History  On Line

On Line

On the eve of the opening of the substantive discussions at Kaesong, the Soviet Union launched a new peace offensive. The Russians suggested a fivepower peace pact to include Communist China and the banning of atomic weapons as steps that would lead to an easing of world tensions.1 As the United States was in the midst of preparations for the Japanese peace treaty conference and also currently negotiating defensive pacts with the Philippines, Australia, and New Zealand, the vague Russian proposals aroused little enthusiasm among the American leaders.2 The confluence of circumstances intimated that the Soviet peace drive was mainly inspired by a desire for favorable propaganda that might disrupt the American undertakings.

The dovetailing of the Communist peace movement with the armistice discussions did not cause any important alterations in the U.S. plans for concluding the treaty with Japan or the defensive pacts. Nor did it have any great effect upon the Korean negotiations. For the uncompromising position concerning the 38th Parallel adopted by the enemy delegates at Kaesong soon dispelled any illusion that they were eager for a truce except on their own terms.

The 38th Parallel

The search for a satisfactory formula for attaining a truce was hindered by the strong positions taken by both sides at the outset. As soon as the agenda was settled, General Nam quickly turned back to the 38th Parallel. Since the boundary had been recognized by all nations as the dividing line before the war, Nam urged that it be restored. Each side held territory north and south of the Parallel and neither would incur any great disadvantage by re-establishing the status quo. To create a demilitarized zone, Nam proposed that a 2o-kilometer strip along the parallel be cleared of troops. Such a realignment of forces and readjustment of territory would be fair and just, Nam maintained.3 The UNC rebuttal followed on 27 July. Admiral Joy ended the preliminary skirmishing and came out strongly in favor of a truce line based on battle realities rather than the 38th Parallel. Pointing out, that the Communist and U.N. forces had crossed the parallel no less than four times during the last thirteen months, he argued that this fact alone proved the unsuitability of the parallel as a demarcation line. An effective delineation of a demilitarized zone must be made on practical military grounds, Joy continued, and should not be influenced by consideration of ultimate political objectives; for a military armistice an imaginary geographical line such as the 38th Parallel had no validity whatsoever.

Ruling out the parallel as a line of demarcation, Joy advanced the UNC proposal. There were three battle zones to be considered, he maintained, the ground zone, the sea zone, and the air zone. Although the UNC forces occupied definite positions on the ground, they had superiority in the air over all Korea and controlled the entire Korean seacoast. Since the Communists would gain freedom of movement and be able to rebuild within their sector of Korea when the air and sea power of the U.N. Command were confined by a cease-fire and therefore would gain more than the U.N. Command through a truce, Joy suggested that the Communists should compensate the UNC by making concessions on the ground. On the map that he presented to the enemy delegates, UNC staff officers had drawn a demilitarized zone twenty miles wide considerably to the north of the ground positions then occupied by the UNC forces.4 This initial offer sought, of course, far more then the UNC delegates expected to secure, but even so, it was a novel approach- an attempt to break total military power into its component parts and give them separate values for bargaining purposes.

The Communist reaction was a swift and rude rejection. "Ridiculous," was Nam's comment on the 28th as he asserted that military power was the sum total of the power of all arms of the forces. The UNC battle lines, he went on, were the concentrated expression of the military effectiveness of its land, air, and sea forces. Although the present battle lines were variable, Nam felt that the 38th Parallel approximately reflected the current situation and should be accepted as the line of demarcation.

After rebuking Nam for his rudeness and bluster, Joy proceeded to defend the UNC proposal. Ground progress did not always indicate the status of a war, he contended, for Japan was defeated without a single soldier setting foot on the Japanese home islands.5

Nam refused to accept this statement. He derided the American claim that the United States had defeated Japan. Anyone knew, Nam said, that it was the Korean people's struggle, the Chinese people's war, and the Soviet Union's resistance that brought Japan to her knees. Had not the United States fought Japan for three years without victory until the Soviet Army entered the war and dealt Japan a crushing blow? "Can these historical facts be negated lightly?" he concluded.6

Since each side obviously was using a different history book, Admiral Joy did not pursue this subject. Instead he continued to point out the additional advantages that would accrue to the Communists if a truce was signed. They could repair their roads, bridges, and railroads, bring up supplies needed for the health and well-being of their troops, and restore and rehabilitate their towns and facilities.7

The Communists were not interested in the admiral's arguments. They clung steadfastly to the 38th Parallel as July passed by and the dog days of August began. The daily sessions became routine as each side presented the same arguments and refused to concede or compromise. Since apparently the support of Marshall and Acheson had helped convince the Communists that the United States would remain firm on the troop withdrawal issue, Joy suggested to Ridgway that high-level backing for the UNC position on Item 2 might also have a beneficial effect.8 He felt that the conference could break up over this matter for Nam would not even discuss a proposal not hinged on the 38th Parallel.9

In the midst of this impasse, a strange incident occurred. During the lunch hour on 4 August a fully armed company of Chinese troops marched past the UNC delegation house in clear violation of the neutrality of the conference zone. This was a double violation, in fact, for not only were there supposed to be no armed troops within a half mile of the conference site but also all troops within a 5-mile radius of Kaesong were to be equipped with sidearms only. When the conference resumed that afternoon, Joy immediately entered a strong protest and Nam promised to investigate.10

Whether the Communists wished to demonstrate their control of the conference site for propaganda purposes or simply made a mistake proved immaterial. General Ridgway decided to adopt a strong position and informed Kim Il Sung and Peng Teh-huai that the UNC delegation would not hold any further conversations with the Communists until a satisfactory explanation of the violation and assurances that it would not happen again were received.

The first reply from the Communists stated that the troops were guards responsible for police functions and that they had passed through the area by error. Instructions had been issued to prevent a recurrence. But although Admiral Joy recommended that the U.N. Command accept this response, Ridgway determined to press for an inspection team of equal representation to be organized and to carry out a full inspection of the entire neutral zone before the next meeting. Ridgway felt that the violation was either a deliberate attempt to intimidate or was due to gross carelessness or lack of discipline.11

On the morning of the 6th, a second message was broadcast in Korean, English, and Japanese by the Communists. Although the Korean and English versions were courteous and asked that the U.N. delegation return to Kaesong, the Japanese broadcast had an insolent and peremptory ending. Ridgway asked for permission to turn down the Communist explanation, but his superiors considered that the enemy had in effect accepted the UNC conditions. They instructed Ridgway to broadcast his acceptance and at the same time to warn the Communists that the resumption of the talks was conditional upon their complete compliance with the guarantees of the neutralization of the Kaesong area.12 Perforce Ridgway agreed, but he vented some of his indignation at the Communists in a message to Joy. Blasting the enemy as men who considered courtesy a concession and concession a weakness, he enjoined Joy to "govern your utterances accordingly and you will employ such language and methods as these treacherous Communists cannot fail to understand, and understanding respect."13

After a 5-day hiatus, the conference resumed on 10 August. Joy quickly informed General Nam that the UNC delegation was through discussing or considering the 38th Parallel as a military demarcation line. Immediately the Communists protested against this attempt to limit the discussion, but Joy soon pointed out that his stand governed only the UNC response and in no way prevented the Communists from talking about the 38th Parallel. A very curious interlude ensued. For two hours and ten minutes the two delegations faced each other in frozen silence punctuated only by the occasional nervous tapping of Nam's cigarette lighter on the table. Finally Admiral Joy broke the sound barrier and suggested that the conferees turn to Item 3, since no agreement could be reached on the line of demarcation. The Communists refused.14

Again General Ridgway urged his superiors to support a strong course of action. He proposed to give the Communists seventy-two hours to modify their adamant position. If they still would not budge, then they would be told that by their own deliberate act they had terminated the negotiations. But the Washington leaders disapproved. They had no intention of presenting an ultimatum at this stage of the discussions. If and when the conferences were broken off, the onus should fall squarely upon the Communists. After all, they pointed out, the 38th Parallel might not be the breaking point and it would take time for Moscow and Peiping to amend their stand. Past experience in dealing with the Communists had shown that long and protracted discussions were standard procedure. Calmness, patience, perseverance, and firmness should characterize the U.N. delegation attitude. This approach, they concluded, would subject the enemy to the greatest strain while sustaining the unity and strength of the UNC position.15

On 12 August the Communist representatives returned to the attack. "You should know that truth is not afraid of repetition, and needs repetition," admonished General Nam as he argued the case for the 38th Parallel. Unfortunately there was no common agreement on what "truth" was or whose "truth" was more "truthful" than the other's. Nam termed the U.N. proposal for ground compensation "absurd and arrogant" and his own as "reasonable," while Joy attacked the Communists' "inflexible and unreal stand" and defended his own "reasonable" procedure.16 Since neither side wished to show any sign of weakness nor to make concessions without a quid pro quo, the sparring in the battle of words continued for several days with no progress.

The Communists fought hard against a land advance of the UNC forces as compensation. As Pravda put it, "The Korean people have not agreed to the negotiations in Kaesong in order to make a deal with the American usurpers over their own territory."17 But although the UNC delegation admitted that its proposed demarcation line was entirely within the Communist-controlled area and offered to make some territorial adjustments based on the current battle line and over-all military situation, it held firmly to the concept of compensation.18

Finally in an effort to break the deadlock, Admiral Joy made an important suggestion that was to have a considerable effect upon the conduct of the negotiations. On 15 August he proposed that a subcommittee of one delegate and two assistants from each side be formed. He believed that a less formal round-the-table exchange might be conducive to freer discussion and might produce a feasible plan for solving Item 2. On the following day the Communists accepted, but not without raising the number of delegates to two instead of one. They nominated Generals Lee and Hsieh, and Joy named General Hodes and later Admiral Burke, as his representatives. While the subcommittee attempted to work out its recommendations, the plenary meetings would stand in recess.19

The first subdelegate discussion took place on 17 August, and although no concrete progress resulted, the atmosphere was more relaxed. General Hsieh seemed to like this type of exchange. He spoke frequently and acted as a moderator when the comments became sharp. As the talk flowed back and forth around the small table, there was even a tendency on the part of the Communists to consider the demarcation line on the map.

At the second session the UNC delegates managed to shock the Communists by offering to toss a coin to decide which side should make the first new proposal. The Communists could not imagine having an important point turn on the flipping of a coin. Nevertheless they did bring forth a map that slightly modified their stand on the 38th Parallel. On the east they gave the U.N. Command about four kilometers and they took about the same amount in western Korea. Later they went further. They proposed to do away with all previous maps and to start afresh. Although they refused to answer several pointed questions on the 38th Parallel, General Hodes and Admiral Burke felt that the Communists might be ready to discuss other solutions, provided that the U.N. Command made the opening gambit.20

When the third session convened on the 19th, Hodes suggested that, for discussion purposes, the conferees assume that all air and naval effectiveness was reflected in the battle line. The Communists were willing to talk on this basis, but warily waited for the U.N. Command to make a definite new proposition. After two days of fruitless fencing, the Communists retreated further from their position on the 38th Parallel. They indicated that if the U.N. Command would give up the concept of compensation, they would present a proposal based upon adjustments along the battle line. Since this was a definite step forward, the UNC delegates agreed to the principle of adjustment. The meeting of the 22d adjourned with the possibility of agreement much closer at hand.21

General Ridgway was encouraged. Anticipating that the Communists might be willing to discuss the "line of contact" as opposed to the "general area of the battle line," he asked and secured approval for his plan to settle on a demilitarized zone not less than four miles wide with the line of contact as the median.22

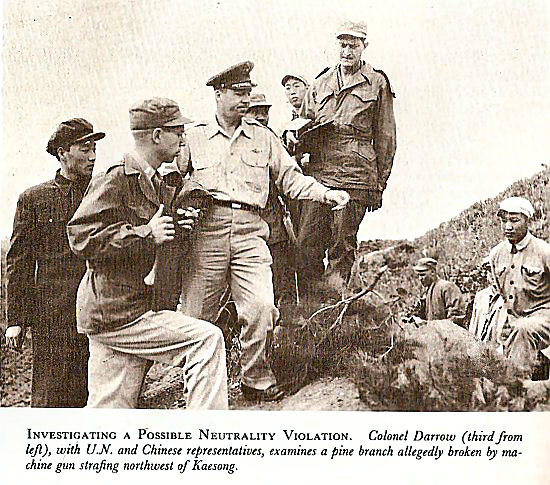

Unfortunately the promise of progress in the subdelegation meetings was shortlived. A succession of incidents stemming from alleged violations of the neutral zone around Kaesong led the Communists to call off the meetings on the night of the 22d.

The Incidents

Charges and countercharges of violations of the conference area and of the neutrality arrangements had been rampant from the outset of the negotiations. Following the Communist refusal to admit the UNC newsmen, the UNC delegation had insisted upon an agreement on rules and regulations governing the conference area. In brief this established a neutral zone with a 5-mile radius centered on the traffic circle in Kaesong. Each side agreed to refrain from hostile acts in this zone and all military forces except those performing and equipped for military police functions would be withdrawn. No armed personnel would be stationed within a half mile of the conference house. During daylight hours the U.N. delegation was given unrestricted use of the road between Panmunjom and Kaesong without prior notification of the Communists. The U.N. liaison officers had already informed their counterparts at the first meeting on 8 July that Communist convoys to and from Kaesong, if marked with white crosses and if the U.N. Command was alerted as to their time and route, would not be attacked. These arrangements seemed fairly clear and simple, yet alleged infractions were charged almost at once.

On 16 July the Communists claimed that UNC soldiers had fired in the direction of Panmunjom. Although no one was injured or any damage committed, the Communists stated that this was an act of armed force within the neutral zone. Investigation by the U.N. Command showed that some firing in the general area of Panmunjom had taken place, but no evidence indicated either that the fire had entered the neutral zone or that the UNC forces had done the firing.23 In any event, the Communists did not pursue the matter.

Five days later Col. Chang Chun San, the North Korean liaison officer, informed Colonel Kinney that UNC planes had strafed the Communist delegation's supply trucks marked with white flags at Hwangju and Sariwon. But since the Communists had not notified the UNC of the movement of this convoy, the U.N. Command refused to assume any responsibility for damages incurred under such circumstances. With the enemy using the roads between P'yongyang and Kaesong to build up his strength, Ridgway did not intend to extend blanket immunity to all vehicles bearing white markings, for the UNC suspected that the Communists might well use this device to slip through men and materiel for the front. Furthermore, the U.N. Command had to take the word of the Communists that a strafing had actually occurred, for no investigations were carried on outside the conference area. Ridgway told Admiral Joy to inform the enemy that unless advance warning was given, vehicles would be attacked wherever found.24

The first two incidents were relatively minor and the Communists did not raise too much fuss over them. It may have come as quite a shock or revelation to them when the U.N. Command strongly protested against the already mentioned violation of the conference area by a company of fully armed Chinese Communist troops on 4 August and suspended the meetings for five days until satisfactory assurances against recurrence were received from Generals Kim and Peng. With the U.N. Command garnering favorable publicity from the incident and putting the Communists on the defensive, the enemy may have decided to launch a counteroffensive.

On 8 August, while the recess continued, the Communists reported that two UNC violations of the neutrality arrangements had been committed the previous day. First, UNC planes had assaulted a supply truck marked with a white flag at Sibyon-ni, and, second, about forty UNC troops had closed on the bridge at Panmunjom and several had fired at unarmed Communist personnel. Again, but without much success, the UNC liaison officers patiently tried to convince their opposites that prior notification of convoy movements was the only guarantee of immunity. The Communists insisted that the white markings were sufficient. After a thorough investigation of the second charge, Admiral Joy found that no UNC units had been in the Panmunjom area at that time and therefore could not have been responsible for the shooting. Because of a delay of twenty-eight hours by the Communists in laying this claim, Joy questioned its validity.25

Less than a week later, on 13 August, another strafing attack on three Communist supply vehicles took place in the vicinity of Sibyon-ni and again the enemy protested. Admiral Joy's acknowledgement was brief and stated in part: "In view of the fact that no notification of this movement was received, no action on the part of the United Nations Command is neccessary and none is contemplated."26

The spate of incidents led the Communists to request that the liaison officers meet and work out more satisfactory arrangements. In mid-August Colonel Kinney and Col. James C. Murray (a Marine Corps officer) held a series of conferences with Colonel Chang and reached agreement on a number of items. But even as they sought to attain final accord, several new incidents occurred.

One was another truck strafing, but the second was of a more serious nature. On 19 August a Chinese military police platoon, patrolling near the village of Songgong-ni in the neutral zone, was ambushed and the platoon leader was killed and another soldier wounded. The Communists immediately protested and accused the U.N. Command of breaching the old agreement. While the UNC officers investigated the charge, the enemy made the most of the incident. In the subdelegation meeting on the 20th, the Communist representatives recessed the session early so as to attend the funeral of the platoon leader and invited General Hodes and Admiral Burke to go along with them. This placed the UNC delegates in an embarrassing position, for if they accepted, the Communists would be sure to take pictures and publicize and probably distort the reasons for their presence. Hodes and Burke decided to decline and hastened to their helicopter at the close of the meeting. Somewhat apprehensive lest the Communists stop them en route and escort them to the last rites, they made it safely to the plane and took off as quickly as possible for Munsan-ni.27

Despite conflicting testimony, investigation showed that the patrol had been ambushed, but that no U.N. or ROK units had been close to Songgong-ni at that time. Since some witnesses stated that several members of the attacking force had worn civilian clothes and had been seen in the area before, the UNC officers surmised that they were partisans friendly to the ROK but acting independently.28 Needless to say, the Communists were not satisfied with this explanation and made full use of the incident for propaganda purposes.

Before the furore caused by this episode had died away, the Communists summoned Colonel Kinney from his bed in the early morning hours of the 23d to lodge another protest. Upon his arrival at Kaesong, Colonel Chang and his Chinese colleague, Lt. Col. Tsai Cheng-wen, informed him excitedly that a UNC plane had bombed the conference site. Despite the darkness and a driving rain, Kinney and his associates inspected the evidence. Although there were several small holes, the so-called bomb fragments appeared to be parts of an aircraft oil tank and an engine nacelle. The Communists claimed that one of the bombs had been napalm, but nowhere was there any badly scorched earth area that a napalm explosion would have caused. After viewing the evidence, Kinney termed the whole affair "nonsense."

Whereupon Chang retorted that "all meetings from this time" were called off.

As the UNC party drove to Panmunjom, the Communist liaison officers overtook them and urged them to return and complete the investigation. Kinney preferred to wait until daylight but Chang and Tsai insisted that new evidence had been uncovered. Reluctantly Kinney returned and was shown two more small holes, several small burned patches, and some pieces of aircraft metal. There was an odor of gasoline and a substance in one of the holes might have been a low-grade napalm that had not been ignited. When the U.N. investigators requested that all the evidence remain in place until it could be inspected by daylight, the Communists refused. They intended to gather it all for analysis and considered the investigation over.29

There were many elements in this affair that pointed to a deliberate attempt on the part of the Communists to arrange an incident to suspend the negotiations. In the first place, the Fifth Air Force maintained that it had no planes up in the area. Secondly, the plane that supposedly dropped the bombs had its headlights on, a procedure contrary to all UNC practice. Thirdly, the bomb pattern of the craters was such that, in the opinion of the UNC investigators, no single plane could have made them. In addition to these technical objections and the flimsiness of the evidence, the haste of the Communists and their eagerness to gather in the fragments for analysis and the quickness with which the low-echelon liaison officer was able to call off the meetings made the Communist motives suspect. As Ridgway informed the JCS, this decision must have been made in advance and at the highest level. As he saw it, there were three possible reasons for the Communists action: 1. They wanted an excuse to break off the negotiations, with the blame falling on the UNC. 2. They wanted to stall to mesh the timing of the conference talks with the Japanese peace treaty and the Russian peace offensive. 3. They desired a suspension to strengthen their propaganda position and to regain the initiative in the negotiations.30

Ridgway's suggestions did not exhaust the list. There were several other interesting variations. Disappointment in the failure of the United States to invite Communist China to the San Francisco peace conference on Japan was one suggestion at the time. Another theory reasoned that the Communists had thought the UNC proposal for subdelegation meetings meant that the U.N. Command was ready to compromise on the 38th Parallel and when this hope proved false, decided to play for time while they worked out their next move.31

Whatever the motivations might be, the truce talks entered a long period of suspension. The UNC rejection of responsibility for the bombing of Kaesong elicited many angry Communist responses but the UNC held firm. In the meantime the Communists entered several new charges of UNC violations. They claimed that a UNC plane had dropped a flare in the Kaesong area on 29 August; that UNC forces had attacked a patrol and fired shots across the bridge at Panmunjom on 30 August; and that UNC planes had bombed Kaesong a second time on 1 September. Investigation of these charges by UNC officers revealed that no UNC planes could have committed the air incidents and that partisan forces were probably responsibile for the ground action.32

Both Ridgway and Joy felt strongly that the best way to lessen the possibility of further incidents was to change the negotiation site. The former had recommended that a new location be proposed in early August and after the avalanche of incidents during that month, Joy reinforced him stoutly. The U.S. leaders

were willing to have the U.N. Command put forward a suggestion, but at this point they did not wish to make a change in site a mandatory prerequisite to a resumption of negotiations.33

The one encouraging factor lay in the Communists' willingness to continue the battle of words over the violations. If they seriously intended to break off the negotiations completely, they had created a situation in which they could have withdrawn and blamed the U.N. Command. Despite the lack of substance in most of their accusations, they had seized the propaganda initiative and forced the UNC on to the defensive. The U.N. Command could calmly refute the Communist claims again and again, but the flood of incidents tended to obscure the denials. However as September wore on, there were indications that the Communists had attained their objective, whether it was time or the initiative, and were prepared to reopen negotiations.34

Strangely enough, the occasion was another incident, only this time it was a real violation of the neutral zone. On 10 September a plane from the 3d Bomb Group strafed Kaesong through a navigational error by the pilot. Fortunately no damage was incurred, but the Communists entered a formal protest. As soon as the investigation disclosed that a UNC plane had committed the attack, Admiral Joy wrote and apologized for the infraction. This drew what could be considered almost a friendly response from the Communists on 19 September. In view of the UNC willingness to assume responsibility for this violation, Kim and Peng suggested to Ridgway that the delegates resume the negotiations at Kaesong immediately.35

But Ridgway was unwilling to reopen the negotiations until there was a definite improvement in the physical setup. The Communists had previously brushed aside his suggestion that the site be changed, but he determined that the conditions for a resumption must be settled at the liaison officer level and not by the delegates. At the same time he intended to press for a new location36

Communist opposition to any change in the site and to the liaison officers working out the details of neutralizing the truce zone threatened to lengthen the recess. The Communists were reluctant to give their liaison officers the authority necessary for coming to an agreement on either point. Nevertheless, Kinney reported after the first meeting of the liaison officers on 25 September that they seemed anxious to get the delegation together. He felt that patience and firmness would finally gain the establishment of satisfactory conditions.37

In Washington, intelligence sources were reluctant to attach any special significance to the signs of Communist anxiety. Since the Communist position in Korea had not deteriorated, they held that no new line of action seemed imminent and that the Russians may have directed a resumption for their own military or political purposes.38

In any event Ridgway and his staff drew up a plan of action. Since Chairman of the JCS General of the Army Omar N. Bradley and State Department Counselor Charles E. Bohlen were in the Far East, Ridgway submitted his proposed policy to them and secured their approval. The plan posed three alternatives based on Communist reactions. If they accepted a change of site, the UNC delegation would offer a 4-kilometer demilitarized zone based generally along the line of contact. As long as the Communists clung to Kaesong but no break seemed imminent, the U.N. Command would push for a new site without categorically excluding Kaesong. The third alternative would rise if a break seemed likely: the U.N. commander would send a message with a map to the Communists indicating the proposed demilitarized zone and subdelegations would be suggested to discuss this at a place acceptable to both sides.39 Bohlen later reported that Ridgway and his staff felt that the U.N. Command had made steady concessions to the Communists on procedural matters and had possibly created an appearance of weakness that the military situation did not justify. Bohlen recommended that Ridgway be firmly supported on the matter of a new site even though it seemed to him to be an artificial issue.40

While Ridgway pursued his pressure campaign, exchanging letters with Kim and Peng on the higher level and backing a staunch stand at the liaison officers meetings, several new incidents took place. On 19 September a South Korean invasion of the neutral zone occurred. Four unarmed ROK soldiers with full Red Cross insignia lost their way and crossed the bridge at Panmunjom on a truck loaded with DDT. The bewildered health team and the truck were immediately taken into custody, no doubt on suspicion of conducting biological warfare, and were only released upon the signing of a receipt by the UNC liaison officers.41

On 7 October a UNC B-26 crossed the neutral zone, but no attack was made. The crew was officially reprimanded for the overflight. Five days later a more serious violation drew a strong protest from the Communists. On 12 October a flight of UNC F-80's passed over the neutral area en route home. One of them cleared its machine guns and accidentally killed a 12-year-old Korean boy and wounded his 2-year-old brother. Although the U.N. Command accepted the responsibility for this unfortunate affair and tendered its deep regrets, the atmosphere at the liaison officers meeting underwent a sudden change.42

Until this latest episode progress had been encouraging. The patience and firmness of the U.N. Command had won several concessions from the Communists. Under steady pressure the latter had at last consented on 7 October to a transfer of the site from Kaesong to Panmunjom, where both sides would assume responsibility for protecting the conference area.43 Ridgway immediately instructed Van Fleet to be ready to take over the high ground east of Panmunjom as soon as final arrangements for the reopening of negotiations were concluded.44

When the liaison officers met on 10 October, the Communists refused initially to discuss anything but the time and date of the next meeting of the delegates. Colonel Chang was rather abrupt in his treatment of the UNC officers, but the Chinese liaison officer, Colonel Tsai, intervened and smoothed over the situation. He accepted the documents and map of the neutral area offered by Colonel Murray and later escorted Murray to the door of the tent while his senior, Chang, stood silently by.45 Such an overt action by the junior officer provided a good example of where the real power lay.

As soon as the Communists realized that the U.N. Command was not going to hold a meeting on higher level until the liaison officers established the rules and regulations, they reluctantly agreed to work out the details at the staff conferences. Relations between the lower echelons had become comparatively cordial and prospects for quick agreement on the conditions for resumption appeared bright when the 12 October incident cast its shadow. Overnight the Communists reverted to the old frigid formality and tempers grew short. The following exchange between Kinney and Chang during a long and trying session on the 16th was symptomatic of the new climate of opinion:

Kinney: I find that is is becoming a habit of Colonel Chang to read me a lesson on how to conduct my portion of this particular discussion.

Chang: It seems to me that Colonel Kinney is worrying about things about which he should not worry. Inasmuch as I am not in a position of being an instructor of Colonel Kinney, I have no responsibility for educating him.

Kinney: I am glad that you realize that.46

Despite this turn in the personal relationships, the points of official differences narrowed. Since the site was moving to Panmunjom, the U.N. Command wished to limit the neutral area around Kaesong to 3,000 yards rather than five miles. Such a contraction would lessen the area in which incidents could occur. But the Communists fought this proposal strongly and would not agree to delimitation below three miles. The UNC representatives finally compromised and accepted this figure both for Kaesong and the U.N. base camp at Munsanni.47

Map 2. The Armistice Conference Area, 22 October 1951A second important item that blocked final agreement concerned the violations of the air space over the neutral zone. After the many instances of UNC planes flying over the area through navigational error or because of the weather conditions, the UNC negotiators wished to eliminate accidental invasion of the air space as a violation. The Communists insisted for some time that this was a hostile act of armed force, but at last agreed to compromise and recognized that there might be weather and technical conditions beyond human control under which aircraft might fly over the conference area but without any intent to attack or damage it.48

On 22 October the liaison officers signed the new security agreement which embodied most of the features desired by the U.N. Command. Besides the restriction of the Kaesong area to three miles and the provision on accidental overflight of the neutral zone, the UNC was also able to except itself from responsibility for the acts committed by irregulars or partisans not under its control. This had been another troublesome matter and the cause of several Communist complaints in the past. A 1,000-yard circle around Panmunjom was neutralized as was a 200-meter area on each side of the road from Kaesong to Panmunjom to Munsan. (Map 2) In the Panmunjom area each side agreed to station 2 military police officers and 15 men armed with small arms while the conference was in session and 1 officer and 5 men during other periods. The Communists offered to supply the delegation conference tent and the U.N. Command to provide flooring, space heating, and lights for the tent. Other wise each side would take care of its own needs in the conference area. To help prevent violations of the air space, the U.N. Command agreed to set up a searchlight and barrage balloons at Panmunjom.49

Having secured the agreement, the UNC delegates hoped to steal a march upon the Communists. Admiral Joy anticipated that the Communists intended to discuss the security arrangments all over again at the delegate level, so he dispatched a letter to Nam ratifying the liaison officers' accord and told Nam that he would await the Communist concurrence before resuming negotiations. Colonel Kinney also informed Chang that UNC security troops were moving in to the high ground east of Panmunjom to eliminate the possibility of incidents from this quarter.50

General Nam signed the Communist ratification on 24 October and the first meeting of the delegates was scheduled for the following day. Thus after two months the truce conference resumed, but what had happened in the meantime? There seemed little doubt that the Communists had regained the propaganda initiative. Despite the staged incidents and the question of validity of others, there had been enough actual violations to provide the leaven for the Communist case. If this were the Communist objective in suspending the meetings, the mission had been successfully accomplished. But if the Communists had hoped to alter the UNC position on the 38th Parallel and secure substantial concessions by this propaganda campaign, they had failed. Their action had only strengthened the UNC determination not to concede.

On the other hand the Communist tactics had several by-products. The delay in the negotiations led to increased UNC pressure on the battlefield and in the air. It provided time for additional training of the South Korean forces and for the National Police Reserve in Japan. And it also allowed the United States ample opportunity to consider the shortand long-range situations in the Far East.

Notes

1 Other members of the pact would be the United States, United Kingdom, USSR, and France.

2 See article of the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, Warren R. Austin, "International Unity Against Shifting Soviet Tactics," in Dept of State Bulletin, vol. XXV, No. 637 (September 10, 1951), pp. 425ff. See also New York Times, August 7, 1951.

3 Transcript of Proceedings, Tenth Session, Conf at Kaesong, 26 Jul 51, in FEC 387.2, Korean Armistice Papers, Min of Conf Mtgs.

4 Ibid., Eleventh Session, 27 Jul 51.

5 Ibid., Twelfth Session, 28 Jul 51.

6 Ibid., Thirteenth Session, 29 Jul 51.

7 Ibid.

8 Msg, HNC 148, Joy to Ridgway, 28 Jul 51, in FEC 387.2, bk. I, 45-D.

9 Msg, HNC 175, Joy to Ridgway, 4 Aug 51, in FEC 387.2, bk. 1, 60-C.

10 Transcript of Proceedings, Nineteenth Session, Conf at Kaesong, 4 Aug 51, in FEC 387.2, Korean Armistice Papers, Min of Conf Mtgs.

11 Msg, C 68881, Ridgway to Joy, 6 Aug 51, in FEC 587.2, bk. 1, 65.

12 Msg, JCS 98216, JCS to CINCFE, 6 Aug 51.

13 Msg, C 68554, Ridgway to CINCUNC (Adv), 8 Aug 51, in FEC 387.2, bk. I, 68-A-1.

14 Transcript of Proceedings, Twentieth Session, Conf at Kaesong, 10 Aug 51, in FEC 387.2, Korean Armistice Papers, Min of Conf Mtgs.

15 (1) Msg, C 68672, CINCFE to JCS, to Aug 51. (2) Msg, JCS 98637, JCS to CINCFE, 11 Aug 51. Msg, JCS 98713, JCS to CINCFE, 11 Aug 51. All in FEC 387.2, bk. I, 72.

16 Transcript of Proceedings, Twenty-second Session, Conf at Kacsong, 12 Aug 51, in FEC 387.2, Korean Armistice Papers, Min of Conf Mtgs.

17 Quoted in Carl Berger, The Korea Knot: A Military-Political History (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1957), p. 144.

18 Transcript of Proceedings, Twenty-third and Twenty-fourth Sessions, Conf at Kaesong, 13, 14 Aug 51, in FEC 387.2, Korean Armistice Papers, Min of Conf Mtgs.

19 Ibid., Twenty-fifth and Twenty-sixth Sessions, 15, 16 Aug 51.

20 Summary of Proceedings, First and Second Sessions, Subdelegation Mtgs on item z, 17, 18 Aug 51, in FEC 387.2, Korean Armistice Papers, Subdelegation Mtgs.

21 Ibid., Third and Sixth Sessions, 19, 22 Aug 51.

22 (1) Msg, C 69346, CINCFE to JCS, 21 Aug 51, in FEC 387.2, bk. II, 109 (2) Msg, JCS 99477, JCS to CINCFE, 22 Aug 51.

23 Rpt of Investigation, Col James C. Murray for CINCUNC, sub: Rpt of Investigation Alleged Violation of Neutral Zone, 18 Jul 51, in FEC 887.2, Korean Armistice Papers, Rpts of Investigation.

24 (1) Msg, HNC 133, CINCUNC (Adv) to FEAF, 25 Jul 51. (2) Msg, CX 67744, CINCFE to CINCFE (Adv), 26 Jul 51. Both in FEC 387.2, bk. I, 35.

25 (1) Rpts of Investigation, sub: Summary of Protest and Replies Concerning Alleged Violation of 7 Aug 51, no date, in FEC 387.2, Korean Armistice Papers, Rpts of Investigation. (2) Msg, CX 68595, CINCFE to JCS, 9 Aug 51, in FEC 387.2, bk. I, 71.

26 Ltr, Joy to Nam, 14 Aug 51, no sub, Tab 7 in Rpt of Investigation, sub: Summary of Protest . . . Strafing at Sib Yon Ni, no date, in FEC 387.2, Korean Armistice Papers, Rpts of Investigation.

27 Interv, author with Col Howard S. Levie, Staff Officer for Subcommittee on item 2, 7 Mar 58. In OCMH.

28 Rpt of Investigation, sub: Summary of Protest . . . 19 Aug 51, Communist Patrol Ambushed, Communist Truck Attacked, in FEC 387.2, Korean Armistice Papers, Rpts of Investigation.

29 Rpt of Investigation, sub: Summary of Protest and Replies . . . Bombing of Kaesong, no date, in FEC 387.2, Korean Armistice Papers, Rpts of Investigation.

30 Msg, CX 69566, CINCFE to JCS, 24 Aug 51, in FEC 387.2, bk. II, 116.

31 William H. Vatcher, Jr., Panmunjom: The Story of the Korean Military Armistice Negotiations (New York: Frederick A. Praeger, Inc., 1958) , pp. 66-67.

32 Rpts of Investigation, sub: Summaries of Protest and Replies . . . Flare Dropped Over Kaesong, etc., no dates, in FEC 387.2, Korean Armistice Papers, Rpts of Investigation.

33 (1) Msgs, HNC 264 and HNC 272, CINCUNC (Adv) to CINCFE, 24, 28 Aug 51, in FEC 387.2, bk. II, 118-B and 121-B (2) Msg, C 50115, CINCFE to JCS, 3 Sep 51, in FEC 387.2, bk. II, 131-B. (3) Msg, JCS 80658, JCS to CINCFE, 5 Sep 51, in FEC 587.2, bk. II, 135.

34 On 8 September, 48 of the 51 nations which had been at war with Japan signed the peace treaty at San Francisco. Only the USSR, Poland, and Czechoslovakia failed to sign. The successful conclusion of the treaty may also have influenced the Communists to resume negotiations.

35 (1) Msg, CX 50634, CINCFE to JCS, 11 Sep 51. (2) Ltr, Joy to Nam, no sub, 11 Sep 51. (S) Ltr, Kim 11 Sung and Peng Teh-huai to Ridgway, no sub, 19 Sep 51. All in FEC 887.2, Korean Armistice Papers, Rpts of Investigation.

36 Msg, C 51315, CINCUNC to JCS, 21 Sep 51, in FEC 387.2, bk. II, 147-A.

37 (1) Msg, HNC 815, CINCUNC (Adv) to CINCUNC, 24 Sep 51, in FEC 887.2, bk. II, 150. (2) Msg, HNC 323, CINCUNC (Adv) to CINCUNC, 25 Sep 51, in FEC 387.2, bk. II, 159.

38 JCS 1776/253, 25 Sep 51, title: Evolution of Recent Developments Pertaining to Cease-Fire Talks in Korea.

39 Msg, Ridgway to JCS, 1 Oct 51, DA-IN 2201.

40 Memo, Bohlen for Secy State, 4 Oct 51, sub: Rpt on Trip to Japan and Korea with General Bradley, in G-3 333 Pacific, 12.

41 Msg, HNC 309, CINCUNC (Adv) to CINCFE, 19 Sep 51, in FEC 387.2, bk. II, 146-B.

42 (1) Msg, A 4757 CG FEAF to CINCFE, 12 Oct 51, in FEC 387.2, bk. III, 184. (2) Msg, HNC 353, CINCUNC (Adv) to CINCFE, 12 Oct 51, in FEC 387.2, bk. III, 199. (3) Msg, HNC 359, CINCUNC (Adv) to CINCFE, 14 Oct 51, in FEC 387.2, bk. III, 203.

43 Msg, CX 52498, CINCFE to JCS, 8 Oct 51, in FEC 387.2, bk. III, 179.

44 Msg, CX 52506, CINCFE to CG Eighth Army, 8 Oct 51, in FEC 587.2, bk. III, 188.

45 Msg, HNC 849, CINCUNC (Adv) to CINCFE, 10 Oct 51, in FEC 387.2, bk. III, 189.

46 Memo for Rcd, 16 Oct 51, sub: Liaison Officers' Mtg Held at Panmunjom, in FEC 387.2, Korean Armistice Papers, Liaison Officers Mtgs.

47 (1) Msg, C 53096, CINCFE to JCS, 16 Oct 51, in FEC 387.2, bk. III, 206. (2) Msg, HNC 374, CINCUNC (Adv) to CINCFE, 20 Oct 51, in FEC 887.2, bk. III, 213.

48 (1) Msg, HNC 374, CINCUNC (Adv) to CINCFE, 20 Oct 51, in FEC 387.2, bk. III, 213. (2) Msg, HNC 376, CINCUNC (Adv) to CINCFE, 21 Oct gi, in FEC 387.2, bk. III, 215.

49 Memo for Rcd, Liaison Offcers' Mtg Held at Panmunjom, 21, 22 Oct 51, in FEC 387.2, Korean Armistice Papers, Liaison Officers Mtgs.

50 Msg, HNC 381, CINCUNC (Adv) to CINCUNC, 22 Oct 51, in FEC 387.2, bk. III, 220.

Causes of the Korean Tragedy ... Failure of Leadership, Intelligence and Preparation