the 2d Division some two miles south of Hill 983. After five days of repeated frontal assaults the ROK 36th Regiment took the ridge, later called Bloody Ridge, but then had to withdraw under heavy North Korean pressure.30 General Ruffner, the 2d Division commander, had to commit elements of the U.S. 9th Regiment to support the South Koreans, but still the enemy refused to give ground.31 The North Koreans were protected by thick mine fields and strongly built bunkers that resisted destruction by anything less than accurate direct fire. With ample supplies of automatic weapons and hand grenades, they waited in their bunkers until the UNC artillery and air support ceased. Then, as the Eighth Army soldiers labored up the last few yards of the steep slopes, the Communist troops would move out into their firing positions and send a hail of bullets and grenades at the attackers.

The steadily mounting casualty lists led to a decline in morale among the men of the ROK 36th Regiment. On 27 August some units of the regiment broke and ran, spreading panic among the elements of the U.S. 9th Regiment as well.32 The deterioration of the situation on Bloody Ridge led General Byers on 28 August to alter his approach and he decided upon a limited advance along the whole corps front, starting on 31 August. By applying pressure over a broad front, Byers hoped to force the enemy to disperse his firepower and to halt the flow of enemy reinforcements to Bloody Ridge. Thus, Byers rearranged divisional objectives along the corps front. The seizure of the northwest rim of the Punchbowl was assigned to the ROK 5th Division and the northeast rim was given to the U.S. 1st Marine Division. While the 2d Division renewed its efforts to take Bloody Ridge, the ROK 7th Division would attack and capture terrain west of the ridge.

Although the 1st Marine Division and its attached Korean Marine troops met little opposition on 31 August as they began their advance, the enemy forces stiffened the following day. Yet despite the increasing resistance the marines were able to push forward and take several hills on the northern rim of the Punchbowl. By a stroke of good fortune, the N.K. III Corps was in the process of moving from the ROK I Corps front and of taking over the defense of this sector from the N.K. II Corps. As the N.K. 2d Division began the relief of the N.K. 1st Division, the marines hit the latter's positions. By the time the relief was completed, in the opening days of September, the marines had won control of the northern lip of the Punchbowl.33 The 9th Infantry attacks on Bloody Ridge at the end of August and the opening days of September, on the other hand, failed to dislodge the enemy, whereupon Byers and Brig. Gen. Thomas E. de Shazo, who had temporarily taken command of the 2d Division, laid out a double envelopment of Bloody Ridge using elements of the U.S. 23d and 38th Regiments while the 9th continued its assault on the ridge itself.34

On 4 and 5 September the anticlimax came. With surprising ease the 2d Division forces advanced and took over Bloody Ridge. The North Koreans, weakened by heavy losses, had finally evacuated their positions and left substantial stores of supplies and over 500 dead on the heights. After almost three weeks of fighting and over 2,800 U.N. and ROK casualties, the Eighth Army had won its objective. According to 2d Division estimates, the defense of Bloody Ridge had cost the enemy over 15,000 casualties.35

The advance by the X Corps in August demonstrated once again the reluctance of the North Koreans to part with any of their territory. Taking excellent advantage of the terrain and constructing well-placed defenses, they had fought bitterly to hold on to their observation posts on Bloody Ridge. Only when the attack had been broadened to apply pressure at several points along the corps front, and the 2d Division had committed elements of all three of the division's regiments, and only after enemy forces suffered severe casualties, did the North Koreans concede and evacuate the ridge.

Heartbreak Ridge

In any event Bloody Ridge had its after effects. During the battle Van Fleet had submitted an outline plan, called TALONS, to Ridgway envisioning an advance ranging from one to almost fifteen miles to remove the sag in the Eighth Army's eastern front. Ridgway had turned down more ambitious plans for an amphibious landing near Wonsan and for a deep advance into North Korea, but he had no objection to a modest ground offensive.36 Preparations for TALONS continued until 5 September, when Van Fleet evidently took a close look at the final casualty totals of the Bloody Ridge fight. Since TALONS would be on a much larger scale, Van Fleet decided that the operation was not worth the probable cost in lives and materiel. Instead he informed Ridgway that he favored sustaining his "tidying up" on the Eighth Army right flank during the remainder of September, using "elbowing" tactics without any definite objective line assigned. Around 1 October he would stop his offensive operations in the east, then launch an attack in the west by the U.S. I Corps about the middle of the month, provided the armistice negotiations permitted. If this I Corps maneuver were successful, Van Fleet would follow up with an amphibious operation on the east coast near Tongch'on. This would link up with a land advance northeast from Kumhwa.

Heartbreak RidgeThe quick change in plans by the Eighth Army commander caught Ridgway by surprise, but he interposed no objection to the continuance of the limited objective attacks on an opportunistic basis. The proposed amphibious assault, however, Ridgway would only approve for planning purposes.37

Acting swiftly, Van Fleet issued a general directive to his corps commanders on 8 September emphasizing limited objective attacks, reconnaissance, and patrolling.38 He followed up the directive the same day with instructions to the X Corps to take the ridge just north of Bloody Ridge and another north of the Punchbowl. Since the North Koreans opposite the X Corps had just sustained a defeat on Bloody Ridge, Van Fleet thought that immediate thrusts would keep the enemy off balance and would gain the new ridge lines before the Communists had a chance to recover.39

The X Corps assigned the task of taking the peaks north of Bloody Ridge to the U.S. 2d Division. The objective was the southern tip of a long, narrow ridge running north and south between the Mundung-ni Valley on the west and the Sat'ae-ri Valley on the east; spur ridges arching east and west from the main ridge caused one observer to describe the objective as the "spinal column of a fish, with hundreds of vertebrae."40 Possession of the central ridge would prevent the enemy from using the adjacent valleys to attack the X Corps defense lines west of the Punchbowl.

Heartbreak Ridge, as the objective was later named by news correspondents covering the action, had three main peaks. At the southern terminus was Hill 894 which commanded the approach from Bloody Ridge, three miles to the south; Hill 931, the highest peak in the ridge, lay 1,300 yards to the north; and 2,100 yards north of Hill 931 rose the needlelike projection of Hill 851.

After withdrawing from Bloody Ridge, the North Koreans had fallen back to prepared bunkers, trenches, and gun positions covering the approach ridges to Heartbreak that were just as strongly fortified and as well camouflaged as those previously encountered by the 2d Division. The respite between the end of the Bloody Ridge battle on 5 September and the assault on Heartbreak Ridge eight days later permitted the North Koreans to strengthen their defenses even further and to reinforce the units guarding the ridge and its approaches. In the Mundung-ni Valley the North Korean 12th Division of the III Corps controlled the hills on the western side of the Suip-ch'on River and the 6th Division of the same corps was responsible for the Heartbreak Ridge and Sat'ae-ri Valley sectors. Aerial photos had disclosed that the enemy had been very active in the Heartbreak Ridge area, grouping artillery and mortar units in the valleys flanking the ridge. But the heavy woods and undergrowth had veiled the elaborate enemy fortifications from the camera's eye and concealed the fact that the 2d Division was again faced with the task of breaching the enemy's main line of resistance.

Within the 2d Division there was considerable difference of opinion on the extent of the expected enemy reaction to an attack on Heartbreak Ridge. Col. Edwin A. Walker, the artillery commander, felt that the North Koreans would "fight like hell" for it, while some members of the staff contemplated that the enemy response would be less vigorous. General de Shazo, the acting division commander, evidently was among the latter group. He decided to use one regiment- the 23d- rather than two in the assault force. Approaching from the east across the Sat'ae-ri Valley, the 23d, under Col. James Y. Adams, would cut Heartbreak between Hills 931 and 851. One battalion would then turn north to seize Hill 851 while a second would move south to capture Hills 931 and 894. As soon as Hill 894 came under the control of the 23d, the 9th Infantry, under Col. John M. Lynch, would advance and take Hill 728, 2,000 yards to the west and slightly south of Hill 894.

On 13 September the elements of the 2d Division were in position and ready to attack. The French Battalion, under Lt. Col. Ralph Monclar, had taken over the positions of the 38th Infantry Regiment on Hill 868, a little over two miles east of Hill 931, and the 38th had become the division reserve with responsibility for surveillance of the KANSAS line. The 9th Regiment was poised to advance on Hill 728 when the 23d Regiment gained Hill 894. Direct support for the 23d Regiment would come from the 37th Field Artillery Battalion, under Lt. Col. Linton S. Boatright, and its 105-mm. howitzers, while the 503d Field Artillery Battalion (155-mm. howitzer) , 96th Field Artillery Battalion (155-mm. howitzer) , 38th Field Artillery Battalion (105-mm. howitzer), and Battery C of the 780th Field Artillery Battalion (8-inch howitzer) provided general support. The 37th and 38th Field Artillery Battalions were located about three miles southeast of Heartbreak Ridge. The 96th and 503rd were approximately seven miles south and nine miles southeast of the objective respectively, while the battery from the 780th was near Yach'on-ni, about eleven miles south of Heartbreak.

At 0530 the artillery preparation began and for thirty minutes the guns pounded enemy positions on or near Heartbreak Ridge. Then Colonel Adams, a 6-foot 6-inch West Pointer, gave the signal to start the 23d's attack. The 3d Battalion, under Lt. Col. Virgil E. Craven, led the way in a column of companies, followed by the 2d Battalion, commanded by Lt. Col. Henry F. Daniels. As the assault troops moved north from Hill 702 up the Sat'ae-ri Valley to reach the east-west spur ridge that would serve as the approach to Heartbreak, the North Koreans spotted them. Heavy artillery and mortar fire from Heartbreak Ridge positions and from the heights around Sat'ae-ri town began to pour in on the men of the 23d Regiment. Despite the growing number of casualties, Craven's forces pressed on, closely followed by Daniels' men. As the 3d Battalion arrived at the east-west spur and headed up the hill to split the Heartbreak Ridge line, it ran into a hornet's nest. The 1st Regiment of the N.K. 6th Division manned a series of concealed, mutually supporting bunkers that covered the approach ridge with machine guns and small arms. Added to the artillery and mortar fire that the enemy observers were directing upon the two attack battalions, the automatic weapons and rifle fire forced the assault force to halt and dig in on the toe of the spur. The prospects for a swift penetration of the enemy lines vanished as night fell; the 23d had come up against the main defenses of the North Koreans and another Bloody Ridge experience loomed ahead.

When reports of the 23d's situation reached General de Shazo, he realized that he had underestimated the enemy's defensive capacity. Since the 9th Regiment, under Colonel Lynch, was already in position for its contemplated attack on Hill 728, de Shazo directed Lynch on 14 September to use his regiment against Hill 894 instead. A successful seizure of Hill 894 could relieve some of the pressure on the 23d Regiment.

The 2d Battalion of the 9th Regiment advanced from Yao'dong up the southwest shoulder of Hill 894 on 14 September, supported by tanks of Company B, 72d Tank Battalion, the heavy mortar company, and a battalion of 155-mm. howitzers. By nightfall the 2d Battalion had climbed to within 650 yards of the crest of Hill 894 against light enemy resistance. The attack continued on 15 September and by afternoon, the height was swept clear of the enemy. Up to this point the 2d Battalion had had only eleven casualties, but the next two days cost the battalion over two hundred more as the North Koreans counterattacked fiercely and repeatedly in a vain effort to drive it off the crest.

Possession of Hill 894 by the 9th Regiment failed, however, to relieve the pressure on the 23d as it sought again to cut the ridge line between Hills 931 and 851. The enemy's firepower kept the assault forces pinned down on the lower slopes. On 16 September Colonel Adams ordered his 2d and 3d Battalions to shift from the column formation they had been using to attack abreast. Thus, while the 3d Battalion renewed its drive due west, the 2d Battalion swung to the southwest and approached Hill 931 along another spur. In the meantime, C Company of the 1st Battalion passed through the positions of the 9th Regiment on Hill 894 and tried to take Hill 931 from the south. The three-point attack made little headway against the heavy curtain of fire laid down by the enemy.

Secure in their strongly fortified bunkers, the North Korean defenders waited until the artillery and air support given to the 2d Division assault forces was lifted and then returned to their firing positions. As the 23d Regiment's soldiers climbed the last few yards toward the crest, the North Koreans opened up with their automatic weapons, rifles, and grenades. Since the enemy controlled the Mundung-ni Valley which offered defiladed and less steep access routes to Heartbreak Ridge, the problem of reinforcements and resupply was not difficult to resolve. In fact, General Hong Nim, commander of the N.K. 6th Division, managed to send the fresh 13th Regiment in to replace the 1st Regiment on 16 September without any trouble.

For the U.S. 2d Division, the outlook was rather grim. The narrow Pia-ri Valley, southwest of Heartbreak, was jammed with vehicles and exposed to enemy artillery and mortar fire. Korean civilian porters frequently abandoned their loads along the trails and bolted for cover when the enemy got too close. To keep the frontline units supplied with food, water, ammunition, and equipment and to evacuate the casualties often required that American infantrymen double as carriers and litter bearers. The rugged terrain and the close enemy surveillance of the approaches to Heartbreak Ridge made their jobs very hazardous and time consuming, for it could take up to ten hours to bring down a litter case from the forward positions held by the 23d Regiment.

The stalemate on the ridge led Colonel Lynch on 19 September to suggest a broadening of the attack to dissipate the enemy's concentrated resistance. He urged General de Shazo to let 1st Battalion of his 9th Regiment move across the Mundung-ni Valley and seize Hills 867 and 1024 located about three and four miles, respectively, southwest of Hill 894. If the enemy assumed that this attack marked the beginning of an envelopment of Heartbreak Ridge from the west, he might well divert men and guns to block the challenge, Lynch reasoned. But de Shazo rejected the proposal since General Byers, the X Corps commander, had earlier directed that Hill 931 be given first priority.

When Maj. Gen. Robert N. Young, the new 2d Division commander, arrived the following day, he decided that Lynch's plan was sound. He ordered Lynch to take Hills 867 and 1024 and the 9th Infantry commander scheduled the attack on Hill 1024 for 23 September; Hill 867 would be seized after Hill 1024 fell. In the meantime, Van Fleet told Byers that it would be desirable for the X Corps to advance its western flank to bring the front line into phase with the U.S. IX Corps'. Thus, Byers, on 22 September, directed the ROK 7th Division to capture Hill 1142, located about 2,000 yards northwest of Hill 1024. The double-barreled attack upon Hills 1024 and 1142 might well cause the North Koreans to take the threat seriously and lessen their capacity to resist on Heartbreak Ridge.

The attacks by the 23d Infantry against Heartbreak Ridge had continued on 21 and 22 September with little success. The 1st Battalion, under Maj. George H. Williams, Jr., had tried again to take Hill 931 from the south, while Daniels' 2d Battalion came in from the north. Elements of the 1st Battalion briefly won their way to the crest on 23 September, but could not withstand the enemy's counterattack. An early morning assault from the east by a company from the 3d Regiment, N.K. 12th Division, produced a fierce fight that decimated the 1st Battalion. When his ammunition ran out, Williams had to pull back his men from Hill 931.41

Across the Mundung-ni Valley the diversionary attacks against Hills 1024 and 1142 by the 9th Regiment and the ROK 7th Division made good progress. On 25 September the 1st Battalion, 9th Infantry, cleared the crest of Hill 1024 and the ROK 7th Division won Hill 1142 the following day. Recognizing the threat to neighboring Hill 867, a key terrain feature dominating the valley to the north, the North Koreans quickly shifted the 3d Regiment, N.K. 6th Division, from Heatbreak Ridge to defend the hill.

The North Korean deployment, however, did not help the embattled 23d Regiment to capture Hill 931. Although the French Battalion replaced the 2d Battalion and tried to advance south along the ridge line while the 1st Battalion sought to press north toward the crest of 931, the N.K. 15th Regiment fought them off on 26 September. The 23d's regimental tanks were able to move far enough north in the Sat'ae-ri Valley to send direct fire against some of the enemy's bunkers covering the eastern approaches to Heartbreak, but could not destroy the heavy mortars and machine guns that halted the 2d Division attack.

After almost two weeks of futile pounding at the enemy's defenses on Heartbreak, Colonel Adams told General Young on 26 September that it was "suicide" to continue adhering to the original plan. His own 23d Regiment had already taken over 950 casualties and the division total for the period was over 1,670. As Colonel Lynch had the week before, Adams favored broadening the attack and dispersing the enemy's capacity to resist on Heartbreak. He felt that if the North Korean forces in the vicinity of Heartbreak were engaged and unable to spare reinforcements or replacements for the N.K. 15th Regiment, the 23d could wear the enemy regiment down and win the ridge.

By 27 September Young and the corps commander, General Byers, had come to agree with Adams and further assaults by the 23d on Heartbreak were called off. Analyzing the intial attempts of 2d Division to take Heartbreak, Young later characterized them as a "fiasco" because of the piecemeal commitment of units and the failure to organize fire support teams. The enemy mortars were especially effective, he pointed out, causing about 85 percent of the division's casualties up to this point.

In the new plan that the division G-3, Maj. Thomas W. Mellon, prepared in late September, the earlier mistakes were to be avoided. All three regiments of the division would launch concentrated and co-ordinated attacks, supported by all the division's artillery, by a fullscale armored drive by the 72d Tank Battalion up the Mundung-ni Valley, and by tank-infantry task force action in the Sat'ae-ri Valley. When the division issued the operation order on 2 October under the code name TOUCHDOWN, General Young assigned the following objectives to his regiments. The 9th Infantry would advance on the western side of the Mundung-ni Valley and seize Hills 867, 1005, 980, and 1040. To the 23d went the task of securing Hill 931 and the ridge line running west of that peak. In addition, the 23d would be ready to attack Hill 728 or to help the 38th capture it, as the case might be, and to take Hill 520, west of Hill 851. The 38th would secure Hill 485 and then provide infantry support to the 72d Tank Battalion. Target date for TOUCHDOWN was 5 October.

The preparations for TOUCHDOWN required a period of tremendous activity on the part of the 2d Engineer Combat Battalion and its commander, Lt. Col. Robert W. Love. The road along the Mundung-ni Valley was a rough track unsuitable for the medium Sherman tanks of the 72d Tank Battalion and to get it quickly into condition to carry the M4's was a herculean task.42 But Love and his men were willing to try if they had adequate fire cover while they worked.

Craters dotted the track and the North Koreans had planted mines along the way. At one point they had heaped large rocks six feet high and sprinkled the pile with hand grenades, each with its pin pulled. The 2d Engineers put 110 pounds of explosives around this roadblock and detonated the grenades when the explosives went off. Rock from neighboring cliff walls was blasted to provide fill for the craters. Working with shovels because their bulldozers were undergoing repair and would, in any case, have drawn artillery fire from the enemy on the heights further up the valley, the engineers fashioned a usable road. To take care of the mines along the trail, they placed chain blocks of tetranol at 50-foot intervals on the sides of the track and then set them off. The explosions detonated the mines nearby. When the craters and mines were too dense, the engineers shifted the road to the stream bed, which had not been mined, and cleared the boulders blocking the way. Bit by bit they advanced northward up the valley.

While the engineers prepared the path for the tank attack, the 2d Division regiments received replacements to bring their battalions up to full strength and built up their supplies of food, equipment, and ammunition for the upcoming operation. The 23d Regiment pulled each of its battalions out of the line for forty-eight hours so that the replacements could be integrated while the unit was in reserve rather than on the line. The division established supply points forward of Line KANSAS to insure that the operation did not fail because of ammunition shortages.

General Young also wanted to be certain that his battalion commanders would make full use of all the firepower at their disposal. Each battalion had to submit fire plans showing how it intended to employ its tanks, automatic weapons, small arms, and mortars in TOUCHDOWN. Sand-table models of the Heartbreak Ridge sector were used extensively in positioning the division's weapons in the best possible locations.

Early in October, the three regiments moved into their attack positions. The 9th was on the left flank, ready to advance upon Hill 867 while the 38th, under Col. Frank T. Mildren, was going up the Mundung-ni Valley. The 38th would stop near Saegonbae, southwest of Hill 894. The 3d Battalion of the 38th was to be the division reserve and could be used only with the permission of General Young. The attached Netherlands Battalion, however, provided the 38th with three full battalions. On Heartbreak Ridge the 23d Infantry maintained two of its four battalions on the lines between Hills 894, 931, and 851.

To protect the division's right flank in the Sat'aeri Valley area and to distract the enemy, a task force under Maj. Kenneth R. Sturman of the 23d Infantry Regiment was organized on 3 October. Composed of the 23d Tank Company, the 2d Reconnaissance Company, a French pioneer platoon, and an infantry company from the special divisional security forces, Task Force Sturman, as it was called, had the secondary mission of destroying enemy bunkers on the east side of Heartbreak Ridge and of acting as a decoy to draw enemy fire away from the 23d Infantry foot soldiers on the ridge.

On 4 October forty-nine fighter-bombers worked over the divisional sector and the Sturman force raided the Sat'ae-ri Valley. The other units of the 2d underwent final rehearsals for the attack scheduled for 2100 hours the next night. Fire support teams usually consisting of a combination of mortars, machine guns, rifles, and automatic weapons that could be called upon by the attacking infantry whenever the need arose were set up and given dry runs. The additional firepower would be extremely valuable against enemy bunkers and strongpoints.

In the late afternoon of 5 October, the artillery preparation opened up as the division's artillery battalions began to pummel the defending enemy units facing the 9th and 38th Regiments in the Mundung-ni Valley area. Deployed from west to east the 3d Regiment, N.K. 12th Division, occupied Hill 867; the 1st Regiment, N.K. 6th Division, was spread from Hill 636 northwest to Hill 974; and the 15th Regiment, N.K. 6th Division, was dug in on Hill 931. As a result of the constant pressure exerted by the 2d Division on these units during September and early October, none of them had a strength that reached a thousand men. The N.K. 12th and 6th Divisions were both far understrength by the eve of TOUCHDOWN.

Air strikes by Marine Corsairs sent napalm, rockets, and machine gun bullets into the North Korean lines before the attack jumped off that evening. On the west the 3d Battalion, 9th Infantry, pressed on toward Hill 867 and by 7 October had won the crest, meeting only light resistance. The battalion then swung northwest toward Hill 960 while the 1st Battalion mounted an attack north against Hill 666. Both hills fell on 8 October. Then the 9th pushed on to Hill 1005 northwest of Hill 666 and after a bayonet assault took possession on to October. On the following day the ROK 8th Division gained Hill 1050 and the Kim Il Sung range to the west of the 9th Regiment.43

The 38th Regiment, in the meantime, had also made excellent progress. Colonel Mildren's troops had had a windfall on 4 October when they discovered that the enemy had abandoned Hill 485, a mile south of Hill 728. By noon on 6 October the 1st Battalion had advanced from Hill 485 and seized Hill 728 against only light enemy opposition. The 2d Battalion deployed up the Mundung-ni Valley and attacked Hill 636 which fell on 7 October. Possession of these two hills furnished cover for Colonel Love's engineers, who could now complete the tank trail for the 72d Tank Battalion's advance. The 72d, commanded by Lt. Col. John O. Woods, was attached to the 38th on 7 October and the regiment was given three new objectives: Hill 605, 2,000 yards north of Hill 636; the Hill 905-Hill 974 ridge which extended northwest from Hill 636 toward Hill 1220 on the Kim Il Sung range; and Hill 841, a thousand yards north of Hill 974.

Up on Heartbreak Ridge the 23d Regiment was also able to report encouraging news. Colonel Adams' battle plan had directed Major Williams' 1st Battalion to exert diversionary pressure north against Hill 851, while the French Battalion feinted south toward Hill 931. Daniels' 2d Battalion would hit Hill 931 from the south with Craven's 3d Battalion as reserve behind Daniels. Under cover of night and the distractions provided for the enemy by the rest of the division, Daniels' troops moved out. Enemy fire came in quickly upon the battalion, but the North Koreans could not concentrate all their attention upon this assault. With the 3d Battalion in support, Daniels' force slowly approached Hill 931. To preserve the element of surprise, there had been no artillery preparation. The 37th Field Artillery Battalion opened up on all known enemy mortar positions as the attack got under way. The effectiveness of the countermortar fire helped the 23d infantrymen as they closed with the North Koreans after only light losses.

Flame throwers, grenades, and small arms rooted the enemy from the formidable bunkers that had blocked the 23d's advance for so many weeks. By 0300 the 2d and 3d Battalions had won the southern half of Hill 931. The expected enemy counterattack came and was repulsed. With the coming of daylight, the advance was renewed. The French Battalion moved in from the north and the 2d and 3d Battalions pressed on to meet it; before noon Hill 931 finally belonged to the 23d Infantry.

Craven's 3d Battalion then pushed on to join the 1st Battalion in its assault against the last objective on Heartbreak Ridge - Hill 851. In the Sat'ae-ri Valley, Sturman's tanks sustained their daylight raids and continued to blast away at the bunkers on the eastern slopes of Hill 851. On the west, in the Mundung-ni Valley, Woods's 72d Tank Battalion awaited the go-ahead signal from Love's engineers.

On 10 October the engineers finished their, task and the 72d's Shermans, accompanied by Company L, 38th Infantry, and an engineer platoon, began to rumble north up the valley. By a fortunate coincidence the enemy was caught in the middle of relieving the rapidly disintegrating elements of the N.K. V Corps in the Heartbreak Ridge-Mu-dung-ni sector. Advance elements of the 204th Division, CCF 68th Army, were in the process of taking over positions already vacated by the North Koreans. The tank thrust coupled with the general forward movement of the rest of the 2d Division found the Chinese still in the open en route to their new positions. Woods's tankers raced to the town of Mundung-ni and beyond, taking losses on the way, but inflicting heavy losses upon the Chinese troops and cutting off the supply and replacement routes up the western slopes of Heartbreak Ridge. At intervals of about 100 yards the tanks, operating without infantry in the northern reaches of the valley, were able to cover each other and fire at targets of opportunity. They disrupted the enemy relief completely and made the task of the infantry much lighter in the days that followed. It was apparent that the enemy had thought that tanks could not be used in Mundung-ni Valley and the feat of Love's engineers in opening a road had taken him by surprise.

The battle, however, was not quite over. The 3d Battalion, 38th Infantry, took advantage of the tank advance to seize Hill 605, but the 2d Battalion's attempts to capture Hill 905 were blunted on 10 October. The next day the 2d Battalion overcame enemy opposition and the 1st Battalion took Hill 900. On 12 October the 1st Battalion pushed on toward the Kim Il Sung range and captured Hill 974. The final objective of the 38th- Hill 1220- fell on 15 October.

On Heartbreak Ridge the 23d Regiment, N.K. 13th Division, defended Hill 851, backed by its sister regiments, the 21st and 19th. The 21st was to the immediate rear and the 19th defended the Sat'aeri Valley. On 10 October, Colonel Daniels' 2d Battalion had swung down from Heartbreak Ridge and taken possession of Hill 520, a little over a mile south of the town of Mundung-ni. Hill 520 was the end of an east-west ridge spur leading to Hill 851. During the next two days, the 1st and French Battalions inched north toward the objective, bunker by bunker, taking few prisoners in the bitter fighting. The North Koreans and their Chinese allies who had succeeded in joining them on Hill 951 had to be killed or wounded before they would cease resistance. Colonel Craven's 3d Battalion shifted to the spur between Hills 520 and 851 to apply pressure from the west. Finally at daybreak on 13 October, Monclar's French troops stormed the peak and after thirty days of hard combat, Heartbreak Ridge was in the possession of the 23d Infantry to stay.

The costs of the long battle were high for both sides. The 2d Division had suffered over 3,800 casualties during the 13 September-15 October period, with the 23d Regiment and its attached French Battalion incurring almost half of this total.44 On the enemy side the North Korean 6th, 12th, and 13th Divisions and the CCF 204th Division all suffered heavily. Estimates by the 2d Division of the enemy's losses totaled close to 25,000 men.45 Approximately half of these casualties had come during the TOUCHDOWN operation.

The increase in casualties had been accompanied by a similar rise in ammunition expenditures. Besides the millions of rounds of small arms ammunition that were used, the 2d Division infantrymen received the following artillery support: 76-mm. gun- 62,000 rounds; 105mm. howitzer- 401,000 rounds; 155-mm. howitzer - 84,000 rounds; and 8-inch howitzer- 13,000 rounds. The division's mortar crews sent over 19,000 rounds of 60-mm., 81-mm., and 4.2-inch mortar fire and the 57-mm. and 75-mm. recoilless rifle teams directed nearly 18,000 rounds at the enemy.46 Although there were shortages in some types of ammunition at the theater level, Van Fleet had given the 2d Division commander permission to fire "all the ammunition thought necessary to take the positions." When 81mm. mortar shells became short in supply, the 4.2-inch were used more frequently. To keep the 4.2-inch mortars in operation, an airlift from Pusan brought 2,500 rounds a day for four days, while a special rail shipment with 25,000 rounds was rushed to the front.

To supplement the artillery support given the division, the Fifth Air Force flew 842 sorties over the Heartbreak Ridge area and loosed 250 tons of bombs on the enemy.47 Against the deep bunkers of the North Koreans, anything less than a direct hit was ineffective, but Colonel Adams felt that the air strikes were good for morale. He also gave the fighter-bombers credit for neutralizing artillery and mortar fire during a battalion relief on 27 September so that the 23d could make the shift without casualties.48

There were many points of similarity between the Heartbreak Ridge struggle and its immediate predecessor - Bloody Ridge. In both cases the North Koreans had organized strong defensive positions in depth and had had the advantage of defiladed routes to bring in logistical support and reinforcements. The UNC forces had to advance over exposed routes which the enemy artillery and mortar fire covered very effectively. The 2d Division advance was extremely hazardous and slow as long as the North Koreans were allowed to concentrate their fire on relatively few targets.

In both attacks, enemy capabilities and will to resist had been underestimated. Each had been planned as a small-scale advance to straighten out a front-line sag and each had suffered from a lack of adequate reserves to reinforce and consolidate the objectives after they were won. After the North Koreans counterattacked the Eighth Army forces, the latter had been compelled to withdraw. At Heartbreak the corps commander, General Byers, had not permitted the 2d Division to use the 38th Regiment until Operation TOUCHDOWN, although it was apparent long before then that the 23d would not be able to take the ridge as long as the enemy could focus his attention upon Colonel Adams' units. The 38th had remained the divisional reserve until October despite the need for its services.

At the command level the 2d Division had had a change in leadership during the two operations. General de Shazo had taken over the division while the Bloody Ridge fight was still in progress and he in turn had been succeeded by Young after the Heartbreak contest was well under way. Each had brought the operation he had inherited to a successful conclusion, but only after a considerable expansion of the original battle plan.

Final attainment of the objective had occurred when the pressure upon the enemy had been applied at several points rather than one. Then, unable to funnel in replacements to all the threatened positions or to concentrate his artillery and mortar fire within a small area, the enemy had reluctantly withdrawn to his next defense line. Frequently, despite the artillery, tank, and air support given to the U.N. foot soldiers, the North Koreans would leave only after they had been flushed from their bunkers by infantry weapons. The North Koreans at Bloody and Heartbreak Ridges had fought with determination and courage throughout the battles until attrition and superior strength had forced them to yield their real estate.

With the successful conclusion of the TOUCHDOWN operation X Corps had removed the sag in the Punchbowl area and in the lines held by the U.S. 2d and ROK 8th Divisions to the west of the Punchbowl. Advances of over five miles along this front had shortened the X Corps' lines and had brought them into phase with those of the U.S. IX Corps to the west.

Advance in the West

Shortly after the Heartbreak Ridge operation got under way in September, General Van Fleet and his staff drew up plans for an ambitious advance in the U.S. I and IX Corps sectors. Since the important Ch'orwon-Kumhwa railroad was exposed to enemy artillery fire and attack, Plan CUDGEL, envisioned a 15 kilometer drive forward from WYOMING to protect the railroad line and to force the enemy to give up his forward positions. Besides improving communications in central Korea, Van Fleet intended to use the railroad to support a followup operation in October which he had named WRANGLER.49 The latter was equally ambitious, for it aimed at cutting off the North Korean forces opposing the ROK I and U.S. X Corps on the right flank of the Eighth Army by an amphibious operation on the east coast. If this operation were successful, the forward line of the Eighth Army would run between P'yonggang and Kojo.50 For the landing force, Van Fleet proposed to use U.S. Marine forces with a ROK division following them into the Kojo beach area. The Eighth Army commander frankly recognized that this operation would be a calculated risk and might lead to a dangerous enemy counterthrust on the west flank as the amphibious forces tried to link up with the U.S. IX Corps along the KumsongKojo road.51

Although Van Fleet asked Ridgway for a quick decision, on CUDGEL and WRANGLER, he discarded them himself within a few days just as he had canceled out TALONS earlier in the month. Consideration of the probable costs of CUDGEL led him to accept instead a substitute plan submitted by General O'Daniel, the I Corps commander, at the end of September. O'Daniel outlined a modest 10-kilometer advance by the I Corps to a new defense line called JAMESTOWN, which would allow that corps to strengthen its supply lines by reducing the truck hauls during the winter months. JAMESTOWN began on the west bank of the Imjin River a little over 9 miles northeast of Munsan-ni, then arched gently northeast to the town of Samich'on on the Samich'on River. For that next to miles JAMESTOWN ran northeast, rejoining the Imjin River near the town of Kyeho-dong, then hugged the high ground south of the Yokkokch'on for about 12 miles until it reached the area of Chut'oso, six miles northwest of Ch'orwon. From Chut'oso, JAMESTOWN ran east by north for about 10 miles, ending approximately 5 miles northeast of Ch'orwon at the village of Chungasan. Seizure of the key terrain features along this line would screen the Yonch'on-Ch'orwon Valley lines of communication from enemy observation and artillery fire, permit development of the SeoulCh'orwon-Kumhwa railroad line, and allow the main line of resistance to be advanced. (Map II) In addition, the I Corps offensive would keep the enemy off balance and prevent the Eighth Army troops from getting stale.52

October was a good month for operations in the west central part of Korea, since the weather was usually dry. This permitted full air support and eliminated the problems of flash floods and heavy mud. Terrain in the I Corps sector varied from low lands in the west to small, steep hills in the center and low rolling hills on the eastern fringes of the corps boundary.

To carry out Operation COMMANDO, as the I Corps advance was called, General O'Daniel planned to use four divisions from his own corps and one from the neighboring U.S. IX Corps to prevent the development of a sag along the corps boundaries. On the corps' western flank the ROK 1st Division, commanded by Brig. Gen. Bak Lim Hang, would leave Line WYOMING, cross the Imjin River, and move toward Kaesong. The British Commonwealth Division, under General A. J. H. Cassels, was on the eastern flank of the ROK 1st and would take the high ground between Samich'on and Kyeho-dong. Still farther east, the 1st Cavalry Division, under Maj. Gen. Thomas L. Harrold, would move to the northwest on an 8-mile front between Kyehodong and Kamgol.53 On the corps' right flank, Maj. Gen. Robert H. Soule's 3d Division would advance and capture Hill 281, six miles northwest of Ch'orwon, and Hills 373 and 324, seven miles west by north of the city. The 3d Division would also link up at Chungasan with the IX Corps' 25th Division, now commanded by Maj. Gen. Ira P. Swift, as the 25th advanced to take over defensible terrain north of the confluence of the Hant'an and Namdae Rivers northeast of Ch'orwon.54

Elements, of four Chinese armies - the 65th, 64th, 47th, and 42d -would have to be pushed back before JAMESTOWN could be reached, but as Van Fleet remarked to the press on 30 September, the basic mission of the Eighth Army was to seek out and destroy the enemy.55

When COMMANDO began on 3 October, the enemy centered his resistance in the 1st Cavalry Division zone. The ROK 1st, 1st Commonwealth, 3d, and 25th Divisions met only light to moderate opposition as they advanced to take their assigned objectives along the JAMESTOWN line, but the 1st Cavalry Division units had to battle for every foot of ground. Elements of the 139th and 141st Divisions of the CFF 47th Army manned the enemy's main line of resistance facing the 1st Cavalry Division and they had constructed defenses similar to those encountered on Heartbreak Ridgestrong bunkers supporting each other with automatic weapons fire, and with heavy concentrations of artillery and mortars interdicting the approach routes to the hills and ridges. Barbed wire aprons and mines guarded the trenches and bunkers and the Chinese were well stocked in ammunition and supplies.56

General Harrold had the 70th Tank Battalion under Maj. Carroll McFalls, Jr., and the 16th Reconnaissance Company operate as a task force on his left flank. The mission of the Task Force Mac, as it was called, was to advance along the east bank of the Imjin River toward Kyeho-dong, tieing in with the 1st Commonwealth Division's move to the west and protecting the left flank of the 5th Cavalry Regiment. The 5th Cavalry, commanded by Col. Irving Lehrfeld, and the 7th Cavalry, under Col. Dan Gilmer, would attack abreast across the division front. The 8th Cavalry, with Col. Eugene J. Field in command, was the divisional reserve. All of the division artillery battalions would participate in the operation. The 61st and 82d Field Artillery Battalions, 105-mm.

and 155-mm. howitzers respectively, would support the 5th Cavalry, and the 77th and 99th (-) Field Artillery Battalions- both 105-mm howitzer- would support the 7th Cavalry. For general artillery support, I Corps made available to the 1st Cavalry division the following field artillery battalion units; the 936th Battalion (155-mm. howitzer); A Battery, 17th (8-inch howitzer) ; and A and B Batteries, 204th Battalion (155-mm. guns). The battalions were along the main line of resistance, 4 to 6 miles from Line JAMESTOWN.

An hour before the attack was launched, the artillery along the I Corps front began to soften up the enemy defense positions. Then at 0600 on 3 October the five UNC divisions moved out. In the 1st Cavalry Division sector the enemy response was immediate and violent. Task Force Mac on the left flank encountered heavy mine concentrations coupled with strong artillery and mortar fire; by the end of the day, it had made little progress. As Colonel Lehrfeld's 5th Cavalry assaulted the four intermediate hill objectives facing the regiment- Hills 222, 272, 346, and 287- the Chinese refused to give way. The enemy forces directed artillery and mortar fire at the 5th's three battalions as they labored up the hills, and as soon as the I Corps artillery lifted, the Chinese rushed out to their fighting positions and added heavy small arms, automatic weapons, and grenade fire to halt the attack. Six attempts by the 3d Battalion won a foothold on Hill 272, but enemy pressure forced a withdrawal later in the day. Only against Hill 222 could the 5th register any lasting success; after a frontal assault by the 3d Battalion, the Chinese had to abandon the hill and fall back to the north.

The situation in the 7th Cavalry's area to the east was quite similar. Attacking with the 3d, Greek, and 2d Battalions abreast, Colonel Gilmer's troops attempted to storm Hills 418 and 313 along with the ridge and high ground extending from these points. Both the Greek and the 2d Battalion won their way to the ridge line only to suffer heavy casualties from the Chinese counterattacks that followed; neither could hold on. Many positions changed hands three or four times during the course of the day as bitter hand-to-hand fighting marked the intensity of the enemy's resistance.

By the end of the first day, the supporting artillery had fired over 15,000 rounds at the enemy and the Chinese had committed the bulk of their 2d Artillery Division to help block the advance of the 1st Cavalry Division. The enemy's willingness to use most of his available artillery against the 1st Cavalry was accompanied by bolder employment of the artillery pieces in direct support and counterbattery roles. In the process enemy artillery locations were revealed and soon began to receive attention from both the I Corps artillery and Fifth Air Force fighter-bombers.

Despite heavy fighting on 4 October, there was little forward progress. Elements of the 8th Cavalry reinforced the 7th Cavalry on the right and assaulted the ridges west of Hill 418, but the enemy clung tenaciously to his positions. When he was driven off, he expended manpower freely to retake the lost ground. Each enemy company was using ten to twelve machine guns and large quantities of hand grenades. The latter caused the bulk of the 1st Cavalry Division's casualties as the close combat grew more bitter. During the day elements of the CCF 140th Division moved up to reinforce the 139th Division which had been hard hit by the 1st Cavalry's continued battering of the enemy positions. The 1st Cavalry, in its drive towards the Yokkok-ch'on and Line JAMESTOWN, now had to contend with the bulk of the elite 47th Army.

The first crack in the Chinese defense line came on 5 October, when the 1st Battalion, 8th Cavalry, discovered that the enemy had withdrawn from Hill 418 during the night. By afternoon the 1st Battalion cleared the ridge 1,400 yards to the northeast and was able to tie in with the 15th Regiment, U.S. 3d Division. The 2d Battalion, 7th Cavalry, then moved up the ridge southwest of Hill 418 and occupied Hill 313 without opposition. On the following day the 2d Battalion, 8th Cavalry, launched an attack on Hill 334, 2,260 yards west of Hill 418, and after two attempts, seized the objective. Heavy enemy counterattacks, day and night, were beaten back. At Hill 287, over 4,000 yards southwest of Hill 334, the 1st Battalion, 7th Cavalry, fought its way toward the crest and held on to part of the hill at nightfall. Prisoners of war taken on 5-6 October indicated that the Chinese were falling back on new prepared defense lines 57,000 yards to the northwest and that many units had been decimated in the opening days of the offensive; food and ammunition stocks, they also reported, were becoming exhausted.

On 7 October the 7th Cavalry completed the seizure of Hill 287 and sent the 3d Battalion to take Hill 347, a little over two miles southwest of Hill 418. Attacking from the south and southeast, the 3d Battalion began to clear the hill at the end of the day. The fall of Hill 347 meant that the 1st Cavalry now dominated the high ground comprising JAMESTOWN in the northeastern half of the divisional sector.

The breach in the northeast had little immediate effect upon the Chinese defense of the hills across the 5th Cavalry front, however, and the relentless hammering of artillery, mortar, and tank fire against the formidable bunker system failed to produce a breakthrough. Even air strikes with napalm and 1,000-pound bombs made little impression upon the enemy defenders, since the Chinese had constructed an intricate trench system and numerous escape routes that negated most of the effects of the air attacks. The dogged enemy defense- in many cases to the last man- took a heavy toll of 1st Cavalry Division forces and frequently produced a situation in which the American assault forces attained an objective in insufficient strength to resist the fierce enemy counterattacks that followed.

After eight days of UNC pressure against Hills 346, 236, and 272, the Chinese still refused to give ground. But the incessant punishment they had absorbed and the drain in manpower and ammunition stocks were beginning to tell. On the night of 12 October the Chinese abandoned Hill 272 and Colonel Field's 8th Cavalry troops took possession the next day without contact.

Control of Hill 272 opened the eastern approach to the key hill in the enemy's remaining defense line- Hill 346. On 15 October a new operational plan, called POLECHARGE, was put into effect. The 5th Cavalry was reinforced with the Belgian Battalion from the U.S. 3d Division and given the mission of taking Hill 346 and then pushing on to Line JAMESTOWN. The 8th Cavalry would move in from Hill 272 and if necessary assist the 5th Cavalry. Early on 16 October the assault got under way, but again the enemy firepower stopped the 5th Cavalry's advance. The 8th Cavalry's drive northeast of Hill 346 made some progress, yet could not flank the objective. For the next two days the 5th and 8th sustained the pressure on Hill 346 without success. Then on 18 October the 1st Battalion, 5th Cavalry, moved forward and took the hill against virtually no opposition. Hill 230 fell the same day to the 3d Battalion. By 19 October the 1st Cavalry Division had seized the last of its objectives on the JAMESTOWN line as the enemy retreated north of the Yokkok-ch'on to his next line of defense.

The sensitivity of the Chinese to the 1st Cavalry Division's advance toward their supply base at Sangnyong-ni did not end with the completion of COMMANDO. Although divisional patrols could range freely some 3-4,000 yards in front of the main line of resistance positions on the east, the enemy reacted strongly to every attempt to send probes and patrols across the Yokkok-ch'on towards Sangnyong-ni. During the COMMANDO operation, the Chinese had shown how valuable they considered the control of the terrain in this area. For the first time they had shifted from the fluid defense system that formed part of their basic tactical doctrine and had dug in in depth. The deep bunkers, complex system of trenches, and large stocks of food, supplies, and ammunition stored at the front-line positions showed that they intended to stay and defend in place. When the 1st Cavalry Division tried to storm the enemy's main line of resistance, the Chinese poured in firstclass reinforcements, freely expended their ammunition stocks, and fought fanatically to hold on. Only when losses in men and exhaustion of ammunition supplies forced them to withdraw, could the 1st Cavalry take possession of the JAMESTOWN line. Intelligence reports at I Corps headquarters pointed out that there seemed to be a definite lack of interest among the Chinese commanders in the fate of front-line regiments which had been ordered to resist to the end. According to the G-2 officers, this suggested that the Chinese might have come around to the belief that fewer troops would be lost through these tactics than in trying to retake lost territory with heavy counterattacks.57

In any case the cost to the enemy had been high. I Corps estimates of enemy losses during the 3-19 October period placed the total at well over 21,000 men, including over 500 prisoners. Close to 16,000 casualties had been inflicted upon the enemy by the 1st Cavalry Division alone, as it reduced the crack CCF 47th Army to half strength. But the I Corps had not escaped untouched; it had taken over 4,000 casualties during the 17-day operation, with the 1st Cavalry suffering over 2,900 of the total.58 In the process of absorbing losses the I Corps had improved its defensive position and kept the enemy from launching an offensive of his own.

While the I Corps sought to organize

103the gains Of COMMANDO, the U.S. IX Corps made plans to launch a similar operation toward Kumsong. On 9 October, General Van Fleet visited IX Corps headquarters and found Lt. Gen. William H. Hoge and his division commanders eager to carry out local advances along the corps front. The objectives would be to improve the defensive positions of the divisions in the line and to maintain pressure upon the enemy. Since both of these coincided with Eighth Army directives, Van Fleet gave his approval.59 In case of a successful IX Corps advance, however, there would be one disadvantage. The sag in the X Corps lines, which had just been eliminated, would be replaced by a bulge on the IX Corps' front.