History  On Line

On Line

Amid rumbles of ROK discontent and the mounting roar of Communist cannon warning of the impending offensive at the front, the plenary session of the truce conference reconvened at Panmunjom on 10 July. The ominous signs in the background were offset somewhat by the simple fact that the enemy was willing to resume the armistice discussions. After the ROK President had effected the release of the Korean nonrepatriate prisoners, the Communists might well have broken off the talks completely on the grounds that the U.N. Command had not kept faith with the tentative understandings already reached. Nevertheless, they had returned. Whether they now intended to use the negotiations as a forum for their complaints on this score or earnestly desired to conclude the arrangements for a cease-fire could not be presaged, but at least the possibility of a settlement had not been entirely ruled out. If the Communists proved to be seriously interested in finishing the military phase of their Korean experiment, the chief task of the United Nations Command delegation might well be to allay the misgivings of the enemy over the future conduct of the government of Syngman Rhee.

Assurances and Reassurances

General Clark was well aware of the problem. Before the truce teams met at Panmunjom, he asked his superiors in Washington for confirmation of the power granted him in late June to terminate the conflict with or without assurances of co-operation from the ROK Government. The reply on 8 July reaffirmed his authority but, at the same time, cautioned him against implying to the Communists that the UNC would employ force to insure ROK compliance with an armistice.1

Since the U.N. Command could not guarantee that it would use force if necessary to prevent the ROK forces from violating the truce, Clark approached the question from another direction. On 9 July he suggested to the JCS that if Harrison were pressed by the Communists, the senior delegate might inform them that the UNC would immediately withdraw all logistical and military support from any ROKA unit that sought to contravene the armistice through aggressive action. General Collins quickly advised him that the State Department objected to such a commitment since it would restrict Clark's freedom of action.2 Thus, on the eve of the resumption of plenary sessions, Clark and Harrison found themselves in an awkward situation. The only answers that they could offer to the specific and pointed questions certain to be posed by the enemy would have to be phrased in vague and general terms.

The first plenary conference exposed the weakness of the UNC position.3 In his opening statement Nam Il harked back to Clark's letter on 29 June to Kim and Peng. He wanted to know what steps had been taken to recapture the prisoners released by Rhee and what measures had been adopted to prevent further moves by the ROK Government in the same vein. Did the armistice include the ROK Government and Army, he went on, and what guarantees could the UNC provide to insure that the South Korean forces would abide by its terms? In view of the inflammatory statements made by Rhee against both the personnel of the United Nations Commissions and the Communist side, how could the UNC protect these people in the pursuit of their postarmistice responsibilities, Nam continued. "If an armistice does not include the South Korean Government and Army, the war in Korea will not actually stop even if the representatives of the United Nations Command undertake to sign the Korean Armistice . . . . Therefore, in order to insure that the Armistice Agreement can become truly effective, your side has the inescapable responsibility for putting forward concrete and effective measures in regard to the various questions mentioned above and putting them into effect," he concluded.

In his reply Harrison could only state:

We assume that Republic of Korea Forces presently under the command of the United Nations Command will remain so after an armistice and that they will carry out the instructions of the United Nations Command and withdraw from the part of the demilitarized zone in which they are now deploying in accordance with the Armistice Agreement.

As stated in General Clark's letter of 29 June, the United Nations Command will make every effort to abide by the provisions of the Armistice Agreement. We cannot guarantee that the Republic of Korea Government will lend full support to it, but the United Nations Command shall continue to do everything within our power to cause them to cooperate.

Harrison went on to promise police protection for the members of commissions and Red Cross teams to insure their safety. Then, using the risk factor presented by ROK opposition, he took the opportunity to bring up the suggestion that all the nonrepatriate prisoners be moved to the demilitarized zone and turned over to the Neutral Nations Repatriation Commission. Although this would impose heavy logistical burdens upon the U.N. Command, Harrison declared that the commission personnel could operate unmolested in the demilitarized zone. Possibly this matter could be handled after the armistice through the Military Armistice Commission, he said.4

While the Communists studied the UNC statements, Harrison and Clark sought to strengthen their position at the conference. Harrison had been encouraged by the attitude of the enemy delegation during the meeting. The questions asked by the Communists had been logical and pertinent and their behavior was calm, matter of fact, and not aggressive, he reported. In view of the reasonable approach of the Communists, both he and Clark felt that they should offer more concrete assurances at the next meeting. If the ROK forces should violate the armistice, they thought that the enemy was entitled to know where the UNC would stand. The policy makers in Washington, however, were still unwilling to be too specific. After consultation with Defense and State Department representatives, the JCS informed Clark that although he had the power to withdraw logistical support from the ROK forces, they preferred that a more general answer be offered to the enemy. They suggested the following response: "The UNC will not give support during any aggressive action of units of ROKA in violation of the armistice. In saying this we do not imply that we believe any such violation to be probable."5

At the 11 July meeting the Communists dismissed the UNC statements of the previous day as "full of contradictions" and "not satisfactory." Nam pressed again for definite "yes" or "no" answers to his queries without success. In responding, Harrison pointed out the measures adopted by a side to fulfil its armistice obligations were internal matters to be determined by that side alone. He did, however, inject into the record the general declaration proposed by the StateDefense group the day before. But the enemy delegates wanted more; they insisted that the commanders on each side should order and enforce the complete cessation of hostilities by all units under their control.6

The inability of the U.N. Command to relieve adequately the Communists' doubts about the future conduct of the ROK armed forces led Clark to cast about for another expedient. He found one in the Rhee letter of 9 July to Robertson wherein the ROK President stated that he would not obstruct the truce. But Robertson pointed out that he had agreed not to release this letter publicly pending further negotiations. On the other hand, Robertson saw no reason why Harrison could not tell the Communists that suitable assurances had been received from the ROK Government that it would work during the posthostilities period in close collaboration with the UNC for common objectives.7

On 12 July Harrison passed this information on to the Communist delegation and told them that the UNC, which included the ROK forces, was prepared to carry out the terms of the truce. After a recess, Nam commented that while the UNC statement was "very good" and "helpful," it still was not quite enough. The rest of the session witnessed a series of thrusts and parries, with the enemy pressing for definite pledges and the UNC shunting aside the demands and standing pat on the general assurances already given.8

To assess whether the Communists were genuinely worried about the ROK threats at this point or had simply decided to delay a settlement until the results of their July offensive were determined, would be difficult. Probably both factors entered into their calculations, since the disturbing press releases attributed to Rhee indicated that the old warrior viewed the truce merely as a temporary rather than a long-term halt in the fighting. This, of course, ran counter to the soothing statements made by the UNC at Panmunjom and might well have made the Communists suspicious. On the other hand, the July offensive had been planned for some time and it was unlikely that the enemy would have come to terms before its completion regardless of whether Rhee had been silent or even cooperative. At any rate, the Communists used the uncertainty over Rhee's actions as a convenient screen-real or fancied-for the deferment of final agreement.

After the 13 July meeting the enemy clearly was awaiting the outcome of its operations at the front. During this session Harrison gave some frank answers to the questions previously raised. He told the Communists that the U.N. Command would turn over the rest of the nonrepatriates to the Neutral Nations Repatriation Commission to quiet their anxiety lest the ROK Government seek to release additional prisoners in this category. The UNC was prepared to insure that the ROK forces observed the cease-fire and withdrew from the demilitarized zone. It would guarantee the safety of the personnel connected with the various commissions and of the Communists engaged in carrying out postarmistice duties in South Korea. If the ROK forces violated the truce and the Communists took counteraction, the UNC would continue to maintain the state of armistice and would give no support in equipment and supplies to the ROK units carrying out the aggressive operations.9 It was true that the UNC would not promise to use force to secure ROK obedience to the truce, but it must have been obvious to the enemy that no ROK offensive could have been successful for long without UNC assistance.

Nam, however, was not prepared to accept the UNC responses as yet. He reverted to the matter of the escaped nonrepatriates despite the fact that there was little hope of recovering them at that late date. Then he proceeded to press Harrison for a reconciliation between the ninety days, mentioned in Rhee's recent speeches as the length of time that he had agreed to for not obstructing a truce, and the armistice, which specified no such time limit. Harrison repeated several times that the UNC recognized that there was no time limit to the cease-fire and would act in conformity with this knowledge.10

When this meeting was over, Harrison urged that the U.N. Command recess the conferences, unilaterally if necessary, until the Communists realized that no more promises or pledges would be made. He regarded the enemy tactics of the succeeding days as plainly harassing while the Communists watched the progress of the actions on the central front.11

By 14 July Clark and his superiors had come to agree with Harrison and they gave him authority to walk out of the discussions the following day if the enemy persisted in pursuing its policy of procrastination. 12 The UNC delegation left the tent on 15 July after pointing out that the scale of the Communist offensive belied their sincerity in reaching agreement on an armistice. But before the UNC recessed the conference for a longer period, Clark suggested that Harrison give the enemy a more explicit answer on the ROK position as it had been developed in the RheeRobertson talks. Clark wished to inform the Communists that the ROK President had given the UNC "written assurances" that he would not obstruct the truce, but the political and military leaders in Washington modified the phrase to "necessary assurances."13

As it turned out, the change in wording made little difference. On 16 July the Communist delegation stole a march on the UNC and suggested a two-day recess in the negotiations.14 They later asked that it be extended to 19 July and the UNC agreed. In the meantime the enemy consolidated its gains along the front and halted the UNC counterattack in the ROK II Corps area.

Clark flew to Korea on 17 July and conferred with Harrison at Munsan-ni. They informed the JCS that they intended to reject further enemy demands for the return of the escaped prisoners and for firmer pledges on ROK future behavior. If the Communists requested a renegotiation of the demarcation line because of the current military operations, the U.N. Command would agree and then recess unilaterally for four days. The Washington leaders concurred in this course of action, provided that the Communists consented to naming a date on which the armistice would be signed and insisted upon renegotiation of the demarcation line.15

When the conferees returned to Panmunjom on 19 July, the enemy offensive was over and the battle line had been stabilized once again. The Communists were now ready to go ahead with the final arrangements for the cease-fire, Nam declared, although they were not yet completely satisfied with the UNC guarantees. They reserved the right to bring up the problem of the released prisoners at the postarmistice political conference. And since the ROK Government had refused to admit the Indian forces into their territory, Nam demanded that the truce conference settle the matter of handing over the remainder of the nonrepatriates to the repatriation commission now rather than committing the task to the Military Armistice Commission. As Clark and Harrison had anticipated, Nam also asked for renegotiation of the demarcation line. He evaded the efforts of Harrison to establish a target date for the signing of the truce.

The UNC senior delegate tried to discover when the Communists expected the Czech and Polish contingents for the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission to arrive, by announcing that the Swiss and Swedish advance components would be prepared to function shortly. If all went well, Harrison stated, the details could be concluded within five days and he urged that the effective date of the cease-fire be twelve hours after the signing. The supervisory commission should be ready to take over as soon as the armistice went into effect, he went on, and until that time each side should be responsible for the safety of the members it had nominated.

The Communists agreed that the plenary sessions should be suspended and that the staff officers should now begin. at once to settle all the points still in dispute. For the U.N. Command, Harrison informed Nam, Col. Douglas W. Cairns, USAF, would replace Colonel Darrow and join Colonel Murray on the staff group on the renegotiation of the demarcation line and revision of the armistice agreement. Col. Louis C. Friedersdorff, USA, would head the UNC officers discussing the repatriation of prisoners, and Col. John K. Weber, USA, would be in charge of the UNC staff group considering physical arrangements and rules of procedure pertaining to the functioning of the Military Armistice Commission.16

Late in the afternoon the plenary conference finished its penultimate session. After 158 meetings spread over more than two years, the original ten members of the delegations had dwindled to two- Nam II and his fellow countryman, Lee Sang Cho, who had helped to sustain the fiction that the Democratic People's Republic of Korea was directing the truce discussions for the Communist side. Despite the loss of continuity occasioned by the rotation of personnel, the major issues had finally been solved and the prospects for peace became brighter.

Now the task of reaching agreement on the minor problems descended upon the shoulders of the staff officers as it frequently had in the past. They would have to work their way through the maze of petty details that would determine when the fighting officially would come to a halt.

The Home Stretch

There were four areas in which the two sides still had to come to an agreement: the line of demarcation and demilitarized zone; the place of delivery of the nonrepatriate prisoners; the inception of activities by the various commissions established under the armistice; and the physical arrangements for the actual signing of the truce document. Negotiations on the staff level began almost immediately on these matters and continued, in at least one case, until the final day of the war.

On 20 July Colonel Murray and his opposite, Col. Huang Chen-chi of the Chinese Communist delegation, set to work on the revision of the demarcation line. In many places the job was relatively simple, since there had been little or no action in the locale and the line of contact was easy to determine.

In others, where recent fighting had shifted the front line, the problem became more complex. Here bargaining proved to be necessary, as each side sought to retain possession of as much favorable terrain as possible. Indeed, on occasion both sides claimed more than they had a right to, since it was apparent that the Communists and the U.N. Command could not both control a particular hill simultaneously. But, on the whole, the sessions were without rancor and even had their moments of humor. On 22 July Murray tried to end the haggling over several points in dispute along the line by making a package compromise offer. Colonel Huang, in typical fashion, accepted only the portion favorable to the Communists, leading Murray to comment: "In other words, in the interest of getting agreement, I offered you the shirt off my back. In place of accepting it gracefully, you returned to the conference table and asked for my drawers." Nevertheless, the horse trading continued until early the next morning, when all differences had been settled. Murray and Huang then initialed the copies of the maps to be printed and included with the armistice agreement.17

Before the staff officers took up the disposition of the nonrepatriates, Harrison and Clark decided that the expressed desire of the Communists to settle the place of delivery before the armistice went into effect should be exploited. To accomplish this, they instructed Murray to introduce an amendment to the draft agreement for consideration at the opening session on 22 July, proposing that the Communist prisoners who did not wish to return home should be turned over to the repatriation commission in the southern part of the demilitarized zone.18

Col. Ju Yon, senior staff officer for the Communists, accepted the suggestion in principle, but dismissed the idea that an amendment would be necessary. Instead he proposed that a temporary supplementary agreement be used covering the terms of admission for the nonrepatriates and the administrative personnel into the demilitarized zone. The Communist draft permitted each side to use its own half of the demilitarized zone for turning over nonrepatriates to the repatriation commission and for establishing the facilities required to handle the prisoners of war. Since the substance rather than the form of the understanding was the important thing, Clark and Harrison approved the enemy's alternative. The Communists, in turn, agreed that, to save time, the supplementary proposal should be typed up and signed separately instead of being printed and added to the text of the armistice agreement. By 25 July the staff officers had worked out the details and ordered the interpreters to go ahead with putting the terms into final shape.19

During the staff meetings the Communists had on several occasions evidenced great interest in learning the exact number of prisoners that were to be repatriated directly and of those that would be given over to the repatriation commission. The U.N. Command refused to supply other than round figures to the enemy, reasoning that there might well be some last-minute changes and that it would be simpler not to have to explain them to the Communists. Thus, leaving some margin for shifts in loyalty or homesickness, the UNC announced on 21 July that there would be 69,000 Koreans and 5,000 Chinese returning to Communist control. Three days later the UNC followed up with the release of the totals on the nonrepatriates-14,500 Chinese and 7,800 Koreans. In contrast, the Communists evidently had made up their minds on the exact figure they would deliver to the United Nations Command. The tally came to 12,764, including 3,313 U.S. and 8,186 Korean personnel.20 Since the enemy totals were not too far off from the numbers the UNC had estimated they could expect, Clark recommended they be accepted and his superiors agreed.21

The staff committee on repatriation of prisoners, headed by Colonels Friedersdorff and Lee Pyong Il of the North Korean Army, had the task of determining the rate of delivery for the repatriates. To a large degree the rate depended upon the transportation facilities and the administrative capacity of each side to handle the prisoners. At first, the UNC had calculated that it would be able to bring 1,800 repatriates a day to Panmunjom plus 360 sick and wounded. When Friedersdorff passed the information on to Lee, the latter immediately asked for 3,000 a day, in addition to the sick and wounded. As it was, the UNC would be transferring more than seven times as many prisoners over to the Communists each day than it received. For Lee disclosed that his side would turn over only 300 a day because of the paucity of transportation facilities and the fact that the Communist prisoner camps were distant and scattered. On 26 July a reassessment of UNC capabilities revealed that it could bring daily to Panmunjom 2,400, plus the 360 sick and wounded, but the enemy clung to its earlier figure.22 At that rate the U.N. Command would repatriate all of the prisoners in its custody desiring to return home in about thirty days, while the Communists would spread their deliveries over a forty-day period.

Meanwhile, over in the committee considering the preparations for the functioning of the Military Armistice Commission, Colonel Weber and his associates presented the UNC plans for the rules and modus operandi on 20 July.

Clark had already selected Maj. Gen. Blackshear M. Bryan, USA, Deputy Chief of Staff, FEC, as senior UNC member and established headquarters for the group at Munsan-ni on 20 June. During the succeeding month General Bryan had gathered his staff together and was ready to take up his duties as soon as the armistice went into effect.23

The Communists did not have any basic objections to the UNC recommendations, but showed no disposition toward haste. They agreed that the Military Armistice Commission should hold its first meeting on the day after the armistice was signed. Once the sessions got under way, they went on, the staff members could arrange the details of the operation.24

As one item after another was settled, the question of timing assumed greater importance. From the outset, the UNC staff officers had sought to have the armistice take effect twelve hours after the signing. The Communists, estimating that the personnel of the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission might not arrive in Korea and be able to exercise their functions for at least a week after the signing, had proposed that the effective date be seven and a half days later. In his rebuttal, Colonel Murray argued that even if the supervisory groups did not begin to carry out their responsibilities for a week, the agreement not to augment forces should. become effective twelve hours after the cease-fire. On 22 July the enemy representatives stated that although the UNC interpretation was at variance with the provisions of the armistice agreement in some respects, they were willing to accept it.25 Whether the Communists would scrupulously observe the restrictions imposed by the truce during the interim week was a matter for conjecture, but at least the casualty lists would not be increased by an extra seven days of fighting.

The first target date for the signing of the ceasefire had been 24 July, since five days had been adjudged sufficient to take care of the details and the physical arrangements. But complicating factors soon made this choice appear unduly optimistic-the demarcation maps had to be printed and checked after the line had been settled, the building for the signing ceremony had to be constructed and outfitted, and a difference in opinion had broken out over the signing procedure.

The debate over this formality produced the final enemy effort to eke out political advantage during the conflict. In the initial exchange on the ways and means that might be adopted, the Communists stated on 20 July that, in view of the uncertain ROK situation, they did not think it wise for the military commanders to attend and sign in person. Colonel Ju suggested that the commanders affix their signatures before the ceremony and then the senior delegates could countersign at Panmunjom.26

Clark looked with disfavor upon the enemy plan, for he strongly felt that the commanders should show their good faith by personally signing the armistice, thus lending prestige to the agreement. When Murray pressed the Communist representatives on 2l July to change their position, however, he met with little encouragement.27 Nevertheless he returned to the fray two days later and sought to assure the enemy that all possible precautions would be taken at Panmunjom to guarantee the safety of the commanders during the ceremonies. The U.N. Command, Murray said, would be willing to increase the number of guards, to limit and carefully screen all the representatives admitted to the conference area, and to provide immunity from attack for the Communist commanders en route to Panmunjom. But Colonel Ju pointed to the disconcerting statements that Rhee and other members of the ROK Government were still making as prejudicial to personal appearances by the commanders. To answer some of the UNC objections to the Communist proposal, Ju continued, his side was willing to have the senior delegates sign the armistice first and to have the truce go into effect twelve hours later. Thus any delay in securing the commanders' signatures would not hold up the actual cease-fire.28

At the liaison officers meeting on 24 July, Ju offered a third alternative. If no representatives of Syngman Rhee and Chiang Kai-shek were admitted to the conference area and if the number of personnel permitted to witness the signing were restricted to 100 for each side and included no press members, the Communists might reconsider and have their military commanders sign in person.29

Clark's initial reaction to the latest enemy suggestion was to accept even though he knew that the press would be very unhappy over being excluded from the signing room. General Taylor had conversed with Rhee and discovered that the ROK leader did not desire to send a representative to Panmunjom, so this potential obstacle was removed. But after further study of the enemy's demands, Clark changed his mind. He had no intention, he told the JCS, of banning ROK and Chinese Nationalist correspondents from the conference site area as the Communists insisted. If the enemy refused to allow the ROK and Nationalist newsmen to be present at the signing, he would settle for the senior delegates holding the ceremony first, with the commanders countersigning later.30

When the liaison officers convened their meeting on 25 July, Colonel Murray made several fervent pleas in behalf of the ROK and Nationalist press members, but they fell upon deaf ears. Ju would not consider their being in the area during the signing. If the UNC consented to their exclusion, Marshal Choe Yong Gun, Kim's deputy, and General Peng Tehhuai, Commander of the Chinese People's Volunteers, would come to Panmunjom on 27 July at 1000 to sign for the Communists, Ju declared. Otherwise, he went on, his side would not allow any press representatives to be present.31

The adamant stand by the enemy against ROK and Nationalist participation decided Clark. Early on 26 July he instructed Harrison to go ahead and sign at Panmunjom; lie would countersign afterwards at Munsan-ni since President Eisenhower wanted him to do this on Korean soil.32

At the liaison officers conference later that day, Murray and Ju completed the arrangements. Each side would be given 350 spaces in the Panmunjom area, but only 150 persons would be granted access to the signing building. Newsmen, photographers, and cameramen would be included in the 150 figure. The conference site would be divided into two sections and all personnel from one side should remain in its own half. Additional security guards would be on hand to preserve order and prevent disturbances. As previously suggested, the ceremony would be held at 1000 on 27 July.

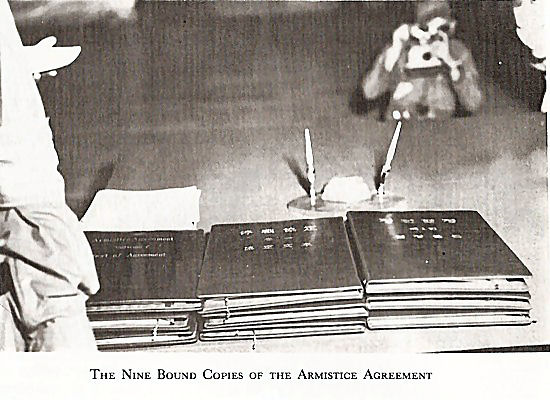

Murray and Ju encountered little difficulty in straightening out these matters. But an attempt by Murray to simplify the exchange of documents after they were signed by the commanders met with immediate suspicion and rejection by his opposite number. Since only 6 of the 18 copies of the truce were to remain in UNC possession, Murray suggested that the Communists take 6 copies to Kim and Peng while the UNC had the 12 copies intended for enemy possession countersigned by Clark. This procedure would necessitate only one exchange, Murray explained. Ju insisted upon absolute equality right to the end; each side would have 9 copies for countersignature despite the fact that two exchanges would be required under this method. In arguing for the Communist view, Ju discounted the time lost under his scheme as unimportant, causing Murray to retort: "Do I understand you correctly in that the strong point of your proposal is that it takes a long time to carry it out?" Ju ignored the thrust and early on 27 July Murray agreed to the Communists' proposal to end the matter.33

The Big Day

Although there were occasional puddles in lowlying spots and a heavy cloud cover, the sun managed to break through intermittently on 27 July. A strong wind whipped across Panmunjom stirring up little whirls of dust here and there. In the background the sound of artillery served as a reminder that the war was not quite over.

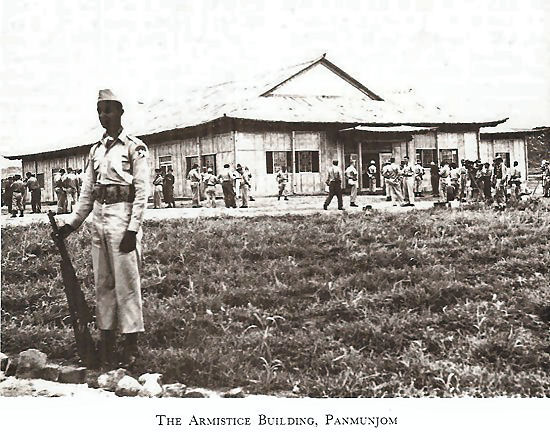

The building constructed for the ceremony had had a deletion and an addition in recent days. A UNC complaint had succeeded in securing the removal of two Communist peace doves from the gables of the peace pagoda and General Clark had insisted upon the provision of a south entrance to the structure. In the original plan the only door lay on the north side and this would have required all of the UNC entourage to pass through the enemy section to enter the building.34

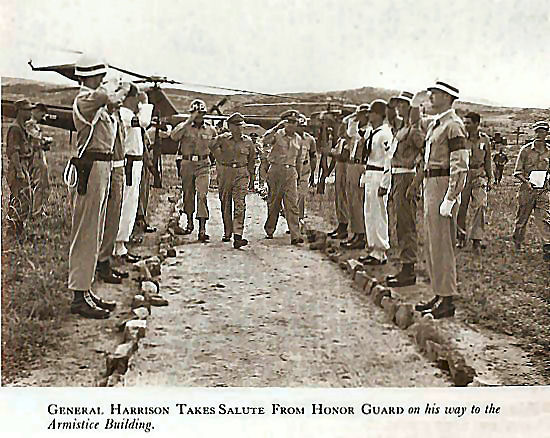

Along the south approach to the pagoda a UNC honor guard composed of members of the nations that had fought in Korea lined the walk, with only the Republic of Korea not represented. Smartly turned out in white gloves, scarves, and helmets, the guard added a dash of color to the scene. On the north side the Communists, clad in olivedrab fatigue uniforms and canvas shoes, were busily cleaning up the area near the entrance.

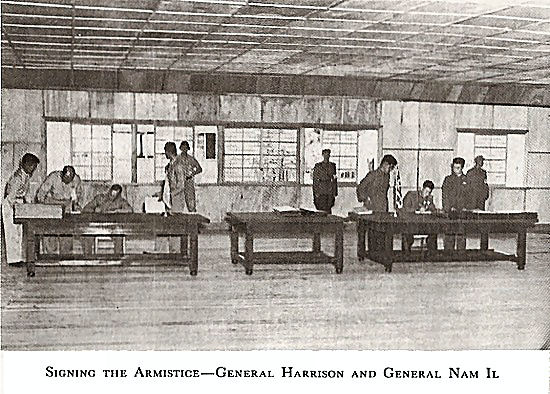

A half hour before the ceremony the spectators began to drift into sight. Correspondents and cameramen went into the building and took up their stations, followed soon after by the military officials from each side assigned to act as observers. In severe contrast to the casual, informal entrance and appearance of the UNC officers,, the Communists were stiff and disciplined as they filed into the hall and took their seats. Both Chinese and North Koreans "sat straight and rigid like students at a graduation ceremony, sized and posed."

Upon one of the tables at the head of the room lay nine blue-bound copies of the agreement and a small U.N. flag and upon another, nine marooncolored copies and a North Korean flag.

At 0957 the associate delegates of the plenary conference came in and sat down at the front. As the minute hand signaled the hour, Generals Harrison and Nam briskly walked in from opposite ends of the building and took their places behind the tables. Not a word of greeting was exchanged between the two men as they began to write their signatures on the documents. The atmosphere was marked by cold courtesy on both sides. At 1012 the task was completed and Harrison allowed himself a small smile at the cameras. As he and Nam rose to leave, they locked glances for a moment, but neither spoke. Harrison went out and chatted with the newsmen for a few minutes, then left for Munsan-ni by helicopter. Nam and his group climbed into their Russian-built jeeps and drove out of the area. The armistice but for twelve hours was finally a fact. (Map IX)

Postlude

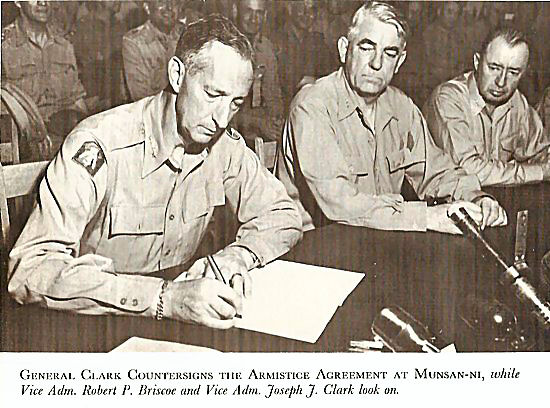

Surrounded by his top military advisors, including a ROKA representative, General Clark countersigned the bluebound copies on the afternoon of 27 July at Munsan-ni. In the speeches that followed, the U.N. commander cautioned that the armistice was only a military agreement to cease fire while the opposing sides sought a political solution to the conflict. Until the diplomats negotiated a permanent conclusion, Clark warned, there could be no UNC withdrawal from Korea nor any lessening of alertness and preparedness.35

While Clark was speaking, the guns along the front continued to bellow out their lethal salutes. Ground activity had come to a halt, but artillery and mortar fire lasted until the end. In the air the UNC planes pounded North Korean airfields, rail lines, and road systems in a last-ditch effort to curtail Communist activities until the supervisory commission and its inspection teams could begin to function. The air program, carried out by Air Force, Navy, and Marine aircraft, had been intensified during the last week of the fighting, but unfortunately, inclement flying weather had permitted the enemy to bring a number of airplanes into Korea before the armistice was signed.36 On the sea naval warships bombarded Kosong and finally ended the longest naval siege in history by shelling Wonsan for the last time.37 When the clock hands reached 2200 the guns fell silent across Korea and the shooting war was over.

How long the truce would last was uncertain. When Taylor had gone on the eve of the truce to inform Rhee that it would be signed on the morrow, the ROK President had seemed relieved that the long and trying struggle was almost over.38 During Clark's visit with Rhee on 27 July the latter had told the U.N. commander that he would tell his people that the ROK would cooperate with the armistice and that he would prepare a message to be read to the nonrepatriate prisoners to reassure them. In the course of their chat, Clark told the ROK President of an offer from Eisenhower to make 10,000 tons of food available immediately to the civilian population. The rations would be distributed through the Korean Civil Assistance Command in conjunction with the ROK authorities, if the latter were agreeable to the acceptance of the gift. Rhee seemed glad to receive the news and gave his consent, Clark reported.39

Despite these favorable signs, Rhee and his aides in their public utterances and interviews continued to indicate that the truce might not last long and that the ROK forces might again resort to arms if and when the political conference failed.40 It was impossible to estimate whether these threats might be serious or were simply delivered for home consumption to soften the blow of ROK acquiescence to the armistice. But they did inject into the situation a note of uneasiness that would have to be eliminated if the cease-fire were to be other than temporary. The United States could only hope that when fulfilled the pledges of military and economic assistance made to the ROK Government would overcome its objections to the truce and induce the ROK leaders to halt their agitation for a resumption of hostilities in the future.

The inability of the UNC participants to depend upon Rhee's behavior made them very hesitant about issuing the joint declaration, agreed upon earlier, providing for "greater sanctions" in the event the Communists began anew the fighting in Korea. As long as there was reasonable doubt about Rhee's intentions, the U.N. countries who had joined in the war preferred not to give broad publicity to their commitments under the agreement. Instead they decided to issue notice of the warning through a special report that the U.N. commander would submit to the United Nations on the armistice about a week after it was signed. Thus, in place of an independent statement which would have been given wide distribution, the following item was included in Clark's summary of the negotiations presented to the U.N. on 7 August:

We the United Nations members whose military forces are participating in the Korean action support the decision of the Commander-in-Chief of the United Nations Command to conclude an armistice agreement. We hereby affirm our determination fully and faithfully to carry out the terms of that armistice. We expect that the other parties to the agreement will likewise scrupulously observe its terms.

The task ahead is not an easy one. We will support the efforts of the United Nations to bring about an equitable settlement in Korea based on the principles which have long been established by the United Nations, and which call for a united, independent and democratic Korea. We will support the United Nations in its efforts to assist the people of Korea in repairing the ravages of war.

We declare again our faith in the principles and purposes of the United Nations, our consciousness of our continuing responsibilities in Korea, and our determination in good faith to seek a settlement of the Korean problem. We affirm, in the interests of world peace, that if there is a renewal of the armed attack, challenging again the principles of the United Nations, we should again be united and prompt to resist. The consequences of such a breach of the armistice would be so grave that, in all probability, it would not be possible to confine hostilities within the frontiers of Korea.

Finally, we are of the opinion that the armistice must not result in jeopardizing the restoration or the safeguarding of peace in any other part of Asia. 41

Regardless of the manner of presentation, the commitment was made and no less noted for having been slipped into Clark's report. Whether the Communists would heed the warning or not, only the future could reveal. It was possible that Syngman Rhee might take the decision out of their hands and place both sides in a quandary. In the meantime an armed truce during which the opponents could seek to improve their relative positions offered a modus vivendi less costly than open war.

The organizations which the U.N. Command and the Communists had designed to prevent one side from improving its military position significantly during the truce quickly assumed their duties and enjoyed some initial success. On 28 July the Military Armistice Commission held its first meeting and the proceedings were conducted in a businesslike manner. Arrangements were made in subsequent sessions for the withdrawal of troops from the demilitarized zone, the conduct of salvage operations, the removal of hazards such as mines, and the matter of credentials and identification of personnel entering or working in the zone. But the era of co-operation was soon shattered by a series of incidents in August which arose from the Communist Red Cross activities in the UNC prisoner of war camps. The atmosphere at the MAC meetings grew strained and charges and countercharges again became the order of the day. Each side denied the accusations of the other and the joint observer teams set up to investigate violations of the demilitarized zone usually had to submit split reports.42

Even more important were the experiences of the Neutral Nations Supervisory Commission and its inspection teams. The latter were stationed at the ten ports of entry specified in the truce agreement to observe and report on the arrival and departure of personnel and the replacement of combat materiel. In North Korea the inspection teams soon ran into difficulties, and the UNC charged that the enemy was violating the spirit and letter of the agreement by using other ports of entry to introduce more men and equipment. Little could be done to enforce the maintenance of the status

quo under the circumstances, the UNC concluded, and the Communists would continue to gain in strength as long as the UNC closely observed the provisions of the truce.43 Whether the apparent enemy build-up was offensive or defensive in nature or simply opportunistic, only time would reveal.

Another of the armistice's creationsthe Neutral Nations Repatriation Commission-also suffered its share of frustrations. Shortly after the truce was signed, the flow of prisoners north and south got under way. Between 5 August and 6 September the U.N. Command transferred over 75,000 prisoners of war directly to the Communists in the demilitarized zone and the enemy sent back over 12,000 to the UNC.44 Then, on 23 September, the United Nations Command turned over more than 22,000 nonrepatriates to the Neutral Nations Repatriation Commission in the demilitarized zone; the Communists delivered over 350 UNC nonrepatriates to the NNRC the following day.45

The Communists soon complained that the facilities provided them for persuading their nonrepatriates to return home were inadequate and it was not until 15 October that they began their explanations. Between this date and 23 December, when the ninety-day period agreed upon for explanations expired, they utilized only ten days for explanations. Large groups of the prisoners refused to listen to the enemy representatives at all and the number of those who chose repatriation after hearing the explanations amounted to only a little over 600 out of the 22,000 involved. The NNRC retained custody of the remainder until the 120 days stipulated in the truce agreement was up and then returned them to the UNC. In the early part of 1954 the Korean nonrepatriates were released and the Chinese were shipped by plane and boat to Taiwan, except for some 86 who chose to go with the Custodial Forces of India when they sailed for home.46

Of the 359 UNC nationals who had decided not to be repatriated, two of the Americans and eight Koreans changed their minds before the 120-day period was up and two Koreans elected to go to India with the custodial forces. The remainder were turned back to the Communists in January 1954.

When the American prisoners of war were interviewed after their repatriation, disturbing charges of collaboration and moral and physical softness were leveled at many of the returning soldiers. Criticism of the U.S. prisoner of war behavior became widespread in the press during the fall and winter of 1953-54. Over 500 of the repatriated prisoners were investigated, but only a few were convicted of misconduct. The Secretary of Defense did, however, appoint a ten-man Advisory Committee on Prisoners of War to investigate the matter. As a result the committee drafted a new code of conduct for the armed services, which President Eisenhower signed on 17 August 1955. It was hoped that the code would prevent a recurrence of the Korean experience.47

Since the war had never been declared, perhaps it was fitting that there should be no ending. In late August 1953 the U.N. General Assembly had welcomed the holding of a political conference which the truce agreement had recommended, but it was not until February 1954 that the Foreign Ministers of the United States, the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union, and France agreed to participate in a conference at Geneva to discuss the peaceful settlement of the Korean question.48

Delegations from the Republic of Korea and from all the nations participating in the United Nations Command except the Union of South Africa met with delegations from the USSR, Communist China, and North Korea on 26 April 1954 in Switzerland.49 The fundamental differences in the approaches of the two groups to the unification problem quickly demonstrated that agreement would be impossible unless one side made wholesale concessions. The UNC nations proposed free elections throughout Korea under U.N. auspices after the Chinese Communist forces had been withdrawn from the country. To the Communists, the U.N. was one of the belligerents and could not act as an impartial international body; they were willing to have free elections but only under the auspices of a body composed of equal representation from both sides wherein they would have veto privileges. To the UNC delegations the Communist proposals seemed to offer the prospects for elections only after long delays and on the Communists' terms. After nearly two months of discussions, the conference came to a close in mid-June with neither side willing to accept the other's solution. A negotiated unification of Korea appeared to be as distant in 1954 as it had been in 1948.

Notes

1 (1) Msg, CX 63548, CINCUNC to JCS, 8 Jul 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. 1-143, incl 12. (2) Msg, DA 943508, CSUSA to CINCFE, 8 Jul 53.

2 (1) Msg, CX 63567, CINCUNC to JCS, 9 Jul 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. I, 1-143, incl 12. (2) Msg, DA 943508, CSUSA to CINCFE, 9 Jul 53.

3 The composition of the delegations had not changed since the last meeting on 2o June, but two of the delegates were relatively new. Maj. Gen. Kim Dong Hak of the North Korean Army had replaced Rear Adm. Kim Won Mu on 17 June and Maj. Gen. George G. Finch, USAF, had replaced General Glenn. General Choi of the ROK Army did not attend the meetings after 16 May. General Finch had been a lawyer and had organized the first Air National Guard wing in 1946.

4 'Transcript of Proceedings, 151st Session, Mil Armistice Conf, 10 Jul 53, in FEC Min Delegates Mtgs, vol. VII.

5 (1) Msg, CX 66586, Clark to Collins, 10 Jul 56, DA-IN 285965. (2) Msg, JCS 946567, JCS to CINCUNC, 10 Jul 56.

6 Transcript of Proceedings, 152d Session, Mil Armistice Conf, 11 Jul 56, in FEC Main Delegates Mtgs, vol. VII.

7 (1) Msg, CX 66627, Clark to JCS, 11 Jul 56, DA-IN 286476, (2) Msg, CX 63635, CINCUNC to CINCUNC (Adv), 12 Jul 56, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 56, incls to app. I, incls 1-143, incl 29.

8 Transcript of Proceedings, 153d Session, Mil Armistice Conf, 12 Jul 53, in FEC Main Delegates Mtgs, vol. VII.

9 Transcript of Proceedings, 154th Session, Mil Armistice Conf, 13 Jul 53, in FEC Main Delegates Mtgs, vol. VII.

10 Ibid.

11 Msgs, HNC 1819 and 1821, CINCUNC (Adv) to CINCUNC, 13 and 14 Jul 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. I, incls 1143, incls 38 and 43.

12 Msg, JCS 943836, JCS to CINCFE, 14 Jul 53.

13 Msg, JCS 943913, JCS to CINCFE, 15 Jul 53.

14 Transcript of Proceedings, 157th Session, Mil Armistice Conf, 16 Jul 53, in FEC Main Delegates Mtgs, vol. VII.

15 (1) Msg, C 63749, CINCUNC to JCS, 17 Jul 53 in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. I, incls 144-286, incl 273. (2) Msg, JCS 944074, JCS to CINCFE, 17 Jul 53.

16 Transcript of Proceedings, 158th Session, Mil Armistice Conf, 19 Jul 53, in FEC Main Delegates Mtgs, vol. VII.

17 Transcripts of Proceedings, Eighth through Tenth Mtgs of Staff Officers To Renegotiate the Military Demarcation Line, 20-22 Jul 53, in G-3 File, Transcripts of Proceedings To Renegotiate the Military Demarcation Line . . . , Jun-Jul 53.

18 (1) Msg, HNC 1833, CINCUNC (Adv) to CINCUNC, 19 Jul 53. (2) Msg, C 63821, CINCUNC to CINCUNC (Adv), 19 Jul 53. Both in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. 1, incls 1-143, incls 70 and 71.

19 A copy of the supplementary agreement is reproduced in Appendix C. (1) Msg, C 63904, CINCUNC to CINCUNC (Adv), 23 Jul 53. (2) First through Fourth Mtgs of Combined Staff Officers, 22-25 Jul 53. All in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. I, incls 1-143, incls 88, 83, 89, 93, and 96.

20 Msg, CX 63970, CINCUNC to CG AFFE, 25 Jul 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. I, incls 144-286, incl 227. The remaining UNC personnel were broken down as follows: U.K., 922; Turkey, 228; Philippines, 40; Colombia, 22; Australia, 15; Canada, 14; France, 13; South Africa, 6; Belgium, 1; and Greece, 1. Three Japanese were also to be returned, according to the Communist tally, to total 12;764 in all. For the final figures on repatriation, see Appendix B.

21 (1) Msg, CX 63929, CINCUNC to JCS, 23 Jul 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. I, incls 1-143, incl 102. (2) Msg, JCS 944523 JCS to CINCUNC, 24 Jul 53.

22 Second and Fourth Meetings of Staff Officers on the Committee for Repatriation of Prisoners of War, 23 and 26 Jul 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. I, incls 1-143, incls 104 and 105.

23 UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, app. I, pp. 313-14.

24 First, Second, and Third Mtgs of Committee for Making Preliminary Arrangements for the MAC, 2o, 22, and 26 Jul 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. 1, incls 144-286, incls 252, 255, and 255.

25 (1) Liaison Officers Mtg, 21 Jul 53. (2) First Combined Mtg of Staff Officers, 22 Jul 53. Both in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. I, incls 1-143, incls 111 and 83.

26 Liaison Officers Mtg, 20 Jul 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. 1, incls 1-43, incl 74

27 Liaison Offcers Mtg, 21 Jul 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. I, incls 1-143, incl 111.

28 Liaison Officers Mtg, 23 Jul 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. I, incls 1-143, incl 119.

29 Liaison Officers Mtg, 24 Jul 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. I, incls 1-143, incl 112.

30 (1) Msg, CX 63963, CINCFE to JCS, 24 Jul 5g. (2) Msg, CX 63969, CINCFE to JCS, 25 Jul 53. Both in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. I, incls 1-143, 144-286, incls 121 and 277.

31 Liaison Officers Mtgs, 25 Jul 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. 1, incls 1-143, incls 122 and 97.

32 (1) Msg, DA 944648, CSUSA to CINCUNC, 25 Jul 53. (2) Msg, CX 64002, CINCUNC to CINCUNC (Adv), 26 Jul 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. I, incls 1-143, incl 126.

33 Liaison Officers Mtgs, 26 and 27 Jul 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. 1, incls 1-143, incls 127 and 136.

34 The description of the ceremony is based on UNC/FEC, Command Report, July 1953, Appendix I, pages 134ff.

35 (1) ZX 37264, CINCFE to CG AFFE et al., 26 Jul 53. (2) Msg, C 64152, CINCUNC to JCS, 31 Jul 53. Both in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. I, incls 144-286, incls 159 and 156.

36 Futrell, The United States Air Force in Korea, 1950-1953, pp. 639-40.

37 Hq UNC, Communique No. 1689, 28 Jul 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. I, incls 144-286, incl 158.

38 Msg, G 7445 KCG, Taylor to Clark, 27 Jul 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. I, incls 144-286, incl 206.

39 Msg, GX 7452, CINCUNC to JCS, 27 Jul 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. I, incls 144-286, incl 286.

40 Msg, GX 7608, Taylor to Weyland, 31 Jul 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. 1, incls 144-286, incl 209.

41 Unified Command's Special Report on Korean Armistice, in the Dept of State Bulletin, vol. XXIX, No. 739 (August 24, 1953) , p. 247.

42 UNC Summary of the Implementation of the Armistice Agreement in Korea, Part Two, no date. In OCMH.

43 Ibid.

44 See Appendix B for a breakdown of the statistics on prisoners of war.

45 The following account is based upon the Interim Report, 28 December 1953, and the Final Report, no date, of the Neutral Nations Repatriation Commission and the United Nations Command Report on Operations of the Neutral Nations Repatriation Commission, no date. All in OCMH.

46 See Appendix B.

47 New York Times, August 18, 1955. The justice and validity of the charges have been discussed in detail in postwar writings. For the arguments upholding the thesis that the prisoners did collaborate excessively with the enemy and demonstrated signs of moral and physical weakness, see Eugene Kinkead, In Every War But One (New York: W. W. Norton and Co., Inc., 1959) . For a convincing rebuttal of the thesis, see Albert D. Biderman, March To Calumny (New York: The Macmillan Co., 1962).

48 See Department of State. The Record on Korean Unification, 1943-1960 (Washington, 1960), p. 25. 49 For the record of the proceedings at the Geneva Conference see Department of State, The Korean Problem at the Geneva Conference, April 26-June 15, 1954 (Washington, 1954).

Causes of the Korean Tragedy ... Failure of Leadership, Intelligence and Preparation