History  On Line

On Line

I emphatically disagree with so-called military experts who say that victory was ours for the taking at any time during my period of command with the limited forces at our disposal and without widening the scope of the conflict. We never had enough men, whereas the enemy had sufficient manpower not only to block our offensives, but to make and hold small gains of his own .... To have pushed it [the war] to a conclusion would have required more trained divisions and more supporting air and naval forces, would have incurred heavy casualties and would have necessitated lifting our self-imposed ban on attacks on the enemy sanctuary north of the Yalu.1

So argued General Clark some months after the signing of the armistice. What he was saying, in effect, was that there was no disposition in Washington toward undertaking the risks or the losses that military victory would have demanded during the year when he was in command. The limitations within which the Far East Command had to operate and the strength ceilings imposed upon the Eighth Army insured that no all-out effort against the enemy could be mounted. On the other hand, the Communist forces of Kim and Peng evidently labored under similar restrictions. They made no attempt to strike at the Japanese base area, giving it the same inviolability that the UNC granted Manchuria. At the front, Communists troops reacted strongly to attack, yet showed no signs of preparing to resume major offensive operations of their own. The rules were tacit, but nonetheless observed in mid-1952; this was a sparring match and not a fight for the championship.

Holding the Line

Across the front the two opponents were fairly evenly matched. Stretched from the west coast to the Taebaeks lay eight Chinese armies numbering an estimated 207,800 men and there were three North Korean corps anchoring the eastern end of the line with 83,000 troops. (See Map IV) Four U.S. Army divisions, the 1st Marine Division, the Commonwealth Division, and nine ROK divisions, totaling 247,554 soldiers, faced the enemy. In depth of manpower the Communists enjoyed a much greater advantage, for an estimated 422,000 Chinese, 185,300 North Koreans, and 10,000 Soviet or satellite troops disposed throughout North Korea supported the front-line forces. Thus, the 617,300 enemy troops in the immediate and general reserve plus the 290,800 on the firing line formed an estimated grand total of 908,100 Communist soldiers in North Korea on 1 May 1952.2 The average strength of UNC forces in South Korea during May was a little less than 800,000.3

The presentation of the package proposal in late April occasioned no interruption in the general pattern of operations at the front. Characterized by patrols, probes, raids, and limitedobjective attacks, the active defense generated only a low level of ground action. It was a contest of light jabs and feints with neither side attempting to sting the other into a violent, large-scale reaction.4

Since the lull on the battlefield imposed no severe strain upon the Eighth Army's combat troops, Van Fleet instructed his corps commanders in midMay to take full advantage of the respite to improve their defensive positions. Noting that many of the present deficiencies stemmed from the haste in planning and setting up the installations, he ordered special attention to be given to relocating bunkers below the topographical crest of hills, to resiting automatic weapons to obtain maximum grazing and flanking fires, and to strengthening bunkers to withstand light artillery and mortar fire. In addition, he wanted more tactical wire laid down and increased consideration devoted to the problem of draining communications trenches and bunkers before the rainy season arrived.5

Intelligence reports indicated that the enemy was carrying out similar action. Although prisoner of war interrogations revealed no Communist preparations for an imminent offensive, the enemy was engaged in improving the quality of his bunkers, planting mines, and stringing more barbed wire. The enemy defensive positions in many places extended twenty miles to the rear with adequate lines of communication.6

Perhaps more significant was the steady growth of enemy artillery firepower during the spring of 1952. From a total of 710 active pieces in April the enemy by June increased the number along the front to 884. The chief mission of the Communist artillery was to provide close support for the infantry on offense and defense and gradually enemy fire had become more accurate. Using eight to ten pieces, enemy massedfire techniques also improved. The Communists employed deceptive measures such as the firing of alternate, widely spaced guns, numerous firing positions, and a number of roving guns to make the task of accurate location of pieces more difficult for UNC units. By moving his artillery frequently and not concentrating the guns for long in any one sector, the enemy hindered effective counterbattery fire by the U.N. Command. Intelligence estimated that the Communists had about 500 prepared positions opposite the ROK II Corps alone in Maya Also impressive was the steady climb in the number of rounds directed at UNC positions. From a daily average of 2,388 rounds in April, the enemy almost tripled his fire in June to 6,843 rounds a day.8 The increase in ammunition fired demonstrated that the enemy had over a period of months gradually increased his forward supply levels.

To counteract the mounting effect of Communist artillery fire, Clark investigated the feasibility of utilizing two 280-mm. battalions, then being organized in the United States, to provide the Eighth Army with more firepower and longerrange weapons. Unfortunately these battalions would not be available until the end of 1952 and the joint Chiefs were loath to make a definite commitment so far in advance.9

The enemy was not alone in improving his artillery techniques during the spring. As the Communists conducted a series of nightly probes in the ROK 1st Division sector in May, the troops began to practice a ruse designed to inflict heavier enemy casualties. When the Chinese attacked, the ROK soldiers resisted for five to ten minutes, then withdrew slightly. After giving the enemy time to occupy the evacuated positions, artillery, previously zeroed in on the outposts, opened up. Within a half hour to an hour the Chinese usually withdrew and although the forces involved were seldom large, enemy losses were comparatively high.10

Old Baldy

Operations along the Eighth Army front during May were confined to smallscale actions that were quickly broken off by both sides when the exchanges threatened to grow to larger proportions. (Map 4) In early June, however, the tempo began to pick up.

The U.S. 45th Division of the I Corps manned main line of resistance positions from Hill 281, five miles northeast of Ch'orwon, to the village of Togun-gol, about eleven miles east of Ch'orwon. Except for Hill 281, all of the 45th Division front lines lay south of the Yokkokch'on which meandered through a rice paddy valley overlooked by lowlying, forested hills. Elements of the CCF 38th and 39th Armies controlled the dominant terrain to the north and in many cases were close enough to the 45th Division's main lines to enjoy excellent observation of the division's activities and to have convenient bases for dispatching their nightly raids and probes. The enemy's advantages became a matter of concern to Maj. Gen. David L. Ruffner when he assumed command of the division in late May, for they pointed up the lack of a strong outpost line of resistance. If the 45th Division could establish a chain of strong outposts across its front, it could deny enemy observers the use of much of the surrounding terrain dominated by the outposts and could also provide additional defensive depth to the division's lines.

Map 4. The Old Baldy Area

In early June General Ruffner and his staff selected eleven outpost sites situated at strategic locations in front of the division and decided that these sites would be taken and occupied on a 24-hour basis beginning on the night of 6 June. A twelfth objective would be raided and the enemy positions destroyed later during the two-phase operation, which was to be called COUNTER.11 Anticipating that the enemy might react quickly and strongly to the UNC move, Ruffner instructed his regimental commanders to carry out the operations after dark and to follow up immediately with sufficient reinforcements to fortify the outposts before daybreak.

The 279th Infantry Regiment, under Col. Preston J. C. Murphy, held the eastern half of the divisional front, and would take and hold objectives 1-6 and the 180th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Lt. Col. Ellis B. Ritchie, would seize and occupy objectives 7, 9, 10, and 11. Objective 8, known as Outpost EERIE, would be taken at a later date.12

Opposing the 45th Division from east to west were elements of the 338th and 339th Regiments, 113th Division, CCF 38th Army; 350th and 349th Regiments, 117th Division, CCF 39th Army; and the 344th Regiment, 115th Division, CCF 39th Army. The other infantry components of the 113th, 115th, and 117th Divisions were in reserve, as was the 116th Division, CCF 39th Army. The Chinese had over ten battalions of artillery positioned along the front in direct or general support roles.13

Several air strikes on known enemy strongpoints close to the outpost objectives took place during the daylight hours of 6 June. Then, after dark, Murphy and Ritchie sent out their units, ranging from a squad to almost a company, to take possession of the outposts. Evidently the enemy had not anticipated the operation, for the attack units encountered little opposition except at Outpost 10 on Hill 255 and Outpost 11 on Hill 266. The former, which was to become better known as Porkchop Hill, was taken by two platoons from I Company, 18oth Infantry, after a 55-minute fire fight with two Chinese platoons. On Hill 266, which had won the name of Old Baldy when artillery and mortar fire destroyed the trees on its crest, two squads from A Company, 180th Infantry, exchanged small arms and automatic weapons fire with two enemy squads, then withdrew and directed artillery fire upon the Chinese.

Pfc. James Ortega, a forward observer for the 171st Field Artillery Battalion, jumped into a trench and directed the artillery concentration which pounded the top of the hill with 500 rounds. When the artillery ceased, the men from A Company again probed the enemy's positions. Meeting intense fire, M/Sgt. John O. White took a squad, reinforced by a BAR and machine gun, and made a sweep to the rear of the enemy. "We saw a group of soldiers and thought they were our own men at first," he later reported. "We advanced to within 25 feet of them when we heard Chinese voices. Then we opened up and saw five men run out and get hit." As the enemy resistance crumbled, the infantrymen from A Company pushed their way toward the crest of Old Baldy. Enemy artillery immediately began to come in. "There were no bunkers or trenches to get into," M/Sgt. Gerald Marlin related afterward," so we started digging while the shells burst all around us. I almost crawled into my helmet." Despite the enemy fire, the A Company squads hung on and took possession of Old Baldy shortly after midnight.14

Once the outposts were seized, the task of organizing them defensively got under way. Aided by Korean Service Corps personnel the men of the 279th and 180th Infantry Regiments brought in construction and fortification materials and worked through the night. They built bunkers with overhead protection so that their own artillery could use proximity fuze shells when an enemy attack drew close to the outpost. They ringed the outposts with barbed wire and placed mines along the avenues of approach which were also covered by automatic weapons. Whenever possible, they sited their machine guns and recoilless rifles in positions where they could provide support to adjacent outposts. Signal personnel set up communications to the rear and laterally to other outposts by radio and wire and porters brought in stockpiles of ammunition. Back on the main line of resistance, infantry, tank, and artillery support weapons had drawn up fire plans to furnish the outposts with protective fires and a prebriefed reinforcing element was prepared to go to the immediate assistance of each outpost in the event of enemy attack. By morning the new 24-hour outposts were ready to withstand counterattacks, and garrison forces of from 18 to 44 men were left behind as the bulk of the forces from the 279th and 180th Infantry Regiments withdrew to the main line of resistance.15

Chinese probes and attacks on the outposts during the next few days met with no success despite an increase in their artillery and mortar support. At Porkchop Hill the outposts of the 180th Infantry Regiment repulsed several enemy drives of up to a company in strength.

On 11 June General Ruffner directed that the second phase of Plan COUNTER be carried out the following day. While two platoons of the 245th Tank Battalion mounted a diversionary raid along the Yokkok-ch'on valley from Chut'oso westward to the town of Orijong, the 180th Infantry would use up to three rifle companies to seize and hold Outpost 8 (EERIE) and to destroy enemy installations in the vicinity of the town of Pokkae (Objective A).16

Two platoons from B Company, 245th Tank Battalion, under the command of 1st Lt. Eugene S. Kastner, launched the raid toward Orijong at 0600 and ran into difficulty. Six tanks were disabled by enemy mines en route, but the remainder fired at enemy bunkers and gun positions on the hill mass west of Orijong and then withdrew. Five of the disabled tanks were later recovered.17 In the meantime, K Company, 180th Infantry, under Capt. Richard J. Shaw, and one platoon of the regimental tank company moved north to the Pokkae area and engaged the enemy. The infantry closed in to hand grenade range, but found that the Chinese had honeycombed the heights east of the town with bunkers, trenches, and tunnels. Since there was little hope of penetrating and destroying the strong enemy installations on the hill, the raiding party broke contact and returned to the main line of resistance. Losses were light, with four men wounded and one tank disabled for the raiders, while the enemy suffered an estimated sixty-five casualties.18

After an air strike by Fifth Air Force fighter planes and an artillery and mortar barrage on EERIE, E and F Companies, 18oth Infantry, under 1st Lt. John D. Scandling and Capt. Jack M. Tiller, respectively, attacked from the southeast against heavy small arms, automatic weapon, artillery, and mortar fire and took the objective. G Company, 18oth Infantry, quickly moved up under the command of 1st Lt. Richard M. Lee to reinforce its sister companies before the expected enemy counterattack took place. The Chinese came back strongly and casualties were heavy on both sides, but the 18oth Infantry units hung on tenaciously until the enemy broke off the engagement. During the next two days the Chinese attempted fruitlessly to drive the 45th Division from EERIE.19

From a Chinese document captured later came an entirely different account of the action in this section:

From 0500 hours on 12 June 52, the enemy [the UNC] fought against us on Hill 190.8 and battled heroically for 5 days. The result of the fighting on the 16th was 2300 enemy casualties and 9 tanks destroyed. We had an honorable victory as above.

At 0550 hours on 12 June 52, enemy attacked our positions on Hill 190.8 with a force of 7 companies and 74 tanks which were covered by airplanes against our 1st Co, 50th Co.

We met the attackers and killed and injured them. At 0900 hours, they finally occupied Hill 190.8. About 56 squads of the 1st Co., the defending force on Hill 190.8 began tunnel warfare. At 2237 hours, the 3d Co. counterattacked against the enemy under cover of heavy artillery barrage and reoccupied the position. Casualties inflicted against the enemy amounted to 772 personnel and 8 tanks destroyed.

In the dawn of the 13th the enemy attacked our 1st Co. positions on the 1st, 2d and unknown hill with a force of 5 companies and 15 tanks which were given air cover by 12 planes. The intense battle continued until 1500 hours. We counterattacked with the 2d CO, 5th Co and the 1st Co. Enemy casualties were 600 personnel and 2 tanks destroyed.

For 2 days from 14th to 15th, the enemy attacked the 2d unknown hill continuously but the enemy was repulsed. The enemy casualties were 56 personnel.

On this night of the 15th, our 50th Co and 51st Co counterattacked in large force against the enemy who occupied both of the hills by attacking with a force of 7 companies which were covered by artillery fire and tanks. After bombarding the positions for 35 minutes, we made a sudden attack upon them. At approximately 0130 hours on June 16th, the battle ended victoriously.

An estimated enemy force of over 1000 men who attacked both of the hills were annihilated.

Meanwhile, in another spot, 4 squads making up the main force bravely resisted the enemies in tunnel warfare and achieved victory.20

The Chinese resort to tunnel warfare led to the sealing of tunnel entrances by the UNC troops. According to later prisoner of war interrogations, Chinese officers had killed a number of soldiers in the tunnels because the latter had wished to dig their way out and surrender to the U.N. Command. After the 45th Division forces secured the hills, they opened the tunnels and captured the Chinese who were still alive and willing to give up.21

On 16 June the 179th Infantry Regiment, commanded by Lt. Col. Joseph C. Sandlin, relieved the 180th on the line and took over the outpost positions on Old Baldy, Porkchop, and EERIE. Enemy attacks during the next ten days ranged from platoon to battalion strength, demonstrating the Communist determination to eliminate these outposts. By the same token the 45th Division's repulse of the many enemy efforts along this line attested to the division's equal determination not to be dislodged.22

The contest for Old Baldy became very heated on 26 June. The hill was the high point of an east-west ridge and dominated the terrain to the north, west, and south. Almost 1,000 feet west of the crest the Chinese had established positions that posed a constant threat to the 45th Division outpost and the 179th Infantry Regiment's troops in the area. Colonel Sandlin decided to destroy the enemy strongpoints. Early in the morning the 179th Infantry Regiment vacated its outpost on Old Baldy to permit air strikes and artillery and mortar barrages to be placed on the enemy positions. Eight fighter-bombers from the Fifth Air Force dropped bombs and loosed rockets and machine gun fire; then 45th Division artillery and mortar units began to lay concentrations on the enemy strongpoints.

C Company (Reinforced), 179th Infantry, under 1st Lt. John B. Blount, and F Company, 18oth Infantry, commanded by Captain Tiller, which was attached to the 1 79th, attacked after the artillery and mortar fire. With C Company moving in from the left and F Company, supported by a tank, coming in from the right finger of Old Baldy, the assault forces soon ran into heavy small arms and automatic weapons fire from the two Chinese companies who comprised the defense force. After an hour of fighting the Chinese suddenly pulled back and directed artillery and mortar fire upon the attacking units. When the fire ceased, the enemy quickly came back and closed with the men of C and F Companies in the trenches. A Company, 179th Infantry, under 1st Lt. George L. Vaughn, came up to reinforce the attack during the afternoon, for the enemy machine guns were making it difficult for men of C and F Companies to move over the crest of the hill. The attack force regrouped, with F Company taking over the holding of the left and right fingers of Old Baldy, C Company holding the old Outpost 11 position, and A Company working its way around the right flank of the enemy defenders. For two hours the battle continued as the Chinese used hand grenades and machine guns to repel each attempt to drive them from their positions. Late in the day two tanks lumbered up the hill to help reduce the enemy strongpoints; one turned over and the second threw a track, but they managed to inflict some damage before they were put out of action. Gradually the enemy evacuated his positions and the 179th was able to send engineers and several more tanks up to the crest.23

During the night of 26 June and the following day the three companies dug in to consolidate their defense positions on Old Baldy. On the afternoon of 27 June L Company, 179th Infantry, under 1st Lt. William T. Moroney, took over defense of the crest and F Company, 18oth Infantry, moved back to a supporting position. C Company and elements of A Company held the ground northwest of the crest which had been won from the enemy.

When night fell, enemy activity around Old Baldy increased. Mortar and artillery fire began to come in on the 179th Infantry Regiment's positions and enemy flares warned that the Chinese were on the move. At 2200 hours the enemy struck the defenders of L Company from the northeast and southwest. An estimated reinforced battalion pressed on toward the crest until it met a circle of defensive fire. From the main line of resistance, artillery, mortar, tank, and infantry weapons covered enemy avenues of approach. L Company added its small arms, automatic weapons, and hand grenades to the circle which kept the Chinese at bay. Unable to penetrate the ring, the enemy withdrew and regrouped at midnight.

The second and third attacks followed the same pattern. Each lasted over an hour during the early morning of 28 June and each time the enemy failed to break through the wall of defensive fires. After suffering casualties estimated at between 250 and 325 men, the Chinese broke off the fight. The 179th Infantry reported six men killed and sixty-one wounded during the. three engagements.24

Late in the evening of 28 June, the Chinese artillery and mortar fire on Old Baldy signaled the approach of another attack. Four enemy squads reconnoitered the 179th positions at 2200 hours, exchanging automatic weapons and small arms fire. About an hour later the main assault began with a force estimated at two reinforced battalions moving in from the northeast and northwest behind a very heavy artillery and mortar barrage. This time the Chinese penetrated the perimeter and hand-tohand fighting broke out. Shortly after midnight a UNC flare plane began to illuminate the battle area and the defensive fires from the main line of resistance, coupled with the steady stream of small arms and automatic weapons fire from the three companies of the 179th on the hill, became more effective. By 0100 on 29 June the Chinese disengaged to the north, having suffered losses estimated at close to 800 men. In return the enemy had fired over 4,000 rounds of artillery and mortar fire and the 179th Infantry had suffered 43 casualties, including 8 killed in action.25

As June ended, the 45th Division, despite the lack of combat experience of many of its troops, had acquitted itself well on the battlefield. In the fight for the outposts the division had withstood more than twenty Chinese counterattacks and inflicted an estimated 3,500 casualties on the enemy. It had also won a commendation from Van Fleet.26 The enemy made one more attempt to wrest control of Old Baldy from the 45th Division's possession on the night of 3-4 July. Three separate attacks-the last in battalion strength-met the same fate as their predecessors as the concentration of defensive firepower first blunted and then forced the Chinese to desist in their assaults.27 The thorough manner in which the division had organized the defense of the outposts and the skill with which it had used its positions during the fighting were a testimonial to the leadership on all levels and to the courage of its troops.

The 45th Division was less successful in another field. On 8 June Clark directed Van Fleet to prepare a plan for capturing Chinese prisoners in the Ch'orwon area. Clark wanted to discover the identity of the enemy forces in that sector and learn more of their role. Several days later Van Fleet submitted two plans, one envisaging the use of a regiment from the ROK 9th Division and the second a reinforced battalion from the 45th Division. The latter contemplated tank, air, and artillery support and the 45th Division was authorized to carry it out as quickly as possible.28

Early on 22 June, the 2d Battalion, 279th Infantry Regiment, set out to capture enemy prisoners on the north bank of the Yokkok-ch'on. The difficulty encountered by the battalion in taking Chinese prisoners was later succinctly related by the Eighth Army historian: "The raiding party had destroyed enemy positions, inflicted numerous casualties and captured three prisoners. The prisoners, however, were not interrogated: two of them died of wounds inflicted by enemy troops as the prisoners were being brought to the MLR and the third was killed when he attempted to throw a grenade after being captured." Despite other efforts on a smaller scale to take prisoners, the 279th Regiment's total bag for the month of June was but six prisoners.29

The experience of the 279th Regiment was by no means isolated. In combat the Communist soldier could be killed or wounded, but seldom taken prisoner during this period. The fact that General Ruffner issued a letter to his troops in June providing for a special rest and recuperation leave in Japan to any soldier capturing an enemy prisoner amply demonstrated the problem.30

Nevertheless, in July Clark approved another attempt, this time by the ROK 11th Division of the ROK I Corps, to capture North Korean prisoners. BUCKSHOT 16, as the plan was dubbed, sent a reinforced battalion into the sector west of the Nam River on 8 July. The battalion suffered casualties of 33 killed, 157 wounded, and 36 missing as against estimated enemy losses of 90 killed and 82 wounded. Not a prisoner was taken.31

The results of these abortive raids convinced Clark that the UNC losses in their efforts to take prisoners were not worthwhile. On 19 July he turned down Van Fleet's request for a similar operation in the 1st Commonwealth Division area. If the Eighth Army did not feel an enemy attack was imminent, Clark did not think the high UNC casualty rate incurred in such raids was warranted.32

For General Van Fleet, who may have hoped that the change-over in commanders from Ridgway to Clark might result in less restriction upon his activity along the front, June and July may have been disillusioning. Van Fleet's plans for the IX U.S. Corps to advance to new positions north of P'yonggang and secure control of all the Iron Triangle met with little enthusiasm from Clark in late June. To the Eighth Army commander's arguments that the operation would provide intelligence of enemy positions, give the UNC troops experience, destroy enemy stockpiles, and utilize U.S. firepower and ROK Army mobility, Clark listed corresponding disadvantages. The possibility of adverse effects upon the negotiations, the numbers of friendly casualties involved, the lack of UNC reserves if a heavy enemy counterattack followed, and the unprofitable nature of an advance beyond P'yonggang without further exploitation, Clark told Van Fleet in disapproving the plan, exceeded the advantages.33 It was evident that the new commander would be as reluctant as Ridgway had been to step up the pace of the ground war merely to gain real estate.

Behind Clark's disinclination to approve even limited objective attacks lay his realization that the enemy ground and air strength had almost doubled since the initiation of negotiations. The Communists' divisions along the front were at full combat strength and their air forces based in Manchuria now numbered about 2,00o aircraft of which approximately half were jets. In addition, the enemy had an increased number of rocket launchers and field artillery, around 400 tanks, an improved supply situation, and stronger defense lines. Under these circumstances, Clark felt that the best way to punish the Communists lay in letting the enemy take the offensive and not vice versa.34

Thus it was not surprising that the Far East commander became disturbed over Van Fleet's instructions to his corps commanders on 18 July. Van Fleet told them there were indications that, in some sectors, the enemy had shifted forces and evacuated a number of forward positions. When this occurred, he desired contact with the enemy maintained and the evacuated positions to be occupied for at least twenty-four hours. Commanders should be ready for a violent Communist reaction, Van Fleet continued, and complete fire plans should be made and communications insured.35 As soon as Clark heard of this directive, he instructed his staff to determine whether the Eighth Army should be allowed to carry out such a procedure. His own reaction was that all plans for raids by units of battalion size or larger should be approved by the Far East Command first.36 In late July, he told his staff that he intended to discourage attacks against hills like Old Baldy in the future. Clark wanted the U.N. Command to confine itself to patrolling and let the enemy do the attacking.37

The concern of the United Nations commander over the merit in seizing terrain features like Old Baldy was caused by the resurgence of activity in that area in mid-July. The enemy had not attempted to take the hill again until the U.S. 2d Division relieved the 45th Division during midJuly. All of the Eighth Army's corps followed a policy of rotating their divisions periodically on the line and the 45th had spent over six months at the front. The Chinese took advantage of the relief as they mounted two attacks on the night of 17-18 July in strengths exceeding a reinforced battalion. Through quick reinforcement of the Old Baldy outpost and heavy closedefensive fires, E and F Companies, 23d Infantry Regiment, who were defending the hill managed to repel the first enemy assault. But the second won a foothold on the slopes which the enemy reinforced and then exploited. Chinese artillery and mortar fire became very intense; then the enemy infantry followed up swiftly and seized the crest. Counterattacks by the 23d Regiment supported by air strikes and artillery and mortar fire, did not succeed in driving the Chinese from the newly won positions. By 2o July the 2d Division elements had regained only a portion of the east finger of Old Baldy. The onset of the rainy season made operations exceedingly difficult to carry out during the rest of the month.38

As the torrential downpours converted the Korean battleground into a morass in the last week of July, the U.N. Command counted its losses on Old Baldy during the month. Through z I July the tally showed 39 killed, 234 wounded, and 84 missing for the UNC and an estimated 1,093 killed and wounded for the Chinese.39 Although the totals were not unusually high considering the intensity of the fighting and the artillery exchanges, it is not difficult to understand General Clark's concern over the casualties suffered in the fight for one more hill.

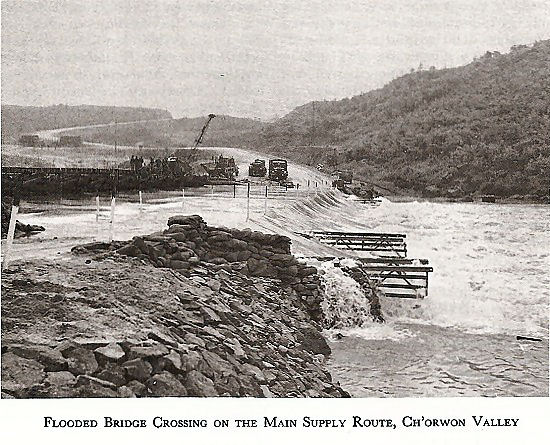

Six consecutive days of heavy rain flooded the streams and rivers and swept away bridges. As the water seeped into the ground, landslides began and roads were blocked or washed away. The task of resupply became a distinct challenge to surmount nature's obstacles.40 Since the Communists had to cope with similar problems both sides devoted their main efforts against the common enemy and tactical operations were strictly limited.

When the rain eased off at the end of July, the 23d Infantry Regiment again sought to secure complete control of Old Baldy. Since the Chinese had an estimated two platoons on the crest, the 23d sent two reinforced companies up the slopes after artillery and mortar preparatory fires on the enemy positions. Edging toward the Chinese defenses, the 2d Division forces used small arms fire and hand grenades as they reached the enemy trenches. After bitter hand-to-hand combat, the two companies finally gained the crest early on 1 August and dug in to prepare for the customary counterattack, Two hundred flares were distributed around the friendly positions and fortytwo air sorties were flown during the day in support. That night the enemy sent first mortar, then artillery, fire at the crest, dropping an estimated 2,500 rounds on the 23d Regiment elements. But counterattacks were driven off.

Mines, bunkers, and additional wire helped to strengthen the UNC hold on Old Baldy on 2 August and extremely heavy and effective artillery fire broke up another enemy assault on 4 August. For the remainder of the month, the Chinese refrained from further attempts on Old Baldy.41

In mid-September, the enemy employed two reinforced companies, supported by artillery and mortar fire and two tanks, in another desperate effort to regain control of the controversial hill. Infiltrating groups fought their way into 2d Division positions on 18 September and hand-tohand fighting broke out. Under the pressure of the assault, the defending forces withdrew more than 400 yards from the crest and regrouped. Elements of the 38th Infantry Regiment tried unsuccessfully to envelop the Chinese defenders on 20 September, but the following day a platoon of tanks moved up and supported a second two-pronged drive that forced the enemy to withdraw once more.42

The fight for Old Baldy was typical of the battles waged during the summer and fall of 1952, a savagely contested, seemingly endless struggle for control of another hill. And there seemed to be little hope that there would be any significant change in the pattern.

Up the Hill, Down the Hill

The renewal of activity at the front and the lack of great expectations from Panmunjom produced several intelligence estimates during the summer of 1952 that were discouraging in tone. In Washington and in the Far East the planners and intelligence experts foresaw little change in the tenor of the war. The enemy, in his estimate, was strongly entrenched, had expanded his air and ground strength, and showed no signs of accepting an armistice on UNC terms. On the other hand, the Communists evidenced no disposition to return to large-scale fighting and seemed content to rest on their increased defensive strength, confident of their ability to wait out the UNC. Unless the United Nations Command mounted a major offensive and broadened the geographical limits of the war, the intelligence officials did not believe that sufficient military pressure could be applied upon the enemy to bring about a swift conclusion to the war. Since there was small likelihood of securing substantial troop augmentations for the U.N. Command that would have to precede any major offensive, or of gaining approval of more than limited objective attacks, the prospects of a dramatic shift in the tempo of the conflict appeared remote. As long as the Communists made no attempt to alter the status quo, the outlook was for more of the same type of hill warfare that had characterized the second year of the war.43

Although the fight for Old Baldy had received the bulk of the publicity during the summer months, sporadic excitement had flared up in other sectors. In early July on the U.S. I Corps front the ROK 1st Division had carried out a successful battalion raid against Chinese positions south of Sangnyong-ni, approximately seventeen miles southeast of Ch'orwon. Two days later, on 3 July, the 1st Marine Division sent a company raiding party against the Chinese positions at Punji-ri, three and a half miles northeast of Panmunjom. The marines destroyed enemy troops and bunkers, then withdrew to the main line of resistance.44

Other forays were not quite so fortunate: On the ROK II Corps front, the ROK Capital Division's attempts to take over Communist hill positions near Yulsa-ri, fifteen miles northeast of Kumhwa, were repulsed. The ROK 5th Division, ROK I Corps, also met determined North Korean resistance when it tried to drive the enemy from a hill close to Oemyon, seven miles south of Kosong on the east coast. The North Koreans mounted a retaliatory attack on to July against a nearby hill controlled by the ROK 5th Division and held it for four days before they were forced to withdraw.45

In August the limited ground pressure applied by the UNC to help its negotiators at Panmunjom led to the outbreak of several bitter, small-scale battles for favorable terrain features. Four miles east of Panmunjom elements of the 1st Marine Division on g August lost an outpost to the Chinese on Hill 58. The position changed hands five times during the next two days, but the enemy eventually gained the upper hand. The marines then shifted their attack to nearby Hill 122 which dominated Hill 58 and caught the enemy unawares. From 12 to 14 August a reinforced Marine company turned back Chinese counterattacks of up to a battalion in strength. Despite the failures of these attempts, the enemy tried again on 16 and 25 August, sustaining heavy casualties and no success in its efforts to drive off the marines. Hill 122 won a proud name in these encounters- Bunker Hill.46

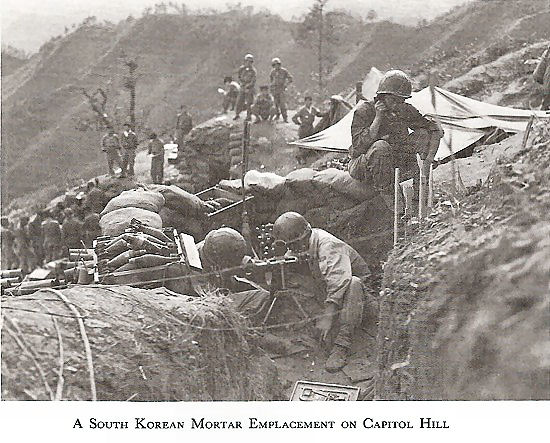

About seven miles east of Kumsong, on the ROK II Corps front, the ROK Capital Division became embroiled in another fierce struggle. Overlooking the division's positions stood a hill, later to be known as Capitol Hill, where the enemy maintained outposts. On the night of 5-6 August elements of the Capital Division infiltrated and captured two of the outposts. The response was immediate. Building up from a reinforced platoon to two companies, the Communists hurled their troops against the ROK's manning the positions. For the next four days control seesawed back and forth, but the ROK 26th Regiment stubbornly fought back and drove the enemy off. On 10 August, the Communists broke off the attack, having suffered casualties of 369 dead, an additional 450 estimated dead, and 190 wounded. The ROK 26th Regiment lost 48 killed and 150 wounded during the action and won a commendation from Van Fleet for its courageous defense.47

While the negotiators at Panmunjom were meeting once a week in August and the Korean rainy season continued, activity along the front eased. Then in early September the weather improved and the Chinese hit Capitol Hill again. They gained possession of the crest temporarily until the ROK 26th Regiment joined forces with the ROK 1st Regiment to retake the hill on 9 September. Up to three enemy companies sought to fight their way back to the top at a time, but the ROK units refused to be dislodged again.48

Two miles west of Capitol Hill lay a long, fingershaped ridge, which unsurprisingly soon came to be known as Finger Ridge. Held as an outpost by the Cavalry Regiment of the Capital Division, the position was overrun by the enemy on 6 September- the same day it launched its assault on Capitol Hill. The Cavalry Regiment struck back; but had to withdraw as the enemy increased his defending forces. Up the hill, down the hill went friendly and hostile forces as they wrestled for control during the rest of September and well into October. By mid-October, Finger Ridge was once more in the hands of the Capital Division.49

After the heavy rains of August came to an end, the Chinese renewed the Battle of Bunker Hill (Hill 122 in the 1st Marine Division sector. On 5 September the Marine positions were first subjected to a heavy artillery concentration and then to an assault by an enemy battalion. For two hours the contest for the heights swung back and forth, but the marines would not give in. Finally the Chinese began to disengage. Over the next ten days the enemy sent a number of raids and harassing expeditions against Bunker Hill with the marines successfully defending their outposts on each occasion.50

The Chinese probing for soft spots in the UNC lines continued in mid-September. In the U.S. 3d Infantry Division sector of the JAMESTOWN line there were a series of outposts manned by forces varying from a squad to a company in strength on the low-lying hills in front of the main line of resistance. One of these was Outpost KELLY, situated three miles south of Kyeho-dong and about one mile west of the double horseshoe bend of the Imjin River. On 17 September C Company, under the operational control of the 2d Battalion, 65th Infantry, defended KELLY.51

Facing the 65th Regiment in the area around KELLY were the 2d and 3d Battalions, 348th Regiment, 116th Division, CCF 39th Army. There had been an increase in the number and aggressiveness of enemy' patrols in the entire 65th Regiment sector during September and also an increase in the frequency of enemy mortar fire. These signs usually heralded an impending enemy attack.

On the night of 17 September an estimated enemy company from the 2d Battalion, 348th Regiment, probed Outpost KELLY'S defenses. When C Company requested reinforcements to fight off this probe, Col. Juan C. Cordero, commanding officer of the 65th, ordered B Company to relieve its sister company on KELLY. B Company took over KELLY and passed to the operational control of the 2d Battalion commander, Lt. Col. Carlos BetancesRamirez, early in the morning of 18 September.

The enemy mortar fire on KELLY continued throughout the day and 1st Lt. William F. Nelson, B Company commander, in the early evening requested that the artillery supporting his position be prepared to fire variable time fuze shells in the event of an enemy attack. Less than an hour after his request an estimated two companies from the 2d Battalion, 348th Regiment, attacked the outpost from the southwest, northwest, and northeast. The northeast attack evidently surprised Lieutenant Nelson and leis men, for the Chinese swept across the hill and took the B Company machine gun position on the northwest corner of the hill from the rear. Killing the gunner, the enemy advanced along the trenches and closed in handto-hand combat. The sergeant in charge of the machine gun position managed to escape after he sustained arm injuries in the fight. Communications between KELLY and battalion headquarters were cut off and the situation was very confused by midnight, but reports of Chinese herding American prisoners down the slopes of KELLY indicated that the position had been lost. There were also reports that some of the Chinese were wearing U.S. uniforms, but it was not clear whether the enemy had donned the American clothes before or after the attack.

To find out whether the enemy intended to occupy the outpost, the regimental intelligence officer ordered the 2d Battalion to send a platoon as quickly as possible from E Company to reconnoiter the hill. The patrol cleared the main line of resistance shortly before daylight on the 19th, but soon ran into machine gun and rifle grenade fire as it advanced up the hill.

Convinced that the Chinese planned to remain, Colonel Cordero made an assessment of the situation. The heavy mortar fire and the attack that had followed had badly depleted B Company, although there might be some remnants of the company still on the hill. He assumed that the enemy now held the position with small arms, light machine guns, and light mortars. There was a waist-deep, circular trench that ringed the military crest of the hill completely and four bunkers. At the base of the hill, on the approaches, the Chinese had established combat outposts of squad size.

Colonel Betances, the 2d Battalion commander, ordered two platoons from E Company to advance on KELLY on the morning of 20 September. By late afternoon one platoon under the company commander, 1st Lt. Harold L. Gensemer, had fought its way to the top. The second was still on the porters' trail moving forward slowly. The Chinese, however, had no intention of surrendering possession of KELLY for they quickly sent reinforcements to bolster their defending forces. Lieutenant Gensemer's platoon began to take casualties from the small arms, machine gun, and mortar fire, and the second platoon was forced to fall back as it encountered similar enemy opposition on its way to the crest. Faced with the Chinese determination to hang on to the outpost and the mounting casualty list, the two platoons withdrew to the main line of resistance.52

In the meantime, the 1st Battalion, commanded by Maj. Albert C. Davies, prepared to counterattack through the 2d Battalion's positions. During the evening of 20 September, A Company, under 1st Lt. St. Clair Streett, Jr., moved forward to take up the attack from the south and C Company, under 1st Lt. Robert E. Stevens, advanced to the base of the hill on which KELLY was located. The enemy mortar and artillery became very heavy as the men crossed the valley floor en route to the hill approaches.

As the two companies began their ascent, B Company moved forward toward the outpost line to support the attack. Mortar fire came in swiftly and with deadly effect as casualties cut the strength of B Company to twenty-six men and forced the cancellation of the company mission.

The Chinese small arms, machine gun, and mortar fire was also taking its toll of A and C Companies. In addition, the Chinese used timefuzed artillery fire as the 1st Battalion troops edged their way to the top. The airbursts over the heads of A and C Company were demoralizing and caused panic. Lieutenant Streett had to fall back and reorganize A Company, while Lieutenant Stevens clung to a finger of the hill with two platoons. The forces under Streett and Stevens totaled about 6o men each at this juncture, while the enemy had an estimated 100 men on the hill and was reinforcing freely.

A UNC artillery barrage pounded the Chinese positions on KELLY early in the morning of 21 September. But when the remnants of A and C Companies tried to close in on the Chinese positions, the enemy again met them with small arms and hand grenades. Two squads from C Company almost reached the crest of KELLY shortly before noon only to receive mortar concentrations that forced them to fall back to the trenches. No sooner had the enemy mortar fire ceased when the Chinese counterattacked and forced C Company to pull out completely. In the early afternoon Major Davies ordered A, B, and C Companies to return to their company areas. They had suffered over seventy casualties in the fight for KELLY. That night the 1st Battalion relieved the 3d Battalion and the action around KELLY slowed down for several days.

As the 3d Battalion took over responsibility for the 1st Battalion positions, Lt. Col. Lloyd E. Wills, who had assumed command of the 3d Battalion on 2o September, and his staff, drew up an attack plan to recapture KELLY. Since the previous efforts by forces ranging from one to four platoons had failed to dislodge the enemy, Colonel Wills received approval to use his three rifle companies. K Company, under Capt. William C. English, would attack from the east and L Company, under 1st Lt. Frederick Bogell, would come in from the west. 1st Lt. Ben W. Alpuerto's I Company would be the reserve.

At 0520 on 24 September the 105-mm. howitzers of the 58th Field Artillery Battalion, commanded by Lt. Col. Mario DeMaio, opened up on the Chinese positions on and around KELLY for thirty minutes. Meanwhile a platoon of tanks from the 64th Tank Battalion rumbled into position to support the 3d Battalion attack. Artillery and tanks sent 25,000 rounds against the Chinese in support of the attack. K and L Companies were in their attack positions by 0540 and launched their assault half an hour later. As Captain English and his K Company troops approached KELLY, the Chinese opened up with intense small arms, machine gun, artillery, and mortar fire and soon had K Company pinned down. The heavy enemy concentration of firepower and the growing list of casualties led to panic and confusion in the company. With control of the company disintegrating and the casualties mounting, English asked for permission to pull back and reorganize. Colonel Cordero at 0800 ordered that this request be denied and that the company continue its attack. Shortly thereafter contact with K Company was lost. The artillery forward observer managed to hold together ten men from the company, however, and Colonel Wills, the battalion commander, instructed him to continue the attack on KELLY with his small force.

On the western slopes of KELLY, L Company assaulted the Chinese positions at o635 hours. Despite heavy mortar fire, one squad reached the top at 0720 and quickly asked for tank fire. Clinging to the trenches on the south slope of KELLY, the L Company squad was unable to move forward against the stubborn enemy resistance. Chinese artillery and mortar fire continued to be very heavy.

Since contact with K Company had not been regained by 0800 hours, Colonel Cordero ordered I Company to move to the rear of Hill 105, 80o yards east of KELLY, and to prepare to take over K Company's zone. Lieutenant Alpuerto moved his men toward Hill 105, but the enemy artillery zeroed in on the company and scored several direct hits. The men began to scatter and drift back to the main line of resistance. Colonel Wills sent his S-3, Capt. Paul O. Engle, to help reorganize the company, since contact with Lieutenant Alpuerto had been lost after the enemy artillery concentrations had begun. Colonel Wills left at 0900 hours to take over the reorganization of both I and K Company stragglers as they returned to the main line of resistance without weapons or equipment.

With only the remnants of L Company still on KELLY, and the other two companies depleted and demorilized, the situation appeared grim. The two squads from L Company hung on to one of the trenches on the south slope and at 0920 hours Colonel Cordero ordered them to stay there at all costs.

When Colonel Wills finally regained contact with Lieutenant Alpuerto at 1000 hours, I Company had reorganized and had two platoons intact; the remainder of the company's whereabouts was unknown. Colonel Wills telephoned the assistant division commander, Brig. Gen. Charles L. Dasher, Jr., and informed him that the battalion had approximately two platoons available for combat. General Dasher told Wills to cease to attack and to continue the reorganization of the battalion, which had suffered 141 casualties in the action. By early afternoon the squads from L Company had been withdrawn and the stragglers reassembled. But the division commander, Maj. Gen. Robert L. Dulaney, decided that the battalion and the regiment should not resume the battle for KELLY. The 3d Battalion went into reserve positions on the night of 24 September and the 65th Regiment confined itself to routine patrolling until the ROK 1st Division relieved the 3d Division on 30 September.

During the action between 17 and 24 September for KELLY and the surrounding outposts, the 65th Regiment suffered casualties of approximately 350 men, or almost 10 percent of its actual strength. Yet the casualties alone do not serve to explain the weaknesses that arose when the regiment went on the offense. Colonel Cordero in his command report for the month attributed the poor performance of his combat units to the rotation program.

During the nine-month period JanuarySeptember 1952, Colonel Cordero stated, the regiment had rotated almost 8,800 men, including close to 1,500 noncommissioned officers. Only 435 noncommissioned officers had been received to replace the losses, and company commanders had been forced to assign inexperienced privates first class and privates to key positions in many rifle platoons. Out of an authorized strength of 811 noncommissioned officers in the upper three grades, the 65th Regiment had only 381 and many of the latter had been developed from recent replacements. The lack of experienced platoon sergeants and corporals had affected the combat efficiency of the regiment, Colonel Cordero went on, despite the high esprit de corps shown by the many Puerto Rican members of the regiment. In many cases, as soon as the company and platoon leaders became casualties, the inexperience and lack of depth at the combat company level became readily apparent. There was a failure to sustain the momentum of the attack and a tendency to become confused and disorganized after the leaders became casualties. Colonel Cordero recommended that his regiment be provided with a monthly quota of 400 replacements including a fair proportion of the upper three grades so that he could remedy this basic weakness.53

Although Colonel Cordero did not mention the language barrier, it should not be overlooked that the great majority of enlisted men in the regiment spoke only Spanish, creating a problem of communication between the continental English-speaking officers and the enlisted men from Puerto Rico.

On the other side of the coin had been the determination and skill with which the Chinese 348th Regiment had defended Outpost KELLY. The enemy had used his artillery, mortars, automatic weapons, and small arms fire extremely effectively and had sent in reinforcements liberally to blunt and turn back the 65th Regiment's attacks. Thus, the failure of the 65th Regiment to take KELLY could be attributed both to its personnel weaknesses and the enemy's strong performance and skill in using his weapons.54

The Battle for White Horse

Communist activity along the front increased in the early fall of 1952 as the enemy sought to improve his defensive positions before the onset of winter. The fight for Outpost KELLY was but one of several contests for hill positions waged by the Eighth Army. Perhaps one of the most dramatic came in early October in the U.S. IX Corps sector west of Ch'orwon.

On 3 October the Eighth Army learned through interrogation of a Chinese deserter that the enemy proposed to attack White Horse Hill (Hill 395), , which was five miles northwest of Ch'orwon on the ROK 9th Division front. White Horse was the crest of a forested hill mass that extended in a northwestsoutheast direction for about two miles. Overlooking the Yokkok-ch'on Valley, it dominated the western approaches to Ch'orwon. (Map 5) Loss of the hill would force the IX Corps to withdraw to the high ground south of the Yokkok-ch'on in the Ch'orwon area, would deny the IX Corps use of the Ch'orwon road net, and would open up the entire Ch'orwon area to enemy attack and penetration.55

Since other intelligence sources supported the prisoner's story, IX Corps reinforced the ROK 9th Division, under Maj. Gen. Kim Jong Oh, with additional tanks, artillery, rocket launchers, and antiaircraft weapons to be used in a ground role. General Kim stationed two battalions of infantry on the threatened hill and held a regiment plus a battalion in ready reserve. On the flanks of White Horse he positioned the tanks and antiaircraft guns to cover the valley approaches. Searchlights and flares were distributed to provide illumination at night and a flare plane was made available to supply additional light on call during the hours of darkness. From the Fifth Air Force came extra air strikes against enemy artillery positions adjacent to White Horse. As the hour of the attack approached, the ROK 9th and its attached units were well prepared.

Just before the Chinese began their advance on White Horse on 6 October, they opened the floodgates of the Pongnae-Ho Reservoir, which was located about seven miles north of the objective, evidently in the hope that the Yokkokch'on which ran between the ROK 9th and the U.S. 2d Division would rise sufficiently to block reinforcement during the critical period. Although the water level rose several feet, at no time did it present a tactical obstacle. But the Chinese did not rely upon nature alone. They threw a battalion-sized force at Hill 281 (Arrowhead), two miles southeast of White Horse across the valley, to pin down the French Battalion astride the hill and to keep the 2d Division occupied. Before the night was over six additional companies joined in the action. The French held firm and inflicted heavy casualties upon the attackers. Two later assaults on g and 12 October met with similar responses. As a diversion to the main attack on White Horse, Hill 281 proved effective but expensive.

In the meantime, two battalions of the 340th Regiment, 114th Division, CCF 38th Army, moved up to the northwest end of the White Horse Hill complex. After heavy artillery and mortar fire upon the ROK 9th Division positions on the heights, the Chinese tried three times to penetrate the ROK defenses. Each time they were hurled back by troops of the ROK Both Regiment, suffering an estimated 1,500 casualties the first night as against only boo for the defenders. Notwithstanding the heavy losses, the Chinese committed the remnants of the original two battalions and reinforced them with two fresh battalions from the same division the following day. Cutting off a ROK company outpost, the Chinese pressed on and forced the elements of the ROK Both Regiment to withdraw from the crest. Less than two hours after the loss of the peak, two battalions of the ROK 28th Regiment mounted a night attack that swept the enemy out of the old ROK positions. Again the enemy losses were heavy and a Chinese prisoner later related that many of the companies committed to the attack were reduced to less than twenty men after the second day of fighting.

By the third day Chinese diversionary attacks elsewhere along the corps front decreased and the main enemy effort concentrated on Hill 395. Chinese artillery and mortar fire averaged 4,500 rounds a day in support of the infantry assaults, and the enemy continued to assemble fresh troops to renew the battle. On 8 October two battalions from the 334th Regiment, 112th Division, and one from the 342d Regiment, 114th Division, relieved the depleted Chinese forces around White Horse. Elements of the 3¢2d fought their way to the crest during the afternoon, only to lose it to a ROK 28th Regiment counterattack that night.

Nothing daunted, the Chinese committed another battalion to the attack on the following day. General Kim, the ROK 9th Division commander, moved two battalions of his 29th Regiment over to Hill 395 to help the 28th Regiment. Throughout the day the battle seesawed as first one side controlled the peak, then the other. Early on 10 October, the 29th Regiment reported that it was in possession of the crest.

The UNC forces apparently were fortunate on g October, for a Chinese prisoner later related that Fifth Air Force planes had caught elements of the 335th Regiment, 112th Division, in an assembly area north of Hill 395, had inflicted heavy casualties upon the regiment, and had delayed its commitment to the attack.

By 10 October the pattern of the fighting was well established. Regardless of casualties, the enemy continued to send masses of infantry to take the objective. Evidently, once given a mission, Communist commanders adhered to it despite their losses. On White Horse, the Chinese kept funneling their combat troops into the northern attack approaches where Eighth Army artillery, tanks, and air power could wreak havoc. The enemy's determination to win White Horse made sitting ducks out of the Chinese infantry as the IX Corps defenders saturated the all-out assaults with massed firepower of every caliber.

On 12 October there was a break in the bitter struggle. The 30th ROK Regiment passed through the dug-in 29th Regiment and counterattacked. In the morning the 28th Regiment moved up through the Both and pressed the assault. Leapfrogging the battalions of the leading regiment and substituting attack regiments from time to time, the ROK 9th Division began to inflict extremely large casualties on the enemy. By 15 October the battle for White Horse was over.

Although the Chinese had used a force estimated at 15,000 infantry and 8,000 supporting troops during the ten-day contest, they had failed to budge the ROK 9th Division. Despite ROK losses of over 3,500 soldiers during the nine ROK and twenty-eight Communist attacks, the 9th Division and its supporting troops had exacted a heavy toll from the Chinese 38th Army. Seven of the 38th Army's nine regiments had been committed to the White Horse and Hill 281 battles and taken close to 10,000 casualties.

Throughout the fight, the timely injection of fresh troops by General Kim on both offense and defense had sparked the ROK effort. The ROK units had withstood the determined drive of the Chinese infantry and taken over 55,000 rounds of enemy artillery during the battle. The performance of the ROK 9th Division under fire provided an excellent testimonial to the type of leadership, skill, and experience that the ROK Army was capable of developing and won high praise from Van Fleet.56

The ROK 9th Division received outstanding support from the air, armor, and artillery units that backed up the division. During the daylight hours, the Fifth Air Force had dispatched 669 sorties and another 76 sorties had been sent out on night bombing missions. In ten days the tactical air support had dropped over 2,800 general-purpose bombs and 358 napalm bombs and launched over 750 5-inch rockets at enemy concentrations and positions. From IX Corps artillery alone, f 85,000 rounds of artillery ammunition had been hurled at the Chinese. Tanks and antiaircraft quad-50's had protected the flanks of the hills and prevented the enemy from dispersing its attacks. At White Horse, prebattle preparation, made possible by effective intelligence, added to welltrained troops, skillfully employed, and backed by coordinated air, armor, and artillery support, demonstrated what might be accomplished on defense. White Horse seemed a prime example of the kind of action that General Clark had argued for earlier in the summer.

Jackson Heights

In addition to the diversionary attack on Hill 281, the Chinese had attempted to disperse the ROK 9th Division forces by threatening the ROK outpost positions on Hill 391 almost seven miles northeast of White Horse Mountain on the eastern divisional front. Sporadic and indecisive fighting continued from 6 to 12 October when the enemy made a serious effort to storm the hill. After the ROK units pulled back, a reinforced company from the U.S. 7th Division attempted in vain on 13 October to regain the lost positions.57

Once the White Horse issue was settled, the ROK 9th Division sent a battalion from the 28th Regiment to clear Hill 391 on 16 October. The battalion won through to the crest and was able to maintain control until 20 October, when enemy counterattacks regained possession of the hill for the next two days. On 23 October, after a bitter handto-hand encounter, elements of the ROK 51st Regiment drove the Chinese off again, repulsed a counterattack, then withdrew. On the following night the 65th Infantry Regiment relieved the ROK 51st on the line.58

Since the unsuccessful battle for Outpost KELLY the 65th Regiment had been undergoing a vigorous program of training under a new commander, Col. Chester B. De Gavre. Two weeks of intensive training, however, could not remedy the basic weakness of the regiment-the lack of experienced noncommissioned officers at the infantry platoon level-but the unit was again assigned to assume responsibility for a portion of the main line of resistance.59

On the night of 24-25 October, G Company, under Capt. George D. Jackson, took over the defense of the high ground immediately south of Hill 391.60 Jackson Heights, as it was soon to be called, had enough bunkers to house the command posts of the three rifle platoons, the company headquarters, and the forward artillery observer, but none of these was adequate for fighting off an attack. Captain Jackson's plans for improving his defenses had little chance for early success, since the Chinese artillery and mortar fire upon the heights was accurate and the enemy had excellent observation of the G Company movements from the surrounding hills. Facing the company were elements of the 3d Battalion, 87th Regiment, 29th Division, CCF 15th Army. The 87th Regiment was commanded by Hwueh Yianghua. On the afternoon of the 25th the artillery supporting the 87th Regiment began to send direct 76-mm. gunfire against the Jackson Heights positions from Camel Back Hill, 2,800 yards to the northwest. Enemy 82-mm. and 120mm. mortars followed and by dusk G Company had received 250 rounds of mortar and artillery fire and suffered 9 casualties.

During the night the enemy sent out patrols that probed G Company's dispositions and continued to send harassing artillery and mortar fire onto Jackson Heights. Captain Jackson used his own 60-mm. mortars and supporting mortar and artillery fire to break up the Chinese probes.

Late in the afternoon of 26 October the enemy sent over 260 rounds of direct 76-mm. gunfire from Camel Back Hill and caused 14 more casualties. From the company listening posts that night came frequent reports of the enemy moving about and digging in. Two Chinese approached within hand, grenade range of one of the listening posts on the southwest flank. The men at the post were given permission to use grenades against the interlopers. As the two men hastily withdrew, mortar fire was called in to speed their departure.

An enemy platoon probed the northern approach to Jackson Heights shortly after midnight, then fell back under interdicting artillery and mortar fire. Another platoon advanced from the north an hour later and closed to hand grenade range. After a 15-minute fire fight, the Chinese pulled back, taking an estimated 17 casualties with them.

The next eight hours were relatively quiet. Then, about 0930 hours on 27 October, the 76-mm. guns on Camel Back Hill opened up again. One enemy round scored a direct hit on the mortar ammunition supply and blew up all but some 150 rounds. By nightfall the Chinese firepower had reduced the mortar platoon to two mortars and seven men and the second platoon had lost both its platoon leader and sergeant. Captain Jackson reported to 2d Battalion that he needed aid for his wounded and wanted smoke laid about the heights to obstruct the enemy's ability to pinpoint the company's movements. He was told to be calm, that smoke and aid were on the way.

So were the Chinese. An hour after Jackson called, they loosed a heavy concentration of artillery and mortar fire on G Company's positions and then sent an estimated company in from the north. Using the remaining mortars, automatic weapons, small arms, and hand grenades, Captain Jackson and his men beat off this attack.

The second enemy assault of the evening came after the Chinese artillery and mortar crews had fired an estimated 1,000 rounds at Jackson Heights within half an hour. One estimated Chinese company struck from the north and a second from the south. Jackson called for final defensive fire on the area until the situation clarified. His ammunition dump had been hit again and the enemy attack had fanned out and become general on all sides.

At this point the company communications sergeant evidently reported that there were only three men left in the platoon in his area and asked battalion for permission to withdraw. Whether the sergeant acted on his own or not was unclear, but Colonel Betances, the battalion commander, assumed that the request was from the company commander and ordered G Company to withdraw. When Captain Jackson learned of the withdrawal order, he attempted to verify it, but the communications lines were out and radio contact proved unsatisfactory.

At any rate, Captain Jackson passed the order to withdraw back to his platoon leaders. The first and second platoons went down the east side of the heights and Captain Jackson went with the third platoon down the western slope. His platoon ran into heavy enemy small arms fire on the way and he was separated from his men during the action, finally rejoining them on the trail back to the main line of resistance.

When Colonel De Gavre learned of G Company's withdrawal, he quickly ordered that A Company, commanded by 1st Lt. John D. Porterfield, be placed under the operational control of Colonel Betances for a counterattack to regain Jackson Heights. A Company was to be used for the attack phase only and F Company, commanded by Capt. Willis D. Cronkhite, Jr., would take part in the attack and then would man the outpost. C Company, under Lieutenant Stevens, would prepare to pass to the operational control of the 2d Battalion, if it were necessary to back up the attack.

As daylight broke on the 28th, Captain Cronkhite led F Company toward Jackson Heights. The Chinese platoon defending the hill resisted with small arms, automatic weapons, and hand grenades, but F Company won control of the crest by 1000 hours. In the meantime, progress by Lieutenant Porterfield's A Company had been slowed down by artillery and mortar fire. Despite the enemy fire, two platoons pushed on and joined F Company on the heights; the remaining platoon was pinned down by mortar fire at the base of the hill.

The operation seemed to be well in hand, until the Chinese artillery put all of A Company's officers on the hill out of action. One platoon leader was killed by a direct hit and then a shell landed in the middle of the company command post killing Lieutenant Porterfield and the forward observer and wounding the one remaining platoon leader. The loss of leadership became immediately apparent, for enlisted men in both A and F Companies began to "bug out." Slipping away from the heights alone or in groups, the men drifted back toward the main line of resistance. By late afternoon only Captain Cronkhite and his company officers remained on the hill; all of his men had left along with those of A Company.

Efforts by the 2d Battalion to round up the stragglers and send them back to Jackson Heights met with no success. The men by this time evidently regarded the hill as a suicide post and refused to return. When night fell, Colonel Betances ordered Captain Cronkhite and his fellow officers to withdraw from the hill.

On the following day the 65th Regiment made one more effort to take Jackson Heights. Colonel De Gavre put Major Davies, the 1st Battalion commander, in charge of the operation. Davies sent C Company, under Lieutenant Stevens, to Jackson Heights in the morning of 29 October. The company moved up and took possession of the hill without encountering any enemy resistance. Again all seemed well. The enemy artillery was quiet and no counterattack developed. Suddenly fear set in and the enlisted men left en masse. Lieutenant Stevens and his fellow officers found themselves alone with a handful of men.61 Once more the stragglers were gathered together and ordered back up the hill and over 50 refused. Major Davies finally recalled Lieutenant Stevens and his little group to the main line of resistance.

This proved to be the last attempt of the 65th Regiment to take Jackson Heights. Maj. Gen. George W. Smythe, the division commander, ordered the 15th Infantry Regiment to take over responsibility for the 65th's sector beginning that same night.62 In November the 65th Regiment returned to an intensive training program. General Smythe requested that a combat-trained regiment be either assigned permanently or for at least four months while the 65th Regiment underwent its retraining. If neither of these alternatives were possible, Smythe went on, he favored the reconstitution of the regiment with 60percent continental personnel and the assignment of the excess Puerto Ricans to other infantry units.63

At any rate, the U.S. 15th Regiment took over the defensive positions of the 65th in late October. Outposts set up on Jackson Heights were subjected to frequent probes by the enemy throughout the first half of November. By the middle of the month only a couple of outposts at the base of Jackson Heights remained in the possession of the 3d Division. Although the Chinese exerted considerable pressure upon the outposts during the remainder of November and overran them several times, elements of the 15th Regiment managed to maintain their precarious postions at the end of the month.64

Operation SHOWDOWN

As the indications that the Communists were seizing the initiative on the ground became more apparent in late September and early October, General Van Fleet grew concerned. In his letter of 5 October to Clark urging the approval of a limited objective attack on the U.S. IX Corps front, he commented: "It is extremely desirable that we take the initiative by small offensive actions, which will put the enemy on the defensive in order to reverse the present situation. Our present course of defensive action in the face of the enemy initiative is resulting in the highest casualties since the heavy fighting of October and November 1951."65

To offset this trend, Van Fleet recommended the adoption of the IX Corps plan, called SHOWDOWN, that was designed to improve the corps defense lines north of Kumhwa. Less than three miles north of this city, Van Fleet pointed out, IX Corps and enemy troops manned positions that were but 20o yards apart. On Hill 598 and Sniper Ridge, which ran northwest to southeast a little over a mile northeast of Hill 598, the opposing forces looked down each other's throats and casualties were correspondingly high. If the enemy could be pushed off these hills, Van Fleet went on, he would have to fall back 1,250 yards to the next defensive position. Counting on maximum firepower, consistent with ammunition allowances, and maximum close air support, the Eighth Army commander was optimistic about the possibilities of SHOWDOWN.66

Although Clark had voiced his opposition to hilltaking expeditions in the past, he evidently decided that SHOWDOWN offered a better than average chance for winning its objectives without excessive casualties. If all went according to plan, two battalions, one from the U.S. 7th Division and the other from the ROK 2d Division, would be sufficient to accomplish the mission. The field commanders estimated that the operation would take five days and incur about 200 casualties. With sixteen battalions of artillery mounting some 280 guns, and over 200 fighter-bomber sorties in support, the infantry was not expected to encounter serious obstacles.67 At any rate, Clark approved SHOWDOWN on 8 October, but cautioned Van Fleet to give the operation only routine press coverage and to stress the tactical considerations arguing for the seizure of the hills.68

Efforts to treat SHOWDOWN as a routine operation were doomed from the start by the Chinese. Although the five days of preparatory air strikes had to be reduced to two because of the demands of White Horse Hill and because the artillery support also had to be curtailed, the Chinese were ready for the attack and soon demonstrated that they intended to hold on to the Hill 598-Sniper Ridge complex.

Hill 598, the objective of the American troops, was V-shaped with its apex at the south. (Map 6) At the left extremity of the V lay Pike's Peak and on the right arm were two smaller hills christened Jane Russell Hill and Sandy Ridge, from north to south. The resemblance of the Hill 598 complex to a triangle soon led to the designation of the area as Triangle Hill. On 14 October 1952 the hill mass was defended by a battalion of the 235th Regiment, 45th Division, CCF 15th Army, one of the Chinese elite armies. As usual, the enemy was well dug in, had adequate ammunition supplies, and defiladed reinforcement routes.

Maj. Gen. Wayne C. Smith, the 7th Division commander, assigned the mission of taking Triangle Hill to the gist Infantry Regiment, commanded by Col. Lloyd R. Moses. Although the original plan had called for the use of one battalion in the assault, Colonel Moses and his staff estimated that enemy resistance would be greater than previously anticipated and that it would be impossible for one battalion commander to control all the forces operating in the entire objective area. Thus, he assigned the task of seizing the right arm of Triangle Hill to his 1st Battalion, under Lt. Col. Myron McClure, and the mission of gaining possession of the left arm to the 3d Battalion, commanded by Maj. Robert H. Newberry. The forces committed to the assault had doubled before the operation began.69

After the air strikes and artillery preparations had placed tons of explosives on Triangle Hill, Major Newberry sent the 3d Battalion in a column of companies to take the apex of the hill complex. L Company, commanded by 1st Lt. Bernard T. Brooks, Jr., moved out first, followed by K Company, under 1st Lt. Charles L. Martin. In reserve, ready to assist either of its sister companies, was I Company, commanded by Capt. Max R. Stover.

As Lieutenant Brooks led his company out of the assault positions, he ran into immediate trouble. From a strongpoint on Hill 598 the Chinese sent hand grenades, shaped charges, bangalore torpedoes, and rocks to disrupt L Company's attack. In less than half an hour, Lieutenant Brooks and all his platoon leaders became casualties and the remainder of the company was pinned down in a small depression below the enemy strongpoint.

After the assault bogged down, Lieutenant Martin moved K Company forward. Securing tank fire to knock out the Chinese strongpoint that had dominated the fight thus far, Martin rallied L Company and got the men again moving ahead.

A few men from the two companies managed to work their way-into the outlying trenches on Hill 598, but the Chinese evidently had no intention of withdrawing from the crest. They hurled numerous hand grenades and liberally expended small arms ammunition, shaped charges, and torpedoes to repel the 3d Battalion.

With the casualty list mounting and the attack again slowing down, Major Newberry committed I Company to the battle. Captain Stover took his men up Sandy Ridge, which had been captured by the 1st Battalion, and then moved southwest along the ridge line toward Hill 598. Since the Chinese were well dug in, I Company had to proceed slowly, rooting the enemy out of the holes and trenches. As night fell, Captain Stover's men began to meet with increasing artillery and mortar fire. Enemy troops were spotted massing for a counterattack and Stover called for defensive fire. Disregarding the artillery and mortar concentrations laid down by the units supporting the 3d Battalion, an estimated two companies from the 135th Regiment passed through the fire and hit I Company with small arms, automatic weapons, and grenades.

The fierce enemy resistance and the growing casualty list led to a consultation between Colonel Moses and Major Newberry early in the evening. They decided to pull back all three rifle companies to the main line of resistance. By 2100 hours, the 3d Battalion had reassembled and taken up blocking positions.