History  On Line

On Line

The return of sporadic activity on the battlefield in November 1952 and the suspension of other than liaison officer's meetings at Panmunjom forecasted a long, uneventful winter. With raids, patrols, and small-unit actions characterizing operations at the front and with bickering over incidents and infractions of the neutrality of the conference area highlighting the contacts between the negotiators, the problems of limited war continued to receive a considerable share of attention during the winter of 1g5253- In Washington and in the Far East the accent remained on conserving and protecting the most precious commitment of the United States to the war-its manpower. Since military victory was no longer at stake, there seemed to be no reason why American lives should be expended needlessly nor for the burden of fighting to be carried on by the old hands. Under static conditions along the battle lines, more ROK troops could be trained and utilized and units could be rotated more frequently. This would allow U.S. forces to be placed in reserve more often and decrease the number of U.S. casualties. The United States could not end the Korean War nor could it withdraw its troops from the peninsula, but it could trim its losses and equalize the risks that each soldier would have to take.

The Turning Coin

Paradoxical though it may seem, rotation was both the main strength and the chief weakness of the Eighth Army in late 1952. As a bolster to morale, rotation played a vital and necessary role in sustaining the ground forces through the depressing and frustrating conditions created by a deadlocked battle situation. By rotating units in and out of the lines at regular intervals, the monotony of routine patrolling and defensive warfare was broken and a change of pace provided. But even more important was the point system that promised a quick return home to the individual as soon as he had served his time at the front.

Before September 1951, a soldier in Korea had to have a minimum of 6 months in a combat division or 12 months in a support unit to be eligible for rotation. New criteria were drawn up in August establishing the point system. For each month in the close combat zone, a soldier received four points. For service in the rear areas two points were earned, and duty in the rest of the FEC merited one point. In September the requirements were 55 constructive months service (CMS) for officers and 43 for enlisted men.1

As Army strength increased in the fall of 1951 the criteria were lowered to 40 CMS for officers and 36 for enlisted men. The officer standards were raised to 45 CMS in December to cope with an expected shortage of officer replacements scheduled for early 1952.2

March 1952 witnessed an overhauling of the rotation system. Effective 1 April, four points were still awarded for a month in the close combat zone, but only three were given to the troops in the divisional reserve, now called the intermediate combat zone. By June requirements stood at 37 CMS for officers and 36 CMS for enlisted men.3 Generally, slightly less than a year in Korea in a combat division would suffice to put a man on the rotation list and it was small wonder that the point score became the chief topic of conversation among the combat troops.4 There could be no doubt of the value of this bright side of the coin in maintaining the fighting spirit of the Eighth Army during the last year of the war.

But the reverse side disclosed some of the disadvantages in adhering to the practice rigidly. To supply the Far East Command with the 20,000 to 30,000 replacements a month that were necessary to meet rotational demands imposed a severe strain on the Army's manpower resources. As General Hull told Clark in early October, drastic levies on the zone of interior units and installations were going to be necessary to meet the FEC quotas during the coming months. Personnel shortages in the European Command, he went on, had already resulted and overseas tours in all other theaters had been extended six months.5 To keep the point total at 36 for the combat zone during the winter, Clark had to transfer combat troops from Japan and Okinawa to the Eighth Army and to increase the point requirements for the rear areas, first to 38, and later, to 40 points.6

To Clark's request for additional replacements to cover the rotational needs, General Collins replied in December that the Army's ability to furnish replacements was determined by the budget, Army strength ceilings, and by draft calls. The point system, he continued, was devised to establish priority of individuals for rotation and not to set up the rate at which the Army was supposed to supply replacements. Collins, however, was able to offer some comfort, for he informed Clark that the shipments of replacements in January and February would be well over 30,000 and this would permit some of the November and December deficits to be made up.7

At the front, rotation also had an adverse effect upon combat efficiency. By October 1952, most of the junior officers with World War II experience had returned home as their tours expired and their replacements usually had little or no acquaintance with the battlefield. Many of the troops sent over from the United States lacked field training and had to learn the hard way under combat conditions. By the time the new men became proficient soldiers, they had amassed enough points to qualify them for rotation and the process had to start all over again. Proficiency standards were extremely difficult to maintain and the artillery and the technical services were especially hard hit. General Van Fleet complained that the artillery had lost the ability to shoot quickly and accurately and blamed this on the rotation program that had stripped the artillery units of their veteran gunners.8

There were other unfortunate byproducts as well. In a defensive war such as in Korea in 1952, strong fortifications in depth, with carefully laid out fire patterns for supporting weapons, wellplanned mine fields, and barbed wire entanglements to prevent or delay enemy access to strongpoints or outposts were required. The enemy had developed a high degree of skill in establishing his defensive lines and in providing for their protection. In many instances, enemy units defending the forward areas had remained in the same sectors for long periods and become thoroughly familiar with the terrain. Spurred by the knowledge that they would stay in position for some time, they took every possible step to increase the strength of their defenses.

For the UNC troops, the opposite was often true. Since they did not usually man a given sector of the front for any considerable length of time, the tendency was to lay as few mines and as little barbed wire as possible so that the patrols would not have to worry about these hazards. Terrain familiarization was difficult as the outfits constantly shifted in and out of the line.

The enemy also used the terrain much more adeptly. While UNC positions were often located on the crest of hills and ridges or on the forward slopes, where they were more exposed to enemy fire, the enemy used the reverse of slopes for his sleeping and supply bunkers and dug tunnels deep into the hills. When the enemy built his trenches, they were angled and parapeted with raised firing positions; the UNC trenches, on the other hand, too frequently were deep, straight, and difficult to fire from. All too often enemy soldiers could infiltrate and sweep a long straight trench with automatic weapons fire.9 The difference between the enemy and UNC attitude toward defense during this period was similar to that between a homeowner and an overnight guest at a hotel. The enemy became well-acquainted with the neighborhood and took every precaution to protect his property, while the UNC forces adopted the short-term, casual approach of the transient.

Facets of the Artillery War

With rotation as the carrot dangling before his eyes, the individual soldier's main concern was to stay alive until his year of combat service expired. Neither officers nor enlisted men were particularly interested in taking undue chances under these conditions and an air of caution arose. As the reluctance to jeopardize lives grew, the effort to substitute firepower for manpower increased. In October and November, UNC gunners fired eight rounds of artillery and four rounds of mortar fire for every enemy round received. By December, although the mortar ratio dipped to three to one, the preponderance in artillery rounds favored the UNC by nineteen to one.10 The attempt to bury the enemy under tons of explosive hardware generated some interesting experiments.

General Van Fleet was quite concerned over the Eighth Army's use of artillery during the fall of 1952. After conferring with his corps commanders in September, he decided to alter the ratio of 155-mm. guns to 8-inch howitzers. The Eighth Army had forty-four 8-inch howitzers and twenty-eight 155-mm. guns in September and was in the process of converting a battalion of 155-mm. guns to 8-inch howitzers. Van Fleet halted this conversion and ordered the conversion of a 105-mm. howitzer battalion to 8-inch howitzers instead. When the change-over was completed, the Eighth Army would have forty-eight 8-inch howitzers and thirty-six 155-mm. guns. Van Fleet believed that this ratio would provide his army with a better balance in heavy artillery and allow it to get maximum benefit from its superior firepower.11

Once he had reorganized the heavy artillery, Van Fleet determined to try out his plan to concentrate heavy firepower against the enemy's artillery. Choosing the Triangle HillSniper Ridge area in the U.S. IX Corps sector as the locale for the test, Van Fleet attached the 1st Observation Battalion and major elements of two 8-inch howitzer and two 155-mm. gun battalions from the U.S. I and X Corps to the IX Corps artillery. During the long and difficult struggle for control of this hill complex, Van Fleet wrote to Clark, each time that the UNC forces had gained the top, intense artillery and mortar fire had made retention of the crest too expensive. When the enemy forces had moved onto the heights, the UNC artillery had forced them to withdraw. The only way to break this sequence, Van Fleet went on, was to destroy the enemy artillery. Then, the ROK 2d Division could seize and hold on to the hardcontested hill mass.12

Clark was willing to permit Van Fleet's counterbattery program to proceed and to countenance the extra expenditure of ammunition for a five-day period, but he did not want the ROK 2d Division to renew the battle for Triangle until he was sure the results would be commensurate with the risks. If excessive casualties or abnormal ammunition outlays were going to be required to keep Triangle, Clark was opposed to the move.13

Using aerial photography and sound, flash and radar plots, supplemented by shelling reports, the IX Corps artillery staff compiled a target list of enemy weapon locations. On 3 November the experiment began as the greater part of three 8-inch howitzer and three 155-mm, gun battalions fired single guns and salvos at the Communist gun positions. During the next week the heavy artillery shot close to 20,000 rounds in an effort to eliminate the enemy's artillery in the vicinity of Sniper Ridge and Triangle Hill. But the success was only limited. Artillery observers estimated that it took approximately 5o rounds of accurate fire to achieve destruction of an enemy artillery piece because of the Communist's skillful use of caves, tunnels, and heavy overhead protection. During the test period over 25o enemy gun emplacements were damaged or destroyed, but only 39 artillery and 19 antiaircraft pieces were put out of action. The Communist artillery was not silenced and the battle for the hills continued.14

General Clark was not averse to the continuance of a counterbattery program, but he told Van Fleet on 10 November that it would have to be carried on within the normal ammunition allocations assigned to the Eighth Army-at least, until the over-all supply of heavy artillery shells increased.15

Better success attended a second experiment conducted in September and October on the IX Corps' front. The Fifth Air Force commander, General Barcus, requested a flak-suppression effort by Eighth Army artillery units in conjunction with close support strikes by his fighter-bombers. He believed that the use of artillery against enemy antiaircraft artillery weapons before and during the strikes would help cut down Fifth Air Force plane losses to AAA fire. Van Fleet approved a thirty-day test period that began on 25 September. As the fighter-bombers approached the target in the IX Corps sector, the artillery fired proximity fuze shells at the known enemy AAA positions in the area. When the planes closed on the target, the artillery switched to quick-fuze ammunition and continued to fire until the air attack was over. At the conclusion of the experiment on 25 October the Fifth Air Force reported only 1 plane had been lost and 13 had been damaged by enemy antiaircraft fire during the test. A total of 1,816 sorties had been flown and, according to statistics based on previous experience, the losses should have been between 4 and 5 planes destroyed and about 64 damaged. No Fifth Air Force plane had been hit by IX Corps artillery fire during the test. In view of the favorable outcome of the experiment under static ground front conditions, Barcus and Van Fleet instructed their units to make the flaksuppression program standard operating procedure in the future.16

The heavy expenditure of ammunition during the October fighting stimulated a suggestion from Under Secretary of the Army Johnson in the latter part of the month. Impressed by the magnitude of the task of providing adequate 105-mm. and 155-mm. howitzer ammunition for the Eighth Army, Johnson requested General Collins to investigate the feasibility of substituting mortar fire for artillery fire whenever possible. Not only were mortar shells easier to produce and transport, Johnson pointed out, but, he claimed, they also were causing the bulk of the casualties in Korea.17

When Collins passed Johnson's proposal on to the Army Field Forces, they made a quick rebuttal. While granting that two more 81-mm. mortars might profitably be added to each infantry battalion, they stated that both artillery and mortars were designed for particular missions. To use mortars, which were meant for close-in support, to replace artillery, which handled the longerrange tasks, would result in an over-all loss of firepower and battlefield effectiveness. The Field Forces staff doubted that the mortars were producing more casualties than artillery fire, for the statements of prisoners of war indicated just the opposite.18

The Under Secretary's concern over the slow progress of ammunition production was reflected in Secretary of Defense Lovett's message to Clark on 21 November. Noting that the problem had been a continuing one for two years despite large appropriations and attempts to expedite the program, Mr. Lovett informed Clark that he would use all his powers to insure that the shortages did not affect the U.S. forces in combat. He had already ordered a maximum effort to move the necessary stocks to meet FEC needs, including diversion of shipments for other theaters if it proved necessary. To help him correct deficiencies in the United States, Lovett asked Clark to send a complete appraisal of the UNC ammunition situation and its effects.19

In his reply two days later, Clark maintained that the currently authorized ninety-day level of supply for the FEC, at the Department of the Army approved day-of-supply rates for ammunition, was quite adequate.20 The trouble, Clark went on, was that many of the items were below the ninety-day level and that the shipments scheduled for the remainder of the year would not make up the deficits. Since a high rate of artillery fire resulted in lower friendly casualties, he deplored the need to reduce the allocations of 155-mm. howitzer ammunition from 15 to 9.4 rounds per day. The necessity to watch and hoard ammunition had also curtailed the ability of his command to retain the initiative by launching limited objective attacks, Clark continued, and worse than that, made the U.N. Command particularly vulnerable to critical shortages in the event of a general offensive by the Communists. Under the circumstances, he concluded, the only prudent solution was to increase ammunition production as soon as possible to the point where the FEC could be supported at the authorized Department of the Army rate.21

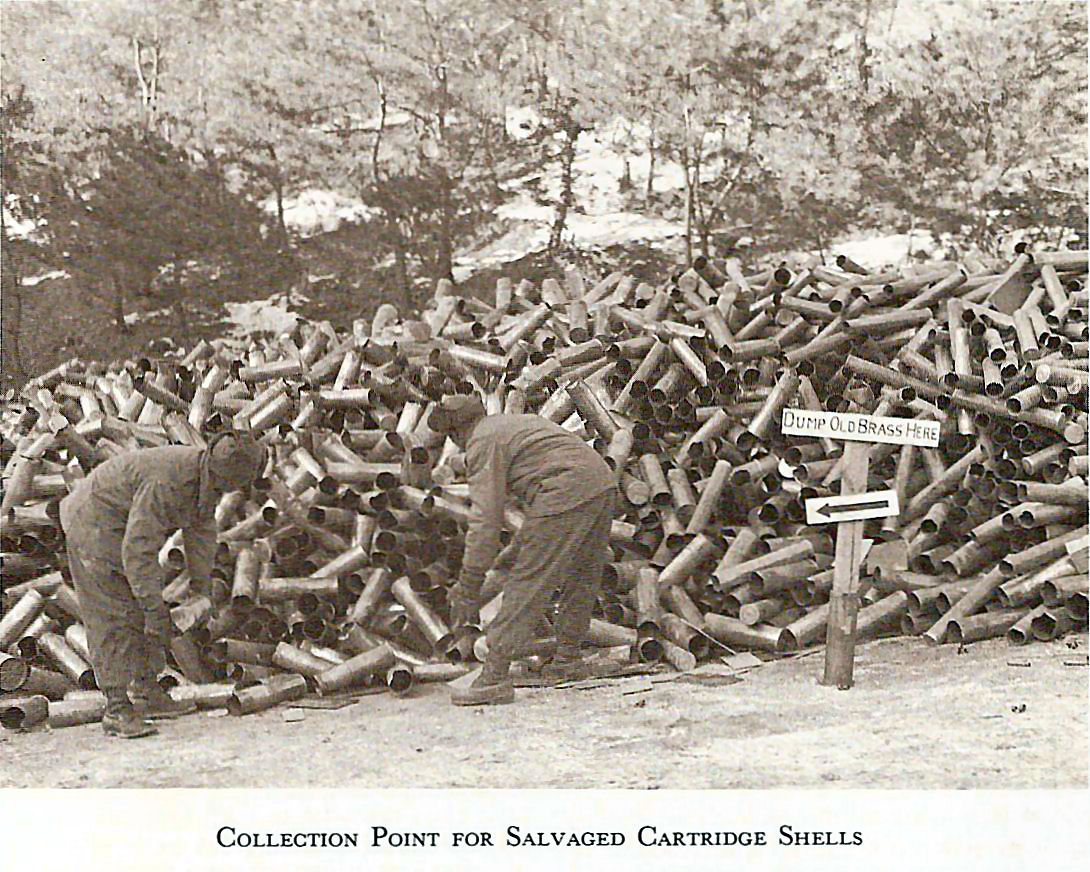

Secretary Lovett promised Clark that the Army would deal with the shortages in ammunition as though the United States were under full production mobilization and that overriding priorities would be granted as needed. One way in which the FEC could help, Mr. Lovett said, would be in returning brass cartridge cases from expended 105-mm. rounds, since this had become a chokepoint in production. Clark immediately asked Van Fleet to aim as close as possible at a 100-percent return of reusable cartridge cases. "While we are still a long ways from being 'out of the woods,'" he told Van Fleet, "I am convinced that our repeated requests for increased supply have finally struck home and that the ammunition supply road ahead will be considerably smoother."22 As the appropriations voted in 1951 for ammunition production expansion finally began to bear fruit in late 1952 and early 1953, the prospects for some relief in the ammunition situation would become much brighter.

In the meantime, the Far East Command and Eighth Army resorted to substitutions to tide themselves over the period of shortages. When the supply of 81-mm. mortar shells became low in January 1953, the Eighth Army units on the line were directed to fire 4.2-inch mortars or to use artillery fire until theater stocks could be replenished.23 To lessen the drain on 155-mm. howitzer ammunition, Clark again sought to convert two of his battalions to 240mm battalions, since there supposedly was sufficient ammunition of this caliber available to sustain two battalions at a rate of fifteen rounds per day. The Department of the Army informed him that equipment and spare parts would arrive in March.24

As the ammunition situation began to improve in early 1953, General Van Fleet returned to the United States to retire. In March and April he appeared several times before Congressional committees for questioning on conditions in Korea. His statements that he had been handicapped during his twentytwo months of command by shortages of ammunition brought the subject out into the open and the Army had to defend publicly its handling of the problem.25

General Collins quickly asked Clark to prepare a statement and on 16 March the Far East commander complied. His assessment of the situation was as follows:

There has been no shortage of small arms ammunition in the theater; stocks of other ammunition as indicated below have been less than they should have been. However, such shortages were mostly in theater stocks and the pipeline and not in forward area combat units. As far as I have been able to determine Eighth Army has never been 'out' of ammunition nor denied authority to shoot ammunition in adequate quantities when required by the tactical situation. Insofar as can be determined, no unit in Korea was refused ammunition for an essential mission.

While Eighth Army was never 'out' of ammunition the shortage limited the combat potential of theater forces. The continued increase in enemy artillery activity with a corresponding increase in friendly casualties required an increase in Eighth Army's counterbattery effort which included the employment of the Corps and Division artillery 155mm Howitzer material and therefore necessitated the expenditure of a critical type of artillery ammunition. In addition, the attack of targets characteristically dug-in at considerable depths required increased expenditures to accomplish their neutralization or destruction. With the knowledge of shortages of critical types of ammunition and their limited production, the amount of ammunition available for day to day operation was necessarily restricted and care was taken to hold down expenditure whenever possible without denying their use when necessary. Had the enemy launched and sustained an all-out offensive during the periods of ammunition shortage, theater stocks would have been reduced dangerously low since this type of operation always results in the expenditure of 3 or 4 times the DA day of supply of ammunition and therefore would have placed us in an unfavorable position in our capability of striking back hard at the most opportune time and place.

He listed the types that had been in short supply at various times and then went on to state that he considered the present levels of ammunition in the theater to be adequate for maintaining current operations and to counter a general Communist offensive if it should materialize, provided "on-hand assets are maintained at the 90-day level."26

The complexities of the ammunition story made the accuracy of the shortage charges extremely difficult to evaluate. But it was doubtful whether more ammunition in the critical categories would have substantially influenced the battle situation in the last two years of the war, for the restrictions on offensive operations were not dependent upon the ammunition supply, but rather upon the political and military objectives of the United States and its U.N. allies at the time. As long as they preferred to settle the war at the conference table and to delimit the Korean commitment, even full stocks of ammunition could have made no real difference in the outcome. The Communist disregard for the loss of lives involved in protracting the war argued that a few thousand more casualties alone would not have impelled them more quickly toward a settlement of the dispute.

The Bulwark Grows

As already related, one way in which the United States could limit the commitment in Korea was by building up the ROK fighting forces. Shortly after President Truman approved the expansion of the ROK Army to 12 divisions in late October, the ROK I2th and 15th Divisions were activated, along with 6 separate regiments. The Eighth Army estimated that the 12th Division and 3 separate regiments would be operationally ready by the end of December and the 15th Division and the other 3 regiments would be prepared for action a month later.27

Thus as early as November, the ROK ground forces had a strength ceiling of 463,000 men.28 But a twelve-division army was only a stopgap measure, in Clark's opinion, and he submitted a plan and schedule on 1 November for augmenting the total to 20 divisions by August 1953. The number of ROK Army Corps would be increased from 2 to 6 to handle the additional divisions. With a 16-week training period set up for the new divisions, the last one activated would be ready for combat before the close of 1953. As the ROK units were organized, equipped, and trained, Clark informed Collins, 1 U.S. or other U.N. division could be placed in reserve for each 2 new divisions prepared. By May 1953, he could begin to release the U.S. divisions- one at a time- for employment elsewhere. If all went well, up to 4 U.S. divisions and 2 corps headquarters could be redeployed by mid-1954.

ROK Army expansion, Clark cautioned, also had its negative side. The Military Advisory Group would have to be enlarged to carry the increased load and over five hundred officers and enlisted men would have to come from outside the theater. If U.S. forces were withdrawn from the line and eventually from Korea, pressure from other UNC countries to decrease their commitments could also be expected. And as ROK troops began to assume more responsibility for manning the front lines, the United States would have to turn over more and more materiel and equipment to them and this could never be recovered regardless of the outcome of the war. Much of this would come from the FEC's strategic reserve and would affect the growth of the Japanese defense forces. If the ROK Army were expanded to double its present size, its combat efficiency would suffer as cadres were taken from the present units, Clark continued. To counter this watering-down, he recommended that the balance of the program be implemented as U.S. logistical capabilities permitted, with the emphasis being laid on the development of sound forces as well as U.S. personnel savings.29

In Washington, the Army G-3 approved Clark's note of caution. ROK manpower, General Eddleman pointed out, was not a limiting factor, but the scarcity of competent leaders from noncommissioned officers up to the corps level would restrict the effectiveness of the newly formed units. Since the United States would have to provide the bulk of the logistic support, including initial equipment, the Mutual Defense Assistance Program and NATO augmentation would both incur delay. Eddleman urged that Clark's moderate approach to the ROK Army expansion be adopted and that the problem of budgeting the cost of the programwhich could not be absorbed by the U.S. Army under present limitations-be taken up by the joint Staff.30

Secretary of the Army Pace and General Collins agreed that the time had come to consider the ultimate goal for ROK forces. On 17 November Pace passed the matter on to Secretary Lovett, as the implementation of the twentydivision program was beyond the purview of the Army. The broader aspects of such an increase would involve the over-all conduct of the war in Korea, governmental relations with nations who were recipients of Mutual Defense funds, and the structure of the federal budget, Pace declared, but the Army favored the establishment of a ROK capability to man the entire battle line as quickly as possible.31

Although Mr. Lovett turned the problem over to the JCS early in December, there was small chance that a decision would be reached until the new administration took over in January. Both President-elect Eisenhower and his designated Secretary of Defense, Charles E. Wilson, were briefed in the interim on the implication of raising a twentydivision ROK Army. General Collins pointed out that 105-mm. and 155-mm. howitzers and certain types of ammunition were the most critical items of equipment and supply that would have to be considered, but the main question remained that of financing the program. In the past, the Chief of Staff declared, there had been no specific Congressional authority for the Army's support of ROK forces. There was, however, tacit approval; Congress had been informed and had voted appropriations for the Army to provide replacement of equipment furnished the Republic of Korea. Collins felt that the expansion program was feasible: if the current stalemate continued and the enemy did not increase his forces appreciably; if a supplementary two billion dollars were added to the Army budget for fiscal year 1954 and the cost of supporting twenty divisions were budgeted far in advance; and if estimated delays in the completion of the NATO program and in the provision of normal artillery strength of four battalions for all the ROKA divisions were accepted.32

As the Republicans under President Eisenhower took over control of the government in January and began to weigh the pros and cons of the ROKA expansion, events in Korea provided an additional impetus to their deliberations. The ROK induction machine, still working in efficient fashion, had continued to train replacements at a brisk pace. By mid-January Clark had informed the JCS that if the present induction rate were maintained, all major ROKA units would be overstrength by the end of the month. It was basically the same problem as before; curtailment would interrupt the flow of trainees and entail a loss of time if the operation were to be resumed at a later date. Since cadres and replacements for two more divisions were now available, Clark recommended approval of the activation of two divisions in January and the raising of the strength ceiling to 460,000, exclusive of KATUSA. If possible he would like to have the entire ten-division augmentation approved in principle and theater stocks expended in outfitting the eleventh and twelfth ROK divisions expeditiously replaced.33

While the decision was pending, the JCS told Clark that he should proceed under the assumption that favorable action would be taken in Washington.34 On 31 January Clark instructed Van Fleet to go ahead with the formation of the 20th and 21st ROK Divisions and three days later official permission came from the President for fourteen divisions and six separate regiments. Including KATUSA and marines, the new ceiling would be 507,880. On 9 February Van Fleet activated the two new divisions.35

The pattern for permitting the ROK induction machine to generate pressure for the formation of additional organized units seemed likely to continue. Since the Eisenhower administration favored the increased use of indigenous forces in order to lessen the eventual demands on the United States, the chief problems in the future, as in the past, would center upon the timing and the financing of the expansion. In the meantime, the ROK Army began to take on the proportions of a well-rounded force. By January, five of the ten original divisions had been assigned organic artillery of three 105-mm. and one 155-mm. howitzer battalions, and the other five were being supported as they entered the line by a full complement of four ROK artillery battalions. Seven ROK tank companies were operational and each had twenty-two M36 medium tanks mounting 90-mm. guns. The eighth and ninth tank companies were expected to become operational in March and April.36

Although Clark and Van Fleet were in favor of adding a second Korean Marine regiment (less one battalion) and another 105-mm. howitzer battalion to provide a Marine force of 23,506 men, they opposed further expansion. The small ROK Navy did not have the personnel or sea transport to support a larger Marine Corps, they maintained in February 1953, and there were no known or anticipated requirements for such a force. If equipment were committed for developing more Marine units, they went on, the ROK infantry division program would be delayed.37 Clark also urged that the ROK Air Force strength of 8,600 men and one F-51 fighter wing be maintained. The JCS agreed in February that the ceiling should be 9,000 personnel rather than the 11,550 desired by the ROK Government.38

The growing military strength of the Republic of Korea was matched by its mounting economic instability. As more of its resources, both human and material, were devoted to the prosecution and support of the war, inflation increased. The large U.S. demands for advances of ROK currency to sustain the UNC forces were the main target of ROK complaints on the shaky status of the South Korean financial position, but as already indicated, this was but one cause. To help stabilize the Korean economy, the United States went on making its dollar payments during the winter. In December, Clark paid the ROK Government over $8,500,000 for the won advances of October and November, bringing the total of payments to over $74,000,000.39

Although the unofficial rate of exchange was over 20,000 won for one dollar, the ROK officials insisted upon maintaining the old 6,000 to 1 rate in its dealing with the U.N. Command. Negotiations between the ROK and UNC in January 1953 found the former striving to gain a settlement of $87,000,000 for all advances up to 16 December 1952. the agreement reached in late February, the United States agreed to pay a total of $85,800,000 for advances through 7 February, but secured ROK agreement to a quarterly adjustment of rate of exchange that could more accurately reflect the actual value of the ROK currency.40 The influx of American dollars, coupled with a ROK currency conversion in February that forced the South Koreans to turn in all their won for new whan at a 100 to 1 rate, was expected to ease the crisis somewhat, at least for the time being.41 But the indications grew as spring approached that the ROK Government intended to push for increased U.S. support of the South Korean war effort to alleviate the internal economic situation.42

Across the Sea of Japan, the efforts of the United States to strengthen its bulwarks met with a different response. The Japanese seemed content to hold their defense forces at the fourdivision, 110,000 man level until the political climate of opinion became favorable to a change in the Constitution that would permit armed forces to be raised legally. In the meantime, the funds set aside for equipping the proposed tendivision Japanese defense forces were held in abeyance, pending the conclusion of a Japanese-U.S. bilateral agreement.43 By February 1953, the Department of Army estimated that only $350,000,000 of the $528,600,000 allocated for Japan would be expended by the end of the fiscal year, because of the Japanese reluctance to build up their forces further.44 Under these circumstances, the lion's share of the available equipment went to the ROK and the imbalance between Japanese and ROK armed strength became greater. The Japanese lack of enthusiasm only provided a stronger stimulus for the growth of the military power of the Republic of Korea.

The Reorganization of the Far East Command

Since the winter of 1952-53 reflected in many ways the eagerness of the United States leaders in Washington and in the Far East to conserve manpower at the front, it was not surprising that retrenchments in the administrative and housekeeping functions in the rear should also be considered. Shortly after Clark assumed command, he decided to make a careful study of the command organization of the FEC.

The Koje-do crisis had demonstrated the weakness of the Eighth Army commander's relationship with his rear areas and one of the first steps that Clark had taken was to establish a separate Korean Communications Zone on 10 July 1952. By relieving Van Fleet of concern over his lines of communications, logistical support, prisoners of war, and civil affairs, Clark hoped to give the Eighth Army commander more time "to fight the war without having to look over his shoulder to keep tabs on what was happening in the rear areas."45

With headquarters at Taegu the Korean Communications Zone, under General Herren, extended over the southern two-thirds of the Republic of Korea. Its new responsibilities included the prisoner of war camps, supply movement and stockpiling, maintenance of ports and railroads, and co-ordination of relief and reconstruction work insofar as was possible under the divided authority existing between the UNC and other U.N. agencies.46

As the separation of combat and service functions on the Korean peninsula got under way, Clark decided to reorganize his Tokyo headquarters into a truly joint command. Under MacArthur and Ridgway, the Far East Command staff had consisted almost entirely of Army officers and enlisted men. Ridgway had considered the possibility of setting up a joint staff, but had not gotten around to putting the plan in effect before his departure.47

As noted in the previous discussion of the channels of command, there was a U.S. Army Forces, Far East, on paper, in 1951, but it had no staff and was not operational. (See Chart 1.) Instead the Eighth Army operated on the same level as the Naval Forces, Far East, and the Far East Air Forces, despite the fact that it was technically below them in the chain of command. To dispel any resentment that this arrangement may have incurred among Navy and Air Force commanders, Clark decided to staff the Army Forces, Far East headquarters, and place it on a par with the top naval and air commanders. He would remain Commanding General, U.S. Army Forces, Far East, as he had been before, to avoid the necessity for putting another four-star general senior to Van Fleet in the position. When Clark informed the JCS of his intention on 20 August, he noted that the Army Forces, Far East (AFFE) command would eventually replace the Japan Logistical Command. This would make possible the elimination of subordinate commands, such as the Northern, Central, and Southwestern Commands as well as the Headquarters and Service Command in Tokyo.48

On 1 October the Japan Logistical Command was discontinued and all of its functions were transferred to AFFE. At the same time the Northern Command of the Japan Logistical Command was also abolished.49 Clark appointed General Harrold as his deputy in command of AFFE, and staff sections from the Far East Command were assigned to perform similar functions in the new organization. Later in the month, Clark set up a manpower board to survey the requirements of AFFE and the rest of the joint FEC staff. He estimated that the reorganization would take until the end of the year and would release initially over 1,100 military spaces for reallocation in addition to saving a considerable number of U.S. and Japanese civilian spaces.50

With the establishment of AFFE, Clark proceeded to the second task of making the Far East Command a joint organization in the hope that if the other services shared the top assignments and the personnel burden, "it would increase the effectiveness of the team play that was so needed in Korea."51 His first inclination was to assign the J-1 (Personnel), J-3 (Operations), and J-5 (Civil Affairs) slots to Army officers, the J-2 (Intelligence) position to an Air Force officer, and the J-4 (Logistics) task to a Navy officer.52 But when the joint Staff began its operation on 1 January 1953, J-1, J-2, and J-3 were filled by the Army and J-4 and J-5 were manned by Navy officers. It was not until after the armistice was signed that an Air Force general took over the operations job. Three deputy chiefs of staff, one from each service, were set up under General Hickey, the chief of staff, to provide additional triservice representation.53 )

FAR EAST COMMAND STAFF AND MAJOR COMMANDS ORGANIZATION, 1 JAN 1953

Thus the FEC entered the last stages of the war with an organization that finally conformed to the concept of a joint command. Whether the change would have a real effect upon the conduct of a static war would be difficult to determine, since the prospects for facing major challenges seemed remote. Nonetheless, the arrival of Navy and Air Force officers to fill positions on the joint Staff meant that the Army could expect further personnel savings in this area. And if the battlefield erupted in grandiose fashion, General Clark's team might be in better shape to organize its defenses and prepare for the counterattack more quickly.

Notes

1 Under these standards, eleven months in the close combat zone (11 x 4) would be enough to make an enlisted man eligible for rotation.

2 Hq Eighth Army, Comd Rpts, Oct and Dec St, sec. I, Narrative, p. to and p. 13, respectively.

3 (1) Hq Eighth Army, Comd Rpt, Mar 52, G-1 sec., p. 3. (2) Ibid., Jun 52, sec. I, Narrative, p. 83.

4 Memo, Watkins for Bendetsen, 28 Aug 52, no pub, in FEC Gen Admin Files, Aug 52. It should tot be inferred that the service units at the rear were uninterested in the point score, but there was less at stake here- time not life.

5 Msg, DA 920367, Hull to Clark, 7 Oct 52.

6 (1) Msg, C 57617, Clark to Collins, 24 Oct 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Nov 52, incls 1-8g, incl 32. (2) Msg, C 58392, Clark to Collins, 6 Nov 52, in same place, incl 33,

7 Msg, DA 925905. CSUSA to Clark, to Dec 52.

8 Hq Eighth Army, Comd Rpt, Oct 52, sec. I, Narrative, pp. 68-69.

9 FEC G-3 Staff Study, Sep 52, title: Defensive Capabilities of Eighth Army, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Sep 52, an. 4, pt. III, Paper 3.

10 Hq Eighth Army, Comd Rpt, Dec 52, sec. I, Narrative, p. 1, gives the following figures:

| Date | UNC | Enemy |

| Arty | Mortar | Arty | Mortar |

| Oct 52 | 1,757,557 | 1,323,704 | 220,596 | 351,899 |

| Nov 52 | 811,203 | 857,996 | 106,203 | 189,750 |

| Dec 52 | 990,758 | 388,241 | 50,983 | 130,545 |

11 Ibid., Comd Rpt, Sep 52, sec. I, Narrative, pp. 61-65.

12 Ltr, Van Fleet to Clark, 3 Nov 52, no sub, in FEC Gen Admin Files, CofS, 1952 Corresp.

13 Msg, C 58517, CINCFE to CG Eighth Army, 8 Nov 52, in Hq Eighth Army, Gen Admin Files, Nov 52.

14 Report of Counter Battery Destruction Program IX Corps Artillery, 3-io November 1952, in Hq Eighth Army, Comd Rpt, Nov 52, bk. 8: Artillery, tab 2.

15 (1) Ltr, Clark to Van Fleet, to Nov 52, no sub. (2) Ltr, Van Fleet to Clark, 15 Nov 52, no sub. Both in FEC Gen Admin Files, CofS, 1952 Corresp.

16 (1) Ltr, Fifth AF to CG Eighth Army, 11 Nov 52, sub: Results of Thirty Day Flak Suppression Experiment . . . (2 ) Ltr, Eighth Army to CG U.S. I Corps et al., 13 Nov 52, sub: Artillery Fire During Air Strikes. Both in Hq Eighth Army, Comd Rpt, Nov 52, bk. 8: Artillery, tab 2.

17 Memo, Under Secy Army Johnson for CofS, 23 Oct 52, sub: Employment of Mortar vs. Artillery in Korea, in G-3 091 Korea, 103.

18 GAFF Staff Study, 21 Nov 52, title: Employment of Mortars vs. Artillery in Korea, in G-3 091 Korea, 103/2.

19 Msg, DEF 924436, Lovett to Clark, 2 1 Nov 52.

20 If the day-of-supply rate was 50 rounds for a particular caliber gun, the number of guns in the FEC of that caliber would be multiplied by go and then that total would be multiplied by go for ninety days of supply.

21 Msg, C 59373, Clark to Lovett, 23 Nov 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Nov 52, incls 1-89, incl 67. 22 Msg, C 59528, Clark to Van Fleet, 1 Dec 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Nov 52, incls 1-89, incl 68.

23 Hq Eighth Army, Comd Rpt, Jan 53, sec. I, Narrative, p. 126.

24 (1) Msg, CX 59611, CINCFE to DA, 3 Dec 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Dec 52, incls 1-78, incl 46. (2) Msg, DA 925751, G-3 to CINCFE, 7 Dec 52. The 159th Field Artillery Battalion and the 213th Field Artillery Battalion were converted to 240-mm. battalions on 20 March 1953.

25 For a detailed account of the matter, see U.S. Senate Committee on Armed Services, 83d Congress, 1st session, Hearings on Ammunition Supplies in the Far East.

26 Msg, C 61525, Clark to Collins, 16 Mar 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Mar 53, incls 1-72, incl 37.

27 Hq Eighth Army, Comd Rpt, Nov 52, sec. 1, Narrative, pp. 44-46.

28 Msg, CX 58279, CINCFE to CG Eighth Army, 1 Nov 52, in FEC G3 320.2 Strength No. 1, gives the following breakdown:

| Ground Forces | Strength |

Total | 462,920 |

| ROK Army | 415,120 |

| KATUSA | 28,000 |

| ROK Marines | 19,800 |

29 Ltr, Clark to CofS, 1 Nov 52, sub: Expansion in ROKA, in G-3 091 Korea, 77/2. Although Clark did not mention comparative costs in maintaining U.S. and ROK divisions, a study by the Eighth Army in November estimated that the monthly pay and rations for a U.S. division amounted to $6,104,164 as against $76,745 for a ROK division. See Hq Eighth Army, Comd Rpt, Nov 52, sec. 1, Narrative, p. 55.

30 (1) Summary Sheet, Eddleman for DCofS, 3 Nov 52, sub: Proposed Two Year Program . . . , in G-3 091 Korea, 75. (2) Memo, Eddleman for CofS, 4 Nov 52, sub: Development of Wartime ROK Army, in G-3 091 Korea, 73/3.

31 Memo, Pace for Secy Defense, 17 Nov 52, sub: Further Expansion of ROK Forces, in G-3 091 Korea, 76.

32 Memo, Collins for Bradley, 26 Nov 52, no sub, in G-3 091 Korea, 82. (2) Briefing for the Secy Defense Designate by the CofS, ca. mid-Dec 52, in G-3 337, sec. IV, 64.

33 Msg, CX 60941, Clark to JCS, 14 Jan 53, DA-IN 226714.

34 Msg, JCS 929141, JCS to CINCFE, 20 Jan 53.

35 (1) Msg, EX 40140, Clark to Van Fleet, 31 Jan 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jan 53, G-3 sec., pt. III, tab 5. (2) Msg, JCS 930325, JCS to CINCFE, 3 Feb 53. (3) Hq Eighth Army, Comd Rpt, Feb 53, sec. I, Narrative, p. 45.

36 Hq Eighth Army, Comd Rpts, Jan and Mar 53, sec. I, Narrative, pp. 42-43 and p. 53, respectively.

37 (1) UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Nov 52, pp. 36-37. (2) Msg, GX 2084 KGO, CG EUSAK to CG AFFE, to Feb 58 in Hq Eighth Army, Gen Admin Files, Jan-Jun 53. (3) Msg, CX 61365, CINCFE to DA, 28 Feb 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Feb 53, incls 1-88, incl 30.

38 Msg, JCS 931029, JCS to CINCFE, 11 Feb 53.

39 Hq FEC, Press Release, 12 Dec 52.

40 (1) Msg, CX 60997, CINCUNC to DA, 21 Jan 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jan 53, incls 1-67, incl 56. (2) Msg, CX 61338, CINCUNC to DA, 25 Feb 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Feb 53, incls 1-88, incl 48. The payment was made to the Korean Ambassador in Washington on 10 March.

41 Msg, CX 61258, CINCUNC to DA, 17 Feb 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Feb 53, incls 1-88, incl 51.

42 Msg, AX 73181, CG KCOMZ to CINCUNC, 28 Mar 53, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Mar 53, incls 1-72, incl 41. See Chapter XX, below.

43 Incl to Memo, G-3 for JSPOG, ca. to Dec 52, sub: U.S. Military Assistance to Japan, in FEC G-3 322.01, Commanders and staffs.

44 Msg, DA 931246, G-3 to CINCFE, 13 Feb 53.

45 Clark, From the Danube to the Yalu, pp. 145-46.

46 Hq Eighth Army, Comd Rpt, Jul 52, sec. I, Narrative, pp. 205-07.

47 See USAF Hist Study No. 72, USAF Opns in the Korean Conflicts, 1 Nov 50-30 Jun 52, p. 72.

48 Msg, C 53964, Clark to JCS, 20 Aug 52, in UNC/ FEC, Comd Rpt, Aug 52, CINCUNC and CofS, Supporting Docs, tab 3.

49 UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Oct 52, p. 3. Although the Headquarters and Service Command was also eliminated in early 1953, the Central and Southwestern Commands both endured to the end of the war and beyond.

50 Msg, C 57646, Clark to DA, 23 Oct 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Oct 52, CINCUNC and CofS, Supporting Docs, tab 45.

51 Clark, From the Danube to the Yalu, p. 133.

52 Msg, C 54992, Clark to JCS, 11 Sep 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Sep 52, CINCUNC and CofS, Supporting Docs, tab 1.

53 Clark, From the Danube to the Yalu, pp. 133-34.

Causes of the Korean Tragedy ... Failure of Leadership, Intelligence and Preparation