History  On Line

On Line

After the bitter fighting of October and early November 1952, the approach of another winter witnessed a rapid decline in the scale of operations at the front. The enemy retired into his deep bunkers and caves to hibernate, and action settled down to the old routine of raids, patrols, and small unit skirmishes. Waiting patiently for a break in the recessed armistice negotiations, both sides seemed content to watch each other warily along the battle lines and to conserve their energy. The slackening of operations permitted the enemy to replenish his supplies and to bring up replacements, despite the efforts of the UNC air forces to destroy Communist depots and communications lines. But the build-up appeared to be perfunctory and not directed toward the resumption of largescale fighting. As the cold weather set in, its influence dominated the front.

The Demise of Military Victory

Despite the stalemate, General Clark had not given up all hope of mounting a large-scale operation against the enemy. During the flare-up of activity in October, he had voiced his concern to the Chief of Staff that the UNC failure to achieve an armistice stemmed from the lack of sufficient military pressure upon the Communists. With the forces presently at his disposal, Clark told Collins, positive aggressive action was not feasible, but he had developed an outline plan of action that would compel the enemy to seek or accept an armistice. If the JCS would approve the outline plan, he went on, the FEC staff could draw up supporting plans.1

In mid-October, a task force of three FEC officers arrived in Washington to explain and defend Clark's proposal. Basically it was a drive to the P'yongyang-Wonsan line in three phases, each lasting about twenty days. It included enveloping drives by ground forces, a major amphibious assault, airborne action as opportunities developed, and air and naval action against targets in China. To expand the war would require an accompanying augmentation of the FEC forces and the tally was impressive. Three U.S. or U.N. divisions (1 infantry, 1 airborne, and 1 Marine), 2 ROK divisions, 2 Chinese Nationalist divisions, 12 field artillery battalions, and 20 antiaircraft artillery battalions would be required in addition to those already in the U.N. Command to sustain the offensive successfully.2

According to Clark's later account, every subordinate commander in the FEC "heartily endorsed this course of action." With the possibility of a change in the political administration in the United States and the elevation of a military man to the leadership of the country's affairs, the prospects of an additional effort to wind up the Korean War did not seem to be far-fetched. As Clark remarked later on, "I knew we had to be ready with the plan if the turn of events called for a more vigorous prosecution of the war.3

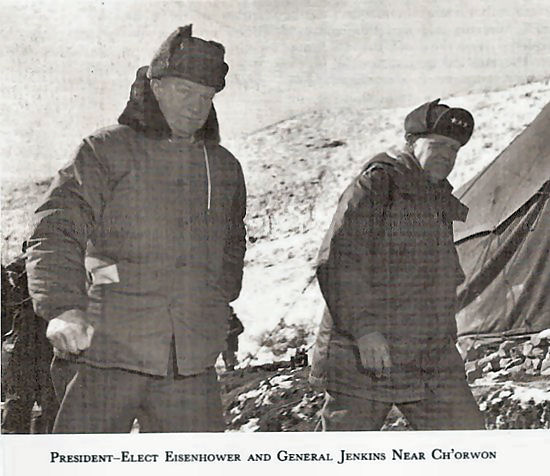

The military leaders of the FEC were doomed to disappointment. Presidentelect Eisenhower arrived in Korea on 2 December with a large and distinguished party, including the Secretary of Defense-designate, Charles E. Wilson, General Bradley, and Admiral Radford. He toured the front and visited President Rhee, talking with a great many people on the scene, but never once did he bring up the matter of seeking a military victory in Korea. Speaking to a press conference at Seoul on the last day of the visit- 5 December- the Presidentelect admitted that he had "no panaceas, no tricks" for bringing the war to a close. The most significant thing about Eisenhower's visit, in Clark's opinion, was that he, Clark, was given no opportunity to set forth the detailed estimate of forces required and the plans formulated to increase the military pressure upon the enemy. The conversations with General Eisenhower clearly demonstrated to Clark that the new President would follow the course set by Mr. Truman and seek an honorable peace.4 Thus died the last hope for a military settlement to be won by the force of UNC arms; it was evident that the political leaders, whether they were Democratic or Republican, intended to negotiate an end to the conflict.

As long as the desire to negotiate was not matched by a willingness to concede, the future course of the war seemed likely to be a repetition of what had gone before. The enemy had taken losses in October that had cut its estimated strength from 1,008,900 to 972,000 at the end of the month.5 But when the fighting tapered off in November, the enemy total began to climb slowly once again.

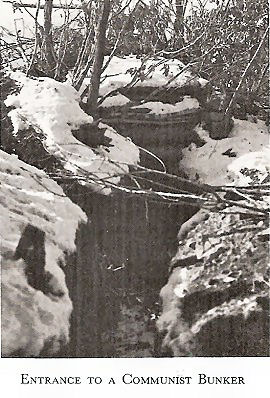

Reports from the front indicated that the Communists were digging in to stay. Although it took from three to five months to excavate their large caves, they steadily hollowed out space for squads and platoons in the bowels of strategic hills. Here, protected from UNC air and artillery as well as cold weather, the enemy could comfortably sit out the winter. Interrogation of prisoners revealed no knowledge of a general offensive, and the disposition of enemy forces along the front gave no indication of other than a usual defensive alignment. On the immediate front there were 7 Chinese armies with 166,000 men and 2 North Korean corps of 49,800 soldiers on 1 November 1952; the latter anchored the extreme eastern end of the line. (See Map V) Ten Chinese armies containing over 350,000 troops and 4 North Korean corps with about 140,000 soldiers were in reserve positions where they could either reinforce the front or defend against possible amphibious landings by the UNC. Facing them were eighteen UNC divisions and their supporting troops totaling about 350,000 men.6

As the ground operations fell off in mid-November, Communist road traffic mounted as the enemy strove to rebuild his stocks. More enemy aircraft began to appear over North Korea, but they showed little sign of increasing aggressiveness. Of the 1,227 planes sighted during the month, only 395 engaged UNC aircraft with estimated enemy losses of 21 destroyed, 4 probably destroyed, and 19 damaged.7 The enemy made one major relief in November, moving the CCF 47th Army into the Imjin River sector and the 39th Army back into reserve. On the UNC side, the U.S. 25th Division took over the positions of the U.S. 7th Division on 12 November and the ROK 9th Division relieved the ROK 2d Division on 24 November; both of these changes were routine as the U.S. IX Corps rotated its divisions on the line. |

|

The IX Corps

The U.S. IX Corps had taken the brunt of the Chinese attacks at White Horse, Triangle Hill, and Jackson Heights during October, but the pressure along the corps front eased after midNovember. Only in the Sniper Ridge sector north of Kumhwa did the Chinese continue to demonstrate their sensitivity to ROK possession of outposts on the hill.

On 2 December an enemy platoon probed the ROK 9th Division outposts on Sniper Ridge and a second platoon joined in the action. Intense fire from artillery and mortars was exchanged for a time, and then the Chinese advanced and took over the crest. But the UNC artillery concentrations soon made enemy possession of the newly won positions too costly. As the enemy withdrew, the ROK forces returned to the outposts. A brief respite followed, then a second Chinese attack led to a hand grenade duel. Once again the ROK defenders fell back. On the next day two ROK platoons carried on a seven-hour battle with the enemy before regaining the crest. During the ensuing ten days, the Chinese launched 40 probes against Sniper Ridge without success. It is interesting to note that of the 114 probes reported along the corps front during December, the Chinese directed 105 against the ROK 9th Division.8

The pattern held steadily through January as the Chinese sent frequent probes of up to three platoons in strength against the Sniper Ridge outposts with no success. Outside the ROK 9th Division area, the Chinese were hard to find. The IX Corps divisions sent out 2,668 night patrols during the month of January and reported only 64 engagements initiated by these patrols.9

In February and March the corps dispatched over 2,500 patrols to raid, ambush, or reconnoiter and fewer than a hundred made any contact with the enemy. All of March witnessed the capture of only one prisoner of war by a patrol.10 Neither side showed any inclination to disturb the quiet state of affairs on the central front and IX Corps was able to effect two routine division reliefs-one at the end of December when the ROK 2d Division moved into the U.S. 3d Division positions and the other a month later when the U.S. 3d came back into the line and permitted the U.S. 25th Division to pull back into corps reserve -without incident. (Map VI)

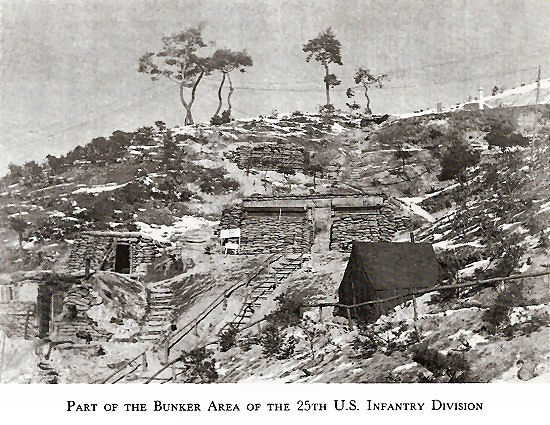

What was life like in the average infantry company during the last winter? I Company, 35th Infantry Regiment, 25th Division, was a typical example.11 About six miles northeast of Ch'orwon, the 3d Battalion of the regiment manned main line of resistance positions, with B Company, 1st Battalion, attached, holding the left flank, I Company the middle, and K Company the right flank of the battalion front. I Company's positions extended 1,500 yards from the broad floor of a valley to the crest of a northsouth ridge more than loo meters above the valley. Because of the wide front, all three rifle platoons were stationed on the main line. This meant that the company headquarters and mortar crews were the only force located on the reverse slopes of the hilly portion of the front and had to assume the counterattack role usually assigned to a support platoon.

Elements of the 130th Regiment, 44th Division, CCF 15th Army, controlled the higher terrain to the north of I Company and enjoyed excellent observation of all the company positions, especially those located on the valley floor. In the hilly area on the eastern end of the company front, the Chinese positions were only 500 yards distant. As usual, the enemy had constructed the bulk of his bunkers and trenches on the reverse slopes and carefully camouflaged the openings on the forward slopes whence he fired his weapons.

Since October 1952 1st Lt. Travis J. Duerr had commanded the company and he was one of the few officers in the unit who had some combat experience. Under him were 5 officers, 174 enlisted men, and 48 KATUSA's. One officer and 13 enlisted men were Negro, 10 were Puerto Ricans, one was a native Irishman, and one a native Hawaiian.

Lieutenant Duerr distributed the KATUSA personnel along the front line, assigning each Korean to an American "buddy." The "buddy" system enabled the Americans to train and supervise the Koreans in U.S. methods, care of weapons, and at the same time to teach his "buddy" some words of English. For the most part, the language barrier prevented the two from becoming close friends and, in I Company, many Americans adopted a paternalistic or patronizing attitude toward their "buddies."

The company had 39 bunkers placed at intervals across the front; 34 contained automatic weapons and 5 were used as living quarters only. Many of the fighting bunkers were divided into fighting and living quarters housing from two to seven men. Eighty percent of each bunker was underground and could be entered from the trenches which linked the entire front in this sector. Thick logs and sandbags covered by a burster layer of loose sand, stones, and sticks protected the bunker roofs from artillery and mortar hits. In some instances the bunkers had been originally located close to the topographical crests of the hills rather than on the military crests and had not been moved. In others the steep, uneven nature of the terrain permitted the automatic weapons sited in these bunkers only limited fields of grazing fire.

Since I Company defended an extended front, it had additional automatic weapons on hand to cover the enemy approach routes. One .5ocaliber, six .3o-caliber heavy, and twelve .30-caliber light machine guns were backed by fifteen automatic rifles in the bunkers. Three 57mm. recoilless rifles, three 3.5-inch rocket launchers, and two M2 flame throwers were located in open emplacements. The .50-caliber machine gun, five of the heavy .30's, and six of the light .30's, sited to provide interlocking bands of fire, were sector weapons and I Company would leave them in place when it left the area. The added strength in automatic weapons permitted Lieutenant Duerr to throw "a sheet of steel" at the enemy when he attacked.

Three tanks from the regimental tank company with firing positions on the ridge line and on the reverse slopes provided antitank defense from approximately the center of the company front. The tanks were M4's with 76-mm. rifles. Besides the 60-mm. company mortars, the 60-mm. mortars of L Company, the 81-mm. mortars of M Company, 4.2inch mortars of the 27th Infantry Regiment, and the 105-mm. howitzers of the 64th Artillery Battalion could be called upon for direct support.

From one to four double aprons of barbed wire guarded the approaches to I Company's positions, and Duerr placed bands of triple concertina wire in front of and behind the aprons for increased protection. Four combat outposts lay athwart the Chinese approach trails along the company front. Each consisted of four two-man foxholes arranged in a diamond shape with the point toward the north. Concertina, double aprons of barbed wire, mines, and trip flares surrounded the combat outposts, which were manned only at night by 3 relief teams, of 1 noncommissioned officer, 2 riflemen, and 1 automatic rifle crew of 2 men in each outpost. The outposts stayed in place if they were attacked and fought until ordered to pull back.

Because most of the riflemen in the company were inexperienced, they carried M1 rifles rather than carbines. Lieutenant Duerr felt that new men unaccustomed to fire fights often had "a tendency, often a fatal tendency, to fire all their ammunition in the first two or three minutes of a firefight." Since the M1 ammunition clips held fewer cartridges than the carbine clips, they could not be expended so rapidly. Each platoon had two snipers with rifles equipped with telescopic sights. All weapons were test fired daily, and the riflemen stripped and cleaned their weapons every day to make sure they would be ready to meet an enemy attack.

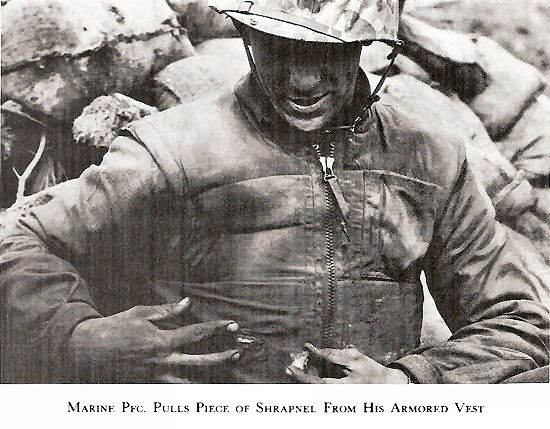

Next to his weapons, the most important item to the infantry soldier was his armored vest. In I Company, the majority preferred the Marine-type vest, which fitted more comfortably and appeared to provide more protection to the wearer. The Marine vest was sleeveless, had nylon padding around the upper chest and shoulders, and had plates of Fiberglas bonded with resin that covered the lower chest, back, and abdomen. The Army vest relied upon layers of basket-weave nylon to take the impact of shell fragments. Neither vest could stop a bullet at close range, but both could help decrease the number of casualties caused by mortar and artillery fire and hand grenade fragments. There was general agreement in I Company that the vests had saved the lives of the men on the lines on many occasions.

The men of I Company also liked the mountain sleeping bag and the insulated rubber combat boot called the "Mickey Mouse." Both afforded excellent protection against the Korean winter weather.

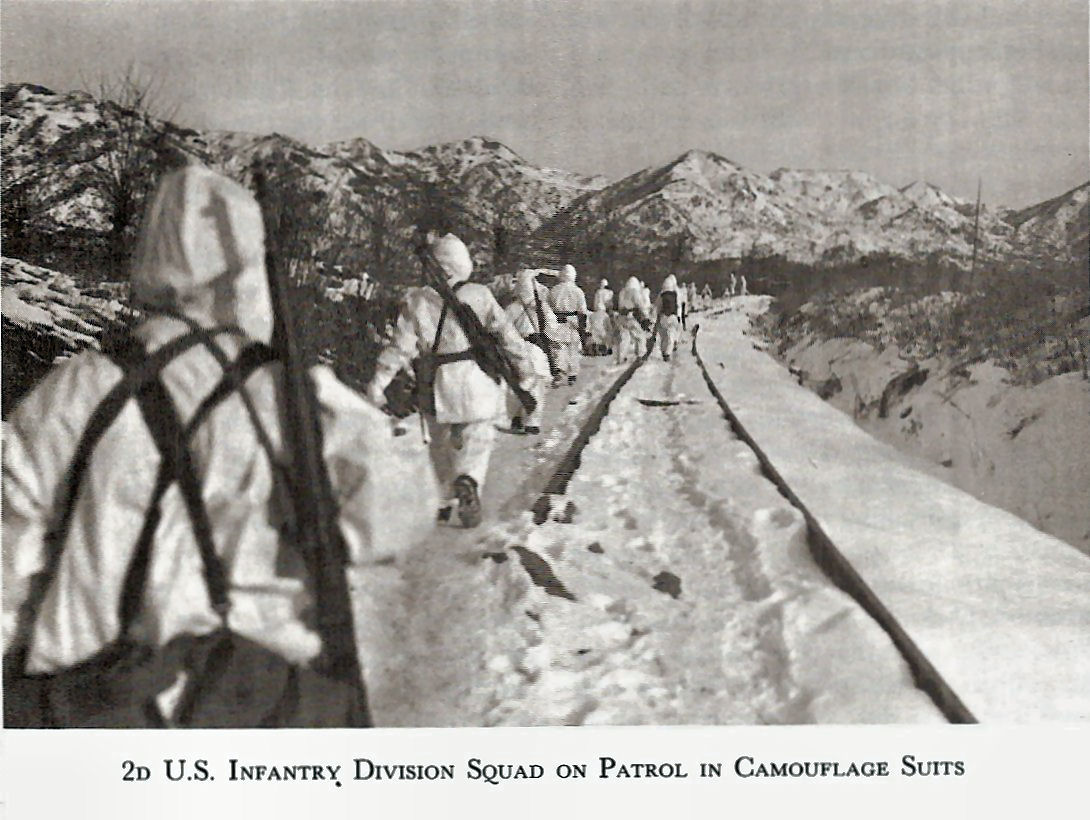

Nightly, the three rifle companies of the 3d Battalion, 35th Infantry, sent out patrols. Col. Autrey J. Maroun, the regimental commander, and his staff planned the patrols one day in advance. They set up the sector, route, objective, mission, strength, time of departure, and equipment to be carried if anything unusual were to be taken along on the patrol. Lt. Col Victor G. Conley, the 3d Battalion commander, frequently briefed the patrol leader, who had been selected by Lieutenant Duerr, on important missions. One company of the battalion furnished the combat patrol on a rotational basis and the other two provided screening patrols. In some cases, the combat patrol probed 1,000 or more yards in front of the main line of resistance while the screening patrols rarely went more than 500 yards.

No soldier went on a patrol until he had been on the line for at least ten days; then, under average conditions he could expect patrol duty once every seven to ten days. The rest of the time he would serve as a guard in the trenches, man a fighting bunker or combat outpost at night, hack trenches in the frozen ground, or erect tactical wire along the slopes. Since there was a 50-percent alert, two men shared one sleeping bag to discourage any shirking of night chores. Eighty percent of the company's work was accomplished at night.

Living conditions depended upon each man's own ingenuity. Since few of the bunkers' living quarters exceeded five feet by eight feet in size, double and triple bunks constructed out of logs, steel pickets, and telephone wire were the norm. Plastic bags used for packing batteries served as windows, straw matting covered the floor, and candles shed their pale light in the bunkers at night. Oil stoves provided heat in most cases, but charcoal and wood stoves sunk into the earth to keep the ground warm were also used.

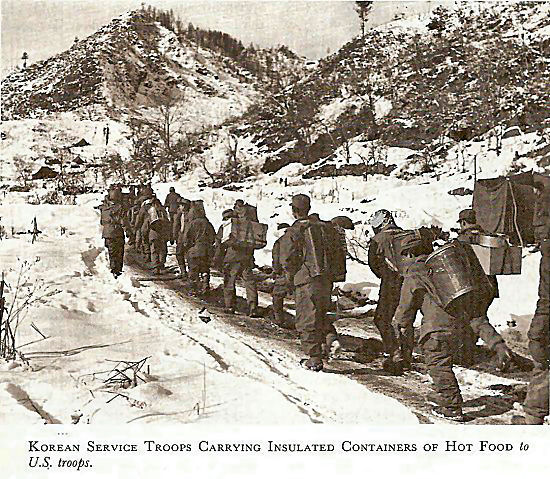

Breakfast and dinner were hot meals served in the two mess areas, while the noon meal consisted of C-rations. The company jeep carried the hot food in marmite cans from the kitchen to the mess area. Since I Company had twenty Korean Service Corps personnel assigned to it, the latter performed all kitchen police (KP) duties.

To insure cleanliness, each man had to shower at least once every five days. By groups the soldiers rode to the battalion shower point and got a complete change of clean clothes after the shower. Every man was required to change his socks daily to guard against trench foot; in addition, the company aidmen inspected the feet of all members of the unit each day. The aidmen also sprayed the bunkers with disinfectant once a month and spread rat poison to control the rodent problem.

Although the biggest morale booster among I Company troops was the rotation system, there were several other programs to provide the men with a change of pace at the local level. A warmup bunker behind the lines served as a day room for reading, writing letters, washing clothes, and getting a haircut. Normally a man could spend several hours in the warm-up bunker every three or four days. Ten men per day left for the Regimental Service Company area to the rear for a 24-hour rest period. During a tour of duty with I Company, every man could generally count on one 5-day rest and recuperation (R and R) leave in Japan being granted. These privileges helped to make the waiting for rotation home a little easier.

When an I Company- soldier approached the magical mark of thirty-six points which qualified him for rotation, he usually stopped going on combat patrols. There were two reasons for this: first, consideration for the soldier whose time was "getting short"; and second, consideration for the other men in the patrol, since the high-point man tended to become cautious and less dependable in combat.

Considering that each company rotated its platoons on the line, that each battalion rotated its companies, and so on right up to the corps level, the chances for an individual to survive during the period of comparative inaction on the battlefield were fairly good. This prospect could not fail to have a favorable effect upon most of the combat troops of the Eighth Army.

The limited nature of the war and the static conditions at the front had an unfavorable side as well. The absence of enemy air operations imparted a false sense of security that might well have been disastrous had the Communists mounted a large-scale air sweep of the battlefield and the supply lines and centers to the rear. Lulled by the lack of enemy air activity over South Korea, the troops tended to become careless in their use of camouflage and in their massing of supplies and equipment at the major ports and depots. Fortunately, the Communists did not exploit this weakness, but the possibility always existed of a swift and bitter lesson in the advantages of dispersion and concealment.

Another mixed blessing was the presence of the Korean Service Corps. In the process of relieving the combat troops of many of the distasteful tasks of soldiering, the KSC had a spoiling and softening effect upon the men in the same fashion that the provision of Italian and Polish displaced persons and prisoners of war had had upon U.S. units in Europe during World War II. At another time there might not be any servants available to perform the unpleasant chores.

A third by-product of the stationary front was the quantity of possessions that the average unit and individual began to collect after a period in the combat zone. Extra equipment and clothing could easily be kept on hand even though they went far beyond the amounts called for in the tables of organization and equipment. As long as mobility was not essential, the surplus might not prove detrimental. But the necessity to shift a unit quickly to meet an enemy threat demonstrated the disadvantages of having too much. During the Triangle Hill battle, one 7th Division artillery battalion took three days to move all its unit and personal impedimenta from the Ch'orwon sector to the Kumhwa area. The loss of mobility indicated that front-line inspections and inventories of unit and individual equipment should have been held frequently to restrain unwarranted accumulations.

X Corps, ROK I and II Corps

Only one important encounter with the enemy in the U.S. X Corps sector had taken place during November. In the Heartbreak Ridge area, on Hill 851, the 2d Battalion, 160th Infantry Regiment, U.S. 40th Division, manned the Eighth Army lines. The terrain north of the 2d Battalion's defensive positions was held by the 14th Regiment, 1st Division, N.K. III Corps. In the opening days of November the North Korean artillery and mortar units devoted increasing attention to the Hill 851 area, and intelligence information gleaned from a deserter and from papers taken from a dead North Korean indicated that the enemy intended to attack the 2d Battalion's positions. (Map VII)

Lt. Col. Robert H. Pell was the commanding officer of the battalion and had deployed his own E and F Companies and attached C and A Companies from west to east along the battalion front. The 143d Field Artillery Battalion, one platoon of 4.2-mm. mortars, H Company's 81-mm. mortars, and one platoon from the 140th AAA Battalion provided direct fire support to the 2d Battalion. G Company and attached B Company, 1st Battalion, were in reinforcing positions south of Hill 851.

On 3 November the enemy artillery and mortar fire became intense. Approximately 4,500 rounds were hurled at the 2d Battalion during the night. At 2030 hours a reinforced battalion from the N.K. 14th Regiment attacked from the north in a general assault along the 2d Battalion front.12 Proceeding along the ridge which ran north and south and up the draws that led to the 2d Battalion's positions, the North Koreans closed and made slight penetrations in the E, F, and C Company sectors. Based on later evidence from POW interrogations, the enemy apparently intended to seize, hold, and reinforce Hill 851, then strike south against Hill 930

The North Korean attack failed as the four frontline companies threw back the enemy assault without calling for reinforcements. Direct fire from the supporting units helped to disrupt and decimate the North Korean ranks. When the enemy broke contact four hours later, he had suffered 140 counted casualties and 7 prisoners of war had fallen into the 2d Battalion's hands. The 160th Regiment had taken 73 casualties, including 19 dead, in the fight.

After a relatively quiet interval of patrols during the rest of November and most of December, the Communists chose Christmas Day to make their next serious attack. On Hill 812, five miles north of the Punchbowl, K Company, 179th Infantry Regiment, U.S. 45th Division, manned the outpost positions on the northern slopes of the hill. Early on Christmas morning the North Korean guns and mortars opened up and sent about 250 rounds on the K Company positions. During the bombardment, a reinforced company from the N.K. 45th Division advanced from Luke the Gook's Castle, a rocky hill nearby, and overran the forward positions defended by K Company. Capt. Andrew J. Gatsis, the company commander, called for artillery and mortar defensive fires.13 Tanks from the 179th Tank Company joined with the artillery and mortar to halt the enemy advance.

Captain Gatsis then sent the second platoon, under 2d Lt. Russell J. McCann, to counterattack. McCann's platoon closed with the North Koreans and pushed them back. In the hand-to-hand fighting in the trenches, Lieutenant McCann was killed. Col. Jefferson J. Irvin, the regimental commander, approved the attachment of A Company to K Company, and L Company was also on hand to reinforce K Company's positions, if necessary. During the early morning hours, the North Koreans sent three platoon-sized attacks and over 2,000 rounds of mixed mortar and artillery fire against the K Company defenders, but failed to dislodge Captain Gatsis and his men. The company suffered 25 casualties in the holiday fighting, including 5 dead, while the enemy incurred an estimated 36 casualties.

On 27 December the newly organized ROK 12th Division began to take over the 45th Division's sector and the relief was completed on 30 December.14

The ROK 12th Division received its baptism of fire some two weeks later when a North Korean battalion launched a surprise attack against outpost positions on Hill 854, seven miles northeast of the Punclibowl. Three enemy companies advanced against elements of the 51st Regiment and made some progress on the left flank. Pushed back by a counterattack, the North Koreans tried once more, then withdrew. Over 19,000 rounds of UNC artillery, mortar, and tank fire were hurled into the enemy zone of attack and the ROK units reported that over 200 casualties were suffered by the North Koreans.15

In early February the North Koreans returned to Hill 812 again. On the night of 2 February, the 37th Regiment of the ROK 12th Division reported enemy troops concentrating for an attack. Intense artillery fire poured into the assembly area, but a North Korean battalion pushed on toward the hill. Within fifty yards of the ROK positions, a savage hand grenade battle broke out and lasted until a reinforcing ROK company turned the tide. The North Koreans used close to 7,000 rounds of mixed explosive ammunition in this heaviest action of the month and suffered over a hundred estimated casualties. They received over twice as many rounds from the UNC artillery.16

During the remainder of February and the following month, operations in X Corps sector were more or less routine. Patrols were sent out regularly, but contacts with the enemy were on a small scale and no sizable attacks took place.17

The North Korean forces had meanwhile been more active on the ROK I Corps front along the east coast of Korea. The ROK main line of resistance positions rested on Anchor Hill (Hill 351) , less then four miles south of Kosong. On 9 November, two North Korean battalions struck Anchor Hill and pushed the ROK 5th Division defenders off the crest. It was only after two counterattacks marked by hard close fighting and backed by intense artillery and mortar support that the ROK troops were able to eject the enemy and restore their positions. At the same time, further to the south, the North Koreans dispatched platoon-sized groups to assault Hills 268 and 345, less than two miles south of Anchor Hill. On the former they won a brief foothold but were driven off on 10 November. Close defensive fires dispersed the enemy attack force as it approached Hill 345. Nothing daunted, the North Koreans hit both hills again on 11 November with a larger force and engaged the ROK troops for an hour and a half before they withdrew.18

The failure of this effort marked the beginning of a period of comparative calm on the ROK I Corps front. Active patrolling and small skirmishes occurred frequently, but the over-all situation was not affected. In early January patrols from the ROK 5th Division located a tunnel entrance and ventilating shaft near Anchor Hill, where the enemy was digging his way close to the ROK positions. After the enemy's work detail entered the tunnel on 7 January, a ROK patrol blew up the entrance and sealed the shaft with explosives. Within a few days the enemy had reopened the entrance, so the South Koreans called for an air strike and closed it once again.19

Little unusual activity marked the ROK I Corps sector until the end of March. The ROK 15th Division completed its organization and training period in late January and moved into the ROK 5th Division's position on the northeastern tip of the battle line.

On 30 March the 13th Regiment of the ROK 11th Division carried out two raids on enemy hill positions just west of the Nam River. The regiment took the crest of Hill 350, which was less than a mile south of Sindae-ri, with the aid of about 6,000 rounds of mortar fire, then withdrew to the main line of resistance at dusk.20

The ROK II Corps had patrolled vigorously during November and December, but operations had remained on a small scale. Its greatest challenge arose in mid-January when an increase in enemy artillery and mortar fire on a platoon outpost on Hill 394, three miles southeast of Kumsong, alerted the ROK 6th Division to the possibility of imminent attack. The commanding general of the division alerted his artillery units and had three tanks move into supporting positions.

On the night of 17 January the enemy guns hurled over 5,000 rounds of mixed artillery and mortar fire at the ROK positions in the vicinity of Hill 394. Close on the heels of the barrage, four Chinese platoons advanced to engage the ROK defenders. When the ROK artillery and tanks opened up on the enemy and threatened to halt the attack, the Chinese sent in two more reinforced platoons. So great was the volume and accuracy of ROK fire that only seven Communist soldiers reached the ROK lines and they were killed or captured in hand-to-hand combat. After regrouping, the enemy tried again with like results. The ROK soldiers estimated that they had killed 1 25 Chinese in this fray as compared to losses of 3 killed and 1 4 wounded for their own side.21 After this brief but bitter action, activity on the corps front settled back into its familiar routine and contacts occurred infrequently and involved very small groups of men.

The U.S. I Corps

Over on the western flank the U.S. I Corps had not encountered a great deal of opposition during the last two months of 1952. U.S. 2d Division outposts on Porkchop defended by the Thailand Battalion were attacked twice in the first part of November, once by a Chinese company and the second time by two companies. On 7 November a heavy artillery and mortar concentration on Porkchop heralded the Chinese advance. After a 45-minute fire fight the enemy broke off and regrouped, then stormed back again and was repulsed. Four days later, the Chinese bombardment of Porkchop announced the second assault. Approaching from the north, east, and southwest, two enemy companies reached the Thailand trenches before they were thrown back. Later that night the Chinese made two further attempts to penetrate the Porkchop positions and then disengaged completely.22

The 1st British Commonwealth Division came in for a bit of excitement on 18 November when a sudden increase in Chinese artillery and mortar fire signaled forthcoming enemy action. After shelling the positions of the 1st Battalion, King's Liverpool Regiment, as a diversion, the Chinese quickly shifted their efforts to a hill known as the Hook. The Hook was part of an east-west ridge four miles northwest of the confluence of the Sami-ch'on and Imjin Rivers and was held by the 1st Battalion of the Black Watch. Forty-five minutes of heavy firing followed; then an enemy company sought to close with the Black Watch. But the Commonwealth forces took cover in nearby tunnels and directed an artillery concentration on the assault troops. As soon as the artillery ceased, the Black Watch seized the initiative, and drove the Chinese off the Hook. While the Communists tried to regroup on adjacent ridges, artillery and tank fire forced them to disperse.

On the following day the Chinese brought up reinforcements and sent two companies against the Hook. Commonwealth tanks and reinforcements moved up and after a hardfought exchange that witnessed hand-to-hand combat, the British forces turned the Communists back. Again the Chinese reorganized and dispatched a company to pierce the Black Watch line. The third try effected a penetration of 100 yards before it was contained. Finally, the 3d Battalion of the Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry mounted a counterattack and in close combat ejected the enemy troops. There were loo counted Chinese dead on the battlefield after the engagement and 85 Commonwealth casualties.23 Evidently convinced that the British intended to hold the Hook, the Chinese made no further serious attempts to seize the hill until the following March, after the U.S. 2d Division had taken over the Commonwealth Division's sector.

The first ten days of December gave little indication that the enemy intended to test the ROK 1st Division's defense in the vicinity of the double horseshoe bend of the Imjin River. On the west bank of the river, as it began its first horseshoe turn, lay a low hill complex known as Nori; Big Nori formed the western half of the ridge and Little Nori the eastern half. (Map 7) The ROK 15th Regiment maintained outposts on these hills and also on Hill Betty, about three-quarters of a mile south of Little Nori, and on Hill 105, approximately a mile southwest of Little Nori. The Chinese controlled outposts on the terrain to the north and west of Nori, but had remained fairly inactive in that sector in early December.

On the 11th, however, two battalions of the 420th Regiment, 140th Division, 47th Army, closely followed Boo rounds of artillery and mortar fire in an attack upon the ROK outposts on Little Nori, Betty, and Hill 105. The main weight fell on Little Nori as two enemy companies sought to dislodge the men of the ROK 15th Infantry. After a bitter 3-hour exchange at close range, the ROK defenders were ordered to pull back to Hill 69, 300 yards to the east of Little Nori. After regrouping, the ROK 15th launched two counterattacks, but the two platoons committed failed to drive the enemy off the heights. The Chinese waited until the attack forces neared their defensive positions, then hurled hand grenades and loosed a withering artillery, mortar, and small arms fire. Later in the morning, however, a small force from the ROK 11th Regiment, which had relieved the 15th Regiment, reoccupied Little Nori without opposition.

In the meantime, the ROK units on Betty had held, but those on Hill 105 had to fall back temporarily. Evidently the Chinese movement against Hill 105 was only a diversion, for the enemy left shortly thereafter and the ROK forces reoccupied the positions without incident.

On the night of the 11th, the Chinese first launched a two-company drive against Little Nori, then increased the attacking force to a battalion, and the ROK's again withdrew to Hill 69. Air support was called in and six B-26's dropped over one hundred 26opound fragmentary bombs on the hill. Twelve battalions of artillery poured a continuous hail of shells on the Chinese, but four counterattacks by the ROK 11th Regiment on 12 December failed. Despite the punishment administered by large and small arms and the mounting toll of losses, the Chinese refused to be budged.

The artillery concentrations went on during the night of 12-13 December and when morning arrived, a battalion from the ROK 11th Regiment moved in with two companies in the attack. Fighting steadily forward, they won their way back to Little Nori, but met with little success in their efforts to clear Big Nori. On the evening of the 13th, the South Koreans dug in and awaited the expected enemy counterattacks. Two Chinese companies vainly attempted to penetrate the ROK positions during the night and as the morning of 14 December dawned, the contest resolved itself into a stalemate.24

Although this encounter lasted but four days, the statistics are quite significant. The entire action on Big and Little Nori took place in an area 300 yards wide and 200 yards deep. During the engagement the UNC artillery fired 120,000 rounds, and the mortar crews over 31,000 while tankmen added over 4,500 go-mm. shells to the deadly concentration. Supporting aircraft flew 39 missions of 177 sorties to bomb and strafe the enemy positions with napalm, high explosives, and rockets. In return the ROK's received over 18,000 rounds of mixed artillery and mortar fire from the Chinese guns. Not counting the aerial contribution, the UNC forces took one round for every eight they hurled at the Communists. It was an excellent example of air, artillery, and tank co-ordination in support of the infantry. As for casualties, the ROK's suffered about 750, including 237 dead, while the estimated total for the enemy ranged between 2,290 and 2,732. According to a deserter from the Chinese 420th Regiment in January, the regiment was removed from the line because of the heavy casualties it took in the battle and placed in reserve.25

Action in the Nori sector settled down to patrols and raids during January. The enemy dispatched two platoon-sized probes during the month and on 23 January the ROK 11th Regiment sent a three-platoon raiding party against Big Nori. Air strikes, artillery, and mortar fire, and fire from twelve supporting tanks enabled the raiders to gain the crest, destroy enemy bunkers, and then withdraw safely.26

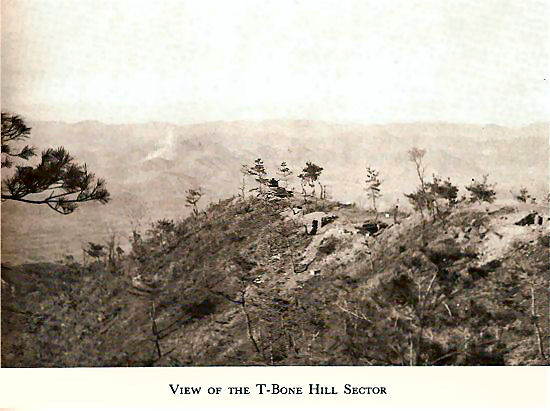

After a 6-week period of comparative quiet, the Chinese chose Christmas Eve to launch an attack upon the outposts of the U.S. 2d Division on T-Bone Hill. (See Map 4.) The southern tip of T-Bone, which contained the outposts of EERIE and ARSENAL, lay approximately two miles northeast of Porkchop Hill. On 23 December, two platoons from B Company, 38th Infantry Regiment, manned ARSENAL, located about 600 yards north of EERIE. On the terrain to the north two battalions of the 338th Regiment, 113th Division, CCF 38th Army, held the enemy lines.

A message intercepted that morning indicated that the Chinese might stage an attack either on the night of the 23d or the morning of the 24th, so all battalions were alerted. Despite the warning, the enemy achieved the element of surprise when the 7th, 8th, and 9th Companies, 338th Regiment, opened their attack about midnight. The Chinese departed from their customary tactic of heavy preparatory artillery and mortar fire before the assault.27 Instead they infiltrated the B Company outposts on ARSENAL, cutting through the barbed wire and successfully bypassing the listening posts. Approaching from several directions, the Chinese reached the communication trenches and closed in hand-to-hand combat with the defenders of B Company. To prevent the 1st Battalion, 38th Regiment, commanded by Lt. Col. Roy I. Brooks, from reinforcing ARSENAL, the enemy placed a blocking force between EERIE and the main line of resistance and sent over 2,000 rounds of artillery and mortar fire against nearby 38th Regiment outposts. Evidently the Chinese hoped to isolate the ARSENAL-EERIE outposts until they could gain possession of the hill complex.

In this they were disappointed, for Col. Archibald W. Stuart, the commander of the 38th Regiment, quickly alerted Lt. Col. George C. Fogle, his 3d Battalion commander, to move his four companies forward to reinforce the 1st Battalion. Two squads from EERIE advanced to reinforce ARSENAL, in the meantime, and a platoon from C Company reinforced EERIE.

The battle in the ARSENAL trenches had also turned against the Chinese attackers. B Company had requested close defensive fires to deter the enemy from reinforcing the infiltrators and then set about to wipe out the Chinese already in the outpost positions. How successful the defensive fires and the stout defense mounted by B Company proved to be was graphically illustrated by the following intercepts of enemy messages during the early morning lours of 24 December.

0026 hours. Send reinforcements quick. There are around 30 enemy coming now-pause-lots of enemy coming now.

0040 hours. How soon will the reinforcements arrive?

Very soon. They are running over. They got plenty of prisoners now, but they can't find a way to get back.

0050 hours. Our reinforcements haven't reached No. 25 yet. They won't be able to get down themselves even without the prisoners.

0052 hours. Can you come down?

No.

Try if situation allows. We don't have a chance without reinforcements.

0120 hours. Where are the reinforcements now? I am sure they will reach your place pretty soon. Now there are too many enemy. We are all surrounded. I don't think our reinforcements can break through and come up either. Our situation is pretty dangerous, besides we have to watch the prisoners. In time of emergency what shall we do with the prisoners?

0130 hours. If it's possible, your people had better just come down yourselves, as to the PW's or wounded, just bring any number you can or leave them there. This is an order. You must come down or we won't contact you anymore.

0132 hours. Send more reinforcements or we won't be able to come back with the PW's.

0217 hours. Our 900 dollars [9th Company] probably has been annihilated. One of the men in the 900 dollars escaped and reported this.

0435 hours. Check how many men we have. I have already checked the 800 dollars [7th Company] has 17 back. 800 dollars [8th Company] has 13 back. 900 dollars unknown.

Two hours later the enemy had gotten back two more men from the 8th Company, but there was no news from the 9th Company. The Chinese battalion had been heavily hit with 11 counted killed in action and estimated casualties of 500 more. The 38th Regiment suffered 47 casualties, including 6 killed in action.

When Brig. Gen. James C. Fry, the 2d Division commander, learned of the high ratio of enemy casualties to those of the 38th Regiment, he commented: "Very nice piece of work." He enjoined his unit commanders to "mention what happens when you stand in your trenches and fight."28

The men of B Company had fought bravely and systematically cleaned out the enemy infiltrators. Yet without the superb defensive fire that had been provided by the artillery, mortar, tank, and AAA units in direct support of the 38th Regiment, the infantrymen might not have fared so well. The enemy had wanted desperately to reinforce his attacking forces on ARSENAL, but had been unable to get them through the curtain of fire laid down by the direct support crews. The success could justly be shared by infantrymen and gun-crew members alike.

On 29 December the U.S. 7th Division completed the relief of the 2d Division in this sector and the Chinese evidently decided to take advantage of the change-over. A reinforced enemy company that night hit an outpost at Chongjamal, two miles southwest of Old Baldy, and forced the defenders to pull back. Since the U.S. artillery units had the co-ordinates of the outpost, they began to zero in on the Communists and the punishment finally forced the Chinese to evacuate the position.29

The 7th Division took part in an experiment in airtank-artillery-infantry co-ordination in late January that produced loud repercussions in the United States. In mid-December a joint ArmyAir Force conference at Seoul had discussed the carrying out of General Clark's direction that a series of airground operations experiments be mounted.30 Three experiments were planned: A. An air strike by 24 fighterbombers with briefing and observation of the target by air force personnel before the operation; B. An air strike by 8 fighter-bombers, without prebriefing, which would be controlled by the tactical air control party at the divisional level; and C. An operation similar to B above, but with 4 fighterbombers.

When Eighth Army G-3 officers approached General Smith of the 7th Division on the matter, he suggested using the air effort in conjunction with a tankinfantry raid to capture prisoners. The task of preparing the operations plan fell upon the 31st Infantry Regiment and the S-3, Capt. Howard H. Cooksey, on 15 January drew up what was to be called Operation SMACK.

The objective selected for the test was called Spud Hill and was an enemy strongpoint on the eastern side of the shank of T-Bone Hill, about 1,300 yards north of EERIE. After the Air Force had launched 125 fighter-bomber sorties and 8-12 radar-controlled light and medium bomber sorties on selected targets in the T-Bone area, the artillery would carry on the bombardment. One field artillery battalion and elements of 6 others with 78 light and 32 medium artillery pieces would fire in direct and general support of the raiding party, from their positions behind the main line of resistance. For the attack force I platoon from the 2d Battalion of the 31st Infantry Regiment and 3 platoons of medium tanks, mounting gomm. guns, were designated. Two additional platoons of infantry, I light tank company, and 6 platoons of medium tanks would act in a supporting role.

During the period 12-20 January, the 57th Field Artillery Battalion, alone in direct support of the 31st Regiment, poured close to I 10,000 rounds of 105mm. fire into the T-Bone complex, seeking to destroy enemy bunkers, mortars, and automatic weapons in preparation for the attack. As D-day-25 Januaryapproached, Air Force officers visited the 7th Division command post and received their briefing and reconnoitered the target area.

Since the experiment promised to be of interest to both air and ground officers, General Barcus and members of his Fifth Air Force staff arrived at the battle locale and were joined by General Smith and Lt. Gen. Paul W. Kendall, the I Corps commander, along with some of his staff. Also present were about a dozen members of the press. To help these visitors understand the schedule and purpose of the exercises, the 7th Division had prepared a combination itinerary, description of the experiment, and a scenario outlining the main events. The cover for this six-page collection of information was in three colors, showing a 7th Division black and red patch superimposed on a map of Korea in blue.31 The choice of a tricolor cover and use of the word "scenario" was unfortunate, as it turned out.

On 24 January the Air Force dropped 136,000 pounds of bombs and 14 napalm tanks on the target complex. The next morning, as the infantry and tankers gathered in the assembly areas, the Air Force began the first of eighteen strikes. Carrying two 1,000-pound bombs each, eight F84 Thunderjets swept over the cross of T-Bone and unloaded their cargo. By midmorning, 24 more Thunderjets, in flights of eight, had bombed enemy positions on T-Bone. Then came a mass strike by 24 Thunderjets, with 48,000 pounds of bombs. This completed experiments A and B. Twenty additional Thunderjets in 2 flights hit the objective before the tanks and infantry began to move out.

Diversionary tank movements and fire to confuse the enemy began as the assault troops made their final preparations. Then the 1 5 supporting tanks from the 73d Tank Battalion (M) crossed the line of departure. While the tanks rumbled forward to their positions, Experiment C was attempted by two flights of four F-84 Thunderjets each. The first flight missed Spud Hill with its bombs and the second flight put on the target only one of the eight napalm tanks that the planes carried. Shortly after the last strike by the Air Force, eight F4U Marine Corsairs attempted to lay a smoke screen in front of the tanks and infantry to conceal their approach, but some released the bombs too soon and others failed to place them where they would shield the attack force.

Once the air phase was completed, the supporting artillery, mortars, AAA, and automatic weapons along the main line of resistance opened fire. As the supporting tanks reached their firing positions close to Spud Hill, they joined in the bombardment of the enemy strongpoints and trenches. To co-ordinate the available firepower, a communications network had been set up between all supporting units, fire direction centers, the 2d Battalion command post, and the infantry Fire Support Co-ordination Center. Major Phillips, the 2d Battalion commander, directed the operation from his command post and had an artillery liaison officer at his side.

For the assault of the hill, Major Phillips had ordered E Company to furnish the platoon and the company commander had chosen his 2d Platoon, under 2d Lt. John R. Arbogast, Jr., for the task. The platoon had rehearsed the operation nine times on similar terrain and knew what it had to do. To increase the possibilities for success, two flamethrower teams had been added to the platoon for the operation.

Since the infantry had to wait until the air strikes were completed, the attack was not set up for a prescribed time, but rather was to begin on Major Phillips' order. Unfortunately, a radio failure caused a fifteen-minute delay in the receipt of the attack order and Arbogast and his men were late in crossing the line of departure. As they moved forward to the base of Spud Hill in personnel carriers, the supporting tanks and artillery continued to pound the objective and enemy positions in the surrounding areas.

Arbogast's platoon dismounted quickly when it reached the foot of the hill and divided into two groups. Two squads began to climb up the northern finger and the remaining two squads took the southern finger of Spud Hill. During this ascent, the supporting weapons, with the exception of the three tank platoons, shifted their fire to targets north of the objective.

Desultory fire from small arms and automatic weapons greeted the 2d Platoon as it headed for the crest. It was not until the squads neared the point where the two fingers met, reuniting the attacking troops, that the Chinese started to react strongly. Then, suddenly, the machine gun fire became intense, driving the men of the 2d Platoon into a defiladed hollow between the two fingers. The depression gave Arbogast's men respite from the chattering machine guns, but exposed them to another danger. Boxed in in a small area, they fell easy prey to the hand grenades that the Chinese lobbed into the hollow from their trenches on the crest of the hill.

As grenade after grenade fell into the midst of the hemmed-in platoon, the casualty list mounted. Lieutenant Arbogast was hit in the arm, but refused to leave. With grenade fragments filling the air, the litter bearers found it difficult to keep up with the growing number of wounded.

In an attempt to break up the grenade attack, the two flame thrower teams were called forward. A rifle bullet instantly killed one of the operators as he worked his way toward the crest. The second operator managed to get off one short burst before the machine malfunctioned. Flames engulfed the Chinese trenches for a few seconds and halted the flow of grenades briefly. After the fire died out, however, the Chinese sent increasing numbers of grenades into the hollow and the list of wounded grew.

Seeing that the assault platoon was pinned down, Major Phillips ordered the 1st Platoon to reinforce Arbogast's remaining troops. The 1st Platoon followed the same route up the fingers and enemy machine guns soon forced it to take cover. Efforts by the supporting tanks to silence the enemy's automatic weapons met with little success since smoke and dust obscured the tankers' view. Every half hour four Thunderjets dropped bombs on the T-Bone complex, but they, too, had little influence upon the fight on Spud Hill.

Lieutenant Arbogast tried to get his men moving out of the trap. But even as he sought to organize a charge, he was again hit by grenade fragments, this time in the face and eye. Although he refused to be evacuated at first, the seriousness of his injuries soon forced him to give in. His platoon sergeant and several of the squad leaders had already been put out of action.

With two platoons now pinned down short of the objective, Major Phillips decided to commit the 3d Platoon to the attack, but the end result proved to be the same. The stream of automatic weapons and rifle fire coupled with the grenades from the enemy trenches halted the advance of the 3d Platoon and inflicted numerous wounds on its members.

When Col. William B. Kern, the regimental commander, learned of the fate of the 3d Platoon, he called off the attack and ordered the men remaining on the approaches to Spud Hill to withdraw. By this time all three platoon leaders had been wounded and the casualty total had reached 77 men.

The expenditures in ammunition for Operation SMACK had also been rather costly. Besides the bombs and napalm dropped the day before the attack, the Air Force had loosed 224,000 pounds of bombs and eight napalm tanks on 25 January. The supporting artillery fired over 12,000 rounds of 105-mm. and 155-mm. and nearly 100,000 rounds of .50-caliber and 40-mm. ammunition. From the tanks came over 2,000 rounds of go-mm. and over 75,000 rounds of lesser caliber. A heavy mortar company added over 4,500 rounds of mortar fire to the attack and the infantry assault force shot over 50,000 rounds of machine gun and small arms ammunition and threw over 650 hand grenades at the enemy. Even if the highest estimate of enemy casualties was accepted, all of this potential death and destruction cost the Chinese fewer than 65 men, while the enemy, using but a fraction of this amount of ordnance, had inflicted greater losses upon the 7th Division force. To top it off, since the infantry had not closed with the enemy, not a prisoner had been taken.

What went wrong? In review, one might say- everything. The air bombardment evidently had little effect upon the enemy in his deep, protected bunkers and caves and the strikes attempted to hit too many targets peripheral to the infantry objective. Secondly, the infantry's late start in setting out for the objective after the strikes allowed the enemy time to prepare for the attack. By confining the assault to a narrow front, as was the case in the earlier Bloody Ridge-Heartbreak Ridge operations, the enemy could concentrate on containing the small attack force. The latter was fairly green and its leadership was impaired early in the fight through the effective enemy use of hand grenades while the platoon was pinned in. In addition the available flamethrowers which might have saved the situation malfunctioned and some of the automatic weapons jammed. The assault platoon had rehearsed the operation many times and felt overrehearsed, while the two supporting platoons that had been thrown in late had not been adequately rehearsed or briefed. All in all, Operation SMACK was a fiasco.

Yet since the entire exercise was on a small scale insofar as the number of infantrymen and tanks engaged was concerned, it might well have been chalked up to experience and quietly passed over, but for a zealous member of the press. Although the correspondent had but recently arrived in Korea and had not been present at the scene of action, the attendance of high-ranking officers of the Air Force and Army at the experiment and the use of the three-color cover and the term "scenario" for the information sheets assumed roles of importance in the story that he wrote. The implication that a show involving needless loss of life had been put on for the visiting brass created a furore in the United States and led to a brief Congressional investigation.32

An official statement by Van Fleet's headquarters and appearances by General Collins before Congressional armed services committees served to put the SMACK operation in proper perspective as a test of methods of coordinating a combined attack on enemy outposts and not as a "gladitorial" exhibition staged in the Hollywood style to entertain visitors.33 Congressional leaders accepted the Army's explanations and the ill-fated SMACK incident was closed. It was an expensive lesson that demonstrated again that firepower in itself, whether dropped from above or hurled from the ground, was not enough to neutralize an enemy well dug in and that the advantage in this limited war lay on the defensive side.

Elsewhere on the U.S. I Corps front, the action was confined chiefly to small raids during January. A platoon from the Marine 7th Regiment on 8 January took Hill 67, which was a mile and a half east of Panmunjom, with the aid of air, artillery, and seven flame-throwing tanks, then withdrew. A week later three platoons from the same regiment hit this hill and another close by for three hours before breaking off the fight. On 24 January two platoons of the Ethiopian Battalion attached to the U.S. 7th Division seized a hill south of Old Baldy after a 45-minute battle and fought off a counterattack. Both the enemy and the Ethiopians built up their forces the following day, as two Chinese companies tried to win back the hill from four platoons of Ethiopians. The latter made a good showing and did not break contact and withdraw until they were ordered to.34

Toward the end of the month, General Clark warned Van Fleet that there were indications the enemy might try to take advantage of the period before the ground thawed to launch an offensive toward Seoul. During the winter the Communists had built up their forces in Korea to an estimated total of 1,071,080 by 1 February and had been stockpiling ammunition and rations at the front. In January three Chinese armies and one North Korean corps had been replaced on the line by fully equipped and combat-trained units and the strength of the remainder of the divisions at the front had been increased from reserve elements. It was, of course, quite conceivable that the Communist preparations were only defensive in nature since considerable publicity had been given to the possibility that the new Republican administration in the United States might change the tenor of the Korean War and go over to the offensive .35

Van Fleet was not worried. He was going ahead with the divisional reliefs scheduled for the closing days of January and told Clark that the Eighth Army was in better condition insofar as reserves were concerned than ever before in the war. He was sure that Eighth Army could handle anything that the enemy could throw at it.36 In his last days as commander of the Eighth Army, Van Fleet remained confident that the force he had helped build up into an efficient and reliable army could meet the Communists head on at any time and emerge victorious. Despite the frustrations of fighting a limited war, the energetic and aggressive old warrior had lost none of his drive or desire to deal the enemy a crippling military blow. . He had frequently shown his impatience at being forced to play a waiting, defensive game, but had never wavered in his efforts to maintain Eighth Army at peak efficiency in case either the United States or the Communists decided to alter the complexion of the conflict. As he left for retirement and home in February 1953, his contributions to the maintenance of his command as one of the better armies fielded by the United States were beyond question.

Notwithstanding Van Fleet's assurances, Clark told General Weyland to have his air reconnaissance planes intensify their observations of Communist ground forces, supplies, and equipment along the PyongyangKaesong route. The Far East commander was concerned over the mounting ability of the enemy to stage an air offensive and ordered his subordinates to take all possible passive air defense measures to absorb hostile air attacks. If trouble developed, Clark wished every precaution possible taken to lessen the blow and he was ready to move the 1st Cavalry Division and 187th Airborne RCT back to Korea in the event of an emergency.37 As Clark pointed out to the JCS in early February, the Communists' recent expansion in men and planes might well be only defensive, but the publicity given UNC ammunition shortages, personnel deficiencies, weakness in reserve divisions, and difficulties in building up NATO strength, coupled with predictions of UNC augmentation and offensive action because of the change in political administration, could influence the enemy to use his offensive strength.38

The growth of Communist air power featured the addition of jet bombers and fighters which gave the enemy a broad air capability. If the Chinese carried out a surprise low-level attack with the MIG's escorting the jet bombers, Clark felt that they might knock out the UNC interceptor bases and gain a respite during which they could repair the North Korean airfields. This, in turn, could lead to a ground offensive, backed by piston fighters, bombers, and ground attack planes. Under the circumstances, Clark asked for permission to attack the Chinese air bases if the security of the UNC forces seemed to be threatened.39

As in the past, the American leaders in Washington were sympathetic but noncommittal. They recognized the potential danger, but told Clark that they wished to be informed of the immediate situation before they gave their authorization.40

Clark's air chief, General Weyland, shared his commander's concern over the Communist air threat, but had no doubt about the ability of the UNC forces to turn the enemy back. "I have no fears," he told Clark on 11 February, "that the enemy could take the Seoul complex if faced with concerted and aggressive counteroperations. In fact, I believe that an attempted air and ground offensive by the Communists can be made a most costly venture for him and would provide opportunity for an outstanding UN victory."41

As February progressed and no larger enemy attacks developed, Clark's anxiety diminished. On 11 February, Lt. Gen. Maxwell D. Taylor took over General Van Fleet's post as Eighth Army commander and began to make his own impression upon his troops.42 He stressed the need for planning and rehearsing patrols; for providing a complete eight-week training program for reserve divisions before they re-entered the line; for moving artillery battalions frequently to maintain their basic mobility; and for better concealment measures for troops on skyline positions. He also decided to drop the designation of "Korea" from the Eighth Army. In the future, the title would simply be Eighth U.S. Army.43

Although the pattern of fighting underwent little change during early February, the enemy reacted strongly to any challenge. On 3 February a tank-infantry force from the 5th Marine Regiment followed air strikes and artillery fire in a raid on Hill 101 and Un'gok, ten miles north of Munsan-ni. The marines destroyed installations and beat off several determined counterattacks until they were ordered to withdraw. Estimate of enemy killed during the engagement ran to about 400 men while the marines lost 15 killed and 55 wounded.44

On 20 February the Chinese sent two companies along the shank of T-Bone Hill to attack Outpost EERIE and ran into a 7th Division ambush patrol. Reinforcements from the 17th Infantry Regiment were rushed forward to bolster the patrol and finally a platoon of tanks moved forward to screen the battlefield and help evacuate the wounded. Although all the members of the patrol were either killed or wounded, they had evidently staved off a battalion-sized assault on ARSENAL and EERIE.45

Across the valley at the lower Alligator's jaw, which was located a mile and a half northeast of EERIE, another Chinese company caught a 7th Division combat patrol and subjected it to heavy fire on 24 February. Before the engagement finished, the entire 2o-man patrol became casualties. The day before, on the 1st Marine Division front, a tankinfantry patrol was surrounded by the enemy at Hill go, two miles east of Panmunjom, and a reinforcing platoon had to be dispatched to help them break through the Chinese circle. Hand-tohand combat ensiled as the marines battled their way back to the main line of resistance. On 25 February a Marine patrol started out to capture prisoners of war and destroy installations on Hill Detroit, a little over a mile southwest of the Hook, and encountered a reinforced enemy company. The marines used flame throwers in the caves and bunkers to root out the Chinese and a bitter 45-minute fight took place before the raiders disengaged.46

The growing Chinese sensitivity to the I Corps raids was the prelude to a shift in the enemy's tactics. As March began, the Chinese went over to the offensive again-on a limited scale, to be sure. Dropping the passive role of the early winter period, the enemy started to take advantage of the prethaw season. As the Chinese sent out larger forces in an effort to regain the initiative, pressure along the I Corps front mounted.

On 1 March, a Communist company struck at the positions of the French Battalion after an intense artillery and mortar preparation. The French were attached to the U.S. 2d Division, now manning the section of the line formerly held by the 1st Commonwealth Division. They met the Chinese attack and beat it off after a brief hand-to-hand encounter. Two days later, the Chinese overran a 38th Regiment outpost on the Hook. On 6 March the scene moved to the ROK 1st Division line where the Chinese launched two fruitless companysized attacks on the outposts of the 11th Regiment. That same evening, a combat patrol from the 31st Infantry Regiment of the U.S- 7th Division intercepted an estimated enemy battalion apparently on the way to attack Porkchop Hill and the surprise contact disrupted the Chinese plans. The Communists gunners dropped 8,000 rounds of artillery and mortar fire on Porkchop during the night, but the enemy infantry made no serious attempt to push on toward the 7th Division's outposts.47

There was brief lull along the front with the advent of the late winter rains. Mud restricted the movements of vehicles but did not deter the enemy from resuming the attack shortly after the middle of March. Hill 355, located about three and a half miles southwest of the Nori Hill complex, was also known as Little Gibraltar. Defended by elements of the U.S. 9th Infantry Regiment, 2d Division, Hill 355 received a battalion-sized attack on 17 March. The enemy breached the wire entanglements and pushed through the mine fields into the trenches of the 9th Infantry Regiment. One platoon's position was overrun but the remaining platoons held firm in their blocking positions until reinforcements arrived. As the Chinese began to disengage, 2d Division artillery fire interdicted their route of withdrawal. The action cost the 9th slightly over 100 casualties, but enemy losses were estimated at over 400 men.48

The 2d Division came in for a bit more action four days later when two enemy companies fell on a patrol near the Hook. While the patrol tenaciously fought off the Chinese attackers, artillery and mortar fire were called in and reinforcements rushed up. The Chinese pulled back the next morning.49

On 20 March the 7th Division had indications that the enemy contemplated an attack in the Old Baldy-Porkchop area. The increase in artillery and mortar rounds on the division's positions on these long-contested hills usually signified a Communist offensive move, and the capture of two deserters in the sector strengthened the belief that action would soon be fortlicoming.50

The Old Baldy-Porkchop area was held by the 31st Infantry Regiment, commanded by Colonel Kern, and its attached Colombian Battalion. Colonel Kern had deployed his 2d Battalion on the left, the Colombian Battalion in the center, which included Old Baldy, and the 3d Battalion on the right in the Porkchop Hill sector. One rifle company from the 1st Battalion manned blocking positions behind each of the three frontline battalions.51

Elements of two Chinese armies faced the 7th Division. The 141st Division, CCF 47th Army, manned the enemy positions opposite Old Baldy and to the west and the 67th Divisions, CCF 23d Army, defended the terrain from the Porkchop Hill area to the east.

On the evening of 23 March the Chinese staged a double-barreled attack on both Old Baldy and Porkchop. A mixed battalion from the 423d Regiment,. 141st Division, attacked Old Baldy and caught the Colombian Battalion in the middle of relieving the company outpost on the hill. The Chinese closely followed an intense artillery and mortar concentration upon Lt. Col. Alberto Ruiz-Novoa's troops and fought their way into the trenches. To reinforce the Colombians, Colonel Kern placed B Company, 31st Regiment, under Colonel Ruiz' operational control. 1st Lt. Jack M. Patteson, B Company commander, led his men toward Old Baldy at 213o hours, approaching from Westview, the next hill to the southeast. As B Company drew near the outpost, the Chinese first called in intense artillery and mortar fire along the approach routes and then took Patteson's men under fire with small arms, automatic weapons, and hand grenades. B Company slowly made its way into the first bunkers on Old Baldy at 0200 hours and began to clear them out one by one. As the company came up against the main strength of the Chinese on Old Baldy, however, progress lessened and then ground to a halt.

In the 3d Battalion sector on Porkchop Hill, Lt. Col. John N. Davis' L Company had been attacked by two companies from the 201st Regiment., 67th Division. As in the Old Baldy assault, the Chinese had laid down heavy mortar and artillery concentrations on the I. Company positions before they advanced. 1st Lt. Forrest Crittenden, the company commander, and his men fought until their ammunition began to run low, then had to pull back from the crest of the hill and await resupply and reinforcement. Proximity fuze fire was laid directly on Porkchop while ammunition was brought forward and A Company, under 1st Lt. Gerald Morse, advanced to the aid of L Company. Elements of I Company were ordered to secure Hill Zoo, a mile southeast of Porkchop, which had also been reported as under attack.

Colonel Davis had to wait until the early morning hours of 24 March before he could launch a counterattack against Porkchop. Lieutenant Morse's company, en route to join L company, was pinned down for two hours by proximity fuze fire. Attacking abreast with A Company on the right, the two companies met only light resistance from the few Chinese left on the crest. They reported that Porkchop was a shambles with many of the bunkers aflame and many dead and wounded. Colonel Davis dispatched the ammunition and pioneer platoon to repair the damage and sent aidmen and litter bearers to clear the dead and wounded from the hill.

In the meantime, Maj. Gen. Arthur G. Trudeau, who had just assumed command of the 7th Division, had arrived at the 31st Regiment's command post and had taken charge. He ordered the 1st Battalion, 32d Regiment, under Lt. Col. George Juskalian, to move forward and placed it under the operational control of the 31st Regiment. The 1st Battalion with B Company, 73d Tank Battalion, in support, would carry out a counterattack to regain Old Baldy. The tanks would fire from positions in the valley to the northeast of the hill.

B Company, 32d Regiment, under 1st Lt. Willard E. Smith, led the 1st Battalion's attack from the southwest on the morning of 24 March. Two platoons from the 73d Tank Battalion and one platoon of the 31st Tank Company supported the assault. The Chinese met the assault with artillery and mortar fire as B Company approached and then opened up with small arms and automatic weapons, inflicting heavy casualties on Lieutenant Smith's men. The 1st Battalion's assault stalled on the southwest finger of Old Baldy.

Colonel Juskalian reorganized his forces and sent B Company and A Company, under 1st Lt. Jack L. Conn, in a second attack during the afternoon of the 24th. The two companies reached Lieutenant Patteson's B Company, 31st Regiment, positions and passed through them. By nightfall they had won back one quarter of Old Baldy, but were forced by enemy resistance to dig in and hold. Lieutenant Patteson suffered a broken jaw during the fighting and had to be evacuated.

At 0430 hours on 25 March, Colonel Juskalian sent C Company, under 1st Lt. Robert C. Gutner, around the right flank to attack up the northeast finger of Old Baldy. Again the Chinese used their individual and crew-served weapons effectively and reinforced their units on Old Baldy to halt the 1st Battalion attack. By 0930 Juskalian reported that B and A Companies were one-third the way up the left finger, halted by small arms and hand grenades. C Company was "pretty well shot up" and had to be withdrawn and reorganized. Some members of the company were still pinned down on the right flank of Baldy and could not get out. Colonel Juskalian called for tank support to knock out the Chinese bunkers being used to pin down the 30 to 40 C Company men left on the hill.

Despite the tank support, the 1st Battalion's situation had not improved by 1315 hours. Colonel Juskalian's three rifle companies were clinging to their positions, but A Company had only 2 officers and 14 men; B Company and C Company had 2 officers and 40 men between them. The colonel asked for smoke and medical aid so that he could evacuate his casualties.

With the 1st Battalion's effective strength reduced to less than sixty men, Colonel Kern ordered Juskalian to withdraw his men from Old Baldy during the night of 25-26 March. Air Force, Navy, and Marine fighters and bombers mounted air strikes against nearby hills, strongpoints, and supply routes during the night and then hit Old Baldy the next morning after the 1st Battalion had cleared the hill. From reports made later by Colombians who had hidden in bunkers during the Chinese domination of the heights, it appeared that the enemy troops left Old Baldy when the air strikes came, and this, incidentally, had enabled the Colombians to make their way back to the UNC lines on 16 March.

General Kendall, I Corps commander, ordered another attack to regain Old Baldy to be scheduled for either 27 or 28 March after rehearsals had been held. To carry out the assault, General Trudeau selected the 2d Battalion, 32d Infantry Regiment. The battalion held two rehearsals on terrain similar to Old Baldy in the closing days of March and was prepared to execute the attack. On 30 March, however, General Taylor, the Eighth Army commander, arrived at General Trudeau's headquarters for a conference. After considering the psychological, tactical, and doubtlessly the casualty aspects of the planned operation, General Taylor decided that Old Baldy was not essential to the defense of the sector and that consequently no attack would be carried out.

The two days of fighting for Old Baldy and Porkchop had been costly for the 7th Division. Casualties had run over 300 dead, wounded, and missing in action. Although Chinese losses were estimated at between Goo to Boo men, the enemy had committed his troops freely to maintain possession of Old Baldy. The Chinese willingness to expend their manpower resources offered a clear contrast to the UNC reluctance to risk lives for tactical objectives of questionable value at this stage of the war.

On the 1st Marine Division front the Chinese had also accelerated the tempo. An outpost of the Korean Marine regiment was overrun by two enemy platoons on 18 March and the following day the Chinese threw two company attacks against 5th Marine Regiment ouposts. The latter were beaten off and the marines quickly mounted a counterblowa raid into the enemy's positions. This, in turn, elicited retaliation from the Chinese. On the night of 22 March they sent two companies supported by 1,800 rounds of artillery and mortar against the 1st Marine Regiment's outposts and main line of resistance positions at Hill Hedy and Bunker Hill, four miles east of Panmunjom. Hand-to-hand combat and a brisk fire fight ensued before the Chinese began to disengage. During the encounter a UNC flare plane and searchlights lit up the battlefield and enabled the marines to spot the enemy's movement.52

After a series of diversionary squad attacks on 1st Marine Regiment outposts, the 358th Regiment, 120th Division, CCF 40th Army, launched an assault upon combat outposts of the 5th Marine Regiment, 10 miles northeast of Panmunjom and between 2 to 3 miles southwest of the Hook. Outpost VEGAS was on Hill 157; Outpost RENO was on Hill 148, less than half a mile to the west; and Outpost CARSON was on an unnumbered hill 800 yards south of RENO. (Map 8) Prisoners of war and other intelligence sources later indicated that the mission of the 358th was to seize and hold the three outposts before an expected UNC spring offensive could get under way. On 26 March, the Chinese overran VEGAS and RENO after heavy, close fighting. The marines fell back and hastily prepared blocking positions between the lost positions and the main line of resistance. Despite the arrival of reinforcements during the night, efforts to rewin VEGAS and RENO failed because of intense enemy artillery, mortar, and small arms fire. A battalion from the 7th Marine Regiment was placed under the operational control of the 5th Regiment on 27 March, but even with the additional troops, the counterattacks made little progress. As the day wore on, 3 light battalions, 2 medium battalions, 2 8-inch batteries, 1 4.5-inch rocket battery, 2 companies Of 4.2-inch mortars, and 1 battalion of 25-pounders pummeled the enemy positions, and close air support sought to destroy Chinese strongpoints. Over 100,000 artillery rounds, 54,000 mortar shells, 7,000 rounds of go-mm. tank ammunition, and 426 tons of explosives were directed at the Communists during the fight, while the Chinese sent back about 45,000 at the marines. The decision was made not to recapture RENO for the time being and the Marine units, increasing the attacking force to the infantry strength of two battalions, concentrated on VEGAS. Not until the afternoon of 28 March were the marines able to battle their way back to the top, for the Chinese fire was heavy and deadly.