History  On Line

On Line

The frustrating conditions at Panmunjom and on the battlefield in Korea could not fail to affect domestic affairs in the United States during mid-1952. As long as the objective in Korea had been military victory, opposition to the expenditures of American lives, funds, and resources had not been difficult to cope with. But a slow process of reaction had set in, once the decision to end the war through negotiation was taken. The political and military leaders of the United States had to deal with a phenomenon new to them-limited war-and all its ramifications. With the passage of time and the failure to reach an agreement on a truce, criticism of the conduct of the war, set off by the Congressional investigation of the dismissal of General MacArthur in 1951, mounted.

To many people it seemed that the conflict in Korea had served its purpose. The North Koreans had been pushed back of the 38th Parallel and the Communists now knew that the United States would fight in the event of outright aggression. On the other hand, the United States and its allies had learned not to underestimate Chinese military strength. From all indications, both sides desired peace since little further gain could be expected from the stalemate. Only the principle of repatriation lay between the increasing casualty lists and the signing of an armistice.

How this obstacle was to be surmounted remained unclear, but it was inevitable that the settlement of the Korean problem should become the outstanding issue of the Presidential campaign of 1952. The debates, personalities, and political maneuvers of the race for the White House had but little effect upon the war itself, yet it was against this backdrop that events of the period unfolded. Both General of the Army Dwight D. Eisenhower, the Republican candidate, and Adlai E. Stevenson, his Democratic opponent, made peace the keynote of their platforms. The slackening of interest in military victory and the avowed intentions of both political parties to make an end of the Korean commitment meant that requests for additional manpower, expenditures, and resources would be closely scanned by both the executive and the legislative branch. In view of the election year atmosphere that fostered criticism of the administration's policies and the possibility-of which the Army was well aware-that there might be a change in the direction of the war if the Republicans proved victorious, mid-1952 was characterized by caution.

Reviewing the Alternatives

A radical change in the course of action being pursued in Korea was impossible under the circumstances. Although the military leaders in the field might chafe under the restrictions imposed upon them, there was little prospect that these would be altered except in detail. They could not be, in fact, without augmenting the military forces at the disposal of General Clark. It had been patent since July 1951 that, as presently constituted, the Eighth Army could hold the line and punish the enemy, but that was all. Limited war meant limited forces. One of the assumptions that military planners in Washington and the Far East had to contend with constantly in plotting courses of action was the dictum that the military strength of the Far East Command would remain substantially as it was.1 Only a return to fullscale warfare by the Communists or a breaking off of the negotiations could have caused a shift from this policy and, as noted earlier, the enemy seemed content to maintain the status quo.

Thus, the studies produced by the joint Chiefs in Washington reflected the static conditions in Korea and the political atmosphere in the United States. The Joint Staff Planners frankly admitted that the war in Korea could not be brought to a successful conclusion with the currently authorized force levels in the three services. If increased forces were sent to Korea, the strategic reserve in the United States would be depleted and allocations for Europe would have to be cut back. The alternative was an accelerated mobilization effort and this appeared to be out of the question. To maintain successfully the military pressure then being exerted upon the Communists seemed to warrant increases in ground, sea, and naval forces in the estimation of the joint Planners, but, until decisions on a national level established the long- and short-range objectives of the United States in Korea clearly, even this limited support was impossible. As they stated in May 1952: "At the present time we are faced with a set of conditions in Korea which preclude, from a military point of view, a conclusion which can be termed satisfactory. Under these unfavorable conditions, it is necessary to determine what immediate objectives and lines of action can be taken which will be least damaging to our national security, international prestige, and longrange objectives."2

The Washington planners seemed doomed to the same kind of frustration that hobbled their counterparts in the Far East Command. Unless the Communists erupted militarily in Korea or cut themselves off completely from the negotiations, intensification or broadening of the war, except in its air phase, was not likely to be considered. In the event the Eighth Army could not contain an enemy offensive, the conflict would probably no longer be limited to Korea, but might well become global in nature. If the Communists refused to continue the truce talks, however, the question of increased military pressure might again become vital and herein lay the weakness of the U.S. military position, for it did not have the strength in being to insure Communist acceptance of an armistice on UNC terms without leaving the United States and Europe unacceptably exposed. And any attempt to secure the additional personnel and means would have taken at least a year and required some additional industrial and manpower mobilization as well as a change in the global concept of placing the defense of Europe first.3

To be sure, the United States retained its atomic superiority, but the question of use of nuclear weapons in a mountainous area like North Korea which offered few worthwhile targets was still moot. In addition, the moral issue of whether the United States should employ atomic bombs again unless it were attacked had not been settled. It was doubtful that the United States would have initiated atomic warfare against a stubborn, but static enemy in Korea. This, then, reduced the U.S. position in Korea to a gamble that the Chinese did want peace and that the limited military pressure that the FEC forces could apply would secure that peace. In the meantime, the ROK and Japanese defense forces would be built up in the hope that they eventually would be capable of handling the Communist threat by themselves. This was the insurance policy that the United States took out against an interminable prolongation of the Korean affair. Eventually, whether an armistice was concluded or not, the nonKorean forces would be gradually withdrawn from the peninsula.4

Under these circumstances, planning for military victory appeared to be an academic exercise. The Joint Staff worked up plans and consulted with Clark's headquarters. In Tokyo the Far East Command examined ambitious outlines of operations that would increase the military pressure on the enemy or carry the Eighth Army through to victory. But the hard fact remained that none of these plans could be carried out by the forces then at Clark's disposal. To a JCS query on 23 September for his comments on possible courses of action if the negotiations failed, Clark said that he could do little more on the ground front.

We confront undemoralized enemy forces, far superior in strength, who occupy excellent, extremely well-organized defensive positions in depth and who continue to provide themselves with sufficient logistic support. Under these conditions, it appears evident that positive aggressive action, designed to obtain military victory and achieve an armistice on our terms, is not feasible by this command with current forces operating under current restrictions. Only with increased forces and the removal of certain restrictions could the FEC mount intensified operations with some hope of winning success without "highly unpalatable personnel costs."

Clark did not think that the United Nations Command should take the losses inherent in decisive offensive operations unless it intended to carry the fight to the Yalu. Intermediate objectives would be costly and undecisive, he felt.5

Although Clark did not believe that the USSR would enter the Korean War if the UNC drove to he Yalu, his concept of military victory had no chance for acceptance on the eve of the elections or thereafter. It ran squarely against the trend that favored the quick liquidation of the Korean commitment by political action. It was well for Clark to be ready in the event of an unexpected change of conditions, but the possibilities for such a shift were remote. The alternatives to a continuation of the policy of seeking a political settlement backed by limited military pressure in the field meant more men, more casualties, more expenditures, and more resources. By 1952 it was obvious that the era following the outbreak of the war when men, money, and materiel had been supplied on a comparatively liberal basis was over and the time for retrenchment was at hand. In this climate of opinion, broadening or intensifying the war to any great degree would appeal to but few.

Budget, Manpower, and Resources

The Presidential budget message in January 1952 had foreshadowed the time of austerity. In previous estimates the JCS had hoped to build up military forces to what might be considered acceptable defense levels by 1954. Presidential budget restrictions now made this impossible for the Chief Executive cut back the funds requested by the services. By lowering the allocations he stretched the period of preparedness from 1954 to 1956. This meant that, in the opinion of the JCS, if the Soviet Union attacked in full force before 1956, the United States capacity to resist successfully would be reduced. Although the cuts would affect the Air Force's attainment of 126 modern combat wings primarily, the Army would also have to draw in its belt.6

In some respects, the lower budget request for the armed services was deceptive, for it was predicated upon the hope that the Korean War would be over by the end of the fiscal year. Extension of the war beyond 30 June 1952 meant that supplementary appropriations would have to be requested later on to take care of deficiencies. General Collins and his staff had found it difficult to plan their fiscal estimates on this restricted basis and in May he asked the JCS to press the Secretary of Defense again for consideration of the assumption that hostilities would continue through the next fiscal year, subject to review at the beginning of each fiscal quarter. In late June, Secretary Lovett agreed that the JCS could assume that the war would last until 30 June 1953 insofar as planning for fiscal year 1954 estimates was concerned.7

Nevertheless the original Army estimate of 22.2 billion dollars for fiscal year 1953 had been tapered down by the President and his budget advisors to 14.2 billion dollars and Congress had lopped off nearly two billion dollars more in July. This would mean that the combat readiness date for the Army would be postponed until fiscal year 1956 and the expanded production base for items such as trucks, tanks, and artillery would be reduced. In addition, Army personnel requirements would have to be lowered.8

In Secretary Lovett's opinion, the Army had only itself to blame for the budget cuts. He told Secretary of the Army Pace that Congressional committees invariably asked Army witnesses why they had not obligated the funds already advanced if the need for materiel were so great. Evidently the witnesses had not answered these questions satisfactorily, he went on, and could not as long as undelegated funds continued to pile up and production was not accelerated to turn the money into usable goods. He found the excuse of "no funds" offered by the Army "tiresomely threadbare."9

The failure of the Army to obligate all the funds previously voted by Congress was due in part to the administrative delays inherent in arranging and concluding large contracts with hundreds of firms. In this case the care and caution exercised by the Army in negotiating contracts redounded to its disadvantage. Instead of having all the moneys deemed necessary on hand at the beginning of the fiscal year, it seemed that the Army would again have to depend upon supplemental appropriations to cover future deficiencies in carrying on the war.

This piecemeal approach to financing the war on a contingent basis made it difficult for the Army planners to formulate firm programs, for frequently it took eighteen months to two years to secure production of many items and few could guess how long the war would drag on. But the knowledge that money could be gotten if the need could be demonstrated was at least comforting. In the field of manpower, the situation was more serious and the prospects were less encouraging.

During the remainder of 1952, most of the men called into service during 1950 would have completed their two years of duty and would be eligible for discharge. Almost three-quarters of a million trained troops were scheduled to be released and an estimated 650,000 raw recruits would replace them. To train this tremendous number of men, the Army would have to devote about 25 percent of its total manpower to this task alone. If hostilities did not end shortly, the effective strength of Army forces in the United States would be limited to one airborne division because of the influx of the untrained troops. Other divisions would be undermanned and would have to be utilized as replacement and training divisions. To cope with the problem, General Collins urged the JCS in June to support his request for an increase of 92,000 men for overhead for the Army.10 Although Mr. Lovett tried to secure this augmentation, he ran into opposition from the Bureau of the Budget and the National Security Resources Board and was unsuccessful. From a total of almost 1.7 million in April 1952, Army personnel steadily shrank to about 1.58 million at the end of October.11

Cuts in personnel required reduction of officer strength as well. In the Far East Command the Army officer strength was to be cut by almost six hundred officers because of the budget limitations. Clark protested vigorously but G-3 informed him in June that the reduction on a world-wide basis had amounted to 5 percent. In the case of the FEC, Korea had been excluded and the actual cut had been made on the officer strength in Japan and the Ryukyus; otherwise it would have been more.12

At the end of July, G-3 suggested to Clark that he might be able to decrease the number of officers training the Japanese defense forces and give additional responsibility to Japanese instructors at battalion level and below. If U.S. officers could be confined to the higher echelons, the saving would help meet the anticipated over-all shortage of officers. Clark, in his reply, asserted that the Japanese forces would experience a large turnover in trained personnel in late 1952 as two-year enlistments expired and were also about to undergo training in heavy armaments that would preclude a reduction of U.S. officers for the present.13

In a frank letter to Clark on 1 August, General Collins discussed Army personnel prospects for the year ahead. The loss of half of the strength of the Army and the huge problem of training all the new replacements would sharply affect the status and quality of the reserve forces in the United States. Each month, Collins continued, the Army had to send 40,000 replacements overseas and this demand could be met until November. After that, FEC would receive its full quota, but other areas would go understrength. Collins felt that this would be a difficult period and much would depend upon the character of leadership at all echelons, if the Army were going to weather it successfully.14

The tone of Collins' letter left no doubt but that the Army manpower situation would deteriorate further. As ROK forces became trained and demonstrated their ability to take on further responsibility, they would replace the U.S. troops in the line. If the status quo in Korea continued, the U.S. contribution would be gradually diminished.15

The changing attitudes to U.S. funds and manpower were also reflected in the distribution of resources during the mid-1952 era. When General Clark in May voiced his concern over a possible Communist air build-up in North Korea once an armistice was concluded, and asked that his fighter force be increased by four F-86 fighter-interceptor wings and eight automatic weapons battalions to counter this threat, the joint Chiefs were sympathetic. But after carefully surveying F-86 production and the availability of antiaircraft units, they could only offer limited support. By October, the JCS informed Clark in early July, the F-86 Sabres that had been promised him in February would be delivered. In addition, 65 Sabrejets and 175 F-84's would be diverted to the FEC from other commitments to bring all FEAF fighter wings up to full strength and provide a 50-percent reserve. To help out on the defense of Japan, the JCS continued, one Strategic Air Command fighter wing of 60 F-84's would be deployed to Japan on a rotational basis. As for the antiaircraft battalions, one 90-mm. gun and two automatic weapons battalions could be provided by taking them from the continental United States defense forces.16 Although the provision of these air and antiaircraft units and equipment involved some risk in spreading out very thinly the forces not involved in the Korean War, the JCS attempted to scrape together at least part of what the FEC requested.

Ammunition Again

One of the problems that continued to plague the Army during the summer and fall of 1952 was the supply of ammunition. As noted earlier, there was little expectation that conditions would improve noticeably before the end of the year.17 And if the war waxed hot in Korea once more, even an increase in production would do little more than replace the rounds expended.

At a briefing in late April, the Army chiefs in Washington were informed that in the five major deficient categories- 60-mm., 81-mm., and 4.2-inch mortars, 105-mm. and 155-mm. howitzers- the situation was especially serious. If war broke out in Europe on 1 January 1953, the United States would only be able to supply six divisions with these five types of rounds and a year later the total that could be kept in action would be fifteen divisions. Current U.S. ammunition production facilities by early 1953 would have reached their maximum capacity and it would take another year and a half before new ones could be brought into production. When Secretary of the Army Pace heard about this, he directed that the entire question of expanding the ammunition production base be re-examined.18

Early in May another discordant note sounded from. Korea. A newspaper story claimed that the American soldiers were fighting with secondhand equipment and a shortage of ammunition. When the Army asked the Far East commander to comment, he replied that ammunition was plentiful and rationing was a normal military precaution. Since this information seemed diametrically opposed to the stand then being taken by General Collins before Congress to secure addtional funds for ammunition, G-3 asked FEC to explain further. As it turned out, the theater staff had based its estimates upon action on the battlefield continuing at the limited pace of the April-May period. If the action should quicken, the ammunition situation might alter radically. The one round whose supply did appear to be in a precarious position considering proposed production schedules in the United States was the 155-mm howitzer shell, the theater staff concluded.19

The dependence upon restricted operations at the front to maintain ammunition levels came to the fore again in early June. When Van Fleet toured his corps headquarters, he discovered that it had been necessary to limit deliveries of 105-mm. and 155-mm. howitzer shells to the other corps in order to provide the U.S. I Corps with adequate quantities for its missions. The corps commanders were aware that the situation would become even more complicated as additional ROK battalions were activated and supplied.20

By the end of June Clark had become gravely concerned over supplies of the 155-mm. howitzer shell. The Communists had almost doubled their artillery and mortar fire during the month and the Eighth Army had to increase its expenditures in self-defense. As mentioned earlier, the 105-mm. howitzer was not effective against enemy bunkers and lacked the range for counterbattery fire. Clark pointed out that when the 6 ROK 155mm. battalions became active, the FEC would have to supply 486 pieces instead of 378. Although the authorized day of supply was 40 rounds per tube, Clark had had to restrict the expenditures to a bit over 15 rounds a day. If the scheduled delivery of 155-mm. ammunition during the summer were maintained, only 140,000 rounds would arrive in the FEC and this would require further limitations. By 1 September, Clark concluded, theater stocks would be reduced to about 350,000 rounds or only 62 days supply instead of 90.21

General Collins recognized that the situation in the Far East Command was far from ideal, but he relayed several hard production facts to Clark in early July. At the present, only about 100,000 rounds of 155-mm. ammunition were coming off the lines each month and this would gradually climb to 650,000 rounds a month in approximately a year. To provide Clark with the full 40 rounds a day for 486 pieces would require about 583,000 rounds a month, a rate that would not be reached until March 1953, Collins continued. The most the Army could provide, without leaving Europe critically short and eliminating firing in training, would be on the order of 400,000 to 500,000 rounds during the 1 July-31 October 1952 period. Of course, Collins went on, in the event of a major attack, the Eighth Army could fire whatever was necessary to halt it, but it would take time to replace ammunition expended at a higher daily rate than 15 rounds. If the steel strike, which had begun on 2 June, lasted for a considerable length of time, Collins felt that improvement in the situation would be delayed further.22

Actually the Christie Park plant at Pittsburgh which produced over 60 percent of the 155-mm. shell forgings had already lost production of 60,000 forgings during the first month of the strike. Secretary Pace urged Mr. Lovett on 5 July to bring this loss to the attention of both labor and management in the hope that further damage might be averted.23

The urgency of the 155-mm. shell situation was reflected at the army and corps level in Korea several days later. Van Fleet informed his subordinates that the resupply rate through October would amount to about six to eight rounds per day and therefore the Eighth Army would employ its 155's only on the most remunerative targets, using other caliber weapons and tactical air wherever possible as substitutes.24

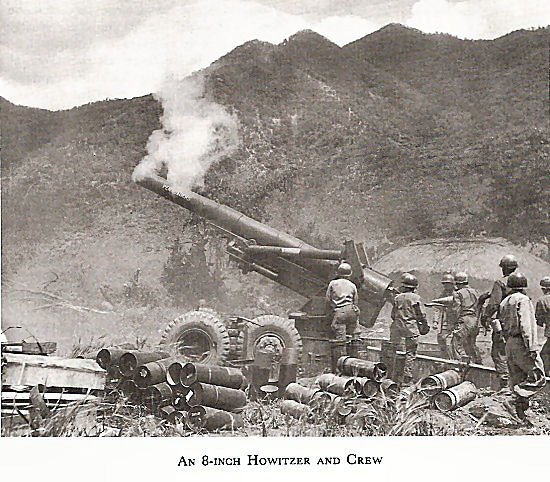

On 13-14 July, Collins and his deputy assistant chief of staff, G-4, General Reeder, visited Eighth Army and assured Van Fleet that he would get a minimum of five rounds of 155-mm. ammunition per day per tube including the tubes in the new ROK battalions. To help out during the emergency, Reeder suggested to Van Fleet that he might convert some of his 105-mm. to 8-inch howitzer battalions since tubes were available and ammunition was plentiful.25

Clark was not willing to let the daily rate rest at such a low figure and he authorized Van Fleet in early August to expend fifteen rounds of 155-mm. howitzer shells a day per tube. General Collins was able to secure approval of this rate later in the month by curtailing other allocations severely.26

To help alleviate the shortage, Clark had asked for permission to procure 600,000 rounds of 155-mm. ammunition (less explosives) in Japan. But when the Army discovered that the cost would be more than 60 percent over the U.S. rate, it turned down the request.27

However, the Army did agree in mid-August to replace ammunition expended in Korea. This would mean that a ninety-day level for the Korean area at the full rate of forty rounds per day per tube would be sought. When this was attained, Clark would only requisition ammunition on the basis of the number of rounds actually fired.28

As the action on the front mounted in September and October, ammunition expenditures on both sides climbed. In one week in September the UNC artillery and mortar units hurled over 370,000 rounds at the enemy and received over 185,000 in return. During the fierce battles of October, the Eighth Army sent 423,000 rounds of 105-mm. howitzer and 108,000 rounds of 155-mm. howitzer shells at the Communists in a six-day period.28

The sharply accelerated rate of fire per tube per day from less than 8 rounds of 155-mm. in September to 18 in October posed a new worry for General Clark. If the rate should continue, theater stocks would be reduced to 26 days of supply instead of 6o by the end of November."' The prospect led him to urge the Army to review its efforts to expedite deliveries and rebuild the theater stocks. Clark also pointed out that the 155mm. howitzer shells were not the only cause for concern. 81-mm. high explosive light shells for mortars and 155-mm. high explosive gun shells had been slow in arriving and what was more serious, only 355 fragmentation hand grenades had been shipped to the FEC between 15 August and 7 October.31

In its reply the Army assured Clark that it was doing all it could to improve the situation and that the supply picture was steadily becoming better.32 Some production was lost in the 155-mm. howitzer shell because of the steel strike and this had held down the delivery rate of this critical round. Yet in this and in the other rounds that were in short supply, the FEC got the lion's share. The real danger, General Reeder commented later on, lay in the precarious position of theater stocks in Europe. If hostilities had broken out there, the situation would have been disastrous.33

There were two points that should be kept in mind in considering the ammunition situation during the last two years of the war. First, there were no shortages of more than a temporary nature in the hands of the troops. Whenever it was necessary, the Eighth Army could use whatever ammunition it needed to protect itself. Secondly, despite the restrictions on the rounds per day during the more quiescent periods, the Eighth Army consistently fired far more ammunition than it received from the Communists. And this did not include the bombs, gun, and rocket fire launched by the UNC air forces. The troops could not fire as much as they desired all the time, it was true, but the picture was not all black. The bleakest spot was in the U.S. global ammunition situation rather than in Korea. Provided that Korean demands remained fairly stable, this condition would not be alleviated until production facilities reached their peak in 1953. In the meantime, restrictions would remain in effect and the dispute over shortages would continue.

The Expansion of the ROK Army

Discussion of the domestic problems of budget, manpower, and availability of resources for the Korean War could hardly avoid the closely related subject of the role of indigenous forces in the conflict. Since the United States wished to decrease gradually its commitments in the Far East, the contributions of the ROK, Japanese, Chinese Nationalist, and the armed forces of the other free nations in the area became more important. U.S. funds invested in native troops produced multiple returns, for the same amount of money would train, equip, and maintain more Far East nationals than Americans and by the same token should permit the United States eventually to reduce its responsibilities and its manpower in the theater. Whether the additional quantities of indigenous soldiers would also succeed in attaining a high degree of quality was as yet undetermined, but the improvement in the performance of some ROK units during the mid-1952 period was definitely encouraging.

With the replacement of General Ridgway by General Clark in May, there had been a change of attitude toward the enlargement of the ROK Army. Both MacArthur and Ridgway, it will be remembered, had favored a ten-division force Of 250,000 men as a desirable size and strength. But Clark was inclined from the start toward an expanded ROK Army. Several times during the first two weeks of his assumption of command, he remarked that the bigger the ROK Army was, the better he would like it.34

In reality the ROK Army had grown steadily above the 250,000-man level and had long been overstrength. Just before Ridgway had left the theater, he had submitted a new troop list totaling over 360,000 spaces, covering the additional artillery, tank, and security forces being organized and providing for ten additional infantry regiments.35 The tendivision ceiling had been retained, but the independent regiments could be used as cadres for new divisions if and when this became desirable.

Clark was thoroughly in accord with the expansion of the troop list. As he pointed out in June to the Washington staff, the ROK Army had supplanted the National Police in the corps areas and had taken on increased security duties in guarding prisoners of war and in suppressing guerrillas in the rear. In addition, the replacement and training system which produced seven hundred ROK soldiers a day had begun to pile up surpluses because of the low attrition rate at the front. To disrupt this smoothly functioning process, Clark reasoned, would not be wise, since it formed insurance against a period of heavy action. It should not be forgotten, Clark concluded, that there were 30,000 patients carried on the rolls because the ROK had no veteran's organization to care for them. Under these conditions, he felt that the Army should grant him authorization for 92,100 bulk personnel and 19,458 to form six separate regiments.36

Four days later, Clark followed up with another request. He wanted to add two more ROK divisions to the troop list and increase the total for logistical support from 363,000 to about 415,000. With the creation of the new divisions, Clark maintained, the number of Asians fighting communism would rise and the number of American casualties would decline. The ROKA replacement system would sustain the extra divisions and the six separate regiments, and help make the best use of South Korean manpower.37

As it turned out, the movement for expanding ROKA ground forces was not opportune. The Korean Ambassador to the United States, You Chan Yang, was at the time urging the State Department, the Air Force, and Congress to adopt a three-year plan for building up the ROK Air Force tactically.38 As already indicated, Ridgway had opposed the existence of a small, ineffective ROK air force which he thought would be annihilated at the outset by superior Communist air power.39 The objections to an augmentation of the ground forces stemmed from altogether different reasons. Owing to the shortages in artillery equipment and ammunition, ROK Army increases in these categories could be supported only by equivalent reductions in U.S. or U.N. forces that were being currently maintained. If there were to be an expansion in the ROK Army, both G-3 and G-4 preferred the increase to be in separate regiments that would not require additional artillery support rather than in divisions.40

The JCS, however, were not yet prepared to approve an augmentation of the ROK armed forces. At the end of June they decided to hold to the ten-division, 250,000-man Army and the existing Navy and Air Force.41

When General Collins visited Korea in mid-July, he approved raising the Korean Augmentation to the U.S. Army (KATUSA) to 2,500 men per division, but this was as much as he could do at the time. Clark had to inform Van Fleet not to activate further separate light infantry regiments and that ROK Army strength could not exceed 362,945 men. To insure that the replacement and training system did not cause the total strength to go over this figure, Clark told the Eighth Army commander to take action to separate the physically disabled and other nonuseful members of the ROK Army from the service.42

The Collins tour and his discussions with Clark and Van Fleet bore fruit in early August. The Chief of Staff overrode his staff by approving the requested bulk allotment of 92,100 men and directing Army support for a two-division augmentation for the ROK Army. As Collins envisioned the divisional expansion, it would be progressive and fitted within current budget guidelines and availability of logistical resources. He felt it would be desirable to capitalize on the ROK capability to supply trained manpower economically and to pave the way for the eventual withdrawal and redeployment of U.S. Army forces.43

While the JCS studied the implications of adding two divisions to the ROK Army, the strength of this army grew to over 350,000 men in August.44 Since KATUSA was not included in the ROKA totals, Van Fleet asked Clark to seek a further increment in KATUSA strength to a ceiling of 27,000.45 Clark agreed and urged the Army to permit up to 28,000 KATUSA soldiers to be distributed among the UNC units. Not only would the South Koreans bolster the fighting strength of the UNC organizations, 11e argued, but they would also receive the training that would make them the finest cadres.46

The FEC requests for augmenting the ROK Army and KATUSA were passed along to the JCS together with a third Clark recommendation covering the enlargement of the ROK Marine forces from 12,376 to 19,800.47 The Joint Chiefs also were reconsidering whether to allow the ROK Air Force to grow as Ambassador You had suggested in June. In mid-September, they determined to hold firm to their earlier position and maintain the ROK Air Force as it was.48

The following week the JCS approved Clark's plan for increasing the ROK Army, Marine forces, and KATUSA, lifting the troop ceiling for the ROK Army and marines to 463,000. In their memorandum to Secretary Lovett, the JCS admitted that to supply and equip the ROK increments would mean that the continental U.S. forces would have to go on operating under a 5o-percent ceiling on critical items, that 105-min. howitzers would have to be diverted from NATO programs, and that other critical items would have to be withdrawn from mobilization reserve stocks. Despite these disadvantages, the JCS felt that the opportunity to add more Asians to the fight against communism made the program worthwhile.49

On 1 October, on the heels of the JCS memo, Clark sent an urgent request for decision on the expansion of the ROK armed forces. The efficient replacement and training machine that was feeding the ROK Army seven hundred recruits a day was working all too well. In July the Eighth Army had tried a subterfuge to hold down the flow of recruits by carrying all the new trainees as civilians until they had completed basic training; otherwise the ceiling would have been exceeded in August. Rather than disrupt the steady input into the induction stations, the Eighth Army decided to gamble that the requests for ROKA increases would be approved ultimately and resorted to civilian trainees. If and when the augmentation were granted, the men would be trained and ready to go into the new units as they were organized.50

There were certain advantages to this procedure since it permitted the physically unfit and undesirables to be weeded out before they were sworn into the Army. But the delay in the decision at Washington had led to a crisis. The training cycle was only eight weeks long and by September the first civilian trainees were finishing the course and beginning to funnel into the Army officially. With casualties still at a moderate level, the new influx would soon send the ROKA total above the present ceiling. If the ROK Army were not going to be enlarged, Clark told the JCS, he would have to cut back the number of replacements to the current attrition level.51

Before the Secretary of Defense gave his support to ROK expansion, however, he wanted to know more about the impact of the program upon NATO, the Japanese defense forces, the Chinese Nationalist Army, and military assistance to the countries of Southeast Asia. General Bradley quickly informed him that deliveries of critical items like 105-mm. and 155mm. howitzers and 75-mm. recoilless rifles to other nations would be delayed by two months and that the necessity to supply ammunition for these weapons, if they were assigned to the ROK Army, would further limit the capability of the United States to provide ammunition for Europe and the zone of interior. As for other items that would be required, these could be furnished from Army mobilization and depot stocks.52

On 25 October, Mr. Lovett forwarded to the President his recommendation that the ROK forces be expanded with a new ceiling of 463,000 men and five days later Mr. Truman approved the proposal.53 In the meantime, the Republican candidate, General Eisenhower, had made his famous announcement that he would go to Korea if he were elected and had urged that the ROK forces be increased. On 29 October, at a political speech, he had read excerpts of a letter from Van Fleet to his former chief of staff, General Mood, in which the Eighth Army commander expressed his familiar theme that the ROK Army should be doubled from ten to twenty divisions so that U.S. forces could be released.54 Whether the political pressure of the campaign had an appreciable effect upon President Truman's decision would be difficult to ascertain, but it was possible that it might have speeded up favorable action.

At any rate, the first big step toward building a more formidable ROKA force had been taken and Eisenhower's victory at the polls in early November indicated that this move was only the forerunner of further developments along the same line.

The drive for expansion had garnered the major share of the attention during the summer and fall of 1952 and tended to throw into the shadows the other developments in the ROK Army. During April the ROK 1st Field Artillery Group of two 105-mm. howitzer battalions completed its training and in May moved into the line in support of the ROK 6th Division. By October eight of the ROKA artillery groups were available for duty and the remaining two would be ready before the end of the year. In the field of armor, four ROKA and one Korean Marine tank companies were operational by the close of October and three others were awaiting the arrival of tanks from the United States.55 The cadres of the six ROKA 155-mm. howitzer battalions authorized were sent out in June- one to each U.S. division. By November they were ready to take their battalion firing tests.56

The assignment of ROKA artillery battalions to U.S. artillery units in the combat zone complicated the problems of the latter considerably. In addition to surmounting the language barrier, the U.S. artillery commanders had to devote a great deal of time to the training of the ROKA outfits and to the finding of suitable firing positions for the ROKA pieces in their often crowded sectors.

To improve the caliber of the ROKA officer corps, Clark requested the Army in June to raise the allocations of student spaces in U.S. service schools to 581 for fiscal year 1953. Three months later, he asked that 100 spaces in the Artillery School and 150 spaces in the Infantry School be made available for ROKA officers in the session that was to begin in March 1953.57

Under Brig. Gen. Cornelius E. Ryan the Korean Military Advisory Group (KMAG) had almost 2,000 U.S. personnel assisting in ROK training by October, but the lifting of the troop ceiling to 463,000 betokened additional duties. Van Fleet levied twenty-four officers from his corps and divisions and channeled sixty-eight more from his pipeline into KMAG. Unfortunately, losses to rotation deprived KMAG of many officers and enlisted men during the last half of 1952 and imposed a heavy burden upon the KMAG staff.58

In mid-September, Van Fleet asked the ROK Army to increase the Korean Service Corps (KSC) from 75,000 to 100,000. He planned to form six new regiments and bring the existing units up to strength. Since members of the KSC served sixmonth terms, the ROK Army would have to bring in 4,000 personnel each week to keep the program at full strength.59

Crisis in the Rear

In addition to the support and training functions behind the lines, the ROK Army had to cope with security problems as well. Prisoners of war and the safeguarding of the lines of communication were two facets of this function. ROKA units joined other UNC forces in providing personnel to watch over the prisoner camps as they were dispersed in May and June. In the rural areas, guerrillas or bandits-it was difficult to distinguish one from the otherformed a constant threat to the lines of communication. In some sections the roads were unsafe during the hours of darkness and many farmers were afraid to cultivate their land even under the protection of guards during the day-time.60 |

|

Although guerrilla activity was mainly of nuisance value only, the bands operating in the important Pusan port sector assumed an important role in the development of the internal crisis in the ROK Government during the spring of 1952. The basic cause for the rise of domestic dissension lay in the conflict between President Rhee and the members of the National Assembly who opposed him. With the national elections destined to be held in the summer, Rhee determined to have the constitution changed so that the President could be elected by popular vote rather than chosen by the Assembly. His foes were equally resolved to keep this function in the legislative branch.61

On 24 May matters came to a head. Rhee placed Pusan under martial law and had some of his opponents in the Assembly arrested. Evidently he intended to dissolve the Assembly and have a new one elected to amend the constitution so that there would be a bicameral legislature and popular election of the President. At any rate, he charged the arrested assemblymen with complicity in treason in a Communist conspiracy and justified the continuation of martial law as a measure to counteract guerrilla operations in the Pusan area.62

The consternation caused by Rhee's actions was immediate both within and outside Korea. Political and military representatives of the U.N. and the United Nations Command sought to dissuade him from further steps that might result in weakening Korean democratic institutions and might endanger military operations at the front. Since the problem was primarily political, Clark and Van Fleet preferred to let the State Department handle the affair, although Van Fleet did go to see Rhee on 28 May, together with General Lee Chong Chan, the ROKA Chief of Staff, in an effort to persuade the President to lift the martial law edict.63 Rhee promised to consider this, but took no action.

In the meantime, Van Fleet took precautionary steps to safeguard the UNC personnel and installations. Security guards were reinforced and plans prepared to protect UNC troops, vehicles, and property from mob violence. Since the 1st Battalion of the 15th Infantry Regiment was engaged in prisoner of war duties at Pusan, Van Fleet ordered the unit pulled back to the United Nations Reception Center at Taegu to act as a mobile reserve. He warned General Yount of the 2d Logistical Command that extreme care should be taken to avoid participation in civil disturbances where no danger to the U.N. Command existed.64 As an added safety measure the JCS authorized Clark to divert up to a regimental combat team from Japan if the political situation deteriorated.65

The chief concern of the UNC rested in the uninterrupted flow of supplies to the front, since Pusan was the major port of South Korea and handled the bulk of shipments for the Eighth Army.66 But the State Department requested full support from the UNC in its efforts to alter Rhee's stubborn stand on martial law and the National Assembly and Collins instructed Clark to back the U.S. political representatives firmly.67

On 2 June President Truman sent a note to Rhee deprecating the loss of confidence in Korean leadership that was taking place and asking him to defer further action until Ambassador Muccio returned from the United States. e8 Truman's request may have given Rhee pause, for although he did not lift martial law, he evidently decided not to dissolve the National Assembly.

The impasse between Rhee and his legislature eased as they began to negotiate a compromise during June. It took the form of a constitutional amendment on 3 July that among other things provided for the popular election of the President and Vice President and the establishment of a second legislative chamber. Despite the clear-cut victory over his opponents, Rhee did not end martial law until 28 July.69

During the tense moments in late May and early June, the U.N. Command carefully watched the effects of the crisis upon the military supply lines and on the ROK Army. Since the political parties had abstained from interference in military logistics and Van Fleet had taken a firm stand against political tampering with the leadership of the ROK Army, Clark and Van Fleet were inclined to remain aloof and let the Koreans work out their own internal problems.70 They had supported the U.S. political representatives faithfully, if without great enthusiasm, in the efforts to end the Korean political war.71

While the guerrilla threat that Rhee had used as a reason for imposing martial law had not posed a significant challenge to either the ROK Government or the UNC, small-scale action of a bandit nature mounted during June. On 24 June guerrillas or bandits blew up a train in southwest Korea, destroyed eleven coaches, and killed over forty passengers.72

ROK Army and police units waged a constant skirmish with these predators- whose chief objectives seemed to be food and clothing. But despite the toll that the ROK forces exacted, the guerrilla bands managed to gain new recruits and to carry out harassing raids. In July the ROK 1st Division was pulled out of the line and sent to southwestern Korea to help eliminate the nuisance. This had been tried before with only moderate success and the ROK 1st Division had to undergo a similar experience. As the division moved through the mountainous Chiri-san region with National Police units attached, it met no organized resistance. The guerrillas followed the same pattern of dispersion and evasion that they used before. Breaking up into small groups until the ROK forces passed them by, they came together again afterwards and resumed their depredations. After a campaign of more than three weeks chasing the elusive bandits, the ROK 1st Division returned to the front and the National Police again resumed responsibility for the rear areas. From August to October, about three to four hundred guerrillas were reported killed and a hundred or so were captured each month, yet the over-all guerrilla strength declined very slightly.73

It was evident that the problem did not admit of an early solution and would probably continue. In Clark's opinion, however, hunting of guerrillas, like the settlement of political squabbles, was an internal ROK affair and in September he told Maj. Gen. Thomas W. Herren, commander of the newly formed Korean Communications Zone, that American soldiers could be used to guard prisoners, safeguard property, and protect supply routes and U.N. nationals, but not to chase bandits.74

Although the United Nations commander was able to remain neutral in the ROK domestic situation, he found it difficult to avoid participation in the republic's embroilment with Japan. Relations between the two countries, embittered by the controversy over Japanese claims to vested properties in Korea, were aggravated by the Japanese practice of fishing off the Korean coast. In September the ROK Navy seized several Japanese fishing vessels that had violated ROK territorial waters and tension mounted. Clark was forced to establish a sea defense zone on 22 September off the Korean coast, ostensibly to secure the UNC lines of communication and to prevent enemy agents from being landed, but in reality designed to form a buffer area between the ROK and Japanese vessels.75

Hardly had this uneasy moment passed when Rhee decided to put an end to the UNC practice of employing about 2,000 Japanese in Korea.

Most of the Japanese were working in port areas, installing equipment and training Korean replacements. But ROK resentment at the presence of its former overlords in positions of responsibility led Rhee to direct the arrest of all Japanese who came ashore without the permission of the ROK Government. Clark countered by instructing all Japanese employees to remain on shipboard except in case of absolute necessity. Since the Department of the Army did not wish Clark to make an issue of the matter, Collins told him to intensify his efforts to replace the Japanese with Koreans and to work out a program for doing this that Rhee might approve.76 In early October Clark passed these instructions on to General Herren, advising him that the emphasis should be put upon training Koreans quickly as replacements and upon an amicable solution of the altercation.77 |

|

Notes

1 See Memo, Col John T. Hall, G-3, for Chief Training Br G-3, 13 May 52, sub: The Effect on the Army of Possible Resumption of Hostilities in Korea, in G-3 091 Korea, 77.

2 JSPC 853/106, 9 May 52, title: U.S. Courses of Action in Korea.

3 Ibid.

4 Memo, Jenkins for CofS, 12 May 52, sub: Courses of Action in Korea, in G-3 091 Korea, 29/11.

5 (1) Msg, JCS 919187, JCS to CINCFE, 23 Sep 52. (2) Msg, CX 56022, CINCUNC to JCS, 29 Sep 52, in Transcript of Briefings G-3 091 Korea, 78.

6 JCS 1725/175, 20 May 52, title: Information for the Preparedness Subcommittee of the Senate Armed Services Committee.

7 (1) Memo, CofS for JCS, 21 May 52, sub: Assumption of Termination of Hostilities in Korea, in G-3 091 Korea, 1/15. (2) Memo, Lovett for JCS, 24 Jun 52, no sub, incl to JCS 1800/195.

8 Draft Statement of Secy Army before the Senate Appropriations Committee . . , ca. 10 Jun 52, in G-3 110, 10.

9 Memo, Secy Defense for Secy Army, 15 Aug 52, incl to Summary Sheet, Eddleman for CofS, 15 Oct 52, in G-3 091 Korea, 36/3.

10 Memo, CofS for JCS, 14 Jun 52, sub: Assumption of Termination of Hostilities in Korea, in G-3 091 Korea, 1/28.

11 (1) Memo, Jenkins for Taylor, 11 Jul 52, sub: Implication of Continued Hostilities in Korea, in G-3 091 Korea, 1/32. (2) STM30, Strength of the Army, 30 Apr and 31 Oct 52.

12(1) Ltr, TAG to CINCFE, 14 May 52, sub: Military and Civilian Personnel Authorization, in G-3 091, 46. (2) Msg, CINCFE to DA, 22 May 52, DA 141852. (3) Msg, DA 9?831, G-3 to CINCFE, 22 Jun 52.

13 (1) Msg, DA 914690, G-3 to CINCFE, 30 Jul 52. (2) Msg, C 53302, CINCFE to DA, 8 Aug 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Aug 52, and CinC and CofS, Supporting Docs, tab 47

14 Ltr, Collins to Clark, 1 Aug 52, no sub, in FEC G-3 320.2 Strength No.1.

15 Memo, Pace for Secy Defense, 16 Oct 52, sub: Reduction of U.S. Manpower in Korea, in G-3 320.2 Pacific, 13.

16 (1) Msg, CX 68196, CINCFE to JCS, g May 52, DA-IN 136993. (2) Msg, JCS 913020, JCS to CINCFE, 8 Jul 52.

17 See Chapter X, above.

18 (1) G-3 Memo for Rcd, 22 Apr 52, sub: Ammunition Supply Situation, in G-3 470, 4. (2) Memo, Col H. C. Hine, Jr., for Jenkins, 29 Apr 52, sub: Ammunition Supply Situation in FY 1958, in G-3 337, 23.

19 UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, May 52, pp. 129-30.

20 Hq Eighth Army, Comd Rpt, Jun 52, sec. I, Narrative, pp. 139-41.

21 Msg, CX 51020, Clark to Collins, 28 Jun 52, in Hq Eighth Army, Gen Admin Files, Jun 52, Paper 53.

22 Msg, DA 912775, Collins to Clark, 3 Jul 52. The strike was not settled until 25 July 1952 and endured fifty-four days in all.

23 Memo, Pace for Secy Defense, 5 Jul 52, sub: Opening of Christie Park Plant . . . , in G-3 470, 7.

24 Msg, GX 6904, CG EUSAK to CG I U.S. Corps et al., to Jul 52, in Hq Eighth Army, Gen Admin Files, Jul 52, p. 15.

25 Memo, Mudgett for Clark, 15 Jul 52, sub: Items of Personal Interest to CINCFE . . . , in UNC/ FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 52, CinC and CofS, Supporting Docs, tab 16.

26 (1) Msg, CX 53249, Clark to CofS, 7 Aug 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Aug 52, CinC and CofS, Supporting Docs, tab 62. (2) Memo, Ralph J. Watkins for Bendetsen, 28 Aug 52, no sub, in FEC Geri Admin Files.

27 Msg, DA 915309, G-4 to CINCFE, 7 Aug 52.

28 Msg, DA 915951, G-4 to CINCFE, 14 Aug 52.

29 Memo, Eddleman for DCofS Opns and Admin, 29 Sep 52, sub: Statistical Data, in G-3 091 Korea, 93/3. (2) UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Oct 52, p. 32.

30 Msg, CX 57223, Clark to DA, 18 Oct 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Oct 52, CinC and CofS, Supporting Docs, tab 51.

31 Ibid.

32 Msg, DA 922080, G-4 to CINCFE, 25 Oct 52.

33 Reeder, The Korean Ammunition Shortage, ch. VI, p. 9.

34 Memo, Moorman for CofS, 26 May 52, sub: Expansion of the ROK Forces, in FEC Gen Admin Files, CofS, 1952 Corresp.

35 Myers, KMAG's Wartime Experiences, pt. IV, pp. 43-44.

36 Msg, C 50459, Clark to DA, 19 Jun 52, DA-IN 152025. The bulk allotment included patients, trainees, interpreters, general prisoners, etc.

37 Msg, CX 50698, Clark to JCS, 23 Jun 52, DA-IN 153560.

38 Ltr, You Chan Yang to Bradley, 18 Jun 52, no sub, in G-3 091 Korea, 82.

39 See Chapter X, above.

40 Memo, Jenkins for CofS, 7 Jul 52, sub: Strength, Organizational and Logistical Support of Wartime ROK Army, in G-3 091 Korea, 74.

41 Decision on JCS 1776/281, 30 Jun 52.

42 (1) Memo, Mudgett for Clark, 15 Jul 52, sub: Items of Personal Interest to CINCFE . . . , in FEC Gen Admin Files, CofS, 1952 Corresp. (2) Msg, C 52744 CINCFE to Van Fleet, 29 Jul 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Aug 52, an. 4, pt. III, incl 3.

43 Memo, Brig Gen John C. Oakes, SGS, for ACofS G-g, 8 Aug 52, sub: Additional Logistical Support of War Time ROK Army, in G-3 091 Korea, 71/5.

44 The strength figures broke down as follows: 10 divisions, 144,420; corps troops, 16,004; Army troops, 101,113; bulk allotment, 92,100; total, 353,637. See Msg, CX 54184, CINCFE to DA, 25 Aug 52, DA-IN 176440.

45 At 2,500 men per division, KATUSA strength could reach 20,000 since there were 8 divisions- 6 U.S. Army, 1 Marine, and 1 Commonwealth. The other 7,000 would be placed in combat support units. See, Hq Eighth Army, Comd Rpt, Aug 52, sec. I, Narrative, p. 90.

46 Msg, C 55066, Clark to DA, 12 Sep 52, DA-IN 183011.

47 Msg, CX 54489, CINCFE to JCS, 1 Sep 52, DA 179035.

48 Memo, Brig Gen Charles P. Cabell for Secy Defense, 19 Sep 52, sub: A Three Year Plan for the ROK Air Force, in G-3 091 Korea, 60/5. It should be noted that this decision was somewhat deceptive, for the U.S. Air force had added twenty more fighter planes to the ROK Air Force between the JCS decision of 30 June and the end of September. See Ltr, Col C. C. B. Warden, TAG FEC, for JCS, 30 Oct 52, sub: Peacetime ROK Air Force, Marine Corps and Navy, in G-3 091 Korea, 74.

49 Memo, Bradley for Secy Defense, 26 Sep 52, sub: Augmentation of the Wartime ROK Army and Marine Corps, in G-3 091 Korea, 66.

50 Memo, GCM [Mudgett] for CINC, 20 Sep 52, sub: Strength of the ROK Army, in FEC G-3 320.2 Strength No. 1. (2) Msg, CX 56149, Clark for JCS, 1 Oct 52, DA-IN 190069.

51 Msg, CX 56149, Clark to JCS, 1 Oct 52, DA-IN 190069.

52 (1) Memo, Deputy Secy Defense Foster for JCS 8 Oct 52, sub: Augmentation . . . , incl to JCS 1776/322. (2) Memo, Bradley for Secy Defense, 10 Oct 52, sub: Augmentation . . . , in G-3 091 Korea, 66/8.

53 (1) Ltr, Lovett to the President, 25 Oct 52, no sub, in G-3 091 Korea, 66/17. (2) Memo, Lovett for JCS, 30 Oct 52, sub: Augmentation . . , G-3, Korea, 66/16.

54 New York Times, October 30, 1952.

55 Hq Eighth Army, Comd Rpts, May and Oct 52, sec. I, Narrative, pp. 41-42 and pp. 62-64, respectively.

56 Hq Eighth Army, Comd Rpts, June and Oct 52, sec. I, Narrative, pp. 73 and 63, respectively.

57 (1) Msg, CX 50924, CINCFE to DA, 26 Jun 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jun 52, an. 4, pt. II, J-17, 27 Jun 52. (2) Msg, CX 55484, CINCFE to DA, 20 Sep 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Sep 52, CinC and CofS, Supporting Docs, tab 55.

58 Myers, KMAG's Wartime Experience, pt. IV, pp. 8-10.

59 Hq Eighth Army, Comd Rpt, Sep 52, sec. I, Narrative, pp. 105-06.

60 Hq Eighth Army, Comd Rpt, Jun 52, sec. I, Narrative, p. 204.

61 UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jun 52, pp. 46-47.

62 Ibid., p. 48.

63 Msg, LC 893, Van Fleet to CINCFE, 28 May 52, in Hq Eighth Army, Opn Planning Files, May 52, item 106A.

64 Msg, GX 6155, CG Eighth Army to CG 2d Logistical Comd, go May 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, May 52, CinC and CofS, incl 27.

65 Msg, JCS 910146, JCS to CINCFE, 30 May 52.

66 Msg, C 69322, Clark to DA, go May 52, DA-IN 145040.

67 Msg, DA 910149, CSUSA to CINCFE, 31 May 52.

68 UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jun 52, p. 47.

69 Ibid., Jul 52, pp. 54-55.

70 (1) Msg, GX 74495 KCG, Van Fleet to Clark, 17 Jun 52, in FEC Gen Admin Files, CofS, Personal Msg File, 1949-5z. (2) Memo, Col Walter R. Hensey, Jr., G-5, for SGS, 19 Jun 52, no sub, in FEC Gen Admin Files, CofS, 1952 Corresp.

71 (1) Msg, GX 6632, Van Fleet to Clark, 24 Jun 52, in FEC Gen Admin Files, CofS, Personel Msg File, 1949-52. (2) Msg, GX 51399, CINCUNC to JCS, 5 Jul 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 52, CinC and CofS, Supporting Docs, tab 15.

72 Hq Eighth Army, Comd Rpt, Jun 52, sec. 1, Narrative, p. 204.

73 Hq Eighth Army, Comd Rpts, Jut 52, sec. I, Narrative, p. 6; Aug 52, sec. I, Narrative, pp. 80-81; Sep 52, sec. I, Narrative, p. 118; Oct 52, sec. I, Narrative, p. 66.

74 Msg, C 54962, CINCFE to CG KCOMZ, to Sep 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Sep 52, CinC and CofS, Supporting Docs, tab 6.

75 UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Sep 52, pp. 44-46.

76 (1) Msg, DA 919564, DA to CINCFE, 27 Sep 52, (2) UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Sep 52, pp. 46-49.

77 Msg, CX 56725, CINCUNC to CG KCOMZ, 9 Oct 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Oct 52, CinC and CofS, Supporting Docs, tab 55.

Causes of the Korean Tragedy ... Failure of Leadership, Intelligence and Preparation