History  On Line

On Line

"During the hectic final four months before the cease-fire in Korea," General Clark commented in his memoirs, "the U.N. Command was confronted almost literally with a crisis a day. Never, it seemed to me, was it more thoroughly demonstrated that winning a satisfactory peace, even a temporary one, is more difficult than winning a war."1

It was perhaps ironic that the majority of the problems to which the U.N. commander referred emanated from the actions of the ROK Government and its shrewd chief, Syngman Rhee, rather than from the machinations of the enemy. But such was the case. Although none of the political, economic, and military questions that were at the bottom of the ROK agitation were arising for the first time, there was a new sense of urgency on the scene. With the UNC and the Communists on the verge of composing their differences, the ROK Government felt it had to find the answers to the problems considered vital to the future of the nation before the war ended or its bargaining powers would be materially lessened.

Conceivably the UNC could sign a military armistice without the concurrence of the ROK, but how long would it last? If the Rhee Government decided to fight on alone or to create a succession of provocative or embarrassing incidents, a paper truce would be of little value. The United States had too much at stake in Korea to abandon its investment lightly. On the other hand, the Republic of Korea depended and would continue to depend heavily upon economic, financial, and military assistance from the United States for its existence as a nation. It was clear that each needed the other. The uncertainty centered on whether Rhee would come to terms or refuse to accept the conditions of the armistice. If he chose the former course the price for his acquiescence might come high in financial and economic aid. If he elected to carry on the war on his own, the cost in UNC casualties and prestige might be even less palatable. This was a turning point for the Republic of Korea; a wise or a hasty decision might make or break its future.

A Sense of Insecurity

The roots of ROK resistance to the armistice rested in a bed of insecurity and frustration. As the United States and its U.N. allies had shown less and less interest in the active prosecution of the war, President Rhee and his advisors had seen their hopes for a Korea unified by force become more and more unattainable. They had no way of knowing what role the United States would assume in Far East affairs during the years ahead; it was quite possible that the United States might again decide that Korea lay outside its area of strategic concern and abandon the ROK after the truce was arranged.2 Of course, there was still the political conference stipulated in the truce agreement, but, in the light of past experience with the Communists, few realists expected that such a meeting would produce results of any importance.

On the bright side, the ROK was receiving from the United States financial and economic help that enabled the country to fight the tide of inflation and to begin the task of reconstruction. The ROK Army was expanding and was better trained and equipped than it had ever been before. But the inescapable fact remained to plague the ROK leaders-all of this depended upon the United States and they had no guarantee of the future policy of the United States in the postwar period. During the spring of 1953, the ROK search for security formed the backdrop to the action taking place on stage.

There were evidences of ROK feelings of doubt and uncertainty even earlier. In February General Clark heard that the ROK Government wanted to move its seat back to the capital city of Seoul. During the two-and-a-half years of war the government had spent most of its time in Pusan. The instability of the battle situation had argued against the re-establishment of the administrative and legislative functions so close to the lines, and the U.N. Command had opposed placing such a tempting target within reach of a Communist offensive again. Besides, as Clark had pointed out in his request for U.S. support to block a move to Seoul, if the ROK Government returned, it would mean that thousands of people would flow into the capital and dozens of buildings would have to be rehabilitated.3

While Clark was protesting, the ROK Government asked the U.N. Command to transfer its headquarters from Tokyo to Seoul. Rhee also wanted the economic reconstruction organizations, such as UNKRA, to move to Seoul along with the UNC. In view of his mission as Far East commander, which precluded leaving Japan, and the lack of adequate housing and communications facilities in the South Korean capital, Clark rejected the suggestion. He felt that Rhee's dislike of Japan had inspired this recommendation.4

The U.S. political and military leaders supported Clark's stand against bringing the governmental machinery back to Seoul. In early March the U.N. commander was able to approach Rhee on the matter and secure his assurance that the chief ROK ministries would remain in Pusan.5 Yet the desire of Rhee and his followers to bolster the feeling of governmental stability by a return to Seoul and their jealousy of Japan's status reflected the tenor of the times.

On the economic front ROK newspaper stories in mid-January claimed that the prisoners of war were fed more adequately than the ROK Army security forces guarding them. As the accounts were picked up by the U.S. news services, President Eisenhower became concerned over the situation. He remembered that during World War II he had encountered a similar problem in Europe. The German prisoners, living off U.S. rations, had fared far better than the French and British soldiers who comprised the custodial troops. The President wanted to know what measures were being taken to remedy the discrepancies and whether U.S. surplus foods might help.6

Actually the ROK Government was responsible for the food consumed by its own troops, Clark commented, but frequently, because of poor distribution facilities and command failures, the ROK soldiers had not always received their quotas. The United States furnished only the materials for making biscuits and for canning purposes. He did not think that malnutrition was the primary cause of the poor physical condition of many ROKA troops, but rather it was secondary to the chronic diseases, such as tuberculosis, which had gone undetected during the initial physical examination of recruits. As spring approached, Clark noted, the availability of fresh produce would increase and the ROKA rations would improve. The Eighth Army, meanwhile, would study the matter and help set up a food supervisory service for the ROKA.7

Clark suspected the motivation behind the publicity accorded the ROKA and prisoner of war rations, for he surmised that the objective sought was more financial aid from the United States.8 At the end of March he received a confirmatory report from General Herren, the Korean Communications Zone commander. Although Herren felt that the ROK Government was seeking greater financial aid without accurately appraising its own assets or attempting to rectify its deficiencies, he estimated that the United States would have to provide more assistance in its drive to build up the armed forces and yet maintain reasonably stable economic conditions.9

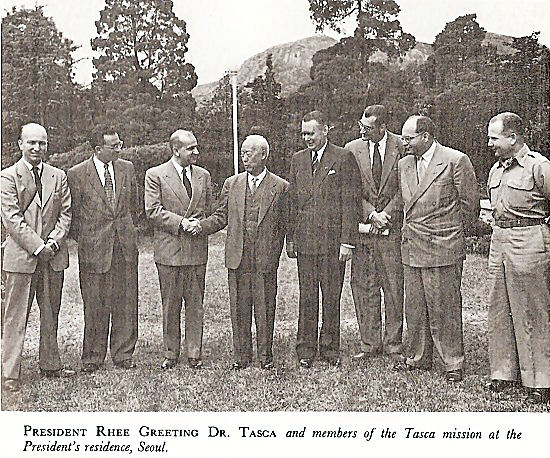

Early in April the President decided to get a firsthand report on the economic situation in South Korea. On 9 April he named Dr. Henry J. Tasca to carry out a full investigation of ways and means to strengthen the Korean economy and to make recommendations as to the amounts and types of assistance that should be provided by the United States.10 Dr. Tasca arrived in mid-April and spent the next seven weeks in surveying the scene. When he returned to the United States in June, he submitted a bulky and comprehensive report on existing conditions and suggested a number of remedial actions that could be taken. The initial recommendations called for the expenditure of a billion dollars over a period of three years and urged the reorganization of U.S. economic activities under a single head to promote more co-ordination and efficiency in the spending of funds.11 The Tasca mission offered evidence that the United States contemplated a long-term financial investment in the Republic of Korea and served to allay some of the ROK's fears about its economic future.

In the military field, meanwhile, the efficient mechanism established to produce recruits for the ROK Army continued to dominate the making of policy on ROKA expansion. Feeding some 7,200 inductees a week into the training units during a period of low casualties at the front inevitably led to a rapid increase in the over-all strength of the ROK Army. In early April Clark reported that the induction machine's pace would send the ROK Army beyond its authorized strength of 460,000 before the month ended.12 Since he was still reluctant to curb the flow of replacements, Clark suggested that he be granted authority to build up to a balanced, twenty-division force of approximately 655,000 men. At the present rate, this total would be reached around late August and would constitute the ultimate strength of the ROKA. He pointed out that if permission were given now, he could cut back promptly on the men assigned to training duties when the time arrived and could activate the additional divisions quickly as they were needed. As an extra inducement for approval of his request, the U.N. commander mentioned that when the seventeenth of the twenty ROKA divisions attained the halfway mark in training, he would be able to release the first U.S. division from Korea.13

Two days later, on 9 April, Clark asked for authorization to activate two new ROK divisions. He desired that the Department of the Army replenish theater stocks used to outfit the thirteenth and fourteenth ROK divisions and provide enough equipment to take care of the two new ones. Despite the possibility of a ceasefire, he urged the continuance of the twentydivision program. As he pointed out, if the war went on, the expanded ROK Army could either contribute toward the winning of a military victory or make possible the eventual withdrawal of U.N. forces and, if the fighting stopped, it could help to guarantee ROK independence. The Secretary of Defense granted Clark permission on 17 April to raise the total of activated ROK divisions to sixteen and G-3 informed him that an increase of 65,000 in the ROKA ceiling strength was under consideration.14

Behind the gradual, piecemeal approach to ROK Army augmentation adopted by the Eisenhower administration lay the hope that the promise of further expansion might reassure President Rhee. Clark was concerned lest the enemy seek to block the growth of ROK forces through stipulations written into the truce agreement and in May he again pressed for approval of the twenty-division program.15 General Collins supported Clark's request and on 14 May the President approved the twenty-division, 655,000-man ROK Army. Activation of the last four divisions was left to Clark's discretion, but Collins warned him that certain critical items of equipment such as artillery might not be available until later.16

In view of the increasing tension of the ROK situation in late May, Clark deferred action on the augmentation. When he finally decided to bring up the matter again in early June, the JCS informed Clark that if he decided to go ahead with the increase, then he should make it clear to Rhee that the expansion would be effected on the assumption the ROK would co-operate with the U.N. Command.17

As it turned out, the difficulties that the UNC continued to have with the ROK Government led to the deferment of the activation of the additional divisions until after the armistice was signed.18 The strengthening of the ROK Army, in this case, was delayed by the unwillingness of the ROK Government to accept the conditions attached. It was, of course, another effort by the United States to bolster the security of the Republic of Korea and to prepare the young nation for the task of eventually defending itself, but the build-up had to await a more opportune moment.

In the matter of Marine, Navy, and Air Forces, the ROK Government fared somewhat better. President Rhee had expressed a personal interest in the status of the augmentation of the ROK Marine Corps to Clark in late April and the U.N. commander in turn told the JCS that a favorable answer might be helpful in mitigating ROK discontent. In mid-May the Secretary of Defense informed Clark that an increase in the ROK Marine Corps to 23,500 had been approved by the President, along with new personnel ceilings of 10,000 for the ROK Navy and 9,000 for the ROK Air Force.19

But the planned growth of ROKA forces and the economic assistance that the United States hoped would provide a firmer base for the future security and development of the Republic of Korea were not enough. President Rhee and his advisors were deeply concerned over the present and with what they could salvage from the dying embers of a three-year war.

Friend or Foe?

During the long winter recess ROK opposition to the armistice had lain dormant. There seemed to be little purpose in beating a dead horse. But when the Communists indicated in late March that they would be willing to resume negotiations and to settle the prisoner of war question, the ROK Government quickly awoke to the implications of what this could mean to its national aspirations.

Within a week of the Communist offer Rhee and his staff had reopened their campaign to block a truce that did not meet their terms. The ROK National Assembly adopted a resolution in the opening days of April urging the United States to avoid any plan not guaranteeing the complete unification of Korea. On 5 April Rhee addressed the soldiers of the ROK II Corps on their first anniversary. He called for military victory and a drive to the Yalu rather than a truce along the present lines. In Seoul, on the next day, 50,000 people attended a rally that featured a succession of speakers denouncing the armistice and posing five demands as prerequisites to a settlement in Korea. First on the list came the matter of ROK representation in the United Nations; second, the total disarmament of North Korea; third, the removal of all Chinese forces from North Korea; fourth, ROK representation at all meetings discussing Korean problems; and last, cessation of support of North Korea by certain U.N. members.20

As the full weight of the ROK drive against the armistice began to make itself felt, Clark and his advisors started to worry. General Herren warned of stubborn resistance ahead which should not be discounted. When the U.N. commander communicated his anxiety to his superiors in Washington, they admitted their own concern over the situation.21

On 10 April 50,000 students paraded in Pusan displaying "Unification or Death" posters in great numbers as they wended their way through the city. The theme of national unification by force was repeated by public officials on every level. As General Herren pointed out to Clark on 14 April, the motivation behind the rising clamor linked the strong national desire for unification with the feeling of insecurity stemming from the 1950 aggression, with the reality of political pressure of the RussoChinese powermass, and with the fear that the United States would not again come to the ROK's aid in the event of future aggression. Herren was afraid that Rhee might do something rash to achieve his objectives, since the ROK President seemed to be in a position to channel "public opinion" in whatever direction he desired. To prevent hasty action by Rhee, Herren suggested that an approach be made along the lines of a bilateral security pact, which the ROK Government appeared to desire very much, coupled with postwar economic aid and the promise of U.S. support of Korean unification by peaceful means and of ROK participation in the political conference.22

Clark shared Herren's anxiety over the deterioration of the situation, but did not think that the United States should offer Rhee a bilateral security pact under pressure. One of the weaknesses of the UNC's position, he informed the JCS on 18 April, lay in the fact that under the present arrangements Rhee could make independent use of the ROK forces after the armistice was signed, since no agreement on UNC control in the posttruce period existed. He did not think, however, that it was the proper moment to raise this matter either.23

As it happened, Clark did not have to bring up the problem. On 21 April the ROK National Assembly passed resolutions in support of Rhee's position on the military unification of Korea by an advance to the north. Rhee followed this move by having Ambassador You deliver a message to the State Department three days later. The message informed Mr. Eisenhower that Rhee was preparing to withdraw ROK forces from the U.N. Command if the latter made any arrangement permitting the Chinese Communists to remain south of the Yalu. Under such circumstances, the ROK armed forces would fight onalone if necessary.24

The arrival of this brief document created consternation in Washington and Tokyo, for with the plenary sessions about to reconvene the threat of ROK non-co-operation loomed large. Since the timing of the withdrawal of ROK forces was the critical point, Clark told General Collins that he intended to see Rhee immediately and discover when the ROK President intended to pull out his troops from the UNC. If Rhee would wait until after the post-truce political conference was held, arrangements could be made to disengage other U.N. units and Clark could retain a large measure of control over the ROK forces by restricting their logistical support. On the other hand, if Rhee made his move as soon as the armistice was signed and initiated action against the enemy, the UNC would be caught in the middle.25

Word came quickly from Washington for Clark to delay his visit until Ambassador Briggs turned over a message from Eisenhower to the ROK President. In this missive, Mr. Eisenhower attempted to reassure Rhee. The United Nations he pointed out, had successfully repelled the Communist invasion and would continue to press for the peaceful unification of Korea. But it had not and would not commit itself to achieving this latter objective through war. The U.S. President urged Rhee not to attempt to block the armistice, for such a course could conceivably lead to the loss of all that the Republic of Korea had gained at such terrific cost.26

On 27 April, Clark flew to Seoul to talk to the ROK President. Rhee was "calm, dispassionate and unemotional," the U.N. commander reported, and expounded his views "in a friendly manner." But these views had not changed a whit. What Clark did discover during the course of the conversation was that Rhee was not thinking of taking the ROK forces away from UNC control except as a last resort. The ROK President told Clark that he would pull out his troops only after "thorough and frank discussions" with the U.N. commander. After talking privately for over an hour with Rhee, Clark felt that the old man was bluffing and would not go it alone without giving the matter long and careful consideration.27

One of the topics that Rhee had stressed in the dialog with the U.N. commander was the feasibility of the simultaneous withdrawal of both Chinese Communist and U.N. forces. By 30 April the ROK leader had thought over this question and decided that only if certain safeguards were applied could the U.N. troops be removed. The conditions laid down by Rhee included in part: a bilateral defense pact; U.S. guarantees of immediate help in the event of Soviet aggression; the continuance of the naval blockade and air defense until peace was firmly established; and the expansion and strengthening of ROK armed forces in the meantime.28

Behind the adamant front presented publicly by the ROK President on unification and the ousting of the Chinese Communists, therefore, lay a disposition to bargain. He wanted the U.N. Command to remain to bolster the ROK position even though this was clearly inconsistent with his stand on the Chinese forces. But, unfortunately, his speeches and press releases were leaving him very little room to maneuver without making important concessions. The parades and demonstrations went on unabated even while he cautioned his people against improper acts that might be interpreted abroad as malicious in their intentions.29

During the early part of May another facet of the problem of relations with the ROK Government came into sharper focus. Rhee and his counselors had stated on several occasions that they would never permit the Korean nonrepatriates to be transferred to a neutral state.30 When the Communists dropped their demand on 7 May that the nonrepatriates be physically moved out of the country, the ROK Government entered a new spate of objections. Both the Communist and UNC plans for disposing of the nonrepatriates were predicated upon the stationing of custodial personnel and troops upon ROK soil. General Choi, the ROK delegate, quickly introduced a counterproposal amending the UNC plan. Provided that Switzerland was selected to serve as chairman of the repatriation commission and furnished all of the custodial forces, which would be concentrated on the island of Cheju-do, more than 50 miles south of the mainland, the ROK Government would be willing to agree to a neutral nation taking over control of the nonrepatriates in Korea.31

On 12 May Clark again visited Rhee to discuss the ROK attitude toward the repatriation Commission and found him "in dead earnest" about not turning over Korean nonrepatriates to any state or group of states having Communist inclinations. During this meeting Rhee asked Clark about the possibility of his having the ROK security troops guarding the Korean nonrepatriates release them without involving the U.N. commander. Clark reminded Rhee that the ROK security forces were under the UNC and the ROK President did not pursue the subject. In this matter Clark admitted his sympathy with Rhee's desire and urged the JCS to insist upon the release of the Korean nonrepatriates as soon as the armistice was signed.32 As has been mentioned above, the Washington policy makers allowed Clark's stand on the release as an initial position only and later gave way to the Communists' objections. But it was a clear indication of the seriousness of the situation in ROK eyes and foreshadowed later developments.

Since he had received no encouragement in his efforts to gain unification by force, to secure the eviction of the Chinese Communists, or to arrange for the release of the Korean nonrepatriates, Rhee cast his line into other waters. After the 12 May talk with Rhee, the U.N. commander relayed his impressions of the course that the ROK leader was following: "I feel Rhee realizes that, in spite of some of his heated objections, we will go ahead and obtain an armistice if we can get one that does not sacrifice the principle of no forced repatriation. He is bargaining now to get a security pact, to obtain more economic aid, and to make his people feel he is to have a voice in the armistice negotiations." Clark saw no reason why a mutual security arrangement could not be worked out as quickly as possible to satisfy this ROK goal. And he had suggested to Rhee that the staff of General Choi, the ROK representative at Panmunjom, be increased by several administrative officers to magnify the role of the ROK in the negotiations. Rhee had agreed and on 20 May three assistants of general officer rank joined Choi in the conference area.33

Although the threat of ROK action to prolong the war by fighting on alone diminished in early May, the Eighth Army staff dusted off the plans prepared during the ROK domestic crisis of a year earlier for safeguarding UNC forces and supplies in the event of internal disturbances. The situation had altered a great deal, of course, for now the chief concern lay in the observance of the armistice once it was signed. Much would depend upon the response of the ROK Army and populace to an actual appeal from Rhee to continue the conflict, and plans were hinged to the various degrees of co-operation that might be given to Rhee by his people. The task of disengaging UNC forces from the battle line during active hostilities between the ROKA and the Communists would present the most acute problem if it arose, and instructions were issued to the major commanders involved to cover such an eventuality.34

The possibility that the U.N. Command and the ROK Government would be able to reconcile their differences without serious incident lessened after the middle of May. When the Communists rejected the 13 May UNC proposal at Panmunjom, policy makers in Washington began to prepare the final UNC position. The abandonment of the stand on the release of the Korean nonrepatriates and the acceptance of India as chairman and supplier of custodial forces would be extremely difficult for the Republic of Korea to accept in the light of the strong declarations by Rhee and his fellow-leaders condemning such concessions. As the UNC gravitated closer to the Communist views on the outstanding issues, it drifted as a matter of course farther away from ROK desires.

Since the United States realized that the final UNC position would be distasteful to Rhee, officials in Washington fashioned a statement in the form of a personal message from President Eisenhower designed to reassure the ROK Government that the United States would not desert it in the days ahead. Clark and Briggs were instructed to deliver and discuss this with Rhee on 25 May. Perhaps the most important item at the moment was the bilateral security treaty, but because of ROK agitation against the armistice, the United States was not ready to negotiate a pact. The disinclination of the Washington policy makers to conclude a mutual security arrangement puzzled Clark, for he believed that Rhee attached great importance to this matter. Without a security agreement they would have little to offer Rhee that would serve to soften the impact of the concessions that the United States was about to make.35

Nevertheless, while the UNC delegation was presenting the new offer at Panmunjom on 25 May, Clark and Briggs met with Rhee and informed him of the terms that were being proffered to the Communists. They then informed Rhee in effect that the United States would support the Republic of Korea militarily, economically, and politically provided Rhee accepted and co-operated in carrying out the conditions agreed upon in the armistice. To bolster the prospects of peace after a truce, a "greater sanctions" statement by the U.N. countries participating in the Korean War would be issued immediately following the conclusion of the cease-fire. A bilateral security pact, however, could not be considered at the present, for it would weaken the U.N. aspects of the Korean efforts and might be hard to justify to the U.S. Congress under current circumstances.

The aftermath of this interview was hardly surprising. Since Rhee had not been consulted on the formulation of the final position and was kept in the dark on the extent of UNC concessions, Clark and Briggs were merely apprising him of the fait accompli. At the same time, to make matters worse, they had to tell him that he was not going to get a security treaty now and if he did not behave he might also not get all the assistance that had been promised him. According to the two U.S. representatives the armistice proposals came as "a profound shock" to Rhee. He immediately declared them unacceptable to his country and said therefore he could give none of the assurances of cooperation which the United States desired. Rhee did, however, ask that the points covered by Clark and Briggs be submitted in writing.

What Rhee would do to retrieve the situation remained unknown, but Clark warned his superiors shortly after the 25 May meeting of one dangerous possibility: . . . he may either covertly or overtly initiate action to cause the release of all Korean nonrepatriates. He has the capability, and should he attempt this action, there are few effective steps that I can take to counter it. Accordingly, I am bringing this matter to your attention, for such an eventuality would be most damaging to the UNC cause. It would be practically impossible to avoid charges of UNC duplicity, not only from the Communists but from our allies as well.36

It was true, Clark continued, that he could replace the ROK security battalions with U.S. troops, but this might aggravate an already delicate state of affairs and might also result in placing the U.S. forces in a position of having to employ force against the nonrepatriates if they attempted to escape. Since the only motive of these Koreans was to resist return to Communist control, it would be "particularly unfortunate" if U.S. personnel had to use violent means to avert a breakout. He had discussed the problem with his subordinate commanders and all were alerted to the potential explosiveness of the prisoner of war situation. They would take what preventive measures they could under the circumstances, but these might well be inadequate.37

During the interim between the presentation of the 25 May proposal to the Communists and the next meeting of the plenary conference, the tempo of ROK denunciations of the UNC offer increased. On 27 May the major points of the plan found their way into the ROK newspapers, apparently leaked by governmental sources. The ROK National Assembly listened on the next day to Foreign Minister Pyun Yung Tai attack the concessions granted and then lined up solidly in support of President Rhee. From General Choi, the ROK representative at Panmunjom, came a blast at the provisions for turning over the nonrepatriates to the repatriation commission, for holding the prisoners until either the political conference or the U.N. General Assembly could dispose of them, and for permitting Communists to enter ROK territory.38

When Choi's statements were given to the press, thus violating the executive nature of the plenary meetings, Harrison remonstrated with him in vain. After Choi declared that he would not attend further executive meetings and refused to promise compliance with the security rules, Harrison had little choice but to halt the flow of classified information to the ROK representative and his staff.39

As emotions began to run high, especially in ROK official circles, and warnings of trouble streamed in from U.S. military and diplomatic sources, the leaders in Washington wondered whether they might not have been too hasty in denying Rhee a mutual defense pact. On 29 May, Secretary of State Dulles and Secretary of Defense Wilson agreed that Clark could offer Rhee a bilateral security treaty if the U.N. commander thought that this might stave off a dangerous situation. Mr. Eisenhower approved on the following day.40

The belated decision had only one drawbackthere was no guarantee that Rhee would accept the bargain now. Neither Clark nor Briggs were sure of the reception that Rhee might give the tardy offer, but both felt that it should be held in abeyance until the Communists responded to the UNC 25 May proposal and Rhee had an opportunity to react to the Communists' reaction.41

Before the Communists could enter the picture again, however, Rhee sent an answer to the President's message of 25 May. Surprisingly enough, this letter was mild in tone and omitted all reference to the controversial matters of the Korean nonrepatriates and the repatriation commission. Instead the ROK leader concentrated upon what he considered the four major conditions that would make an armistice acceptable to the ROK people. First, the United States would conclude a mutual defense pact with the Republic of Korea and, second, would pledge military and economic support to strengthen ROK defenses. Third, the U.N. and Chinese Communist forces would withdraw simultaneously from Korea and, fourth, U.S. air and naval forces outside Korea would remain in the area to act as a deterrent to further aggression. As Clark pointed out to the JCS on 2 June, the U.N. Command could satisfy all of these conditions except for the question of withdrawal of all non-Korean forces. This would have to be taken up at the political conference unless the Communists would agree to include it in the armistice. Clark did not think that they would, but admitted that Rhee's answer was encouraging and showed no disposition toward undertaking rash acts. Nevertheless, Clark and Briggs still wanted to wait until after the next plenary session before they talked to Rhee again.42

Approval for deferring the visit arrived from Washington the following day. Collins informed Clark that he and Briggs could use their own discretion on whether to bring up the matter of the pact.43 In the opening days of June everything hinged upon the Communist acceptance or rejection of the UNC proposal. Despite the fact that both Rhee and the UNC expected the enemy to agree to the 25 May offer, they preferred to wait and make sure before taking the next step.

During this brief interlude there was one development that was quite significant in the light of later events - Rhee appointed Lt. Gen. Won Yong Duk, a trusted henchman, to the command of the Provost Marshal General's office. This command was directly under the Minister of National Defense rather than under the ROKA Chief of Staff and placed all military police at Rhee's disposition.44

When the Communists signified on 4 June that they would go along with most of the UNC suggestions, the ROK antiarmistice machine gathered fresh momentum. But it was operating now on two levels. On the level below Rhee, speeches, parades, and demonstrations continued to be inflammatory in tone, while the ROK President himself proceeded at a more cautious pace. At the meeting with Clark and Briggs on 5 June, Rhee attacked the armistice as appeasement, a Communist victory, and as the first step toward World War III. On the other hand, he hedged on ROK future action and refused to commit himself on whether a mutual defense treaty would counterbalance his objections to the truce. Clark and Briggs decided not to make the definite offer of a pact until a more favorable moment arose.45

Rhee issued a public statement on 6 June that was very similar in content to the letter he had sent Clark on 30 April. He proposed a simultaneous withdrawal of all non-Korean forces from the peninsula after a mutual defense treaty between the United States and the Republic of Korea had been concluded. The pact would guarantee U.S. military assistance, support in the event of aggression, and the retention of U.S. air and naval forces in the Far East area. If such an arrangement were not possible, then the ROK troops would fight on.46 It was Rhee's wish that the UNC delegation introduce the matter of non-Korean troop withdrawal at Panmumjom, but there was little chance that his desire would be gratified at a time when the UNC and Communists were so close to finishing up the truce arrangements.

Shortly after Rhee released this statement, President Eisenhower decided to try again. In his letter, delivered on 7 June by Clark, Eisenhower defended the negotiating of the armistice and then went on to again pledge U.S. supportpolitical, military, and economic-in the posttruce period. The message seemed to have little effect upon Rhee. Clark, reporting on his meeting with the ROK President, noted: "I have never seen him more distracted, wrought up and emotional." During the interview Rhee indicated that he and his people would never accept the armistice and that from now on he would feel free to take whatever steps were necessary. He refused to elaborate on what he would do or when he would act, causing Clark to conclude: "He himself is the only one who knows how far he will go, but undoubtedly he will bluff right up to the last."47

The first measures adopted by Rhee came on 7 June when "pseudo-extraordinary" security restrictions were imposed on all of South Korea and all ROK officers on duty in the United States were ordered home. By the time the terms of reference on prisoners were signed on 8 June at Panmunjom, the ROK campaign was in full swing.48 There were three principal themes stressed in the speeches, slogans, and placards: the unification of Korea; the release of the anti-Communist prisoners of war; and the use of military force to prevent the entry of the "so-called" neutral nations forces that were to take over custody of the prisoners.

In the midst of the wave of increasing internal excitement, General Taylor called on Rhee and introduced an alleviating factor into the situation. After a diatribe against the armistice Rhee reiterated his intention of continuing the struggle alone. Taylor proceeded to point out that the ROK Army still suffered from many deficiencies and needed time to convert itself into a balanced force capable of defending South Korea. Evidently the thought that the truce and the political conference would provide time to allow completion of the twenty-division program had not occurred to Rhee. In a more temperate tone, he told Taylor that he needed assurances to convince the Korean people of the palatability of the armistice. These would include:

1. the limiting of the political discussion, preferably to sixty days;

2. a mutual security treaty with the United States;

3. the expansion of the ROKA to twenty divisions and the development of the ROK Navy and Air Force;

4. the barring of Indian and Communist representatives from Korean soil.

However, Rhee went on, he was not yet ready to take a final stand on this matter and wanted to think it over a bit more. Taylor received the impression that the ROK President was out on a limb because of the extreme position he had assumed on the withdrawal of foreign troops and was casting desperately for a means to save face while extricating himself.49

The uncertainty reflected in Rhee's conversation with Taylor was mirrored in the domestic events of the second week in June. Demonstrations in Seoul led to the injury of some high school girls and unfavorable publicity for the U.S. Military Police, even though they were not responsible for the cuts and bruises suffered. Yet, at the same time, many Koreans were weary of war and realized the futility of fighting on alone.50

On 12 June Secretary of State Dulles sent a letter to President Rhee suggesting that the latter come to Washington for high-level talks with the President and himself. Although the offer reportedly pleased Rhee, he turned it down because of the press of affairs. Apparently the ROK President was not yet ready to come to terms; instead he asked Dulles to visit him in Korea, where he would have the psychological advantage. This time Dulles had to decline. As an alternative he proposed sending Assistant Secretary of State Walter S. Robertson, who had the full trust of Eisenhower and Dulles, in his place. On 17 June Rhee told Briggs that he would be delighted to see Robertson when he arrived.51

On the same day, 17 June, Rhee called Briggs back and gave him his answer to Eisenhower's letter of 6 June. While expressing appreciation at the U.S. offers of assistance and a mutual security pact, Rhee did not feel that these could be accepted if they entailed ROK consent to the armistice.52 Later in the day he addressed a group of U.S. and ROK officers at ROK II Corps headquarters and became quite emotional in his speech denouncing the armistice and repeating the ROK intention to carry on the fighting by itself.53

The vague threats and hints of ROK action to block the truce cropped up again in Rhee's talk to the ROK officers, but the U.S. officials could do little to forestall a hostile or embarrassing act without aggravating the situation. By the same token Rhee faced a similar dilemma, for he was personally friendly to the United States and appreciated the help it had given South Korea. Yet his implacable opposition to the armistice could not be suddenly altered without loss of face in his own land. And any daring move that might save his face was bound to produce strained relations between his country and the United States. Rhee's choice was a difficult one, but it had to be made.

The Pacification of Rhee

On 18 June Rhee revealed his decision and confirmed the worst expectations of General Clark. The UNC press release issued was brief and succinct:

Between midnight and dawn today, approximately 25,000 militantly anti-communist North Korean prisoners of war broke out of the United Nations Command prisoner of war camps at Pusan, Masan, Nonsan, and Sang Mu Dai, Korea.

Statements attributed to high officials of the Republic of Korea now make it clear that the action had been secretly planned and carefully co-ordinated at top levels in the Korean Government and that outside assistance was furnished the POW's in their mass breakout. ROKA Security units assigned as guards at the POW camps did little to prevent the breakouts and there is every evidence of actual collusion between the ROK guards and the prisoners....

U.S. personnel at these non-repatriate camps, limited in each case to the camp commander and a few administrative personnel, exerted every effort to prevent today's mass breakouts, but in the face of collusion between the ROKA guards and the prisoners, their efforts were largely unavailing. The large quantities of non-toxic irritants employed proved ineffective because of the great number of prisoners involved in the nighttime breakouts. Nine prisoners were killed and 16 injured by rifle fire. There were no casualties among U.S. personnel.

As of 1 o'clock this afternoon 971 escaped POW's had been recovered.

ROKA Security Guard units which have left their posts at non-repatriate camps are being replaced by U.S. troops.54

Despite the celerity with which the U.S. security units took over their duties at the prison camps, they were forced to operate at a distinct disadvantage. In the event of mass escapes the custodial troops were authorized to use riot control measures but not gunfire. The United States was especially reluctant to use force against the anti-Communist prisoners and thus could only employ nontoxic gases and other nonlethal methods of control. Although the bulk of the prisoners gained their freedom on 18 June, mass attempts continued and hundreds more broke out in spite of the presence of U.S. guards. On 17 June there had been around 35,400 Korean nonrepatriates in the compounds; by the end of the month, only 8,600 remained. The price of liberty had become more costly, however, for 61 prisoners had died and 116 had been injured in the escape attempts.55

The uproar caused by Rhee's unilateral action did not center on whether the freeing of the prisoners was justified or not; it concerned itself rather with the effects of the ROK coup upon the negotiations. Although Clark had known that Rhee was in a position to release the nonrepatriates at any time, he told the ROK President that he was "profoundly shocked" at the abrogation of the personal commitment that Rhee had previously given him not to take unilateral action involving ROK troops under UNC control without informing Clark. A message from President Eisenhower echoed Clark's charge and intimated that unless Rhee quickly agreed to accept the authority of the U.N. Command to conclude the armistice, other arrangements would be made.56

Actually the accusation by Clark was not entirely pertinent. The promise made by Rhee had applied to the withdrawal of ROK forces from UNC control. After Rhee had appointed General Won as Provost Marshal, he had placed the security troops at the prison camps under him. Won, in turn, was responsible to the ROK Minister of National Defense and Rhee rather than to the ROKA Chief of Staff and the UNC. As for giving Clark prior warning of the plan to free the prisoners, Rhee pointed out: "Under the circumstances, if I had revealed to you in advance my idea of setting them free, it would have embarrassed you. Furthermore, the plan would have been completely spoiled."57

Although the ROK Government wanted to let all of the Korean nonrepatriates go, Rhee made no effort to use force. Neither he nor the U.S. officials wished to have armed clashes between the ROK and UNC troops. In response to Clark's request that Rhee promise not to free the Chinese nonrepatriates and any of the Communist prisoners, the ROK President agreed not to take any action along this line.58

The uncertainty over Rhee's next move and the delicate situation in the nonrepatriate prison camps made the latter part of June a very unsettled period. The escaped prisoners, for the most part, were integrated with the local population and were nearly impossible to recapture because of the assistance furnished them by the ROK authorities. In the newspapers, stories of UNC collusion on the prisoner escapes appeared and Clark had to issue a strong statement on 21 June denying that he had known about or abetted the release of the nonrepatriates.59

To forestall similar charges from the Communists, Harrison had informed Nam Il immediately on 18 June of the breakouts and placed the responsibility squarely on the shoulders of the ROK Government. But the enemy refused to believe that the U.N. Command had not known about the plan in advance and had not "deliberately connived" with Rhee to carry it out. Despite this, the Communists did not threaten to break off negotiations as they might well have done. Instead they posed several pertinent questions that struck at the heart of the matter. Is the United Nations Command able to control the South Korean government and army? If not, does the armistice in Korea include the Rhee group? If the Rhee group is not included, what assurance is there for the implementation of the armistice agreement on the part of South Korea?60 The Communists had a right to know the answers to these queries, but the UNC was in no position to provide them. Only Rhee could supply this information and he seemed disinclined to be helpful.

At a meeting with Taylor on 20 June the ROK President appeared surprised that the Eighth Army commander had not gotten an official reaction to the four points he had made on 9 June.61 He had evidently forgotten that he had not been ready at that time to present them as an official position. During this conference he gave notice that the signing of an armistice would automatically free him for further unilateral action, though he refused to commit himself on what this action might be.62 The mixture of threat, on the one hand, with interest in further horse trading, on the other, indicated that he had not closed the door to bargaining.

When Clark visited Rhee two days later, he found him nervous and tense, but very friendly. Both Clark and Taylor, when they compared impressions, felt that the adverse comments of the world press on Rhee's unilateral release of the prisoners was making an impact on him. The U.N. commander got straight to the point and told the ROK leader that he must accept the premises that the United States was determined to sign an armistice under honorable terms and would not try to eject the Communist troops from Korea by force. Moving on to the four points of g June, Clark said he thought that there should be a time limit on the political conference; that the United States could sign a security treaty, but would never agree to come to the aid of the ROK if the latter were the aggressor; and that the ROK forces would be built up. As for the last point, Clark aired his purely personal view that some modification in the prisoner of war agreement might be worked out. The 8,600 Korean nonrepatriates might remain in U.N. custody and the ROK representatives might be given full opportunity to explain the terms of reference to them. When the time came to turn these prisoners over to the repatriation commission they could be moved to the demilitarized zone and ROK representatives might sit in as observers while the Communists explainers carried on their sessions. The Chinese non-Communist prisoners could be turned over to the custody of a neutral state for final disposition. Such an arrangement, Clark told Rhee, would eliminate the need for Indian or Communist personnel to enter ROK rear areas.

Turning to another subject, Clark gave his frank opinion on the status of the ROK Army. It could not fight on its own, offensively or defensively, at the present and needed time to prepare for the assumption of larger tasks.

Throughout the discussion Rhee had listened intently, Clark noted, and he had appeared to be interested in the tentative solution that the U.N. commander had proposed. Although Rhee would not commit himself, Clark felt that he made one very significant remark. Despite the fact that he could not sign an armistice, since this would be an admission of the division of Korea, the ROK leader had indicated that he could support it. Clark requested quick guidance as to whether the United States desired him to continue further along the avenue he had suggested to Rhee.63

Before an answer could arrive from Washington, Clark forwarded an amendment to one of his proposals: instead of turning over the Chinese nonrepatriates to a neutral country, he advocated transporting them to the demilitarized zone in the same fashion as the Korean nonrepatriates and delivering all of the prisoners who were unwilling to return home to the repatriation commission.64

By this time the President and his advisors had decided to send Assistant Secretary of State Robertson and Army Chief of Staff General Collins to Korea. Clark had been told to discuss the matter of armistice modifications with the emissaries upon their arrival. The conference in Tokyo between U.S. military and diplomatic leaders in the Far East and Robertson and Collins took place on 24 June. All agreed that the armistice should be signed as quickly as possible. Clark and Murphy felt that the enemy would accept an armistice even though the UNC could not specifically guarantee that Rhee would live up to all of its provisions.65

At a meeting held in Washington the same day the report of this conference arrived, Mr. Eisenhower told his counselors that since Clark was on the spot and in the best position to assess the situation, he should be given wide authority to go ahead and conclude the armistice. In the instructions sent to Clark on 25 June he was told that as long as he did not compromise the principle of no forced repatriation and did not imply that the UNC would force the Republic of Korea to accept the armistice terms, he could handle the rest of the arrangements on his own. There should be no UNC commitment to withdraw from Korea, the Washington leaders stated, but if Clark thought it would be helpful, he could let the ROK leaders think that the UNC intended to pull out.66

After the demonstrations and speeches attendant upon the celebration of the third anniversary of the war's outbreak were over, Robertson conferred with Rhee on an almost daily basis. His chief mission was to clear up the misunderstandings that threatened to disrupt U.S.-ROK unity and to reassure President Rhee of U.S. friendship and concern for the future of the Republic of Korea. He immediately encountered the deep fear of the ROK Government that the United Nations might be weary of the war and might be ready to sacrifice Korea. As Robertson later reported, the bitterness found in the United States and among its allies over the release of the prisoners was duplicated in South Korea by a bitterness "distilled of their fears."67

Although at the meeting of 27 June Rhee admitted that President Eisenhower had met all of the conditions he had laid down and requested that they be given to him in writing, agreement was fleeting. Rhee added new conditions and modified his assurances.68

While the private conferences between Rhee and Robertson continued, Clark acted on the permission he had received to go ahead with the effort to wind up the armistice agreement. In his letter of 29 June to Kim and Peng, Clark attempted to answer the questions asked by the Communists. He pointed out that the UNC did command the ROK Army, but did not exercise control over the Republic of Korea, which was a sovereign nation. As to whether the armistice included the government of Rhee, he reminded his opposites that the armistice was a military agreement between the military commanders. Since the co-operation of the ROK Government was necessary in this case, however, the UNC and the U.N. governments concerned would make every effort to obtain ROK co-operation and would also set up military safeguards insofar as possible to insure observance of the terms. Clark suggested that the delegations meet immediately and discuss the final arrangements.69

Both Clark and Harrison became impatient as the diplomatic talks dragged on into early July. They felt that it was time to stop letting the ROK Government call the turn. General Clark believed that Mr. Eisenhower had made maximum concessions to Rhee and that it was time to let him know that there would be no more. In accord with the permission he had gained on 25 June to give the impression that the UNC intended to withdraw from Korea, Clark told the Secretary of Defense on 5 July, he had been pursuing a campaign of counterpressure upon the ROK. He had held conferences with his senior commanders, carried out some troop movements, consolidated the camps of the Korean nonrepatriates, slowed down the movement of supplies and equipment to Korea, and suspended the shipment of equipment for the activation of the last four ROKA divisions. In the future, he intended to curtail projects employing indigenous labor and reduce the use of Korean hwan. Military and naval activity would be aimed at fostering the belief that the UNC was preparing to pull out of Korea. As the indications that the UNC was leaving mounted, Clark thought that they would have a considerable impact upon Rhee and his advisors.70

On the same day-5 July-one of the facets of Clark's campaign produced encouraging results. In an interview with the press, General Taylor remarked that he could extricate the U.N. forces from the battle line amicably if the ROK Government decided to continue the fighting after the armistice. He went on to note, however, that the Eighth Army was like a twenty-cylinder automobile with a complex system of wires and cogwheels. If the U.N. forces were taken away, the ROK troops that remained would have to fashion a completely new automobile, Taylor concluded.71 The implication was clear that the ROK Army would face a major problem of reorganization in the event it fought on alone.

The evident U.S. determination to go on with the armistice negotiations was matched by Robertson's patience and tact with Rhee behind the scenes. As President Eisenhower has noted: "Day by day he argued with this fiercely patriotic but recalcitrant old man on the futility of trying to go it alone. He gave assurance of United States support if Rhee would be reasonable."72 To satisfy Rhee's fears that a postarmistice political conference might be carried on indefinitely to breed uncertainty and to serve as a cover for infiltration of hostile propaganda in South Korea, Robertson agreed that if it turned out that way, the United States would try to end the conference "as a sham and a hostile trick."73

While Robertson worked to allay the ROK President's doubts, the Communist liaison officers on 8 July delivered the long-awaited answer to Clark's request for the resumption of negotiations. Kim and Peng were still highly suspicious of the role the UNC had played in the escape of the prisoners of war and bitterly critical of the actions of Rhee and his government. Despite their detailed reservations about accepting the UNC explanations, the key sentence came in the last paragraph: "To sum up, although our side is not entirely satisfied with the reply of your side, yet in view of the indication of the desire of your side to strive for an early Armistice and in view of the assurances given by your side, our side agrees that the delegations of both sides meet at an appointed time to discuss the question of implementation of the Armistice agreement and the serious preparation prior to the signing of the Armistice agreement."74 Although this was a long-winded way of saying "yes," the fact that the Communists were willing to proceed in spite of the uncertain status of the ROK situation demonstrated how much they wanted an armistice.

The enemy's agreement to return to Panmunjom and the UNC counterpressure campaign evidently combined to have an effect upon Rhee. During the next three days Robertson was able to wind up his conversations with President Rhee. When Robertson left Korea on 12 July he had a letter signed by Rhee expressing his appreciation of Robertson's performance and "his fine spirit of consideration and understanding." Rhee also assured President Eisenhower that "he would not obstruct in any way the implementation of the terms of the armistice" despite "his misgivings over the long-term results."75

In return for this promise Rhee obtained five main pledges from the United States:

1. the promise of a U.S.ROK mutual security pact after the armistice;

2. assurance that the ROK would receive long-term economic aid and a first installment of two hundred million dollars;

3. agreement that the United States and the Republic of Korea would withdraw from the political conference after ninety days if nothing substantial was achieved;

4. agreement to carry out the planned expansion of the ROK Army; and

5. agreement to hold high-level U.S.-ROK conferences on joint objectives before the political conferences were held.76 |  |

These were important concessions, to be sure, but in the process of negotiation Rhee had dropped many of his previous demands. Through his agreement not to obstruct the armistice, he abandoned his insistence upon the withdrawal of Chinese Communist Forces from Korea and for the unification of Korea before the signing of the armistice. He also gave up his objections to the transportation of Korean nonrepatriates and Chinese prisoners to the demilitarized zone for the period of explanations, provided that no Indian troops were landed in Korea.

This was not the end of the Rhee story. During the closing days of the truce negotiations his presence was felt even as it had been before, but to a lesser degree. The reservations he had attached to his promises not to impede the armistice allowed him some room to maneuver and he caused the United States and its allies several anxious moments up to the end. But the period of his dominance of the negotiation was over when he agreed in writing to go along in general with the conclusion of the truce terms.

What the old warrior had accomplished by his fight was difficult to assess immediately. He had not succeeded in gaining United States support for his drive to unify Korea by military force nor had he carried the day for his plan to have the Chinese Communists withdraw from Korea before the armistice was signed. On the other hand, he had won the pledge of a bilateral security pact with the United States coupled with economic and military assistance; he had freed thousands of Korean nonrepatriates from the prison camps; and he had blocked the entry of Indian and Communist personnel into South Korea. Because of the delicate situation vis-avis the Communists at Panmunjom, the United States had been forced to cater to Rhee's desires in several instances to prevent further incidents and Rhee had gained face among his own people on these occasions. He had also shown the world that the Republic of Korea was not a puppet state. At the same time his tactics in blocking the arrangement of a cease-fire in Korea could not help but cause him to suffer a loss of friends and confidence among the other nations around the globe who desired an end to the fighting and the casualties. The use of speeches and mass information media such as the radio and press to fan public emotion and the organization and encouragement of demonstrations and parades to make clear ROK opposition to the armistice were quite effective, but in the long run may have cost Rhee more than they gained. The United States was willing to meet all reasonable demands to compensate the ROK for its acceptance of the truce; the campaign of open pressure merely made it more difficult for the United States to yield gracefully. In retrospect, it appeared that through diplomatic bargaining Rhee could have had all that he eventually won and could have avoided giving the Communists a chance to gloat over the falling out of allies. No one could belie his devotion to the national objectives of his country or his sincerity in pursuing them, but his tactics and judgment in attaining these goals were certainly open to question.

Notes

1 Clark, From the Danube to the Yalu, p. 257.

2 In January 1950 Secretary of State Acheson had declared that the United States would fight to defend Japan, Okinawa, and the Philippines, omitting both Korea and Taiwan as strategic objectives of vital concern to the United States. Department of State Bulletin, Vol XXII, No. 551 (January 23, 1 950), pp. 111 ff.

3 Msg, CX 61134 and CX 61225, CINCUNC to DA, 4 and 14 Feb 53. Both in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Feb 53, incls 1-88, incls 57 and 58.

4 Msg, C 61247, CINCUNC to DA, 16 Feb 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Feb 53, incls 1-88, incl 45.

5 (1) Msg, JCS 932503, JCS to CINCFE, 27 Feb 53. (2) Msg, C 61511, CINCUNC to JCS, 13 Mar 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Mar 53, incls 1-72, incl 47.

6 (1) Msg, CX 61237, CINCUNC to CSUSA, 15 Feb 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Feb 53, incls 1-88, incl 40. (2) Msg, DA 932033, Secy Army Stevens to Clark, 22 Feb 53. 7 Msg, C 61376, CINCFE to DA, 2 Mar 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Mar 53, incls 1-72, incl 39.

8 (1) Msg, CX 61237, CINCUNC to CSUSA, 15 Feb 53. (2) Msg, CX 61259, CINCFE to DA, 17 Feb 53. Both in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Feb 53, incls 1-88, incls 40 and 41. (3) Clark, From the Danube to the Yalu, pp. 182-84.

9 Msg, AX 73191, CG KCOMZ to CINCUNC, 28 Mar 53, UNC/FEC, in Comd Rpts, Mar 53, incls 1-72, incl 41.

10 UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 53, pp. 46-47. Dr. Tasca had formerly served as Treasury Attach? in Italy and more lately as deputy for economic matters to the Special U.S. Representative in Europe, William H. Draper, Jr.

11 Discussion of the Tasca mission and its report will be found in the UNC/FEC Command Reports of June and July 1953. Study and revision of the report was still going on when the armistice was concluded.

12 The ROKA had 438,000 men at this time, plus 75,000 trainees and 16,000 KATUSA, for a total of over 529,000 men.

13 Msg, CX 61791, CINCFE to Secy Army, 7 Apr 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 53, incls 1-110, incl 38.

14 (1) Msg, CX 61837, CINCFE to DA, 9 Apr 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 53, incls 1-110, incl 39. (2) MSG, DA 936843, G-3 to CINCFE, 17 Apr 53.

15 Msg, CX 62372, Clark to Collins, 12 May 53, DA-IN 266645.

16 Msg, DA 938886, CSUSA to CINCFE, 14 May 53.

17 (1) Msg, CX 62955, CINCFE to DA, 10 Jun 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jun 53, an. 3, sec II, tab J-66. (2) Msg, JCS 941344, JCS to CINCFE, 12 Jun 53.

18 UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, pp. 90-93.

19 (1) Msg, C 62181, Clark to JCS, 30 Apr 53, DA-IN 262924. (2) Msg, JCS 938796, JCS to CINCFE, 14 May 53. The 10,000 for the ROK Navy was 6,000 less than Clark had requested.

20 (1) Msg, G 3731, Taylor to Clark, 5 Apr 53. (2) Msg, G 3756, Eighth Army to AFFE, 6 Apr 53. Both in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 53, incls 1-256 to app. I, incls 222 and 223.

21 (1) Clark, From the Danube to the Yalu, p. 261. (2) Msg, C 61736, CINCFE to DA, 4 Apr 53, UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 53, incls 1-256 to app. I, incls 218 and 216. (3) Msg, JCS 936213, JCS to CINCUNC, 10 Apr 53.

22 Msg, C 61949, CINCFE to DA, 16 Apr 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 53, incls 1-256 to app. I, incl 230.

23 Msg, CX 61976, Clark to JCS, 18 Apr 53, DA-IN 258833.

24 (1) Clark, From the Danube to the Yalu, p. 261. (2) Msg, G 4404 KGI, Eighth Army to AFFE, 26 Apr 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 53, incls 1-256 to app. I, incl 237.

25 Msg, C 62098, Clark to Collins, 26 Apr 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 53, incls 1-256 to app. I, incl 250.

26 Ltr, Eisenhower to Rhee, 23 Apr 53. From p. 182 of THE WHITE HOUSE YEARS: MANDATE FOR CHANGE, 1953-1956, by Dwight D. Eisenhower. Copyright ? 1963 by Dwight D. Eisenhower. Reprinted by permission of Doubleday & Company, Inc.

27 (1) Msg, C 62143, Clark to Collins, 28 Apr 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 53, incls 1-256 to app. I, incl 255. (2) Clark, From the Danube to the Yalu, pp. 261-62.

28 Ltr, Rhee to Clark, 3o Apr 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 53, incls i-256 to app. I, incl 253.

29 (1) Clark, From the Danube to the Yalu, p. 263. (2) Msg, AX 73675, KCOMZ to CINCFE, 27 Apr 53, UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 53, incls 1 256 to app. 1, incls 247 and 245.

30 (1) Msg, AX 73525, KCOMZ to CINCFE, 16 Apr 53. (2) Msg, C 62143, Clark to Collins, 28 Apr 53. Both in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 53, incls 1-256 to app. I, incls 103 and 255.

31 Msg, HNC 1680, CINCUNC (Adv) to CINCUNC, 12 May 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, May 53, incls 1-194 to app. I.

32 Msg, HNC 1678, Clark to DA (JCS), 12 May 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, May 53, incls 1-194 to app. I. For Clark's account of the meeting and his views on the release of the nonrepatriates see Clark, From the Danube to the Yalu, pp. 262-65.

33 (1) Msg, CX 624o6, CINCFE to JCS, 13 May 53. (2) Msg, G 5100 KCG, Taylor to CINCFE, 19 May 53. Both in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, May 53, incls 1-194 to app. I.

34 (1) Eighth Army, Plan EVERREADY, 4 May 53, in G-3 381 Pacific, 15/3. (2) Memo, Brig Gen James A. Elmore, Chief Opn Div, for Gen Eddleman, 4 May 53, sub: CINCUNC Plans . . . , in G-3 091 Korea, 34/3.

35 Hq UNC/FEC Korean Armistice Negotiations (May 52-Jul 53), vol. 4, pp. 129ff.

36 Clark, From the Danube to the Yalu, pages 268-71, contains a detailed account of this meeting. See also, Msg, C 6263o, Clark to JCS, 26 May 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, May 53, incls 1-194 to app. I.

37 (1) Msg, 250610, Clark to JCS, 25 May 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, May 53, incls 1-194 to app. I. (2) Clark, From the Danube to the Yalu, pp. 272-74.

38 Msg, HNC 1706, CINCUNC (Adv) to CINCUNC, 29 May 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, May 53, incls 1-194 to app. I.

39 Msg, HNC 1711, CINCUNC (Adv) to CINCUNC, 1 Jun 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, May 53, incls 1-194 to app. I.

40 Memo for Rcd (sgd Eddleman), 1 Jun 53, sub: Conf on the Current Difficulties with the ROK Govt . . , in G-3 091 Korea, 46.

41 (1) Msg, CX 5478 KCG, Eighth Army to CINCUNC, 30 May 53. (2) Msg, CX 62747, CINCFE to JCS, 30 May 53. Both in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, May 53, incls 1-194 to app. I.

42 (1) Eisenhower, Mandate for Change, 1953-1956, p. 183. (2) Msg, Eighth Army to CINCUNC, 2 Jun 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jun 53, Source Papers 1-150, Paper 149. (3) Msg, CX 62781, Clark to JCS, 2 Jun 53, DA-IN 273323.

43 Msg, DA 940543, CSUSA to Clark, 3 Jun 53.

44 UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jun 53, p. 46.

45 Clark, From the Danube to the Yalu, pp. 27476.

46 Msg, CX 62854, CINCUNC to JCS, 6 Jun 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jun 53, Source Papers, 151-297, Paper 157.

47 (1) "Public Papers of the Presidents," Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1953 (Washington, 1960), pp. 377-80. (2) Msg, CX 62876, CINCUNC to Eighth Army, 7 Jun 53. (3) Msg, CX 62890, CINCUNC to JCS, 7 Jun 58. Both in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jun 53, Source Papers, 151-297, Papers 163 and 166.

48 Robert C. Allen, Korea's Syngman Rhee (Rutland, Vermont, Charles E. Tuttle Co., Inc., 1960), p. 160.

49 Msg, G 5812 KCG, Taylor to Clark, 9 Jun 53, in Hq Eighth Army, Gen Admin Files, Jan-Jun 53.

50 Msg, A 6661, FEAF to CINCFE, 16 Jun 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jun 53, Source Papers 151-297, Paper 178.

51 (1) Eisenhower, Mandate for Change, 1953-1956 p. 184. (2) Clark, From the Danube to the Yalu, p. 279.

52 (1) Eisenhower, Mandate for Change, 1953-1956, p. 185. (2) Hq UNC/FEC, Korean Armistice Negotiations (May 52-Jul 53) , vol. 4, pp. 223-25.

53 Msg, G 6092 KCG, Taylor to Clark, 17 Jun 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jun 53, Source Papers, 151-299, Paper 199.

54 Msg, ZX 36907, CINCFE to DA, 18 Jun 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jun 53, Source Papers, 151-297, Paper 217. The number of prisoners still at large on 18 June was 25,131.

55 UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jun 53, p. 46.

56 (1) Ltr, Clark to Rhee, 18 Jun 53, quoted in Hq UNC/FEC, Korean Armistice Negotiations (May 52-Jul 53), vol. 4, pp. 239-40. (2) Msg. CX 63164, CINCFE to CG Eighth Army, 19 Jun 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jun 53, Source Papers, 151-297, Paper 221. (3) Eisenhower, Mandate for Change, 1953-1956, pp. 185-86.

57 Ltr, Rhee to Clark, 18 Jun 53, quoted in full in Hq UNC/FEC, Korean Armistice Negotiations (May 52-Jul 53), vol. 4, pp. 246-47.

58 Msg, CX 63216, CINCUNC to Taylor, 20 Jun 53. (2) Msg, CX 63230, CINCUNC to DA, 20 Jun 53. Both in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jun 53, Source Papers, 151-297, Papers 227 and 233.

59 (1) Msg, DA 941831, Parks to Clark, 19 Jun 53. (2) Msg, C 63212, CINCFE to CINFO, 20 Jun 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jun 53, Source Papers, 151-297, Paper 237. (3) Msg, C 63242, Clark to JCS, 21 Jun 53, in same place, Paper 240.

60 (1) Ltr, Harrison to Nam, 18 Jun 53, in G-3 file, Liaison Officers' Mtgs at Pan Mun Jom, Jan 53-Jun 53, bk. III. (2) Ltr, Kim and Peng to Clark, 19 Jun 53, in FEC Main Delegates' Mtgs, vol. 7.

61 These had included a time limit on the political conference, a mutual security pact, expansion of the ROK armed forces, and the barring from Korea of Indian and Communist representatives. 62 Msg, GX 6228 KCG, Taylor to Clark, 20 Jun 53, in Hq Eighth Army, Gen Admin Files, Jan-Jun 53.

63 (1) Clark, From the Danube to the Yalu, pp. 282-84. (2) Msg, Clark to JCS, 22 Jun 53, DA-IN 280121.

64 Msg, Clark to JCS, 23 Jun 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jun 53, Source Papers, 151-297, paper 250.

65 (1) Msg, DA 942047, CSUSA to CINCUNC, 22 Jun 53. (2) Clark, From the Danube to the Yalu, pp. 284-85.

66 (1) Msg, JCS 942368, JCS to CINCFE, 25 Jun 53. (2) Clark, From the Danube to the Yalu, p. 289.

67 Radio Address of Dulles and Robertson, July 17, 1953, reported in Congressional Record, July 18, 1953, vol 99, pt. 7, p. 9128.

68 Clark, From the Danube to the Yalu, pp. 286-87.

69 Msg, HNC 1796, CINCUNC (Adv) to JCS, 29 Jun 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jun 58, Source Papers, 151-297, Paper 264.

70 (1) Msg, HNC 1800, CINCUNC (Adv) to CINCUNC, 4 Jul 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. I, 1-143, incl 2. (2) Msg, CX 63500, CINCUNC to Secy Defense, 5 Jul 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. I, incls 144-286, incl 176.

71 (1) Msg, CX 63524, CINCFE to DA, 7 Jul 53, in UNC/FEC Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. I, incls 144-286, Incl 178. (2) New York Times, July 6, 1953, p. 3.

72 Eisenhower, Mandate for Change, 1953-1956, p. 187.

73 Radio Address of Dulles and Robertson of July 17, 1958, reported in Congressional Record, July 18, 1953, vol 99, pt. 7, p. 9128.

74 Msg, HNU 7-1, CINCUNC (Adv) to CINCUNC, 8 Jul 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 53, incls to app. I, incls 1-143, incl 7.

75 Eisenhower, Mandate for Change, 1953-1956, p. 187.

76 Clark, From the Danube to the Yalu, pp. 287-88.

Causes of the Korean Tragedy ... Failure of Leadership, Intelligence and Preparation