History  On Line

On Line

Strategic and Tactical Air Operations

On the ground the Communist advantage in manpower was substantial, but the U.N. Command still had control of the air space over North Korea. Despite the build-up of the enemy air strength in Manchuria, the Communists made no serious effort to challenge the UNC dominance aloft during the spring of 1952. Fighters and bombers roamed at will with only occasional brushes with the enemy.

But a significant change in UNC aircombat operations policy came about in May. The rail interdiction program had reached the same status as the truce negotiations. As fast as the UNC pilots disrupted the rail system, Communist repair crews put them back in operation again. It was apparent that "to continue the rail attacks would be, in effect, to pit skilled pilots, equipped with modern, expensive aircraft, against unskilled oriental coolie laborers, armed with pick and shovel."1 If military pressure was to be maintained upon the enemy to influence the Communists to agree to a truce, then a shift from the diminishing returns of rail interdiction seemed in order.

Accordingly, in early May the scope of interdiction operations was broadened. Along the front, the Fifth Air Force's fighter-bombers concentrated their attacks upon enemy supplies, equipment, and personnel massed within striking distance of the battlefield, while medium bombers began to devote their attention to airfields, railway systems, and supply and communications centers, in that order. One of the first endeavors of the change came on 8 May when 485 fighter-bombers descended on Suan, about forty miles southeast of P'yongyang, and over a 13-hour period caused widespread damage to buildings, supplies, trucks, and gun positions in the biggest single attack of the war up to that time.2

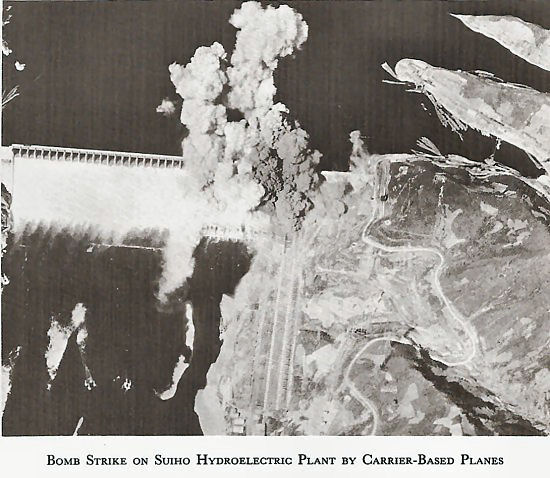

The North Korean Power ComplexAs interest in rail interdiction lessened, the search for profitable targets soon led the air planners back to the important, undamaged hydroelectric complex in North Korea. The location of certain dams and plants, such as that at Suiho on the Yalu, made them sensitive targets, since they furnished power to the Chinese as well as to the North Koreans. To avoid giving the Chinese an excuse to intervene, U.S. leaders had placed a ban upon the bombing of dams and plants along the Yalu on 6 November 1950 and it had never been rescinded.3 Later, when the truce negotiations began, the restrictions on Yalu power plant bombing had been repeated, but no mention had been made of the remainder of the power complex.4

Fearing that an effort to destroy the power installations might have an adverse effect upon the armistice proceedings, Ridgway had been reluctant to permit the Air Force to bomb them. In March 1952, he informed General Weyland that if the Communists appeared to be deliberately delaying an agreement and strengthening their offensive capabilities, he might change his mind, but in the meantime, he would not recommend an attack.5 It seemed to him that as long as the primary use of the power facilities was for the civilian economy, their destruction was not justified.6

General Weyland did not agree. In response to a request for his views on the matter from the Air Force planners in Washington, he stated that the disruption of electric power would complement other air attacks. By cutting off this power, the U.N. Command could make it difficult for the enemy to carry out repair work that was done in small establishments and in railway tunnels. Through reduction of small-scale production, Weyland went on, added pressure might be put on the Communists and spur them to speed up the negotiations. As for the means, Weyland estimated that 500 fighter-bomber and 80 medium bomber sorties could do the job over a period of several good flying days.7

It was not very surprising that Weyland's views should be communicated swiftly to the JCS by the Air Force or that Ridgway showed a little annoyance when the JCS questioned him on the divergence between Weyland and himself on the subject. The U.N. commander informed his superiors that there had been no unusual circumstances that would necessitate them to direct an attack upon the hydroelectric installations rather than follow the normal procedure of waiting for a recommendation from him. He was keeping a close watch on the situation, Ridgway concluded, and he did not want an attack unless he decided that it was warranted and opportune.8

On 12 May, Clark took over as Ridgway's successor. Shortly thereafter, he surveyed the situation and decided to intensify the air pressure campaign as much as possible. One of the most lucrative targets, he discovered, was the untouched hydroelectric complex. Although he did not have the authority to bomb the Yalu installations, he instructed Weyland to prepare plans for destroying all other major hydroelectric facilities. The Air Force would be the co-ordinating agent and the Navy would participate in the initial attack which was to be staged as soon as possible.9

When the Joint Chiefs learned of Clark's desire to strike the hydroelectric targets, they approached the Secretary of Defense to secure Presidential approval that would remove the restrictions on the Suiho plant, since this was the largest and most important installation in North Korea. President Truman's consent opened the entire complex to air destruction and the JCS told Clark to go ahead at his own discretion. The JCS warned that the ban on operations within twelve miles of the Soviet border still applied and care should be exercised not to bomb Manchurian territory inadvertently.10

Vice Adm. Joseph J. Clark, who had assumed command of the Seventh Fleet on 20 May, was anxious to have naval air units take part in the Suiho attack as well as those against other power targets.11 He flew to Seoul and easily convinced Maj. Gen. Glenn O. Barcus that he should allow Navy dive bombers and fighters to join the Fifth Air Force assault force.12 Thus, on 23 June, 35 Navy attack bombers (ADSkyraiders) and 35 Panther jet fighters (F9F's) from the carriers Princeton, Boxer, and Philippine Sea hit the Suiho plant while squadrons of Air Force Sabrejets (F-86's) provided overhead cover. The Navy dive bombers dropped their bombs while the Panthers provided antiaircraft suppression. As soon as the Navy planes completed their mission, 79 Thunderjets (F-84's) and 45 Shooting Stars (F-80's) followed and dropped their loads. Over 200 Communist fighters, perched on airfields across the Yalu, made no attempt to halt the attack; many of them took off in haste and flew inland.

During the next three days the Fifth Air Force mounted over 800 fighter-bomber sorties and over 200 counterair sorties while the Navy launched well over 500 sorties against the power system. Suiho was badly damaged, according to the pilot reports, and ten other plants were made unserviceable. Two installations suffered less vital hits. For two weeks a power blackout existed in North Korea with only gradual restoration thereafter.13

The bombing of the hydroelectric installations drew immediate fire in Great Britain from the Labour Party and from the press. Since the British Defence Minister, Lord Alexander, had but recently visited Clark, the British were upset that he had not been informed of the proposed strikes. Actually the Clark request had not been approved by the JCS until after Alexander had left Korea on 18 June, but it was difficult to convince the British on this score. The Churchill government narrowly survived a Laborite motion of censure after Secretary of State Acheson admitted in London that the United States had been at fault and should have consulted the Brtish beforehand. Although there was no compulsion for the United States to keep the British informed, Acheson said that they should have been told about the power plant operations as a matter of courtesy.14

Most of the British concern seemed to rest in the fears that the power plant destruction might lead the Chinese to break off the truce negotiations or to attempt retaliation. Clark later stated that he was somewhat surprised by the furor the attacks had caused in Britain, but was determined to repeat them, wherever profitable, until an armistice was concluded.15 It should be noted that although the Communist negotiators complained that the bombings were wanton, they neither ended the meetings nor sought revenge.

In the United States, the reaction was quite the reverse of that in the United Kingdom. The question of why the power complex had not been bombed earlier was raised in Congressional and other quarters. Clark could do little to help the JCS answer this query since he saw no reason why they should have been spared so long. On 19 July, Mr. Lovett told a congressman that seven factors had forestalled prior efforts to strike the power targets: 1. the postwar reconstruction problem; 2. the knowledge that some of the plants had been dismantled and only recently reconstructed; 3. the status of excess capacity in the plants; 4. possible losses of UNC air forces; 5. use of North Korean power in Manchuria and in the USSR and possibility that destruction of the plants might invite a Communist offensive; 6. estimated effect upon the armistice talks; and other priority targets.16 As it turned out, some of these factors had obviously been overrated or had become obsolescent.

One by-product of this flurry was the appointment of a British representative on the UNC staff. This had been discussed previously and rejected, since Ridgway had felt that making an exception in favor of the United Kingdom would lead to similar requests for representation from other U.N. countries participating in Korea. When Alexander visited Korea, Clark told the JCS that he was willing to accept a British staff officer despite the possible disadvantages. To counteract opposition criticism that had led to the censure motion, Churchill announced on 1 July that a representative would be named shortly. Actually, it was not until the end of the month that Maj. Gen. Stephen N. Shoosmith was designated as a deputy chief of staff of the U.N. Command. His directive, however, made it clear that his appointment was solely as a normal staff officer and that liaison between the United States and the United Kingdom would be carried on through normal political and military channels as it had been in the past, both in Korea and in Washington.17

At any rate, the bombing of the hydroelectric system became an accepted part of the air campaign. Suiho was subjected to a B-29 raid on 11-12 September and other plants were hit whenever they seemed to be getting back into operation.

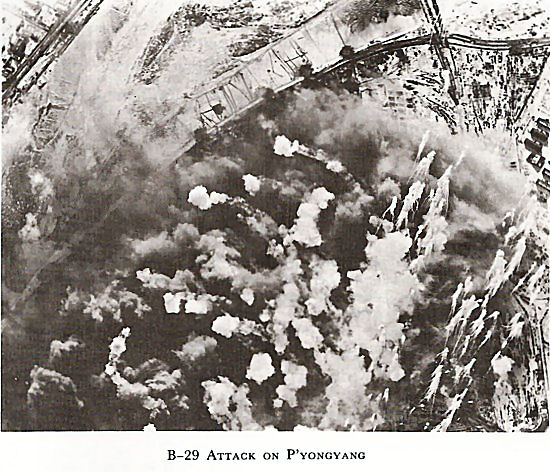

P'yongyang

During May the Far East Air Forces also proposed to mount another attack upon the North Korean capital of P'yongyang. New military targets near the city had been uncovered and could be destroyed, Weyland told Clark. The latter was not averse to a strike on Pyongyang, but he was worried about Prisoner of War Camp No. 9 which the Communists had placed close to the city. Since air reconnaissance had not located this camp, Clark wanted the Far East Air Forces to conduct the attack by visual means or with the assistance of shortrange navigational beacons so that the prisoner camp would not be bombed.18

On 5 July, subject to these conditions, Clark approved the operations against P'yongyang. In the course of eleven hours on 11 July, 1,254 sorties were flown. Fifth Air Force Sabrejets and Thunderjets, ROK and Australian fighters, British Meteors, and Navy Panthers and Corsairs from the Seventh Fleet vectored in three waves to hit the forty-odd targets in and around the city. When night fell, B-29's arrived to bomb targets specially reserved for them. Supply depots, factories, billeting areas, railway centers, and gun positions were destroyed and damaged and the Communist radio claimed that 1,500 buildings had been leveled and 900 others had suffered harm from the 1,400 tons of bombs and 23,000 gallons of napalm dropped on the capital. Despite heavy and accurate antiaircraft fire, only one air force and two naval fighters were lost. Eight air force planes, however, were seriously damaged.19

On 4 August the Fifth Air Force fighter-bombers hit P'yongyang again with 273 sorties, bombing buildings, a fuel dump, gun positions, and military personnel. A third huge effort against the city came on 29 August. Clark and Weyland decided that a psychological air blow should be struck while the Soviet and Chinese representatives were conferring in Moscow. In another three-wave assault, 1,403 Air Force and Navy sorties blanketed the capital and inflicted additional damage. After this pounding P'yongyang possessed too few worthwhile targets to warrant major strikes for a time.20

Air Pressure and Air-Ground Support

General Clark realized that although there was little he could do to increase the ground pressure against the Communists in Korea, he could give the Air Force and Navy full encouragement to step up the pace of the air campaign.21 The attacks on the power plants and on P'yongyang were the most spectacular during the summer of 1952, but by no means the only ones that were launched.

In late July 63 B-29's mounted their greatest single-target effort thus far against the Oriental Light Metals Company, an aluminum alloy plant within five miles of the Yalu River. Enemy jet and propeller-driven night fighters provided but slight and ineffective opposition to this raid, which inflicted heavy damage on the plant.22

On 27 July naval aircraft from the Bon Homme Richard attacked a lead and zinc mine and mill at Sindok and others from the Princeton bombed a magnesite plant at Kilchu the next day. On 1 September, carrier aircraft from the Essex, Princeton, and Boxer struck the oil refinery at Aoji, just eight miles from the Soviet border. Special permission from the JCS, enabled the Navy to send over 100 fighters and fighterbombers against the previously undisturbed oil supply center and reports indicated that the destruction was extensive.23

Despite the nearness of many of the Air Force and Navy operations to the Chinese border during the summer and the impressive fighter strength of the Chinese Air Force located just across the Yalu, enemy air activity was conspicuous by its absence. The MIG-15's generally avoided combat and the majority of the aircraft losses was due to antiaircraft fire. As the bombing of industrial targets increased in July and August, enemy aircraft began to be sighted more frequently, but they showed little disposition to fight. When they did, the Sabrejets usually took a heavy toll of Communist planes.24

The reluctance of the Communist fighters to defend their troops, cities, and plants offered a contrast to the efforts of the UNC air forces to afford their ground forces support during the summer of 1952. However, there had been complaints from ground force commanders regarding the Van Fleet-Everest agreement which had specified that 96 close air support sorties a day would meet Eighth Army requirements under conditions of limited ground activity.25 In December 1951, Van Fleet himself had sought in vain to have one squadron of fighter-bombers assigned to each of his corps, maintaining that this would improve close air support operations. The parceling out of air combat units ran counter to Air Force doctrine and had been firmly rejected on the grounds that such a system would be inflexible and wasteful inasmuch as the squadrons could not be shifted to the more active fronts as necessity arose. But Van Fleet was not easily dissuaded. After Clark became commander in chief, he tried again. Early in June he suggested that the 1st Marine Wing be placed under the operational control of the Eighth Army.26

Van Fleet's plan was essentially the same as it had been six months earlier. He would put one squadron under each corps commander and establish a joint operations center to control the use of the Marine units at each corps headquarters. To counteract the Air Force argument that this system would be inflexible, he intended to retain sufficient control at Eighth Army level to divert aircraft not being used adequately to other corps or back to the Fifth Air Force. The chief benefits, the Eighth Army commander maintained, would be to reduce the time lag between the request for support and its arrival; to allow the pilots to become familiar with the terrain that they would be called upon to attack and the ground personnel they would be working with; to increase the number of sorties per day by having the aircraft stationed close to the corps front lines; and to insure better control of air strikes by eliminating the spotter aircraft that now directed them.27

Although Clark sympathized with Van Fleet's approach, he had no desire to stir up the old feud between air and ground forces on the role of tactical aviation. On 1 July he turned down the Eighth Army commander's proposal and directed his staff to improve procedures for carrying out air-ground operations doctrine.28

Six weeks later Clark issued his plan for improving conditions. He did not find anything basically wrong with the present system. One of the difficulties, he maintained, was a lack of understanding at subordinate levels of the limitations of the air arm and of the fact that air policies were only arrived at after consultation between the Air Force and Army commanders. Clark felt that ground commanders frequently called for air strikes when their organic artillery could do the job better. After all, he went on, the air forces in the FEC had only limited forces and had many tasks to perform. The Army could not afford to adopt the Marine air-ground team system because it was not designed for the same kind of operations and had entirely different allocations of artillery to carry out its missions.29 Actually, Clark suggested, the tactical air forces were engaged in three types of action- antiair, antimateriel and installations, and antipersonnel. Ground support was not the least of these, although it seemed always to be mentioned last. He thought that cooperative training between the air and ground forces would do much toward eliminating many of the misconceptions that existed and proposed that steps be taken to allow more understanding of mutual problems.30

In the meantime, Van Fleet had consulted with General Barcus, Fifth Air Force commander, in June about applying the maximum air effort to destroy the enemy air offensive potential close to the battle front. He feared that the build-up of Communist strength close to the front might portend a possible offensive before the rainy season, so he urged de-emphasis of the rail interdiction program and increase in close air support. In addition, Van Fleet asked Clark to let the B-29's, which were running into mounting enemy night fighter opposition on their raids close to the Manchurian border, hit Communist personnel, supplies, and material close to the front lines by employing night radar-controlled bombing techniques.31

Barcus was willing. He informed Van Fleet that the air effort from the main line of resistance to areas forty miles behind the enemy front was growing substantially. But there were difficulties, he continued. Personnel and supply bunkers were extremely hard targets to destroy since the enemy was so well dug in.32 Admiral Clark, Seventh Fleet commander, was also eager to help. After a tour of the Eighth Army front in May and talks with Van Fleet, he came to the conclusion that naval aircraft were particularly well suited for the type of pinpoint attacks that would be necessary to hit enemy personnel and supply bunkers. Van Fleet and his ground commanders were all in favor of naval air aid and the Seventh Fleet staff began to lay plans for joining in the close combat support program.33

As the number of air support missions increased, fighter-bombers and medium bombers (B-29's) began to unload their bombs and guns on targets in the enemy's immediate rear. Van Fleet was encouraged. During the rainy season in July, he was successful in securing light bomber and medium bomber support from Barcus and Weyland, who were eager to co-operate if suitable targets could be uncovered for the heavier aircraft.34

There is little doubt that the end of the rail interdiction campaign opened a new and- to the ground forces- more satisfactory phase of the air war. The growing numbers of aircraft overhead meting out punishment to the enemy across the lines could not help but boost front-line morale. During the bitter battles of October, the U.N. Command air force flew almost 4,500 close support sorties against enemy personnel, equipment, supplies, and strongpoints, and of these over 2,20o were in support of Operation SHOWDOWN alone. General Jenkins, the IX Corps commander, sent his "grateful thanks" for the Fifth Air Force's outstanding assistance.35

As the ground and air force officers began to swap visits to the front and to the air control centers, some of the misunderstanding between the two groups started to fade. The ground troops learned that they could help the pilots by using proximity fuzes before air strikes to suppress antiaircraft fire. Since losses of friendly planes had mounted during the close support campaign because of heavy flak, the efforts of the artillery to reduce the hazard were appreciated by the air force. Another symptom of the change for the better, according to the official Air Force historian, came from Van Fleet himself. By fall he no longer was urging that air squadrons be assigned to his corps.36 This in itself seemed to denote an overall improvement.

The Kojo Demonstration

Naval surface operations during the summer of 1952 consisted mainly of routine patrol and blockade of the Korean coast, mine sweeping operations, and the shelling of targets along the coast to harass and interdict the enemy's lines of communication. For the ROK I Corps the naval surface guns provided splendid artillery support whether on offense or defense.

But the biggest naval operation was the demonstration at Kojo on the east coast of Korea. In July Clark had asked Vice Adm. Robert P. Briscoe, the naval commander, whether it might not be wise in the interest of economy to hold a landing exercise in connection with the movement of the 1st Cavalry Division's 8th Regimental Combat Team to Korea. Owing to housing difficulties in Japan, Clark had decided to rotate the three RCT's of the 1st Cavalry to Korea, one at a time. Since the first team was scheduled to be transferred from Japan in October, Clark felt that the opportunity for alarming the Communists should not be missed.

Admiral Briscoe was heartily in favor of some action and suggested that an amphibious demonstration be mounted. This could conceivably lure enemy reinforcements out on the roads and expose them to attack by air and surface craft. In addition, the training would be excellent for all the UNC forces involved, Briscoe concluded. Encouraged by this reception, Clark told his naval commander to go ahead with the planning and to co-ordinate with Eighth Army and XVI Corps staffs on the role of the 1st Cavalry Division units.37

Under Admiral Clark, the Seventh Fleet commander, joint Amphibious Task Force Seven was set up and 15 October established as the target date. The demonstration was scheduled for the area near Kojo and planning for the land, sea, and air phases proceeded at a swift pace. For purposes of deception, only the highest echelon of command knew that the maneuver was to be only a demonstration.38

Although the 187th Airborne Regiment was to be withdrawn and prepared for an airdrop and Eighth Army was to prepare for an offensive to link up with the amphibious forces, Clark told Van Fleet this was simply to confuse enemy intelligence and no more than limited land objectives would be attacked.39

On 12 October rehearsal operations held at Kangnung ran into high surf conditions and had to be broken off. For the next three days, FEAF and naval planes hit the enemy positions around Kojo and naval surface craft, led by the battleship Iowa, shelled the beach area. The assault troops climbed down to the assault landing craft in the early afternoon of 15 October and made a pass at the shore. Sudden high winds made recovery of the boats a difficult task, but there were no serious casualties.

The enemy response to the elaborate scheme was disappointing. Little evidence of significant troop transfers came to light and the Communist shore batteries threw only a few answering shells at the assault force. Whether this denoted a lack of mobility to respond quickly or perhaps a preference to wait until the UNC troops had landed and then to launch a counterattack was impossible to surmise. Evidently the discovery that the operation was only a feint added to the frustration of all the UNC personnel who had not been in on the secret. The realism of the planning and mounting of the operation had built up UNC expectations and although the training was adjudged valuable, the damage to morale served to balance this off.40

As operations tapered off in the fall, the results of the fighting during the May-October period remained open to speculation. Although the air pressure campaign had evoked some protests from the Communists at Panmunjom, it had in no way softened their attitude toward an early armistice on the UNC terms. On the ground the hill battles had caused the enemy more casualties than the UNC had suffered, but gains on both sides had been minor. and neither could claim a victory. Communist attrition in men, supplies, materiel, and installations was considerable during the six-month span, but they showed no sign of cracking or of submitting to a truce. From every aspect it was still a stalemate and no end was in sight.

Notes

1 USAF Hist Study No. 127, USAF Opns in the Korean Conflict, 1 Jul 52-27 Jul 53, p. 26.

2 Ibid., p. 27.

3 Ibid., pp. 27-30.

4 Msg, JCS 95977, JCS to CINCFE, 10 Jul 51.

5 Memo, EKW [Wright] for CofS, x Apr 52, sub: N.K. Hydroelectric Power Installations, in FEC G-3 091 Korea, folder 1, Jan-Feb 52.

6 Memo, MBR [Ridgway] for CofS FEC, 26 Apr 52, no sub, in FEC G-3 091 Korea, folder 1, Jan-Feb 52.

7 Msg, VCO 118, CG FEAF to Hq USAF, 29 Apr 52, 5285.

8 Msg, CX 67909, CINCFE to JCS, a May 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, May 52, an. 4, incl 2.

9 Msg, CX 50528, CINCFE to COMNAVFE and CG FEAF, 17 Jun 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jun 52, CinC and CofS, Supporting Docs, tab 15.

10 (1) Memo, Bradley for Secy Defense, 19 Jun 52, sub: Removal of Restriction on Attacks Against Yalu River Hydroelectric Installations. (2) Msg, JCS 911683, JCS to CINCFE, 20 Jun 52.

11 Clark succeeded Vice Adm. Robert P. Briscoe, who was appointed Commander, Naval Forces, Far East, on 4 June when Admiral Joy was rotated.

12 General Barcus took over command of the Fifth Air Force on 30 May from General Everest.

13 Msg, CX 50733, CINCFE to JCS, 24 Jun 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jun 52, CinC and CofS, Supporting Docs, tab 18. For more complete accounts of these raids, see: (1) R. Frank Futrell, The United States Air Forces in Korea, 1950-1953, (New York: Duell, Sloan and Pearce, 1961 ) , pp. 451-52: (2) James A. Field, Jr., History of the United States Naval Operations, Korea (Washington, 1962), pp. 436-39; (3) Malcolm W. Cagle and Frank A. Manson, The Sea War in Korea (Annapolis: U.S. Naval Institute, 1957) 1957), pp. 441ff.

14 Dept of State, Press Release No . 516, 30 Jun 52, in Dept of State Bulletin, vol. XXVII, No. 681 (July 14, 1952), p. 60

15 Clark, From the Danube to the Yalu, pp. 72-74.

16 (1) Msg, JCS 912750, JCS to CINCFE, 3 Jul 52. (2) Msg, C 51395, Clark to JCS, 5 Jul 52, DA-IN 157923.(3) Msg, JCS 914021 to CINCFE, 21 Jul 52.

17 (1) Msg, C 50318, Clark to JCS, 17 Jun 52, DA 151297. (2) Msg, DA 914543, Jenkins to CINCFE, 26 Jul 52.

18 UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jun 52, an. 4, pt. 1, p. 20.

19 (1) USAF Hist Study No. 127, USAF Operations in the Korean Conflict, 1 July 1952-27 July 1953, pp. 88-99. (2) Futrell, United States Air Force in Korea, 1950-53, pp. 481-82. (3) Cagle and Manson, The Sea War in Korea, pp, 450-53.

20 (1) USAF Hist Study No. 127, USAF Opns in the Korean Conflict, 1 Jul 52-27 Jul 53, p. 99. (2) Futrell, United States Air Force in Korea, 1950-53, pp. 483, 489.

21 Msg, CX 53391 CINCFE to CG FEAF and COMNAVFE, 8 Aug 52, in JSPOG Staff Study No. 410.

22 UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Jul 52, p. 28.

23 Cagle and Manson, The Sea War in Korea, pp. 454-59.

24 Futrell, United States Air Force in Korea, 1950-53, pp. 477-78.

25 (1) USAF Hist Study No, 72, USAF Opns in the Korean Conflict, 1 Nov 50-30 Jun 52, pp. 206ff. (2) USAF Historical Study No. 127, USAF Opns in the Korean Conflict, 1 Jul 52-27 Jul 53, pp. 184ff.

26 Msg, G 6262 TAC, Van Fleet to Clark, 6 Jun 52, in FEC Gen Admin Files, CofS, Personal Msg File, 1949-52.

27 Ibid.

28 (1) Memo, for CofS, 1 Jul 52, no sub, in UDC/ FEC, Comd Rpt, G-3 Jnl, J-g, 12 Aug 52. (2) Clark, Front the Danube to the Yalu, pp. 91-92.

29 The 1st Marine Division had the 11th Marine Regiment as its artillery regiment. The regiment had basically the same armament as the four separate battalions employed by the Army to support divisions-three battalions of 105-mm. howitzers and one battalion of 155-mm. howitzers. In Korea, it was part of a corps and received corps artillery support. Ordinarily, however, Marine divisions did not have corps artillery at their disposal to take care of the longrange, heavy-duty artillery tasks, and Marine air support was often used as a substitute.

30 Ltr, Hq FEC to CG Eighth Army et al., 11 Aug 52, sub: Air Ground Opus, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, G-3, Jnl, J-3, 12 Aug 52. See discussion in Chapter XVII, below, of the results of the experiments ensuing from this plan. See also USAF Hist Study No. 127, USAF Opns in the Korean Conflict, 1 Jul-27 Jul 53, pp. 197ff.

31 (1) Msg, G 6267 TAC, Van Fleet to CINCFE, 7 Jun 52, (2) Msg, G 6390, Van Fleet to CINCFE, 12 Jun 52. (g) Msg, GX 6490, Van Fleet to Barcus, 17 Jun 52. All in Hq Eighth Army, Gen Admin Files, Jun 52, Papers 20, 28, and 38.

32 Msg, CG 117, CG Fifth AF to CG EUSAK, 19 Jun 52, in Hq Eighth Army Gen Admin Files, Jun 52, p.43.

33 Cagle and Manson, The Sea War in Korea, pp. 461ff. The naval support program did not get under way until October. See Chapter XVII, below.

34 (1) Msg, G 6644 TAC, Van Fleet to Clark, 25 Jun 52, in Hq Eighth Army, Gen Admin Files, Jun 52, Paper 82. (2) Msg, GX 7229 KCG, Van Fleet to CINCFE, 31 Jul 52, in FEC G-3 Completed Actions. (3) Msg, CX 52915, Clark to Van Fleet, 1 Aug 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Aug 52, CinC and CofS, Supporting Docs, tab 17.

35 USAF Hist Study No. 127, USAF Opns in the Korean Conflict, 1 Jul 52-27 Jul 53, p. 188.

36 Futrell, United States Air Force in Korea, 1950-53. pp. 505-07.

37 UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Aug 52, p. 5.

38 Ltr, Clark to Collins, ? Sep 52, no sub, in FEC Gen Admin Files, CofS, 1952 Corresp.

39 Ltr, Clark to Van Fleet, 13 Sep 52, no sub, in FEC Gen Admin Files, CofS, 1952 Corresp.

40 See Cagle and Manson, The Sea War in Korea, pp. 391-96.

Causes of the Korean Tragedy ... Failure of Leadership, Intelligence and Preparation