History  On Line

On Line

When General Harrison and his associates walked out of the tent at Panmunjom on 8 October, they neither knew when they would return nor if they would come back at all. The possibility that the Communists would alter their attitude toward repatriation appeared extremely unlikely at that time and the military pressure that the U.N. Command could hope to muster gave no promise of producing a change in the enemy's stand. Since the UNC had fallen back upon its final negotiating position, the discussion phase and the period of maneuvering were at an end. Until a break occurred in the adamant fronts presented by both sides, the prospects for a settlement remained remote.

The liaison officers meanwhile continued to meet at Panmunjom and furnished one point of contact for reflecting a shift in the situation. The activity on the battlefield, especially during the October-November operations, provided another. And in the air over North Korea, the Far East Air Forces did its best to help speed up the enemy's desire to reach an agreement. To counter the application of military pressure, the Communists reverted to their old standbys-political and psychological warfare. But the efficacy of either the UNC or the enemy method was doubtful, since both had been tried before and found wanting.

The Long Recess: First Phase

The first nonmilitary attack by the Communists in October was aimed at the UNC tactics at Panmunjom. As soon as the Harrison team left the tent, the enemy began to charge that the UNC had broken off the negotiations. Since the onus for ,a collapse in the talks had always been a sensitive point to the political and military leaders in Washington, they quickly instructed Clark not to use the term "indefinite recess" in the UNC statements. They informed him that there was no desire to have the armistice negotiations debated in any forum other than that of Panmunjom and that all the efforts of the United States in the U.N. General Assembly were directed towards facilitating an agreement at the meetings in the tents.1

As the letters flew back and forth between the liaison officers in October, the courses adopted by the opponents became clear. The UNC stand rested upon the conclusion that the Communists had neither accepted any of the plans offered by the U.N. Command nor proffered any of their own that were new or reasonable; therefore, the UNC delegation would wait until the enemy satisfied one of the two conditions listed above before it would reconvene. Harrison and Clark denied repeatedly that the UNC had ended the negotiations.2

The Communists, on the other hand, pursued two tactics. While they pressed their accusations that the UNC had ended the truce talks, they missed no opportunity to cite UNC violations, real and alleged, of the neutral zone around Panmunjom. And as the incidence of violence in the prisoner of war camps started to increase again, the enemy negotiators strongly censured the UNC for its treatment of the Communist prisoners.3

To lessen the impact of the enemy's charges and to explain the UNC position in the negotiations to the rest of the world, Secretary of State Acheson addressed the U.N. Political Committee on 24 October. Tracing the beginnings of the talks and the development of the issues, he admitted that the growth of the conflict over repatriation had been "wholly unexpected" and "surprising" to the U.N. Command.' He pointed out the inconsistencies of the position adopted by the USSR in opposing the concept of no forced repatriation in Korea when it had on various occasions previously upheld the right of the prisoner of war to choose or refuse repatriation. In closing he stressed that the UNC was ready to reconvene the meetings at Panmunjom at any time that the Communists were willing to accept the "fundamental principle of nonforcible return." 6

While the debates in the General Assembly over the U.S. resolution against forcible repatriation were going on, other suggestions and resolutions were brought forth. One of these was an informal Canadian proposal that the UNC seek a cease-fire in Korea and leave the nonrepatriate problem to later negotiations. Both Army and State Department staffs objected to this procedure. To remove the threat of military compulsion would amount to a surrender of the UNC's most potent weapon, they maintained, while, at the same time, the Communists would keep their trump card-the UNC prisoners. The enemy could protract the discussions on the disposition of prisoners and in the meantime rebuild its airfields, roads, bridges and restock its supply dumps. If the talks proved fruitless and hostilities again broke out, the Communist military position could be greatly improved and UNC morale would be sadly depressed.6

Several weeks later when the joint Chiefs forwarded their views on the matter to the Secretary of Defense, they endorsed the ArmyState staff arguments. There could be no justification for giving up the UNC air superiority in Korea, they told Mr. Lovett, unless the Communists accepted the concept of no forced repatriation.7

On 17 November the Indian delegation presented its plan to end the Korean War to the United Nations. The Indian resolution recognized the U.S. contention that no force should be used to prevent or effect the return of prisoners to their homeland. Yet in deference to the Communist stand, it suggested that a repatriation commission, composed of two Communist and two UNC nations, be set up to receive all the prisoners in the demilitarized zone. There they would be classified according to nationality and domicile, as the Communists had wished, and be free to go home. Each side would have the freedom of explaining to the prisoners their rights, and all prisoners who still had not chosen repatriation after ninety days would be referred to the political conference recommended in the armistice agreement. In case the four members of the repatriation commission could not agree on the interpretation of the details of handling the prisoners and their disposition, an umpire would be named by the members or the General Assembly to break any deadlock.8

Although many of the United States allies favored the Indian proposal, at least in principle, the U.S. official reaction was quick and adverse. Most of the objections voiced by the United States concerned the vagueness of the duties and responsibilities that the repatriation commission would carry out and the indefinite procedure for handling nonrepatriates. Not only was the time limit of ninety days too long for the interrogation period, but the U.S. still opposed turning over the nonrepatriates to a political conference.9

But the Communist response proved to be even stronger. Soviet Foreign Minister Vishinsky roundly denounced the Indian plan in the United Nations, and Chou En-lai rejected it by stating on 28 November that the Russiansponsored proposal calling for forcible repatriation was the only reasonable one. When it came to a vote on 3 December, the U.N. voted down the USSR's resolution, 40 to 5, and adopted the Indian plan, 54 to 5. Only the Communist bloc supported the Russian and opposed the Indian proposal. The latter provided that if the peace conference did not settle the nonrepatriates' fate in thirty days, the prisoners would be turned over to the United Nations for disposition.10

There was small chance that the Communists would pay much heed to the action of the General Assembly in the matter beyond attacking it vigorously. But the bitter assault that they launched on the Indian suggestion served two purposes: it alienated public opinion in some of the neutral countries that had supported this solution; and it helped obscure the milder disapproval evidenced by the United States.

The unfavorable publicity garnered by the Communists on this score, however, was soon to be matched by the gathering storm of unfortunate events taking place in UNC prison camps. Although the Communist prisoners had been relocated in smaller, more manageable groups and scattered on a number of islands to lessen the threat of concerted action, the hard-core leaders and their followers had shown no disposition toward ending their fight in the compounds.

As already indicated, the problem of maintaining order and discipline in the Communist enclosures was fraught with pitfalls. A policy of leniency and laxness would allow the zealous partisans full opportunity to control and administer the compounds as they saw fit. On the other hand, a ruthless, hard policy with tight control and discipline meant continual clashes and bloodshed. The Communists seemed to welcome violence and-even more-to encourage it. For every man that the UNC was inveigled into wounding or killing meant another propaganda advantage to the enemy. The Communist prisoners acted therefore as a double weapon since they forced the UNC to maintain strong guard forces in the rear and since their agitation placed the UNC constantly on the defensive to justify its repressive measures.

When the Joint Strategic Plans and Operations Group suggested in early October that the UNC Armistice Delegation should seek to forestall Communist propaganda gains by charging the enemy with instigation of the disturbances in the camps each time one occurred, the delegation agreed that this approach had merit. But it pointed out that seizing the initiative would probably neither deter the Communists from causing the disorders nor from magnifying them to suit their purpose. The delegation felt that if the UNC intended to accuse the enemy of fomenting trouble, concrete evidence of such activity would have to be presented to substantiate the charges. This would mean that intercepted orders, confessions, plans that were uncovered, and other proof of enemy direction would have to be produced and publicized.11 The concern of the Far East Command with the enemy's techniques in exploiting the situation in the prison camps was to produce results later on, but for the time being nothing was done.

Meanwhile the enemy seldom attended a meeting of the liaison officers without citing a violation of the Geneva Convention in regard to the treatment of prisoners or an infringement of the neutral zone around Panmunjom by UNC aircraft or ground troops. On 30 November the Communists alleged that the UNC had wounded thirty-two prisoners at Koje-do five days earlier and then went on to claim that during October and November a total of 542 Communist prisoners had been killed or wounded.12 By the end of the year, General Nam charged that the UNC had caused 3,059 casualties among the Communist internees since July 1951 and noted that the Communists had lodged 45 protests on this score since February 1952.13

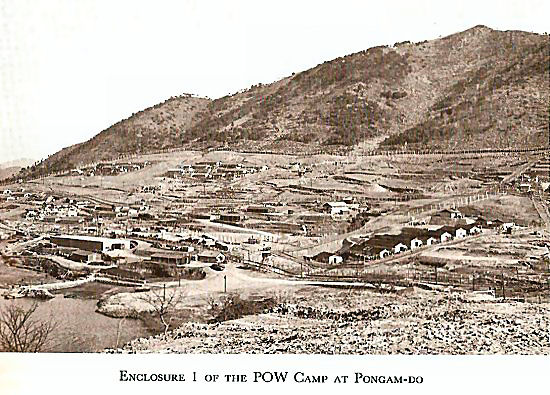

The growing toll in the prison camps caused UNC leaders a great deal of uneasiness as December began. Direct disobedience of orders was a common occurrence and was usually countered by direct application of force. Indications from the UNC Prisoner of War Command pointed to considerable planning among the prisoners for a mass breakout from the camps in early December and one of the worst trouble spots was at the civilian internee compounds on Pongam-do, a tiny island not far from Koje-do.14

It was difficult to understand why Pongam-do had been chosen for a prison camp site. The island was small and compounds had to be located on the side of a steeply terraced hill. Since the prisoners were placed on the upper terraces and access could only be gained by proceeding level by level up the hill, the Communist internees were given all the advantages of terrain. For some time, the prisoners at Pongam-do had been getting bolder and bolder. They organized and conducted military drill in defiance of UNC orders and mounted demonstrations at will. Among the 9,000 inmates on the island were many of the prisoners who had been participants in the February 1952 outbreak on Koje-do. They were guarded by one ROK security. On 14 December matters came to a head. Around 3,600 internees in six compounds were ordered to disband their drilling and to cease causing a commotion. Instead they formed three ranks on the upper terrace and locked arms. Others gathered behind this protective screen and began to hurl rocks and debris on the ROK troops as they ascended the hill to enforce the order. Ordinarily concussion grenades and nontoxic gas would have been used, but, in this instance, the prisoners could throw the grenades back down the hill and a strong crosswind ruled out the employment of gas. Thus, when orders and warning shots were disregarded, the ROK soldiers began to take aim at the solid, defiant ranks above them. At close range the bullets opened gaps in the human chain and resistance collapsed. But when the melee was over, 85 prisoners lay dead, 113 were hospitalized, and there were over 100 minor injuries. Only four ROK personnel received major wounds.15

The affair at Pongam-do again led to a flurry of activity on POW matters. Clark told Van Fleet to have available one U.S. infantry battalion that could be shifted to the Korean Communications Zone on twenty-four hours' notice and authorized General Herren to utilize one battalion of the 1st Cavalry Division on the prisoner of war mission. When Herren asked that helicopters be furnished so that tear gas grenades could be dropped on rioters to disperse them without casualties, Clark approved his request.16 These measures would help to cope with the results of the prisoner agitation if not with the causes.

To strengthen his hand against further outbreaks in the prison camps, Clark pressed anew for authority to establish a U.N. military commission to try prisoners charged with postcapture offenses. His urgings in July and August had elicited no positive action, despite the support of General Collins, but with the example of Pongam-do fresh in the news, Clark reminded his superiors that the lack of appropriate judicial machinery weakened the disciplinary powers of the camp commanders.17 In view of the legal and political complications involved in conducting trials of prisoners of war, the U.S. political and military leaders had been reluctant to use this weapon in the past, but Clark's plea reopened the matter. Speedy action approving such authority, however, appeared to be out of the question, since the JCS intended to have the entire POW problem reviewed at the highest level.18 This meant consideration by the new President and his advisors and would take time.

Pongam-do produced protests from the Communists and criticism by the International Committee of the Red Cross of the methods used by the U.N. Command. The latter complaint was more difficult to cope with, for the ICRC was highly regarded throughout the non-Communist world. In answer to the Red Cross allegation that the UNC control of prisoners had been overly strict and the members of the security forces had been unnecessarily harassing the prisoners, Clark issued a statement defending the UNC actions and attacking the Communist prisoners' behavior. He reminded the ICRC representatives that the UNC had voluntarily observed the Geneva Convention while the Communists had ignored it. When it came to deliberate disobedience, marked by mutiny, riots, or refusal to carry out orders, on the one hand, and terrorism in the camps, on the other, the UNC had used force, but only after all other methods had been tried. Clark pointed out that the UNC had constantly sought to improve the physical facilities and supply procedures for the camps and that only the pro-Communist enclosures, whose inmates had never accepted their nonbelligerent status as prisoners, had turned to organized violence.19

Despite the voluminousness of the enemy's protests during the latter part of 1952, Clark did not believe that the Communists had any intention of terminating the negotiations. The continuous barrage of enemy grievances seemed designed, in his opinion, to play upon the fears of the United States' allies and to create sympathy for the Communist position on prisoners of war.20

Nevertheless, the Far East commander took steps to lessen the opportunities of the prisoners to incite unrest. To eliminate the necessity for visiting the latrines at night, the prison command installed facilities in each barracks. In the corridors between the compounds guards were armed with shotguns so that prisoners moving around in disobedience to the camp curfew could be identified by the buckshot they absorbed, but not killed or seriously injured.21

In early January, the Department of the Army and the Far East Command decided that the time had come to expose the Communist methods and techniques of stirring up trouble in the prison camps. The Military Intelligence Section, G-2, of the FEC was assigned the task of compiling a report on the organization, control, and methods used by the enemy to exploit their faithful followers and to demonstrate the problems facing the U.N. Command as it attempted to deal with the matter. The end result was the study entitled The Communist War at POW Camps, published in late January.22 The press reaction in the United States to the release of this report was highly favorable, but complete copies were not available there and full advantage of the study could not be attained.23

The enemy seemed to hold the upper hand in the battle of indirect pressures as 1953 began. However, the UNC still retained several weapons that it had not used. In mid-December, Col. Charles W. McCarthy, senior UNC liaison officer, had urged that the UNC strike back. In a letter to the joint Strategic Plans and Operations Group he pointed out that the UNC pilots were allowing the Communists to utilize the PyongyangKaesong road for convoys to the truce area every day. In effect, what this meant, McCarthy continued, was that the enemy had a main supply route open all day despite the fact that the negotiations were in recess. He proposed that the UNC cut back the number of convoys permitted the enemy to three or less a week and require the Communists to adhere to a tight timetable for each trip allowed. Such action would strike a blow at the enemy and perhaps let the people back home know that the UNC was not adopting a passive approach to the Communists' behind-the-scenes tactics.24

Thus, when the liaison officers met on 15 January, Colonel McCarthy's successor, Col. William B. Carlock, informed Col. Ju Yon, who had recently taken Colonel Chang's place, of the new UNC policy. Starting on 25 January, the Communists would be allowed to run only two convoys a week as long as the negotiations were in recess. One would leave P'yongyang and the other Kaesong every Sunday morning; both would be required to finish their journeys by 2000. To the protest by the Communists that the UNC could not unilaterally break the agreement of November 1951, Colonel Carlock informed Ju that there was no "agreement" on the immunity granted the Communists, since the enemy had not extended any like consideration to the UNC.25

The Republicans Take Over

When Dwight D. Eisenhower became President of the United States on 20 January, John Foster Dulles succeeded Dean Acheson as Secretary of State and Charles E. Wilson became Secretary of Defense. Yet, as noted above, there was no basic change in U.S. policy insofar as the Korean War was concerned. The new administration had no panacea for ending the conflict expeditiously and no intention of expanding the military pressure to force a settlement upon the Communists. On the whole the Republicans adopted the policy of watchful waiting pursued by the Truman administration.

The new President quickly changed one of the procedures followed by Mr. Truman during his term of office. No longer were all the important messages concerning the Korean War routed across his desk for final approval. This task now fell largely to the Secretaries of State and Defense and Mr. Dulles' role in the making of Korean policy increased during the early months of 1953.

In one substantive respect, too, President Eisenhower swiftly divorced himself from the course followed by his predecessor. In his State of the Union message to Congress on 2 February, Mr. Eisenhower revealed that he had decided to end the U.S. naval blockade of Taiwan.

No longer would the U.S. Seventh Fleet serve as a screen for the Chinese Communists and prevent Chiang Kai-shek from attacking the mainland, the President affirmed. As might be expected, reaction to this shift was loud and varied. General MacArthur, Senator Robert A. Taft of Ohio, Chiang Kai-shek, and President Rhee all supported the rescinding of the restriction, while leading Democrats and prominent newspapermen in Great Britain and India immediately voiced their concern lest the act provoke an extension of the war into the Taiwan area. Backers of the President hailed the "unleashing" of Chiang's forces and praised Eisenhower for having seized the initiative in the battle with communism. But if it were true that the enemy might be confused and forced to guess at the next move that the United States might make, it was also fair to state that the sword was two-edged. It was also conceivable that the Communist Chinese might attack Taiwan.

British Foreign Secretary Eden was quite cool to the "unilateral" decision taken by the new government without consultation with its allies and warned that the move might "have very unfortunate political repercussions without compensating military advantages." In India, one newspaper accused the President of "hunting peace with a gun." 26

Despite the excitement generated by this announcement, there was no sudden outbreak of operations in the Taiwan sector. The Nationalist Chinese forces had but few landing craft and only a small number of their troops were amphibiously trained. Without greater support in equipment from the United States and the preparation of more divisions for assault landings, the Nationalist threat could become little more than a threat. The principal result of the "unleashing" was to stir up the political and diplomatic waters of the world, while those about Taiwan remained militarily serene. As the historian of the Far East Naval Forces remarked: "Despite internal uneasiness over the decision, it did not have the immediate strategic significance expected, and, tactically, had no effect on the operation of the Formosa Patrol." 27

Gradually the Eisenhower administration became more familiar with the problems in Korea and began to consider what positive steps could be taken within the accepted political framework to break the impasse. Once again the concept of unilateral release of the nonrepatriates and the presentation to the Communists of a fait accompli was revived and Clark was asked to comment on this approach. Because of the sensitivity of the matter, Clark sent a member of his staff, Lt. Col. Arthur W. Kogstad, to Washington to present his views. Meeting with Washington officials in early March, Kogstad informed the group that Clark was fully in favor of releasing the Korean nonrepatriates and did not think that such a move would have an appreciable effect upon the UNC's prospects for an armistice in Korea. As for the Chinese nonrepatriates, their disposition would require careful attention, since it would have political implications. Kogstad later reported that the tenor of opinion among the conferees attending the meeting had been favorable to Clark's recommendation, but other factors were at work. Mr. Dulles, who had a major hand in making policy in Mr. Eisenhower's administration, was busy with the U.N. General Assembly and unable to devote his time to the POW question in early March. Then, too, the sudden demise of Joseph Stalin of a cerebral hemorrhage on 5 March had injected any number of new elements into the world political picture, and time was required to assess them before bold ventures were embarked upon.28 At any rate time overtook the concept of unilateral release insofar as the U.N. Command was concerned and the next time it reared its head, it bore the visage of Syngman Rhee.29

The rash of incidents in the prison camps meanwhile continued unabated. Clark decided in February to sound out the new political chiefs on the old question of trial of prisoners for their postcapture offenses. Pointing out that the publication of the study of the Communist prisoners had raised questions among the press and his own troops as to why no disciplinary action had been taken against the prison leaders, Clark requested immediate consideration for this pressing problem.30

The Far East commander received some solace in late February. In cases of flagrant attack against UNC security personnel, the JCS told him, Clark might bring the offenders to justice, but no undue publicity would be given to the trials. This was only a halfway measure. Clark immediately protested, since most of the violence had been directed at fellow prisoners rather than at the U.N. Command. In the face of this reclama, the JCS secured authority for the UNC to try prisoners charged with offenses committed after June 1952 against other prisoners.31

Despite this apparent victory, events conspired to delay the trial and punishment of the Communist troublemakers in the prison camps. Before the Far East Command brought the first cases to court, the State Department wanted to line up judicial support and participation in the trials from the United States' allies in Korea. By the end of March, however, only four nations had agreed to serve on military commissions.32 This reluctance to share the responsibility for trying prisoners of war for postcapture offenses and the swift flow of developments on the negotiating front in late March seemed to offer small hope that the ringleaders of violence would ever come to trial.

The Communist threat to Seoul in February, discussed in the preceding chapter, produced several exchanges between Tokyo and Washington concerning the neutral city of Kaesong. Under the October 1951 agreement, Kaesong was protected from UNC attack. Yet, Clark told the JCS in early February, the enemy was using the town for restaging troops, for resupply, and as an espionage headquarters. If and when he became convinced that a major Communist offensive was in the offing, Clark wanted authority to abrogate the 1951 agreement and attack Kaesong. On 9 February, just two days after his initial request, the United Nations commander asked for permission to open up Kaesong to assault.33

When Clark's recommendation came up for discussion in Washington, Mr. Dulles urged that the U.N. Command should unilaterally abrogate the security agreement of 1951 as of a specific date and remove Kaesong and Munsan, but not Panmunjom, from a neutral status, if an enemy offensive of division size or larger seemed imminent. The JCS, in passing the decision on to Clark, pointed out that such an action would help alleviate an adverse military situation, while lessening the political implications that the negotiations were being completely broken off.34 As it turned out, the large-scale Communist offensive failed to materialize and Clark did not have to retract Kaesong's immunity.

The Big Break

Amidst the search for ways and means to apply pressure upon the enemy and to strengthen General Clark's hand in the conflict, the UNC made a rather perfunctory gesture that, at the time, seemed to offer little chance of a favorable response. Back in December, Clark had read a news despatch from Geneva which reported that the Executive Committee of the League of Red Cross Societies had passed a resolution on 13 December calling for the immediate exchange of sick and wounded prisoners. Clark suggested that, although he did not think the Communists would agree to such an exchange in the light of their previous reaction to similar proposals, he felt that the UNC should support the resolution for its psychological and publicity value.35

No action was taken on his suggestion until February. Then the State Department learned that the question of an exchange of sick and wounded would probably be raised when the U.N. General Assembly met on 24 February. The political advantage in having the United States propose and support a resolution of this nature was obvious and the State Department had little difficulty in securing the approval of the JCS and of Clark.36

On 22 February the Far East commander thus sent a letter to Kim and Peng requesting an immediate exchange of sick and injured prisoners. He believed they would turn it down, as they had earlier efforts along this line.37

The matter lay fallow during the remainder of the month and most of March. In the meantime, the enemy sustained the flow of complaints on prisoner of war incidents, infringements of the vital area by UNC aircraft, and even resurrected the charge that the UNC was resorting to germ warfare. On 24 February Clark issued a statement refuting the Chinese claim that captured American personnel had admitted the employment of germ warfare. He pointed out that Communists evidently expected new outbreaks of disease during the spring and were trying to cover up the inadequacy of their own health service to cope with epidemics. In conclusion, he reaffirmed that the U.N. command had never engaged in germ warfare in Korea.38

As March opened, events began to change the world situation dramatically. Stalin's successor, Georgi M. Malenkov, assumed the reins of government on 5 March and another transition period for world communism was inaugurated. Whether the policies of the new controlling group surrounding Malenkov would differ radically from those of Stalin was unknown, but that there would have to be a period of consolidation to establish Malenkov and his associates in power seemed self-evident. Under the circumstances, the United States and its allies cautiously awaited indications of the direction that the Malenkov regime intended to take.

Although the Communist prisoners of war seemed little affected by Stalin's death and mounted an attack on the prison commandant on the island of Yoncho-do on 7 March, which resulted in the death of twenty-three prisoners and the wounding of sixty more, there were signs that a shift in Soviet strategy might be approaching.39 On 21 March Moscow radio, for the first time since the close of World War II, admitted that the United States and Great Britain had played a role in the defeat of the Axis Powers. The Russians also agreed to intervene to obtain the release of nine British diplomats and missionaries held captive in North Korea since the outbreak of the Korean War. In Germany, the Soviet reaction to the West German ratification of the European Defense Community treaty was fairly mild.40 The possibility that a new Communist peace offensive was in the making evoked a spirit of hope in diplomatic circles throughout the non-Communist world.

The big break came on 28 March. Replying to Clark's request for the exchange of sick and wounded prisoners, Kim and Peng said that they were perfectly willing to carry out the provisions of the Geneva Convention in this respect and then went on to state: "At the same time, we consider that the reasonable settlement of the question of exchanging sick and injured prisoners of both sides during the period of hostilities should be made to lead to the smooth settlement of the entire question of prisoners of war, thereby achieving an armistice in Korea for which people throughout the world are longing." 41

What the Communist leaders meant by their vague reference to a "smooth settlement of the entire question of prisoners of war" was a matter of conjecture, but their acceptance of the sick and wounded exchange promoted optimism.

Clark immediately told the JCS that he would go ahead with the arrangements for the sick and wounded through the liaison officers, but would decline to resume plenary sessions until the enemy either came forward with a constructive proposal or demonstrated willingness to accept one of the offers that the UNC had made.42 In their reply, his superiors suggested that Clark's letter imply that the Communists intended to meet in substance the UNC position on prisoners if the negotiations were reconvened. In this way the burden would be placed upon the enemy to either agree to that assumption or admit publicly that there was no change in their stand on repatriation. In no case, the Washington leaders concluded, would the resumption of negotiations be tied in as a condition for the exchange of the sick and wounded.43 Clark followed the instructions and dispatched his response to Kim and Peng on 31 March.44

While Tokyo and Washington pondered the significance of the Communist move, Chou En-lai, Foreign Minister of Communist China, provided a measure of clarification. On 30 March he issued a statement covering the course of the negotiations and the agreements already reached. Chou then went on to the prisoner of war problem and offered what apparently was the key concession, as he urged that both sides "should undertake to repatriate immediately after the cessation of hostilities all those prisoners of war in their custody who insist upon repatriation and to hand over the remaining prisoners of war to a neutral state so as to ensure a just solution to the question of their repatriation." Lest the U.N. Command assume that the enemy had surrendered its views on repatriation, Chou strongly affirmed that the Communists believed that the prisoners of war had been filled with apprehensions and were afraid to return home "under the intimidation and with oppression of the opposite side." He was confident that once explanations could be tendered to the prisoners, they would quickly decide to be repatriated.45 At any rate, the Chou proposal, which was quickly seconded by Kim Il Sung the following day, presented the brightest hope of settling the Korean War since screening in April 1952.

The initial reaction to Chou's communication in Washington was continued caution. While not denying that it held promise, the U.S. leaders maintained that the Communists still had to come forward with a detailed plan for implementing their proposal. They could foresee a number of questions that would have to be answered such as: What did Chou mean by a "neutral" state? Where would the neutral state take over control of the prisoners- in or outside of Korea? Who would make the explanations? Who would determine the final disposition of the nonrepatriates? If the Communists went forward with the exchange of sick and wounded and produced a detailed statement indicating their good faith in desiring a settlement of the over-all problem, the American leaders were willing to permit concurrent discussion of Chou's proposal during the exchange.46

Clark agreed fully that the enemy must produce a concrete plan for discussion before the plenary sessions could reconvene and that the Communist performance in following through on the sick and wounded trade would provide a demonstration of their good faith. In a letter to the enemy leaders on 5 April, he proposed that the liaison officers meet the following day and requested that Kim and Peng furnish the UNC with more particulars on the Communist method for disposition of the nonrepatriation question.47

In preparation for the first meeting of the liaison officers on the arrangements for the transfer of the sick and wounded, Clark and his staff formulated a UNC plan. It contemplated that each prisoner to be exchanged would be brought to Panmunjom, furnished with a medical tag on his condition and treatment and given unmarked, serviceable clothing. No incapacitated prisoner accused of postcapture war crimes would be held back for this reason, since it did not appear probable now that war crimes trials would ever be held. To insure that the enemy return the maximum number of UNC personnel, Clark told Harrison to avoid the use of the term "seriously" sick and wounded. As for the treatment of the prisoners turned back to the UNC through the exchange, Clark wanted to permit the members of the press and other news media to observe the whole process, but to restrict their numbers to fifty at Panmunjom and to allow interviews only with the prisoners selected by medical personnel as physically and mentally up to being questioned.48

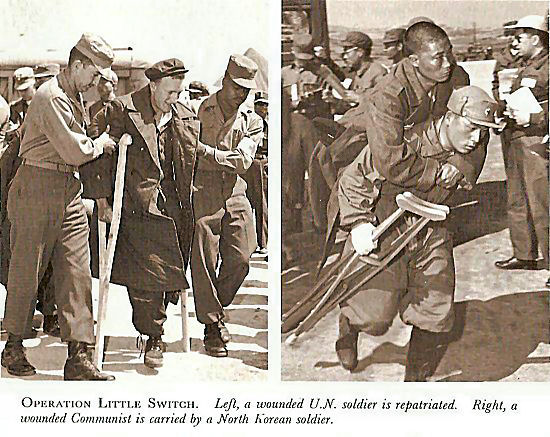

Operation LITTLE SWITCH

Admiral Daniel and General Lee Sang Cho led the liaison officers groups when they gathered at Panmunjom on 6 April. Relieved of the task of lodging and refuting charges and complaints, the representatives quickly got down to business and Admiral Daniel launched into an account of the UNC proposal. The United Nations Command was ready to start immediate construction of the facilities necessary for the delivery and receipt of the sick and wounded at Panmunjom and to begin delivery of 500 prisoners a day within seven days of the agreement on procedures. To expedite matters Daniel suggested that each side turn over its lists of names and nationalities of the prisoners to be exchanged and that officers be appointed to discuss administrative details. Lee pointed out that the Communists wanted to repatriate all sick and wounded eligibles under Articles 109 and 110 of the Geneva Convention.49

After some hesitation, while the UNC checked the Geneva Convention carefully, Daniel informed the Communists on 7 April that his side was prepared to repatriate all prisoners eligible under the two articles, subject to the proviso that no individual would be repatriated against his will. Daniel stressed that the UNC would give the broadest interpretation possible to the term "sick and wounded."50

The effort of the United Nations Command to encourage the enemy to return as many prisoners as possible met with a disappointing response. When Lee announced the total on 8 April of 450 Korean and 150 non-Korean sick and wounded, Daniel called the figure "incredibly small." Actually, considering that the enemy was returning 600 of the 12,000 prisoners under its control, or 5 percent, the figure compared favorably with that presented by the UNC. For the latter intended to transfer 800 Chinese and 5,100 Koreans over to the enemy out of the 132,000 prisoners in its custody and this averaged out to only about 4.5 percent. Nevertheless, Daniel again asked the Communists to be more liberal in their classification of the sick and wounded.51 As he told Clark after the meeting, the enemy liaison officers relaxed their strained attitudes visibly after the UNC disclosed its figures and he felt that he should press strongly for an increase in the totals the UNC would receive.52

In the succeeding days the details were gradually worked out. Security guards at Panmunjom were increased to thirty for each side during the exchange period and the UNC agreed to let the Communists move the prisoners up to the conference area in convoys of five vehicles over routes that were clearly marked out.53

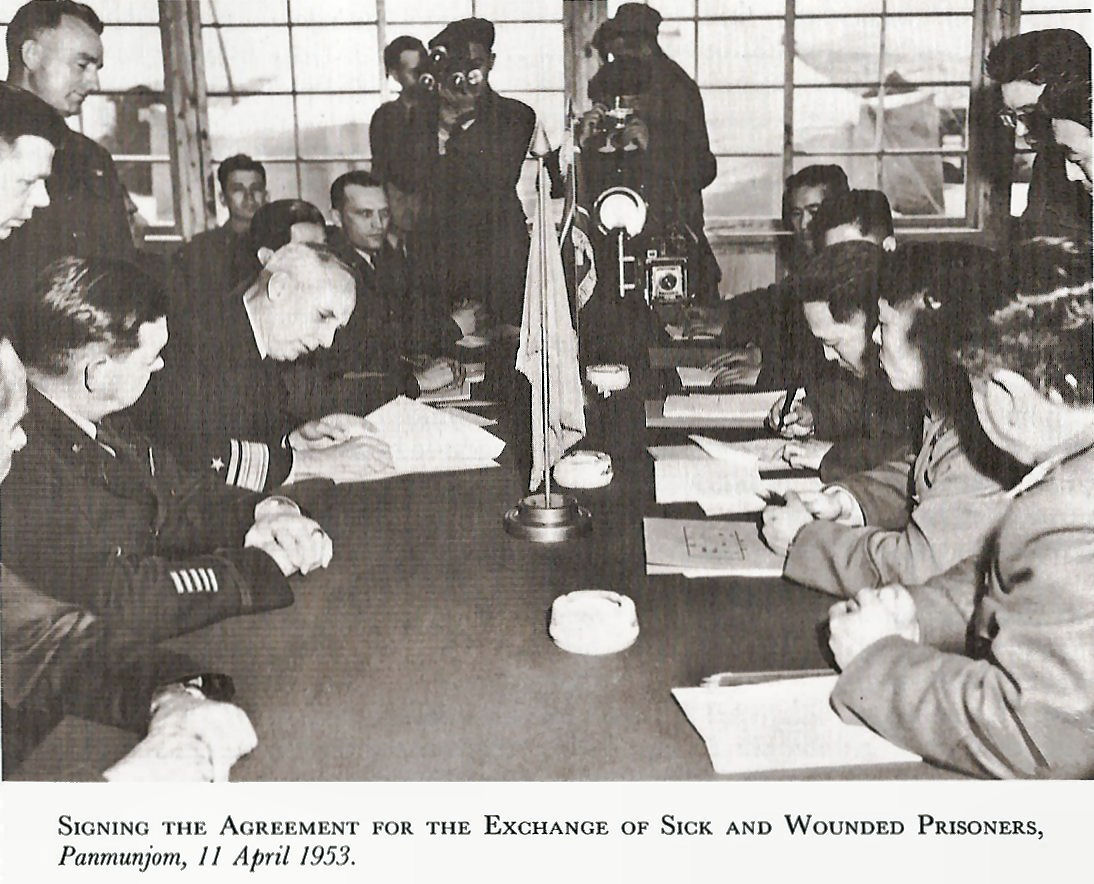

The agreement that was signed on t t April completed the general arrangements. Within ten days the exchange at Panmunjom would begin, with the enemy delivering 100 and the UNC 500 a day in groups of 25 at a time. Rosters prepared by nationality, including name, rank, and serial number would accompany each group and receipts would be signed for a group as it was turned over to the other side.54

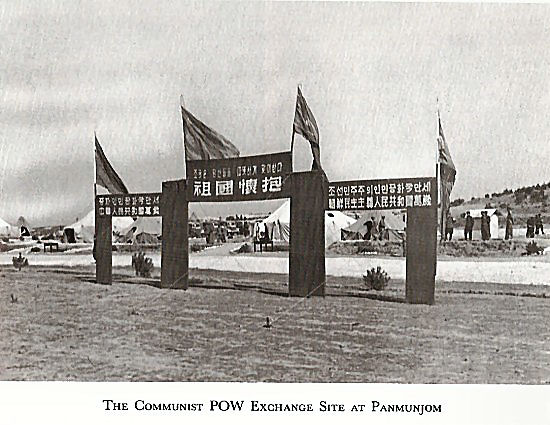

April 20 was established as the date for initiating LITTLE SWITCH, as the U.N. Command dubbed the operation, and in the interim trucks and trains began to transport the Communist prisoners north from Koje-do and the other offshore islands. On 14 April, twenty-three vehicles left the North Korean prison camps with the first contingent of UNC sick and wounded. Five days later the first trainload of enemy prisoners set out from Pusan to Munsan. But even as the Communist invalids prepared to go home, they sought to embarrass the UNC. Some refused a new issue of clothing because the letter "P" for prisoner had not been stenciled on the shirts. Others would not permit UNC personnel to dust them with DDT powder. Demonstrations broke out, with chanting and singing, until camp authorities warned the leaders that failure to obey orders would result in loss of their opportunity for repatriation. As the prisoners rode to the waiting LST for shipment to the mainland, they threw away their rations of tooth powder, soap, and cigarettes with hand-printed propaganda messages cached inside, charging the United States with "starvation, oppression and barbarous acts against the Korean people." At Pusan they demanded the right of inspection of hospital facilities before they debarked and had to be told they would be forcibly removed unless they complied with instructions. Some of the Chinese went on a hunger strike for several meals because they claimed that the food had been poisoned. When the time came for the final train ride from Pusan to Munsan, many of the prisoners cut off buttons, severed the half-belts of their overcoats, and removed their shoelaces in an attempt to create the impression that they had been poorly treated.55

As the U.N. Command gathered all of the Communist prisoners eligible for return, it discovered that there were more than 5,800 who could be repatriated. The question immediately arose whether to include the additional 550 Communists in the exchange or to adhere to the original tally. General Clark felt that the advantages of demonstrating the good faith of the UNC and of possibly spurring the enemy to increase its total of returnees outweighed the disadvantages of introducing a new figure and his superiors agreed.56

A new element was injected into the situation after LITTLE SWITCH got under way on 20 April. When the UNC sick and wounded were delivered to Panmunjom they were rushed back to Munsan for initial processing. Some were then flown to Japan for rest and treatment preparatory to shipment home, while the ROK patients were transferred to base hospitals in South Korea. As the press descended upon the prisoners for accounts of their experiences while in Communist hands, stories arose of other ill and injured prisoners still remaining in the enemy camps. Harrison quickly suggested that the UNC use the 550 extra Communist prisoners as a lever to pry more UNC personnel away from the enemy. But Clark preferred that Harrison simply ask the Communists to reexamine the matter, since many prisoners might not be in a fit condition to be moved.57

Whether the enemy was influenced by the UNC revelation that it was going to turn over 550 more patients than originally estimated, or by the uproar that the press stories of the UNC sick and wounded reportedly still in Communist custody occasioned in the United States, was difficult to ascertain. On 23 April, however, the Communists did announce that they would also exceed the 600 figure that they had submitted.58

Hoping to encourage further relaxation of the Communists' standards, the UNC added more enemy prisoners to its list, but on 26 April General Lee abruptly stated that his side had completed its share of the exchange. When Admiral Daniel protested that evidence in UNC possession showed that there were still about 375 UNC sick and wounded who could be repatriated, Lee termed it a groundless accusation and refused to consider the matter. Faced with an unyielding stand, the U.N. Command on 3 May finished delivering the last group of Communists that it intended to turn over.59

The final tally of deliveries disclosed that the UNC had relieved itself of 5,194 North Korean and 1,030 Chinese soldiers and 446 civilian internees, for a total of 6,670. Of these patients 357 were litter cases. In return the enemy had brought 684 assorted sick and wounded, including 94 litter cases, to Panmunjom.60

Perhaps the Communists had not been as liberal as many had hoped, but at least they had carried out their part of the bargain and thrown in a small bonus. In the light of this performance and the apparent disposition of the enemy to put an end to the shooting war in Korea, the resumption of plenary negotiations seemed to be in order.

Preparations for the Return to Plenary Sessions

While the Communists were evidencing their sincerity in following through with the LITTLE SWITCH exchange, General Clark and his advisors sought to find out more about the intent and extent of the concession that Chou had offered on 30 March. As already pointed out, the Chinese statement had produced a mixed atmosphere of hope and caution throughout the non-Communist world, but it had been couched in such vague terms that it generated more questions than it answered. Clark's letter to Kim and Peng on 5 April had asked for further details and clarification.

The response came from Nam Il rather than his superiors on 9 April. Repeating in essence the same line that Chou had used about the Communist desires to find a peaceful solution to the conflict and to permit the prisoners to return home quickly, Nam went on:

It is precisely on the basis of this principle of repatriation of all prisoners of war that our side firmly maintain that the detaining side should ensure that no coercive means whatsoever be employed against all the prisoners of war in its custody to obstruct their returning home . . . . The Korean and Chinese side does not acknowledge that there are prisoners of war who are allegedly unwilling to be repatriated. Therefore the question of the so-called 'forced repatriation' or 'repatriation by force' does not exist at all, and we have always opposed this assertion. Based on this stand of ours, our side maintains that those captured personnel of our side who are filled with apprehensions and are afraid to return home as a result of having been subjected to intimidation and oppression, should be handed over to a neutral state, and through explanations given by our side, gradually freed from apprehensions . . . .61

Based on Nam's reply, the problem was quite simple-if the U.N. Command would stop trying to detain the prisoners forcibly and would hand them over to a neutral nation, the Communists would soon convince the so-called nonrepatriates of the needlessness of their fears and all would be glad to go home. It was a glib attempt to save face and dismiss their concession as only procedural and not substantive.

Although Nam's letter failed to answer the questions that the Washington leaders had raised earlier on the identity of the neutral nation or on the treatment of the nonrepatriates once they were surrendered to the neutral nation, these were details that the plenary conference would have to settle. But to maintain the initiative, the UNC notified Nam on 16 April that since his letter had not offered concrete proposals, it assumed that the Communists were either ready to accept one of the UNC's earlier plans or to offer a constructive one of their own. To prepare the enemy with some idea of what the UNC considered constructive, Harrison cited Switzerland as a neutral state in view of its long tradition in this respect and urged that the neutral state take custody of the nonrepatriates in Korea itself. As for the time limit for persuading the nonrepatriates to come back home, sixty days appeared sufficient. In closing Harrison warned that if the plenary meetings did not give promise of an acceptable agreement within a reasonable time, the UNC would recess them again.62

On the eve of the LITTLE SWITCH Operation, Admiral Daniel proposed 23 April as a date for the resumption of plenary conferences, but the Communist representative preferred 25 April. Later on they postponed the opening date to 26 April.63

The few days before the first meeting proved a busy period of last-minute preparations and instructions. Clark told Harrison to reject the Soviet Union or any of its satellites as candidates for the neutral state role and to insist upon the retention of the nonrepatriates in Korea. In response to the Far East commander's request for acceptable nominations for the neutral state, his superiors advanced Switzerland and Sweden in that order. They felt that he could agree to a go-day limit for the custody of the nonrepatriates by neutral nations. As a talking point, General Collins told Clark that the U.N. Command should emphasize the fact that it had the absolute legal right to grant asylum and was making a major concession in permitting a neutral nation to assume control of the nonrepatriate prisoners.64

To acquaint Clark with current policy on a Korean settlement, the JCS forwarded some basic instructions on 23 April for his guidance. The first two items were direct inheritances from the previous administration and reaffirmed that it was to the interest of the United States to obtain an acceptable armistice, yet not at the expense of a compromise on the principle of no forced repatriation. Until proved to the contrary, the instructions stated, the Communist proposal would be taken at its face value; however, the United States would not countenance long and inconclusive haggling. Since the UNC had seized the initiative through the Harrison suggestions of 16 April, it should strive to retain this favorable position to keep the enemy on the defensive. Any of the former plans submitted by the UNC would be satisfactory as a basis for agreement, but it might be desirable to confine the task of processing nonrepatriates to the Chinese and to release the North Koreans without further processing, the instructions concluded.65

Thus, in the six months of recess, the top political personnel in the United States had been replaced, but the politics lingered on. The new leaders had tried several minor expedients to induce the Communists to halt the fighting in Korea and the enemy had reciprocated with its own brand of pressure. Under ordinary circumstances, this game could have been played indefinitely, without reaching a decision. But, with the death of Stalin, the balance shifted to the advantage of the U.N. Command. It would appear from Soviet actions in March and April that the removal of external distractions such as the Korean affair with its drain on Russian resources acquired a new sense of urgency during the period of consolidation of power. As part of the new peace offensive, or as Secretary Dulles termed it, peace "defensive," launched after Stalin's demise, the Communists' concession on the nonrepatriate question dangled the hope of a settlement before the eyes of the United States and its allies.66 Based on past experience, however, the UNC was properly cautious as it prepared to discover just what the Communists had in mind. The brightening prospect for an armistice was tempered by the rising tide of opposition in South Korea to any agreement that accepted a disunited Korea. In the critical days that lay ahead the UNC might well find it more difficult to deal with the dissension behind its lines than with the enemy.

Notes

1 Msg, JCS 920838, JCS to CINCFE, 11 Oct 52.

2 (1) Ltr, Harrison to Nam, 15 Oct 52, no sub. (2) Ltr, Clark to Kim and Peng, 19 Oct 52. Both in G-3 File, Liaison Officers Mtgs Held at Pan Mun Jom, 1952, bk. II.

3 Ltrs, Nam to Harrison, 16 and 29 Oct 52, no sub, in G-3 File, Liaison Officers Mtgs Held at Pan Mun Jom, 1952, bk. II.

4 From the context it is evident that Secretary Acheson used the term "UNC" loosely, encompassing the political and military leadership in the U.S. and other allied U.N. countries. As already noted, General Ridgway had had misgivings about the UNC position on voluntary repatriation before it became the official stand. See Chapter VII, above.

5 Department of State Publication 4771, The Problem of Peace in Korea, a report by Secretary of State Dean Acheson, October 24, 1952 (Washington, 1952).

6 G-3 and State Dept Staff Paper, no title, no date (ca. 28 Oct 52) , in G-3 091 Korea, 3/22.

7 Memo, Bradley for Secy Defense, 17 Nov 52, sub: U.S. Position on Korea . . . .

8 Msg, DA 924505, G-3 to CINCFE, 22 Nov 52.

9 (1) Msg, DA 924551, G-S to CINCFE, 23 Nov 52. (2) U.S. Reaction to India's Proposal on Prisoners of War, Statement made by Secretary Acheson, in Dept of State Bulletin, vol. XXVII, No. 702 (December 8, 1952) , pp . 910ff.

10 Text of Resolution on Prisoners of War, 3 Dec 52, in Dept of State Bulletin, vol XXVII, No. 702 (December 8, 1952) , pp . 916-17. 11 Ltr, Col S. D. Somerville, Exec to UNC Delegation, to Chief JSPOG, 14 Oct 52, sub: Letter on POW Incidents, in FEC SGS Corresp File, 1 Jan-31 Dec 52.

12 Memo for Rcd, sub: Liaison Officers' Mtgs, 30 Nov 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Nov 52, incls 1-89, incl 1.

13 Ltr, Nam to Harrison, 30 Dec 52, no sub, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Dec 52, incls 1-78, incls 1 and 2.

14 Msg, CX 59869, CINCUNC to DA, 8 Dec 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Dec 52, incls 1-78, incl 6.

15 Msg, CX 60206 and CX 60301, CINCUNC to DA, 15 and 18 Dec 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Dec 52, incls 1-78, incl 8.

16 (1) Msg, CX 60234, CINCFE to CG Eighth Army, 16 Dec 52. (2) Msg, CX 60303, CINCFE to CG Eighth Army, 18 Dec 52. Both in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Dec 52, incls 1-78, incls 9 and 10.

17 Memo, Eddleman for CofS, 19 Dec 52, sub: Trial of POW's for Post-Captive Offenses, in G-3 383.6, 64.

18 Msg, JCS 928298, JCS to CINCFE, to Jan 53.

19 (1) Msg, C 60412, CINCFE to DA, 21 Dec 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Dec 52, incls 1-78, incl 19. (2) Msg, CX 60820, CINCUNC to CSUSA, 5 Jan 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jan 53, incls 1-67, incl 16.

20 Msg, CX 60789, CINCFE to JCS, 2 Jan 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jan 53, incls 1-67, incl 15.

21 (1) Msg, CX 60811, CINCUNC to Herren, 3 Jan 53. (2) Msg, AX 72028, Herren to Clark, 8 Jan 53. Both in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jan 53, incls i-67, incls 17 and 18.

22 Msg, DA 928223, DA to CINCFE, 9 Jan 53.

23 (1) Msg, ZX 35682, CINCFE to DA, 28 Jan 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jan 53, incls 1-67, incl 23. (2) Msg, DA 930068, DA to CINCFE, 30 Jan 53.

24 Ltr, McCarthy to Col Donald H. Galloway, Deputy Chief JSPOG, 16 Dec 52, no sub, in FEC SGS Corresp File, 1 Jan-31 Dec 52.

25 Ltr, Carlock to Ju, 15 Jan 53, no sub. (2) Ltr, Ju to Carlock, 21 Jan 53, no sub. (3) Liaison Officers Mtgs, 21 Jan 53. All in G-3 File, Liaison Officers Mtgs Held at Pan Mun Jom, Jan-Jun 53, bk. III.

26 The reaction to the 2 February speech may be found in the New York Times, February 3, 4 1953.

27 COMNAVFE, Comd and Hist Rpt, Jan, Feb 53, p. 4.

28 A good account of the Kogstad mission will be found in Hq UNC/FEC, Korean Armistice Negotiations (May 52-Jul 53), vol. g, pt. 1, pp. 271ff. See also Clark, From the Danube to the Yalu, p. 262.

29 See Chapter XX, below.

30 Msg, CX 61135, CINCUNC to DA, 4 Feb 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Feb 53, incls 1-88, incl 15.

31 (1) Msg, DA 931969, JCS to CINCFE, 21 Feb 53. (2) Msg, CX 61323, CINCUNC to DA, 24 Feb 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Feb 53, incls 1-88, incl 17. (3) Msg, JCS 932476, JCS to CINCFE, 28 Feb 53.

32 (1) Msg, JCS 933135, JCS to CINCFE, 7 Mar 53. (2) Msgs, CX 61627 and CX 61647, CINCUNC to G-3, 25 and 27 Mar 53. Both in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Mar 53, incls 1-72, incls 13 and 14.

33 Msgs, CX 61160 and CX 61173, CINCUNC to JCS, 7 and 9 Feb 53, in JSPOG Staff Study No. 495, in JSPOG Files.

34 (1) Memo, Eddleman for CofS, 12 Feb 53, sub: Abrogation of Security Agreement Re Kaesong-Panmunjom-Munsan, in G-3 091 Korea, 12/4. (2) Msg, JCS 931311, JCS to CINCFE, 14 Feb 53.

35 Msg, CX 6008, CINCUNC to G-3, 21 Dec 52, DA-IN 220029.

36 (1) Memo, Eddleman for CofS, 16 Feb 53, sub: Proposal to Exchange Sick and Wounded POW's, in G-3 3836, 13/4. (2) Msg, JCS 931724, JCS to CINCFE, 19 Feb 53. (3) Msg, CX 61281, Clark to DA, 19 Feb 53, DA-IN 239084.

37 (1) Msg, CX 61281, Clark to DA, 19 Feb 53, DA-IN 239084. (2) Ltr, Clark to Kim and Peng, 22 Feb 53, no sub, in G-3 file, Liaison Officers Mtgs Held at Pan Mun Jom, Jan-Jun 53, bk. III.

38 Msg, Z 35882, CINCFE to DA, 24 Feb 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Feb 53, incls1-88, incl 7.

39 Msg, EX 13188, CG AFFE to DA, g Mar 58, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Mar 58, incls 1-72, incl 16.

40 New York Tines, March 20, 21, 25, 1958.

41 Ltr, Kim and Peng to Clark, 28 Mar 58, no sub, in G-3 file, Liaison Officers Mtgs Held at Pan Mun Jom, Jan-Jun 53, bk. III.

42 Msg, CX 61673, Clark to JCS, 29 Mar 53, DA-IN 252152.

43 Msg, JCS 935136, JCS to CINCUNC, 30 Mar 53.

44 Ltr, Clark to Kim and Peng, 31 Mar 53, no sub, in G-3 file, Liaison Officers Mtgs Held at Pan Mun Jom, Jan-Jun 53, bk. III.

45 Statement of Chou En-lai, 30 Mar 53, in G-3 file, Liaison Officers Mtgs Held at Pan Mun Jom, Jan-Jun 53, bk. III.

46 Msg, JCS 935344, JCS to CINCUNC, 1 Apr 53. The message was drafted by the State Department and approved by the Services, General Bradley, and the Department of Defense.

47 (1) Msg, C 61723, Clark to JCS, 3 April 53, DA-IN 253841. (2) Ltr, Clark to Kim and Peng, 5 Apr 53, no sub, in G-3 file, Liaison Officers Mtgs Held at Pan Mun Jom, Jan-Jun 53, bk. III.

48 (1) Msgs, CX 6174, and 61743, Clark to JCS, 4 Apr 53, DA-IN's 254454 and 254434 (2) Msg, CX 61751, CINCUNC to CINCUNC (Adv), 4 Apr 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 53, incls 1-256, incl 7. (3) Msg, CX 61767, Clark to DA, 6 Apr 53, in same place, incl 48.

49 First Meeting of Liaison Group for discussing arrangement for repatriation of sick and wounded captured personnel, 6 April 53, in G-3 file, Transcript of Proceedings, Meetings of Liaison Group, 6 April-2 May 1953. All the meetings of the group are in the above file and will be henceforth referred to only by number and date.

50 Second Mtg, Liaison Group, 7 Apr 53.

51 Third Mtg, Liaison Group, 8 Apr 53.

52 Msg, HNC 1611, CINCUNC (Adv) to CINCUNC, 8 Apr 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 53, incls 1-256, incl 20.

53 Fourth and Fifth Mtgs, Liaison Group, 9-10 Apr 53.

54 Sixth Mtg, Liaison Group, 11 Apr 53.

55 Msg, PWCG 4-386, POW Comd to AFFE, 19 Apr 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 53, incls 1-256, incl 106.

56 Msg, HNC 1684, CINCUNC to DA, 20 Apr 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 53, incls 1-296, incl 111. (2) Msg, JCS 986998, JCS to CINCFE, 20 Apr 53.

57 (1) Msg, HNC 1687, CINCUNC (Adv) to CINCUNC, 21 Apr 53. (2) Msg, C 62028, CINCUNC to CINCUNC (Adv), 22 Apr 53. Both in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 53, incls 1-256, incls 114 and 117.

58 (1) Msg, C 62042, Clark to DA, 23 Apr 53. (2) Msg, HNC 1639, Harrison to CINCUNC, 23 Apr 53. Both in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 53, incls 1-256, incls 121 and 122.

59 Tenth and Eleventh Mtgs, Liaison Group, 1 and 2 May.

60 UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 53, app. I, p. 51. A breakdown of the UNC and Communist repatriates and nonrepatriates involved in the prisoner of war exchanges in 1953-54 will be found in Appendixes B-1 and B-2.

61 Ltr, Nam to Harrison, 9 Apr 53, no sub, in G-3 file, Transcripts of Proceedings, Mtgs of Liaison Group at Pan Mun Jom, 6 Apr-2 May 53.

62 Ltr, Harrison to Nam, 16 Apr 53, no sub, in G-3 File, Liaison Officers Mtgs Held at Pan Mun Jom, Jan-Jun 53, bk. III.

63 Seventh Mtg, Liaison Group, 19 Apr 53.

64 (1) Msg, C 62022, CINCUNC to DA, 22 Apr 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 53, incls 1-256, incl 182. (2) Msg, JCS 937205, JCS to CINCUNC, 23 Apr 53. (3) Msg, DA 937371, CSUSA to CINCUNC, 24 Apr 53.

65 Msg, JCS 937205, JCS to CINCUNC, 23 Apr 53.

66 For Dulles' views on the Soviet shift in tactics, see his address of 18 April 53, reprinted in the Dept of State Bulletin, vol. XXVIII, No. 722 (April 27, 1953), pp. 603-08.

Causes of the Korean Tragedy ... Failure of Leadership, Intelligence and Preparation