History  On Line

On Line

A settlement of the truce negotiations or a continuation of the hot war might have obscured several of the problems that became important during the winter of 1951-52. But the absence of conclusive developments either at Panmunjom or on the battlefield focused more attention upon the flow of affairs in the rear areas. The lack of decision in the debates and at the front did not obviate the need for decisions behind the scenes. Regardless of the details of the eventual agreement at Panmunjom, the basic problem of the Communist threat in the Far East would remain. By November 1951 it was evident that no military decision would be won or even sought. What, then, would come after the armistice?

Since World War II the United States had provided the chief opposition to the spread of communism all over the world. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization, formed in 1949, offered a nucleus for resisting further Communist aggrandizement in Europe. By the close of 1951 the United States had built up the American forces on the European continent to six divisions and was asking the other NATO member nations to increase their contributions. Progress was slow since rearmament and upkeep of armed forces were expensive items and the threat of war in Europe did not appear to be critical. In February 1952, however, an event of considerable importance for NATO took place when the NATO conference held at Lisbon approved plans for a fifty-division NATO ground force that would include German elements for the first time. The news of the rearmament of West Germany and its future participation in NATO evoked protests from the Soviet Union, but these were rejected by the United States, the United Kingdom, and France. The addition of West Germany forged another link in the European defense line, but whether this link would be a source of strength or a weakening liability was as yet unknown.

In the Far East, on the other hand, the United States stood alone. The colonial commitments of Great Britain and France in Africa and Southeast Asia ruled out hope of major assistance from them in the near future. Unless the United States wanted to continue to shoulder the burden, only one practical alternative remained-to tap the manpower potential at hand in the Far East. To fashion an effective force that would have the training and equipment as well as the will to fight against Communist encroachments would be expensive and time consuming, but not as costly as maintaining large numbers of U.S. troops in the area. Fortunately a start had been made in the Republic of Korea, Nationalist China, the Philippines, and Japan. Military assistance advisory groups had begun the long-term tasks of developing national forces to withstand aggression. The main problem would be to strengthen and accelerate the military aid program so that ultimately the United States could delegate some of the responsibility for the defense of the Far East against Communist expansion.

Improving the ROK Army

As long as the war continued, the Republic of Korea would remain the most critical link in the defense chain. Here lay the direct threat to a nation sponsored and supported by the United States- a threat that could not be ignored or evaded without endangering the entire U.S. position in the Far East. To meet the Communist challenge the bulk of the U.S. military forces in the Far East had been committed to the war in 1950 and reinforcements from the United States had quickly followed with a resultant drain upon the strategic reserve. The only hope for halting this flow of manpower seemed to rest in the substitution of Korean troops for U.S. soldiers. But before Korean forces could take over and successfully defend their own liberties, much remained to be done.

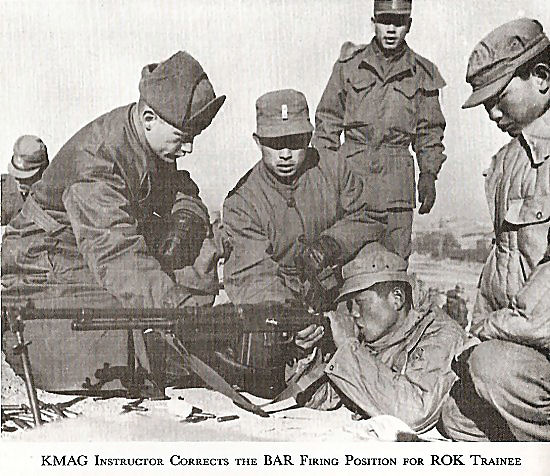

The Army, as has been mentioned previously, had begun to work on the task.1 Operating through the Korean Military Advisory Group, active steps were under way to improve the quality and efficiency of the ROK Army. Both the Secretary of the Army, Mr. Pace, and the Chief of Staff were personally interested in the progress of the KMAG plan of action and this helped to remove some of the obstacles that had hampered the program.2

Basically the chief impediment had been time. Until the pressure on the battlefield had lessened, it was impossible to withdraw units for training or refresher courses. Replacements frequently were rushed up to the front lines with insufficient instruction in tactics and weapons. It was a wasteful process, but, under the circumstances, necessary.

When the fighting slacked off in July, General Ridgway and his advisors began to devote more attention to the adequate preparation of men and units for combat. The raw material supplied by the ROK was good, although often undernourished. If properly led, the average Korean youth showed courage, stamina, and a great deal of native patience- all excellent qualities, especially in a defensive war. Despite the variable performance of the South Korean forces during the first year of the war, military observers were convinced that most of their worst moments could be traced directly to poor leadership and lack of training. It was against these weaknesses that KMAG launched its main assaults.

In the program outlined by Ridgway in July 1951, the chief objective was to correct the leadership problem by re-establishing and reinvigorating the South Korean military school system. Now that time was available, he hoped eventually to create a professionally competent officer and noncommissioned officer corps.3 This did not promise to be an easy project. The ROK Army did not pay its officers or enlisted men more than a pittance, considering the inflationary trend of the South Korean economy. It was hardly surprising that many of the officers should try to make ends meet by resorting to questionable expedients, but it was not conducive to the creation of a good army when these same officers put personal benefits ahead of military necessity. Despite the continual pressure that KMAG applied upon the ROK Government to take severe disciplinary measures against corrupt officers, the problem was likely to remain until the officers received sufficient compensation to support themselves and their families.4

Another element in the complex undertaking of building a capable officer corps was the instilling of confidence at all levels-confidence in the officers among the soldiers and confidence of the officers in themselves. The average South Korean officer was young, and in many cases regiments were commanded by men under thirty. Yet despite the leavening factor of youth, caution was characteristic. In the absence of higher authority or direct command, juniors were usually reluctant to act lest they offend their superiors. The dearth of initiative would not be simple to compensate for. It was a basic deficiency that arose from the emphasis that the Koreans placed upon rank and seniorityyou bowed to those above you and bullied those below you. As long as this condition lasted, few ROK officers would be willing to risk offending their superiors by taking independent action. To counter this tendency, KMAG instructors would have to exert skill and patience over a considerable length of time.5

While KMAG attempted to implant confidence, initiative, and professional skill in the upper echelons, a Field Training Command was put into operation behind the lines to bolster the morale of the soldiers. As each ROK division was rotated through a nineweek course of basic training, refresher instruction in weapons and tactics helped to weld the fighting units into better combat teams. The success of the course of training led to the establishment of three additional camps - one in each corps area- in September 1951.6

By the beginning of November 1951 considerable progress was made in the organization of the school and training system. The Replacement Training and School Command under General Champeny had acquired additional personnel and was ready to handle large groups.7 To centralize training installations the RTSC recommended that the Infantry School, Artillery School, and Signal School all be relocated at Kwangju in southwestern Korea, about 120 miles west of Pusan. The consolidated school opened in early January and was given a new name the following month- The Korean Army Training Center. Up to 15,000 troops could be instructed at one time at this installation.8

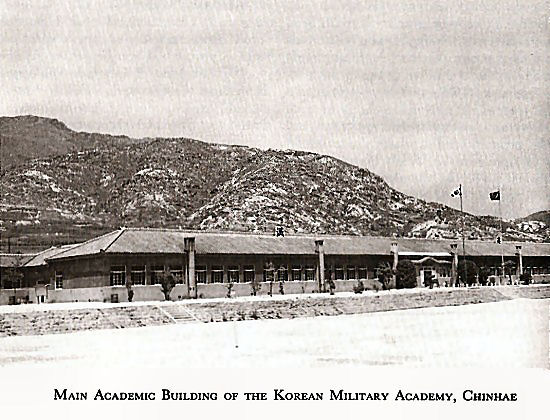

At the officer candidate school level the course was extended from eighteen to twenty-four weeks to provide extra training for the new company grade officers. And on 1 January 1951 the Korean Military Academy reopened its doors at Chinhae near Pusan with a full fouryear curriculum patterned after West Point. For field grade officers a Command and General Staff School was established at Taegu and officially launched on 11 December 1951.9

In the meantime 150 ROK officers attended the Infantry School at Fort Benning, Georgia, and another 100 took the course at the Artillery School at Fort Sill, Oklahoma. From this group trained in U.S. schools the Army hoped to recruit the future instructors for the ROK Army. As a whole, the officers chosen to go to the U.S. service schools were the pick of the crop and did well at their studies. The chief problem, as usual, was that of language and interpreters had to be sent along with the students, but many of the latter took advantage of their tour in the United States and learned some English as well. Since few Americans learned to speak Korean, this was to be of great value when these officers later returned to Korea. The problem of communication between Korean and American soldiers was a continuing and perplexing one, especially when technical exchanges took place. The first group of ROK officers graduated from the U.S. schools in March 1952 and a second contingent of 250 officers left Korea the same month to begin the next cycle.10

The growing effort in behalf of the ROK Army increased the demands upon KMAG and led to a request from Ridgway that the group be augmented. On 1 November the Department of the Army approved an expansion of over 800 spaces for KMAG, bringing its total strength to over 1,800 officers and men.11

As the ROK Army began to improve in quality, Acting Secretary of Defense William C. Foster raised the question of its ultimate quantity. On to November he requested the JCS views on the mission and size of the postwar ROK defense force.12 Since both MacArthur and Ridgway had consistently favored a ten-division, 250,000-man army the JCS recommended that this figure be maintained despite the fact that the President and his advisors had decided in the meantime to increase ROK military strength.13 The Joint Chiefs informed the Secretary of Defense in late January 1952 that the ROK economy did not have the capability to sustain a significant expansion of military forces in the near future. In their opinion, the present ROK units, when properly trained, equipped, and led, should constitute a sufficient deterrent to further aggression or, if the occasion demanded, could delay Communist advance until reinforcements could be brought in.14 The ROK Government was in the throes of a serious financial crisis as a result of steady inflation and hardly in a position to assume additional heavy expenses, it is true, but this was but one facet to the problem. It should not be forgotten that the United States had made commitments to supply many of the military requirements of its NATO allies and was about to sponsor the renascence of the Japanese defense forces as well. With U.S. production not on a full war scale and with heavy demands at home and abroad to be met, it appeared that ROK Army expansion would have to await a more opportune moment.

The ROK Government and its most effective spokesman, President Rhee, did not, of course, agree that an army of ten divisions would be enough to defend South Korea in the postwar period, but the matter lay quiescent until late March 1952. During an inspection trip to Korea, Secretary of the Navy Dan Kimball discovered that General Van Fleet favored the formation of ten additional ROK divisions. When he reported this item to the Army Policy Council upon his return there was considerable consternation. This was the first intimation that the Army had received of strong support for ROK Army expansion and it was a little humiliating to have to get the information from the Navy. In any event General Hull immediately asked Ridgway for an explanation.15

Ridgway was just as surprised as his superiors had been and forthwith queried Van Fleet. In this roundabout manner he was finally informed by the Eighth Army commander that the latter did believe in the expansion of the ROK Army to twenty divisions. Van Fleet maintained that the ROK had the manpower and the desire to fight and the United States could support ROK troops in Korea much more economically than American forces. As a conclusion to a somewhat amazing performance, Van Fleet referred his commander to an interview he had just had published in the U.S. News and World Report, if Ridgway desired more information on his views.16

Whatever Ridgway's personal reaction to this turn of events may have been, he exercised remarkable restraint. He told Hull that he had not seen Van Fleet's magazine interview, but nevertheless he flatly disagreed with his subordinate on doubling the ROK Army. Not only was the ROK economy unable to additional forces, but he thought that the development of the Japanese defense forces should be given preference at this time. The training program for the ROK ten-division army was just beginning to bear fruit, he went on, but it would take another ten months before it was completed. If the United States started to organize ten additional divisions it would require eigtheen months to prepare them for action and the United States would also have to furnish all subsistence, clothing, and pay. Although he had the utmost respect for General Van Fleet, Ridgway informed Hull that "His outlook, however, in this particular case is in my opinion quite naturally focused almost exclusively on the Korean situation, as that situation affects the U.S. I cannot believe due consideration has been accorded to the inseparable relation of the Japanese, Chinese Nationalists, and Southeast Asia military programs to which the United States Government is committed, or which it has under study."17

General Ridgway's disapproval was enough to prevent an increase in the ROK ground forces and when he left the Far East Command in May for a new assignment as Supreme Allied Commander, Europe, no change had been made in the size of the army. In the matter of ROK air and marine forces, however, the Far East commander ran into more difficulty. The ROK Air Force was small and equipped with propeller-driven planes. In Ridgway's view, a 4,000-man air force with seventeen obsolescent fighters and twenty-nine miscellaneous craft could offer no real opposition to a future Communist air sweep and would probably be wiped out quickly. Maintenance of a tiny, impotent force was wasteful, Ridgway continued, since in the event of renewed aggression the United States would still have to provide air support for the ROK. "A second best Air Force is worse than none," he told the JCS.18 But the U.N. commander found that it was next to impossible to abolish a service once it gained a firm foothold. The JCS showed no disposition to tamper with the ROK Air Force and no action was taken on Ridgway's recommendation.

The same reception met his proposal to dispense with a separate marine force after the war. To his way of thinking, a marine division would require separate overhead and support elements that would duplicate those of the Army and this needless expense would have to be borne by the U.S. taxpayer.19 The U.S. Navy, however, had already established both a Naval Advisory Group and a Marine Advisory Group to the ROK in February, and Ridgway's plea went unheeded.20

Despite the mixed success of Ridgway's efforts to restrict the size of the ROK armed forces, he and his staff did manage to effect several internal improvements aimed at bolstering the efficiency of the ROK troops. In November Ridgway authorized Van Fleet to increase the strength of the Korean Service Corps to 60,000 men. This would permit all the laborers and carriers in the combat areas to be organized and brought under tight control and discipline. It would also assure the fighting corps of more reliable service support. Eventually Ridgway planned to raise the ceiling of the Korean Service Corps to 75000.21

The U.N. commander also made efforts to correct one of the basic weaknesses of the ROK Armythe lack of adequate integral artillery support. In the past ROK divisions had been forced to rely upon U.S. artillery support for most of their offensive and defensive missions. Only one 105-mm. howitzer battalion was assigned to each ROK division as opposed to three 105-mm. and one 155-mm. battalions in each U.S. division. In addition, the latter had tank support and more heavy mortar companies available to perform its tasks. Previously the Eighth Army and Far East Command staffs had argued that the rough terrain, lack of roads, and resupply problems added to the dearth of trained artillerymen and unavailability of equipment had precluded expanding the ROK artillery. But as the war lengthened and settled into its static phase, many of these objections were overcome. In September four ROK 155-mm. howitzer battalions were authorized for activation before the end of the year. These battalions were trained for eight weeks by U.S. corps personnel. Three headquarters batteries and six 105-mm. howitzer battalions were added in November and began their training in January 1952.

Finally in March Ridgway approved a full complement of three 105-mm. and one 155-mm. howitzer battalions for each of the ten ROK divisions. In May the Department of the Army sent interim authorization for the Far East Command to proceed with this program.22

The process of improving the ROK Army was well on its way by April 1952. Schools and training programs to raise the leadership level and confidence of the troops had been started and began to produce demonstrable results. Increased service and combat support to bolster the ROK forces in combat was being organized and equipped. Given time, the ROK Army could become one of the better armies in the Far East.

Relations With the ROK

Military affairs were but one aspect of the problem of conducting a war on the soil of an ally. As the United States had discovered during the World War II campaigns in China, politics played an important role that seemed to increase in inverse ratio to the pressures generated at the front. If the fighting were heavy and external crises dominated the scene, internal politics might be played down or overshadowed. But a static war permitted domestic dissensions to come to the surface and frequently required delicate and diplomatic handling. The situation in South Korea followed this pattern during the armistice period and was to occasion many a tense moment for the U.N. Command in its efforts to fight a war and conclude a peace at the same time.

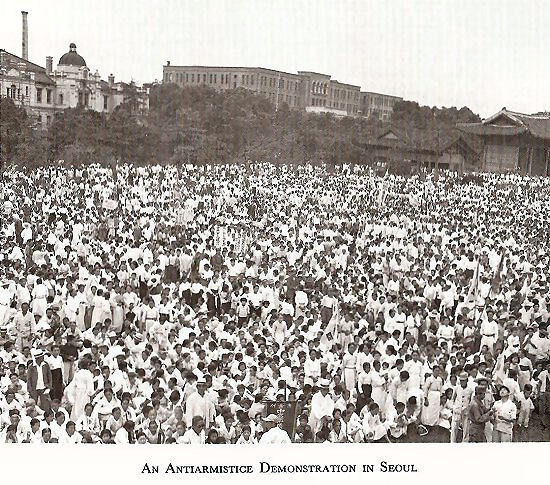

When the armistice negotiations were initiated, President Rhee and his government had firmly opposed a compromise settlement with the Communists. They had no desire to return to the status quo that had been so unsatisfactory in the prewar period and regarded the time as ripe for the unification of Korea- under ROK hegemony. As long as the talks appeared to be making little progress, there was scant reason for vehement action on their part. During the breakdown of negotiations in August, a ROK spokesman had frankly welcomed the turn of events and claimed that the Communists had simply used the discussions as a cover for their military build-up.23

On 20 September, Rhee set forth his terms for dealing with the enemy- terms that the Communists could not possibly accept without admitting defeat. First the Chinese should withdraw from Korea and the North Koreans should be disarmed. Then the latter would be given full representation in the Korean National Assembly and presumably this would settle the whole problem. The ROK President felt that the Communists should be given a time limit for acceptance; otherwise the negotiations should be concluded. In his opinion, the enemy was using the talks to humiliate and discredit the United Nations in the eyes of the Communist world.24

After the negotiations resumed in October, the ROK Government expressed its dissatisfaction in many ways. A favorite method was through "spontaneous" demonstrations similar to the one staged by students in Pusan in early December. Close to 500 students gathered and paraded through the city carrying signs and placards bearing such anticease-fire slogans as "No Armistice Without Unification."25 These apparent popular outbursts of indignation against the truce meetings could be mounted quickly whenever there seemed to be a possibility of agreement at Panmunjom.

The continual ROK agitation and hints from Rhee that the government might not observe the terms of an armistice disturbed General Ridgway. It may be remembered that the UNC control over the ROK armed forces rested upon Rhee's July 1950 letter to MacArthur assigning command to the latter and anyone he delegated for the duration of the hostilities only. In the months that had followed the ROK Government had faithfully observed this pledge and it had not been considered necessary to seek a firm written understanding on the matter. But by early 1952 Ridgway felt that a formal agreement covering the armistice period should be secured to forestall independent action by the Republic of Korea in opposition to the truce stipulations. Unless the ROK military forces remained under UNC control after the truce was concluded, there was a distinct possibility that the truce would be short-lived. Under the circumstances, Ridgway urged a high-level governmental approach to secure a written commitment on armed forces and, at the same time, to stop the ROK antiarmistice campaign.26

While the U.S. political and military leaders recognized the danger, they doubted that the proper moment had arrived to negotiate with the ROK Government on the future control of its military power. To reach an understanding while ROK emotions were running high might result in the imposition of conditions unacceptable to the U.N. Command and jeopardize the achievement of an armistice. Therefore they preferred to work out the terms of the truce first and use the presence of UNC forces in Korea and the supply and training of South Korean troops as persuasive points to gain ROK compliance later.27

They were more sympathetic to the suggestion that President Truman might make an appeal to Rhee to halt the massive ROK assault on the armistice. On 4 March the President informed Rhee of the concern of the United States over the ROK attitude toward the truce. He pointed out that the U.N. unity of purpose in Korea must be maintained at all costs since divergencies might threaten the support of the U.N. and then issued a note of warning:

The degree of assistance which your Government and the people of Korea will continue to receive in repelling the aggression, in seeking a just political settlement, and in repairing the ravages of that aggression will inevitably be influenced by the sense of responsibility demonstrated by your Government, its ability to maintain the unity of the Korean people, and its devotion to democratic ideals.28

The stress that the President laid on the relationship between ROK actions and U.N. assistance could not but have its effect upon President Rhee and his staff. From the close of World War II down to the outbreak of the Korean War the United States had made substantial contributions to the South Korean economy. When the war began in 1950, again it was the United States which had taken the lead in sending military and economic aid. Food, clothing, and supplies for the thousands who were displaced and for the sick and wounded were provided not only for humanitarian motives, but also with the realization that unrest and disease within the UNC area would complicate the military operations then under way. The United States also had long-range plans for relief and rehabilitation that it intended to carry out under U.N. auspices as soon as the war was over. It had taken the lead in proposing and supporting the formation of the United Nations Korean Reconstruction Agency (UNKRA) that was established on 1 December 1950 and had provided the new agency the bulk of its funds.29

Although the prolongation of the war delayed the effective functioning of UNKRA, the U.N. Command set up the U.N. Civil Assistance Command in Korea under the Eighth Army in early 1951 to prevent disease and unrest. Designed to safeguard the security of the rear areas, UNCACK engaged primarily in relief work, providing consumer goods to meet the immediate needs of the civilian population. The comparative inactivity at the front during the truce negotiations permitted reconstruction and rehabilitation to begin while the fighting was still going on. By the end of 1951, Ridgway and the UNKRA officials had fashioned a working agreement that allowed UNKRA to start on a limited reconstruction program subject to the approval of the UNC.30

Thus the actual control over relief and economic assistance to South Korea remained under UNC control as long as military operations continued and for a six-month period after an armistice was concluded. This, of course, strengthened the hand of Ridgway in his dealings with the ROK Government. But the exigencies of war and the pouring into Korea of U.S. money, goods, and services led to a repetition of the U.S. experience in China in World War II. The undeveloped economy of the ROK, disrupted by war and essentially agricultural, could not absorb the added purchasing power that large military expenditures brought into being. While the ROK Government resorted to the printing press to meet the demands for more currency in connection with military operations, it could not siphon off the growing supply of money in circulation by increasing industrial production or by larger imports of consumer goods. U.S. aid helped somewhat, but the $150,000,000 that had been expended by 15 September 1951, plus fifty million dollars' worth of services and ten million dollars in raw materials could not stem the tide of inflation.31

By January 1952 the ROK financial situation had become critical. Although the deficit spending indulged in by the ROK Government and the bank credit expansion practices that were permitted contributed to the inflationary trend, the ROK officials placed the principal blame upon the advances in Korean won made to the UNC for military requirements. They charged that the U.N. Command had failed to settle in dollars for the won issued and intimated that they would not be able to provide more currency to the UNC after January.32

By an agreement signed on 28 July 1950 the ROK Government had pledged itself to supply the currency needed by the UNC and to defer the settlement of claims arising from this procedure until a time satisfactory to both parties. The hint that the ROK might not meet its obligation worried Ridgway. He had no objection to making monthly settlements in dollars for the won advances as long as the UNC retained some control over ROK foreign exchange. To help counteract inflation he proposed that the UNC secure ROK currency by sale of imported commodities to the Korean people and by purchasing won at the best rate through any legal source.33 In addition, Ridgway believed that by making book settlement for UNC services, with no actual use of money, the amount of currency in circulation could be held down.34

But the ROK Government balked at permitting the U.N. Command to maintain control of its foreign exchange and negotiations between the two came to a halt in February. In the meantime the UNC had drawn eight million dollars' worth of won in January as opposed to only six million dollars' worth in December and Ridgway asked Van Fleet to give his personal attention to the problem of holding down expenditures involving the use of won.35 The gravity of the spiralling inflation can be easily seen in the increase of currency in circulation between 1 July 1951 and 1 March 1952 - from 122 billion to 812 billion won.36 The impasse in the financial negotiations and the ever-rising inflation coupled with the ROK attitude toward the armistice and domestic complications in the ROK Government prompted Ridgway and Ambassador Muccio to suggest in early March that a high-level mission be sent from Washington to reach an understanding on the entire field of ROK-UNC relations.37 Impressed by the urgency of Ridgway's request, the Department of the Army moved quickly to prepare for the dispatch of a mission. Defense and State Department approval was soon obtained. On 28 March the President named Clarence E. Meyer, head of the Mutual Security Administration mission to Austria, as chief of the delegation. The Department of State agreed to act as monitor since the mission was given a broad directive to negotiate "financial, economic and other appropriate agreements between the United States or the Unified Command and the Republic of Korea."38

The end result was an agreement signed on 24 May between the Unified Command and the ROK. Considering the political turmoil that was rampant in South Korea and the strong feelings expressed about national sovereignty, the Meyer understanding represented a fair compromise. The most important provision established a Combined Economic Board with one Unified Command and one ROK member to promote effective economic co-ordination. The board would make recommendations that would be binding on the use of all foreign exchange and integrate it with the UNC assistance programs. As for the UNC won advances, the Unified Command agreed to settle up for all advances made between 1 January 1952 and 31 May 1952 at the 6,000-won-to-a-dollar rate. Claims for 1950-51 would be deferred until a later date and claims for future months would be paid for at a more realistic rate than 6,000 to 1. Ten percent of the amount advanced each month would be written off by the ROK Government as its contribution to the war effort. In addition, the ROK Government agreed to take internal measures to control inflation and the Unified Command would attempt to draw won from the market by bringing in as many salable goods as possible.39

If both sides made sincere efforts to carry out the terms of this agreement, the economic situation in Korea could improve considerably in the near future. Whether this might also have a favorable influence upon the political and armistice problems was another matter. By May 1952 the armistice negotiations had again reached a stalemate and ROK agitation against the truce had subsided, but President Rhee's internal conflict with his fellow politicians threatened to build up into another crisis. In any case the U.N. Command might only have adjusted the economic differences in time to be dragged into the political arena. But, at least, one thorn in ROK-UNC relations had been amicably removed.

The Japanese Take a Hand

All of General Ridgway's problems behind the lines did not involve the Republic of Korea directly, but many had an influence upon events taking place on the peninsula. Across the Sea of ,Japan new and complicating elements were introduced in late 1951 and early 1952. From the outset of the war the United States had used the islands of Japan as a huge supply and staging base for the UNC forces fighting in Korea. In his role as Supreme Commander, Allied Powers, Ridgway could employ the facilities available in Japan as he saw fit to support the UNC effort. The signing of the peace treaty in September 1951, however, foreshadowed a period of change as the military government closed out its regime and the Japanese civil authorities once more assumed control of their nation's affairs. In the interim, arrangements had to be made defining the relationship between the U.S. military and civil representatives and the Japanese Government and provision had to be made for the defense of Japan.

Under the Security Treaty signed on 8 September between the United States and Japan, the former was granted the right to maintain armed forces on the islands until the Japanese could build up sufficient strength to defend themselves. The conditions governing the disposition of U.S. troops and the use of Japanese facilities would be worked out by an administrative agreement between the two countries.40

Since the end of the war in Korea remained uncertain and the utilization of Japanese facilities and ports appeared necessary as long as the conflict continued, the Security Treaty afforded the legal basis for the continued presence of U.S. forces in Japan. Even under optimum conditions, it would take considerable time for the Japanese to organize, train, and equip adequate units to defend Japan on their own. And the renunciation of war by the Japanese constitution would make the development of armed forces a delicate matter.

Fortunately, insofar as Japanese defense forces were concerned, a start had been made in mid1950 shortly after the Korean War began. When General MacArthur realized that he would have to deploy the majority of his U.S. units to Korea, he authorized the Japanese officials to set up a National Police Reserve force of 75,000 men. Although the organization ostensibly was formed to preserve internal order, the recruits went through a thirteen-week basic training course during which they became familiar with small weapons and then moved into an eighteen-week course which stressed small unit training and used machine guns and rocket launchers. In June 1951 the Police Reserve engaged in battalion maneuvers. When the armistice negotiations got under way in July, the force was organized into four infantry divisions of 15,200 men each, but it lacked heavy equipment and had not had sufficient training to qualify for other than internal security functions.41

Despite these deficiencies, in May 1951 President Truman approved planning and budgeting for sufficient material to equip ten National Police Reserve Japan (NPRJ) divisions by 1 July 1952. After studying the political and economic factors involved, Ridgway recommended in September that a phased expansion to a balanced ten-division force be adopted. The difficult part, in his opinion, would be the preparation of Japanese public opinion for training of the NPRJ with heavy equipment and armament. This would have to be done by the Japanese Government and Ridgway would see Prime Minister Shigeru Yoshida on this point soon.42

While arrangements for an increased NPRJ went forward in Tokyo, the Department of the Army came up with some disconcerting facts. General Collins informed Ridgway in mid-December that a lack of funds might force the drastic reduction of the NPRJ program. There was no money available from the Mutual Defense Assistance Program and funds for the NPRJ had been cut from the Army fiscal year 1953 budget. Under the circumstances Collins advised Ridgway to revise his plans and endeavor to get along on the funds already allocated.43

Ridgway was shocked. "It is to me incredible that from a national defense budget of $57 billion, we cannot find the relatively meager funds required to support the rapid establishment of a small Japanese army .... For each dollar expended, it is my considered opinion that the U.S. can purchase more security through the creation of Japanese forces than can be purchased by similar expenditures in any other nation in the world, including the United States." The alternative, Ridgway went on, would be to maintain U.S. troops at far greater cost in the Far East. He did not see how he could discuss the NPRJ matter any further with the Japanese until a firm U.S. policy was forthcoming. Vacillation on the part of the United States would create a similar response in the Japanese. If the United States desired to expand the NPRJ more slowly, this might fit in very well with Japanese desires, but Ridgway regarded the proposed cutback "as nothing less than catastrophic to the vital interests of our country."44

The fervent plea of the Far East commander produced a quick reaction in Washington, and by 23 December, Collins was able to allay Ridgway's apprehensions. Secretary Lovett had approved the inclusion of three hundred million dollars in the Army budget for the Japanese defense program.45

Armed with this reassurance, the SCAP staff reviewed NPRJ planning and recommended on 1 January 1952 that priority during the first stage of the expansion be accorded to nondivisional combat units, such as antiaircraft, tank, and artillery, rather than to the formation of new divisions.46 But further implication from Washington that the UNC program could not be carried out in its present form led to another round of messages. The upshot of the affair was that a SCAP delegation, headed by Maj. Gen. William F. Marquat, was sent to the United States in late January to thresh out the matter. After five weeks of consultation, the Army and SCAP representatives fashioned a modus operandi acceptable to both groups. Ridgway would complete the equipping of the four divisions already established and see to it that they became and remained combat-ready in the future. During the next fiscal year the NPRJ would be increased to six divisions with supporting units and the expansion to ten divisions would be phased over fiscal 1954 and 1955, as funds and equipment became available.47

Actually the decision to stretch out the expansion program was not influenced by the lack of money and equipment alone. As it turned out, the Japanese Government had no desire to move quickly in rearming the country. Prime Minister Yoshida would not approve an increase of the NPRJ beyond 110,000 for the 1953 fiscal year. Although SCAP pressed for an augmentation to between 150-180,000, Yoshida declined to make a commitment until after general elections were held in early 1953.48 Since Japanese reluctance to rearm swiftly dovetailed with U.S. financial and production deficiencies in connection with the program, the slowdown in developing adequate Japanese defense forces probably represented a workable compromise.

In the meantime ,Japanese public opinion could be conditioned for the return of Japan to a position of responsibility in the Far East. The United States intended to help Japan by assisting the nation to secure access to raw materials and markets and by encouraging Japanese industry to provide the means by which the country could once again defend itself. Some offshore procurement of ammunition and equipment might be arranged to give the Japanese munitions industry a start, but the Department of the Army felt that the main task had to be accomplished by the Japanese themselves.49

The re-emergence of Japan as a sovereign nation spawned a host of other problems as well. To General Ridgway in his role as Supreme Commander, Allied Powers, one of the most important was the future status of the U.S. and U.N. military forces in Japan. After the peace treaty was ratified, the occupation would end and SCAP would be abolished. Before the latter came to pass, Ridgway wanted to settle the future relationship between the UNC/FEC and the Japanese Government.

On 18 September he outlined his approach to the subject to the JCS. Ridgway pointed out that while theoretically Japan would enjoy full political control, its national security would depend for some time upon both Japanese and U.S. forces. Since this was a military reality, the Far East commander felt that he should have adequate authority to counteract any threat to the security of the U.S. forces under his command and to deal directly with the Japanese Government on all military matters. His orders should come, as in the past, from the JCS or their superiors. He would, of course, coordinate with the chief of the U.S. diplomatic mission to Japan whenever it was necessary.50

The prospective end of military rule in Japan and the return of civilian control, however, had a concomitant-the restoration of normal diplomatic relations and of the pre-eminence of the U.S. Ambassador in intergovernmental intercourse. On 22 December the Army informed Ridgway that the JCS had submitted most of his recommendations to the Secretary of Defense, but that the chief of the diplomatic mission would take precedence over him and be the channel for all governmental matters except those specifically of a military nature.51

During February and March, State and Defense Department representatives worked out further compromises in detail, but it was not until April that they arrived at an agreement that was satisfactory to both sides and approved by the President. It provided that the Ambassador would be responsible for all government relations between the United States and Japan, but that Ridgway would not be subordinate to him in military matters. The Far East commander could negotiate directly with the Japanese Government on security, defense, and military assistance affairs and was authorized to appoint the U.S. member of the newly formed joint Committee.52

Ridgway had insisted upon receiving his orders directly from the JCS and their superiors and this channel of command remained as before. His authority to select the U.S. representative of the joint Committee also came from the JCS as he had desired. The Joint Committee stemmed from the Administrative Agreement signed on 28 February 1952 between the United States and Japan in Tokyo. In the process of establishing the terms under which U.S. forces would remain in Japan and contribute to Japanese defense, a joint Committee with one U.S. and one Japanese member was set up for consultation on the implementation of the agreement. Since such complex matters as the use of ports and facilities, custom regulations, taxes, postal privileges, and legal jurisdiction were covered, the joint Committee was held necessary to straighten out differences of opinion.53

On 28 April the occupation of Japan ended and U.S. military forces assumed a new and diminished position as guests and allies rather than conquerors. But since there would be a long period during which Japanese security would be dependent upon U.S. forces, the Far East commander and his staff retained considerable prestige. The need for protection until Japanese defense forces were ready to take over the major responsibility argued that Ridgway and his successors would wield a goodly measure of influence in Japanese affairs despite the loss of the bulk of their powers. On the other hand, civilian ascendancy had been reestablished and the importance of the U.S. Ambassador was certain to increase as military dependence upon the United States lessened.

The Far East commander meanwhile had the problem of finding out where the Japanese forces would fit into the overall defense picture. Would they fight as separate units or be integrated with U.S. troops if war broke out? Would they come under U.S. supreme command or remain under their own leadership? As yet, no intergovernmental arrangement on the control of Japanese security forces had been reached and the Administrative Agreement merely provided for consultation between the two governments if hostilities threatened. These questions would have to be settled definitively and quickly, General Ridgway believed, and the development of the security forces of Japan closely correlated with those of the Republic of Korea lest they get out of proper balance.54 Since the United States was sponsoring both nations and bad feeling existed between them, the formation of formidable military forces on one side might eventually lead to an unstable situation unless it were matched by a similar development on the other. It seemed apparent by the end of April that although the Japanese were now officially in the game on their own, the United States would be supplying the stakes with which they would play. It would be part of the U.S. task to make sure that the Japanese played along with and not against the other members of the team.

Ammunition Shortages

The complexities of dealing with the ROK and Japanese Governments seem quite simple when compared to the perplexing and tortuous labyrinth of ammunition shortages. In the spring of 1953 a Senate subcommittee conducted a lengthy investigation of the matter and heard from Van Fleet and Lt. Gen. Edward M. Almond as well as Washington defense officials. The testimony given revealed the confusion that existed at the time on the causes and effects of the shortages.55 Much of the confusion stemmed from the lack of background information on the subject.56

At the end of World War II, the United States had a tremendous inventory of ammunition on hand, but unfortunately it was not a balanced stock. There were enormous quantities of some types of ammunition and only small amounts of others. The hasty demobilization that followed stripped the Ordnance Department of the military and civilian personnel that might have properly assessed and cared for the huge inventories of ammunition in its custody. During the years preceding the Korean War, powder packed in cotton bags and fuzes made of substitute metals deteriorated. The Army drew freely upon the big stockpile for training purposes yet made no real effort to replace consumption or to balance the items in stock. Lack of personnel to take a complete inventory and the drive for economy among the Armed Forces contributed to this oversight. Ammunition was expensive and the amounts on hand seemed adequate for years to come under peacetime conditions.

The lack of postwar orders sent the ammunition industry into eclipse. Manufacturers converted to civilian goods and purchased available surplus machine tools to service the booming demands for consumer items that the war had held in leash. When the United States entered the Korean struggle so suddenly in 1950, ammunition facilities and plants were at a low ebb and the prosperity then prevalent made businessmen reluctant to reconvert their factories to wartime products. Another element that restrained a shift to the immediate production of ammunition was the prevalent belief that the Korean War would be short and did not warrant a sizable dislocation of the U.S. industrial effort. Even after this fallacy was shattered by the entry of the Chinese into the war in late 1950, the policy of butter and guns continued and no large-scale mobilization of industry took place.

The sense of complacency that pervaded the nation during the early phase of the Korean War cost dearly, for valuable time was lost in getting the languishing munitions industry back on its feet. Under optimum conditions it took from eighteen to twenty-four months after funds were voted to produce finished ammunition in quantity. Since Congress did not approve the first large appropriation for ammunition until early January 1951, this meant that even under optimum conditions the end products of this money could not arrive on the scene until late 1952 or early 1953.

In the meantime the U.S. and ROK forces in Korea had to live off the stockpile. Fortunately, in addition to the supply of finished rounds of ammunition, there were also large quantities of component parts available that could be used. Since the first months of the war were characterized by a high degree of mobility that required less artillery expenditure, it appeared that the shells on hand and those that could be readily finished were sufficient to carry the United States and its allies through the war.57

As the war ground to a slower pace in mid-1951, artillery assumed a new importance. Static warfare required more artillery missions to harass and interdict the enemy. This meant that the day of supply- the average number of rounds that a gun was expected to fire daily over a considerable period of time-had to be raised.58 Since the day of supply in turn determined the number of shells that were held in reserve in the Far East Command, an expansion in reserve stocks followed.59 The increased demands upon the stockpiles and the knowledge that there was no possibility of replenishing the heavy consumption of artillery rounds until at least late 1952 formed the backdrop to the events of the fall of 1951.

Concern over the theater artillery situation began to arise during the battle for Bloody Ridge in August-September 1951. 2d Division artillerymen fired over 153,000 rounds during the fight and the 1 5th Field Artillery Battalion set a new record for light battalions by firing 14,425 rounds in twenty-four hours. By the end of the action artillery supplies in the theater reserve were greatly reduced but no rationing was introduced except for illuminating shells which were in very short supply.60

Despite denials from the divisions that ammunition was wasted or misused, thousands of rounds of 105-mm. howitzer ammunition were hurled fruitlessly against enemy bunkers on Bloody Ridge. The high trajectory of their fire lessened the chances of direct hits upon the Communist strongpoints and reduced their penetrating power. The job of knocking out the pillboxes and bunkers had to be done by the heavier and more accurate 8-inch howitzers with concrete-piercing shells set for delayed firing and by flat trajectory gun fire. It is interesting to note that after the battle Van Fleet issued a warning against waste of 8-inch and 105-mm. howitzer ammunition since these were then in short supply and at the same time the Eighth Army commander advocated the use of 155-mm. ammunition instead.61

During the assault on Heartbreak Ridge, however, Van Fleet imposed no restrictions upon the 2d Division artillery. But because of the heavy expenditures, local deficits appeared. For example, 4.2-inch mortars had to be used when 81-mm. ammunition ran low and air and rail shipments to the front had to be made to keep the 4.2-inch ammunition on hand.62 It was not surprising that the sustained barrages quickly consumed the supplies on hand in the firing units since original plans for the taking of Heartbreak Ridge envisioned the task as a relatively short and simple one.

The I Corps COMMANDO operation in October demonstrated another phase in the ammunition saga. When the Communists massed their artillery against this advance, UNC guns depleted the stores at ammunition supply points and I Corps had to place restrictions on its artillery units. As it pointed out later, the I Corps did this not only to replenish the supply points, but also to compel units to use up the ammunition they were stockpiling in excess of what they were normally allowed to have on hand.63 Stockpiling was a long-established practice to guard against sudden emergencies and to provide a cushion in case supplies were temporarily cut off.

Although the experiences during the August-October period had to do with local and temporary shortages that were due to a high volume of daily fire, General Ridgway decided to bring the matter to the attention of the JCS. The withdrawals had left the theater artillery reserve in a weakened condition and, in Ridgway's opinion, had revealed the danger in accepting World War II rates of daily fire for the Korean War. World War II corps had far more artillery battalions assigned to them than did the corps in Korea and could maintain a lesser rate of fire per gun each day to carry out comparable missions successfully. With relatively fewer guns and Communist artillery strength constantly mounting, the U.S. artillery units in Korea had to fire more frequently. Ridgway argued earnestly for an increase in the day of supply for his 8-inch, 105-mm., and 155-mm. howitzers and for his 155-mm. guns, pointing out the grim relationship between artillery and casualties:

Whatever may have been the impression of our operations in Korea to date, artillery has been and remains the great killer of Communists. It remains the great saver of soldiers, American and Allied. There is a direct relation between the piles of shells in the Ammunition supply points and the piles of corpses in the graves registration collecting points. The bigger the former, the smaller the latter and vice versa.64

The increase for his heavy caliber howitzers and guns were but one part of Ridgway's request. If they were granted, he wanted to raise the reserve of these shells from 75 to 90 days as quickly as possible. He in turn would augment the supplies in Korea from 30 to 40 days and keep 20 days' supply in the pipeline leaving only 30 days' reserve in Japan.65 But even as Ridgway sent off his request, he informed Van Fleet that the Eighth Army would have to live within its ammunition income in November. Since it would take considerable time to build up the theater reserve again, "There must be no mental reservation that regardless of disapproval of subordinate commanders wishes for ammunition that such ammunition will be supplied in case stocks get low. Your ammunition resources, present and predicted, are as stated above. Their increase is beyond the capability of this theater."66

The approval of Ridgway's requests on 20 October did not, of course, produce an immediate improvement in the ammunition situation in the FEC.67 But the end of the fall campaign and the negotiation of the line of demarcation stabilized the battle line and lowered the intensity of the fighting. The possibility that an armistice might be concluded soon led Van Fleet to secure Ridgway's permission in early December to bring his ammunition level up to a forty-five day reserve rather than thirty. Van Fleet feared that the Communists might succeed in getting a clause freezing ammunition stocks at their current level written into the armistice and preferred to bolster his own before this happened.68

At the end of 1951, the ammunition tale took a new twist. The records of ammunition expenditures during the summer and fall campaigns evidently were brought to Ridgway's attention and disturbed him deeply. Although it was too late to do anything about the ammunition already spent, the Far East commander decided that the phenomenal rates of fire were due to "either extravagant waste or expenditure of ammunition, or misuse of artillery, or both." Since excessive use of artillery shells imposed heavier demands upon U.S. industry and drained raw materials, Ridgway told Van Fleet to maintain constant supervision lest the performance be repeated.69

This was a serious charge and Van Fleet was not inclined to let it pass unchallenged. He did not believe that there had been either waste or misuse of artillery and warned against rigid comparisons of World War II firings with those in Korea. "Based on World War II European standards," he went on, "I estimate that the Eighth Army is short approximately 70 battalions of field artillery. Hence, the greatly reduced intensity of field artillery battalions per mile of front, has required more rounds per individual tube to achieve the effectiveness required. The effectiveness of one volley from four battalions is far greater than four volleys from one battalion." He admitted using his artillery freely to kill the enemy during the offensives, but, taking a leaf from Ridgway's own book, he reminded the Far East commander that if he had tried to take the objectives with limited artillery fire, the casualty lists of the Eighth Army would have been materially higher. In closing, Van Fleet maintained that he kept a watchful eye on the ammunition level and that he had conserved a considerable amount of shells during the static October-December period.70

As the Ridgway-Van Fleet exchange mirrored the increasing concern in the Far East Command over the situation, supply officials in Washington offered little hope that there would be improvement in the calibers that were short until late in 1952.71 Mortar ammunition and shells for 8-inch guns and 155-mm. howitzers became less plentiful during the winter months and there was no prospect of relief in the heavy shell category in the near future.72

The time lag between obligating funds for ammunition production and the delivery of the finished shells was emphasized during early 1952. Despite the fact that billions of dollars of contracts had been let, the end result in many cases was still six months or more in the offing. In the meantime shortages in the Far East Command became more difficult to explain to Congress and the U.S. public. Although little was happening at the front in Korea and efforts were made to restrict nonessential artillery missions, General Collins felt that expenditures were still too heavy. Pointing out that two and a half billion dollars of the three and a half requested for Army procurement in fiscal year 1953 must be spent for ammunition, Collins asked Ridgway on to March to see whether major reductions should not be made at once and retained unless large-scale fighting resumed. Ridgway in turn assigned the problem to Van Fleet.73

Considering the small number of casualties inflicted upon the enemy during the early part of 1952, the Eighth Army's expenditures of artillery ammunition appeared rather high.74 But Van Fleet was quick to remind Ridgway that during the winter months, Eighth Army had used less than 60 percent of the ammunition allocated it and at present rates would expend about three-quarters of a billion dollars worth in 1952. Heavy mortar ammunition was under rigid allocation already and could not be reduced further, Van Fleet continued. If savings were mandatory, the only category that he could afford to reduce was interdictory fire. Since 66 percent of Eighth Army's missions were interdictory, as against 19 percent for counterbattery and 15 percent for meeting enemy actions, Van Fleet was ordering his corps commanders to cut interdictory fire by 20 percent, but this was as far as he could go.75

When Ridgway replied to Collins on 9 April, he had increased the estimate of ammunition costs for 1952 to slightly over one billion dollars, but after reporting the 20-percent reduction contemplated by Van Fleet in interdictory fire, Ridgway struck at the heart of the matter:

It still seems to me that the most fundamental factors in this problem are the ones most frequently obscured by the search for economies. Those factors are that we are at war in Korea, and that ammunition must be provided to meet essential requirements, both of expenditures and stock levels. Provided these requirements are reasonable, economy ceases to be a factor. The only alternative is to effect savings of dollars by expenditure of lives.76

By the end of April several facts were readily apparent. The huge ammunition stockpile left over from World War II had been a blessing and a curse. For while it had provided a substantial backlog on which the United States could draw to meet the demands of Korea, the imbalance in its stocks had gone unnoticed and the very mass of the stockpile had introduced a dangerous sense of complacency. The expectation of a short war had fostered this complacency and permitted the rebuilding of the defunct ammunition industry to be delayed. Compounding the situation, the lack of industrial mobilization that followed the outbreak of the war led to further setbacks in the battle for ammunition production. In the meantime the imbalances had come to light and, as it happened, many of these were in mortar and howitzer ammunition that were most in demand for the artillery war that set in from mid-1951on. The tremendous costs of the ammunition program that were cited in late 1951 and early 1952 reflected the decelerated pace of the war and served as an excuse for reducing the rate of expenditure of ammunition. A lower rate of daily fire in turn would help alleviate the problem of dwindling ammunition reserves in the essential categories. On the other hand, restrictions in the number of rounds that could be used each day caused the man at the front to complain and brought the whole matter to the attention of Congress and the public.

Despite the charges and countercharges in the ammunition free-for-all, the principal enemy was time. Until production could begin on a scale that would replenish stocks as well as current needs, the ammunition crises would go on. The rationing which was adopted in the winter and spring of 1952 was a temporary expedient to bridge the gap between the decreasing stockpile and new production, but until the transition was complete, shortages and expedients would be the rule.

The disadvantages of fighting even a small war without an adequate production base in being or capable of quick expansion are readily discernible in the ammunition situation of 1951 and 1952. Feeding the hungry maw of the Far East Command drained the reserves in the United States and led to reductions in allocations for the Army units in Europe. An expansion of the war might well have been catastrophic for no amount of money or effort could buy the most priceless commodity-time.

Fortunately, the Communists matched the UNC in their disinclination to press the fight on the battlefield or to broaden the war. It appeared that as long as the moderate pace of the conflict continued, U.S. ammunition supplies would be sufficient to maintain the status quo until new production took up the slack.

Propaganda Assault

The general indisposition toward combat in early 1952 confined itself wholly to the front and did not extend to the battle behind the lines for world opinion. Since words had proven themselves effective in the matter of the incidents during the summer and fall of 1951, the Communists began once again to increase the flow and intensity of their propaganda. As events at the conference table at Panmunjom revealed the basic differences in approach to the problem still outstanding, the enemy fell back upon its tried and tested method of exerting pressure upon the UNC by means of a series of new "incidents."

Although there had been several violations of the neutral zone and of the agreements made between the Communists and the UNC on convoys to the Panmunjom area, the enemy's reaction to these breaches had been mild during December and January. A B-26 light bomber had strafed a truck in the Kaesong sector on 11 December because of the pilot's navigational error and another pilot had unloaded a bomb on Kaesong on 17 January instead of dropping his pylon fuel tank. On the following day a prescheduled air strike on a bridge at Hanp'o-ri, some 18 miles north of Kaesong, caught the Communist convoy to Panmunjom as it approached the bridge and damaged one of the trucks. The enemy accepted the expressions of regret in each instance and made no attempt to use the incidents for other purposes.77

As the negotiations began to bog down over Items 3 and 4 at Panmunjom, indications of a new propaganda campaign were disclosed in February. In a United Nations meeting Soviet Delegate Jacob Malik accused the United States of using poison gas in Korea. While this was not the first time the charge had been leveled, it seemed significant that Malik had made it himself. It caused a flurry in Washington since it might be a warning that the Communists were preparing to employ gas warfare themselves. On the other hand, the enemy may have discovered that Ridgway had ordered all his commanders to organize, equip, and train their forces to defend themselves against chemical, biological, and radiological attack and deduced from this that the UNC was getting ready to introduce new forms of warfare.78 The Ridgway order was purely routine, but the enemy could not be certain of this.

At any rate the Communists evidently were taking no chances and attempted to forestall the possible use of chemical warfare. Actually the Far East Command was in no position to launch a gas attack. The theater was not permitted to stock toxic chemicals, in the first place, and there was also a shortage of over 50,000 gas masks in the Far East. Because the individual soldier in World War II had frequently been inclined to discard his gas mask, none had been issued in Korea. Instead they were stored at depots where they could be distributed within twenty-four hours.79 The absence of toxic materials in the FEC and the lack of special preparation within the theater to wage or defend against chemical warfare belied the Communist charges, but as so frequently happens, accusations, no matter how false, leave residual damage.

Before the furore over the poison gas had completely died down, the enemy opened a fullscale attack in another quarter. In late February radio broadcasts from Moscow, Peiping, and Pyongyang openly charged the United States of conducting bacteriological warfare in North Korea and Manchuria. Enemy newspapers picked up the story and related how UNC planes had dumped infected insects and materials and artillery had fired shells filled with bacterial agents into Communist areas. Complete with pictures, one article "proved" that on 17 February a UNC plane had dropped a weapon north of Pyongyang filled with hideous, infected flies that could live and fly in snowy weather.80

Intelligence reports estimated that the Communists were not only trying to discredit the United States through this campaign but also were attempting to cover up their lack of success in preventing and controlling epidemics and to whip up new enthusiasm for the Korean War in China and among Communist sympathizers throughout Asia.81 In 1951 there had been extensive typhus, cholera, typhoid, and smallpox outbreaks in North Korea and it was quite possible that the enemy expected reoccurrences and desired a scapegoat.

Despite strong and immediate denials of the use of germ warfare by Secretary of State Acheson and other officials in Washington, there was evidence that some Asian countries were lending credence to the enemy's claims. Both the State and Defense Departments began to show concern as the attack grew more intense and instructed Ridgway to do all he could in the way of categoric disavowals if the subject were brought up at Panmunjom.82 In the meantime the State Department sent an invitation to the President of the International Committee of the Red Cross in Geneva suggesting that the United States would welcome a full investigation of the Communist charges by a disinterested body to reveal the falsity of the enemy propaganda.83 The ICRC accepted the U.S. offer in mid-March, but there was little hope that the Communists would have anything to do with representatives of a committee that they regarded as an agent of the United Nations Command and not as a disinterested body.84

On 8 March Chinese Foreign Minister Chou En-lai had hinted at another facet of the antigerm campaign. In a broadcast he implied that if the Chinese caught U.S. Air Force personnel engaged in spreading disease over China, they would be treated as war criminals. The Air Force could not let this threat go unchallenged and the JCS told Ridgway to issue a strong statement holding the Communists responsible for proper treatment of prisoners of war. At the same time he could again deny the accusations and warn the enemy against using an epidemic to mask ill treatment of prisoners. Army G-3 held that this would allow the UNC to shift over to the propaganda offensive.85

As Ridgway prepared his statement, the U.N. World Health Organization volunteered to send technical assistance to North Korea to help combat disease and epidemics and the United States quickly agreed that the WHO should communicate directly with the Communists on this matter. If the enemy refused to receive WHO teams, it would tend to discredit the charges and reflect badly upon the Communist concern for the welfare of their people.86

Although the propaganda drive gathered momentum during March and April with the Communists reporting the dropping of infected spiders, fleas, beetles carrying anthrax, voles carrying plague, and even poisoned clams in North Korea and in China, the rejection of the ICRC and WHO offers to investigate the incidents and to aid in the control of disease did much to weaken the effect of the later claims.87 Besides, the Communists were about to be given a far more potent propaganda weapon as the trouble that had been simmering for months in the UNC prisoner of war camps reached the boiling stage.

Notes

1 See Chapter IV, above.

2 Msg, CINCFE to CG Eighth Army, g Sep 51, in Hq Eighth Army, Opnl Planning Files, Sep 51, Paper 9.

3 Msg, CX 50942, CINCFE to DA, 16 Sep 51, in Hq Eighth Army, Opnl Planning Files, Sep 5 1, Paper 28.

4 (1) Kenneth W. Myers, The U.S. Military Advisory Group to the ROK, Part IV, KMAG's Wartime Experiences, 11 July 1951-27 July 1953, pp. 26-27, 189. MS in OCMH. (Hereafter cited as Myers, KMAG's Wartime Experiences). (2) Memo, Jenkins for CofS, 9 Nov 51, sub: To Determine What Can be Done Now to Make Better Use of Korean Manpower, in G-3 091 Korea, 187/7.

5 Myers, KMAG's Wartime Experiences, pp. 26-27, 189.

6 Ibid., pp. 134-36.

7 Ibid., pp. 128-31.

8 Ibid.

9 Ibid., pp. 201-04.

10 (1) Ibid., pp. 174-79. (2) Memo, Jenkins for DCofS, 21 Nov 51, sub: ROKA Students . . . , in G-3 350.2 Korea, 5/16.

11 Memo, Jenkins for CofS, 9 Nov 51, sub: To Determine What Can Be Done Now to Make Better Use of Korean Manpower . . . , in G-3 091 Korea, 187/7.

12 Memo, Foster for JCS, to Nov 51, sub: Post-Hostilities Military Forces of the ROK, in G-3 091 Korea, 208.

13 See Chapter VI, above.

14 Memo, Bradley for Secy Defense, 23 Jan 52, sub: Post-Hostilities Military Forces of the ROK.

15 Msg, DA 905814, Hull to Ridgway, 9 Apr 52.

16 Msg, G 5347 TAC, Van Fleet to Ridgway, 9 Apr 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 52, an. 1, incl 18. See also Interv with General Van Fleet, in U.S. News and World Report, vol. XXXII, No. 13 (March 28, 1952).

17 Msg, CX 66647, Ridgway to Hull, 8 Apr 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 52, an. 1, incl 19.

18 Msg, C 65987, Ridgway to JCS, 27 Mar 52, DA-IN 121000.

19 Ibid.

20 COMNAVFE, Comd and Hist Rpt, Feb 52, pp. 4-2, 4-3.

21 Msg, CINCFE to DA, 18 Nov 51, DA-IN 354.

22 (1) Msg, DA 909826, G-3 to CINCFE, 27 May 52. (2) Myers, KMAG's Wartime Experience, pp. 87-96.

23 New York Times, August 24, 1951.

24 New York Times, September 21, 1951.

25 Msg, 070801 American Embassy, Pusan, to SCAP, 7 Dec 51, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Nov-Dec 51, an. 1, incl 45.

26 Msg, CX 64241, Ridgway to JCS, 25 Feb 52, DA-IN 109112

27 Msg, JCS 902158, JCS to CINCFE, 27 Feb 52. This message was drafted by the State Department and cleared with the JCS, Defense Department, and the President.

28 Msg, DA 902912 Eddleman to CINCFE, 6 Mar 52. This transmitted the Truman message to Rhee.

29 For a discussion of U.S. aid policy in Korea see Gene M. Lyons, "American Policy and the United Nations Program for Korean Reconstruction," in International Organization, vol. XII, No. 2 (1958), pp. 180-92.

30 Memo of Understanding between UNC and U.N. Korean Reconstruction Agency, 21 Dec 51.

31 Msg, CINCUNC to DA, 20 Sep 51, DA-IN 18653.

32 Msg, C 62218, Ridgway to Collins, 25 Jan 52, DA-IN 4572.

33 The legal exchange rate of 6,000 won to the dollar was not considered to be approximate to actual value of the won. In January 1952 a rate of 12,000 won to the dollar would have been closer to the actual value.

34 (1) Msg, CX 60526, CINCFE to G-3, 31 Dec 51, DA-IN 15295. (2) Msg, CINCFE to G-3, 24 Jan 52, DA-IN 4192.

35 Msg, C 63175, Ridgway to Van Fleet, 9 Feb 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Feb 52, an. 1, incl 24.

36 Charles N. Henning, Economic and Related Political Factors in Civil Affairs Operations, Republic of Korea, ORO Study T-211 (Washington: Operations Research Office, Johns Hopkins University, 1952), p. 43.

37 (1) Msg, C 6505, Ridgway to CofS, 10 Mar 52, DA-IN 114192. (2) Msg, C 65121, Ridgway to CofS, 12 Mar 52, DA-IN 115005.

38 Draft Directive, sub: Terms of Reference for the Unified Command Mission to the ROK, no date, in G-3 091 Korea, 42/11. A copy of this directive was sent to Meyer in Japan in April.

39 Ltr, Meyer to Osborn, no sub, 24 May 1952, to G-3, 091 Korea, 42/16. The United States agreed to pay $75,000,000 for the January-May 1952 period and an initial payment of $35,000,000 was made on 29 July.

40 See the text of the treaty in Department of State Bulletin, vol. XXV, No. 638 (September y, 1951) , pp. 463-65.

41 CINCFE G-3 Presentation to Asst Secy Army Alexander, no date, in G-3 091 Korea, 187/7.

42 UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Sep 51, pp, 35-36.

43 Msg, DA 89795, CofS to CINCFE, 18 Dec 51.

44 Msg, C 59752, Ridgway to JCS, 20 Dec 51, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 52, an. 4, incl 1.

45 Msg, DA 90318, CofS to CINCFE, 23 Dec 51.

46 UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Dec 51, pp. 43-44.

47 Msg, DA 902603, CofS to CINCFE, 4 Mar 52.

48 Memo, Civil Affairs Sec SCAP to CofS SCAP, 28 Feb 52, sub: Conf by SCAP with Prime Minister Yoshida, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Mar 52, an, 1, incl 11.

49 Msg, DA 902855, DA to SCAP, 7 Mar 52.

50 Msg, C 50742, CINCFE to JCS, 13 Sep 51, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Sep 51, an. 4, incl 10.

51 Msg, DA 90317, G-3 to CINCFE, 22 Dec 51.

52 (1) Msg, JCS 905965, JCS to CINCFE, 10 Apr 52. (2) Msg, JCS 907213, JCS to CINCFE, 25 Apr 52.

53 See text of Administrative Agreement of 28 February 1952, in Dept of State Bulletin, vol. XXVI, No. 663 (March 10, 1952) , pp. 383ff.

54 (1) Msg, C 66619, CINCFE to JCS, 9 Apr 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 52, an. 1, incl 12. (2) Msg, C 67740, Ridgway to DA, 29 Apr 52, DA-IN 133087.

55 Hearings Before the Preparedness Subcommittee No. 2 of the Committee on Armed Services, U.S. Senate, 83d Congress, 1st session, on Ammunition Shortages in the Armed Services, 1953.

56 The following summary is based upon the excellent study made by the former Deputy Assistant Chief of Staff, G-4, Maj. Gen. William O. Reeder, after the war was over, and entitled: The Korean Ammunition Shortage. Copy in OCMH files.

57 It should be noted that small arms ammunition was always plentiful and caused no concern.

58 The day of supply was based upon World War II experience.

59 The reserve was computed by multiplying the day of supply by the number of guns on hand and then multiplying the result by seventyfive days, which was the safety-level factor in case deliveries should be halted or cut off for a period.

60 Williamson et al., "Bloody Ridge," ch. V Aug-Sep 51, pp. 27-28.

61 Hq Eighth Army, Comd Rpt, Sep 51, sec. I, Narrative.

62 Williamson et al., Action on "Heartbreak Ridge," p. 32.

63 U.S. I Corps, Comd Rpt, Oct 51, sec. I, pp. 63, 75.

64 Msg, CX 58171, CINCFE to JCS, 17 Oct 51, in FEC G-3 471 Ammunition.

65 Ibid.

66 Msg, CX 58155, CINCFE to CG EUSAK, 17 Oct 51, in Hq Eighth Army Opnl Planning Files, Oct 51, p. 17. The Department of the Army daily rate authorized was: 50 rounds of 150-mm., 33 rounds of 155-mm., and 20 rounds of 8-inch howitzer shells. Ridgway had asked that these be raised to 55, 40, and 50, respectively.

67 Msg, DA 84571, DA to CINCFE, 20 Oct 51.

68 UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Nov-Dec 51, CofS sec., an. 1, p. 8.

69 Msg, C 60169, Ridgway to Van Fleet, 26 Dec 51, in FEC G-3 471 Ammunition.

70 Msg, G 3789 TAC, Van Fleet to Ridgway, 29 Dec 51, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Nov-Dec 51, CinC and CofS sec., an. 1, incl 12.

71 Memo, Magruder (G-4) for ACofS G-3, 28 Dec 51, sub: Augmentation from FEC, in G-3 320.2 Pacific, 79/1.

72 Memo, Col Davidson, G-3, for Asst CofS G-3, 29 Feb 52, sub: Rpt of Staff Visits During Period 23 Jan-19 Feb 52, in G-9 333 Pacific, 1.

73 (1) Msg, DA 903815, Collins to Ridgway, 10 Mar 52. (2) Msg, C 66253, Ridgway to Van Fleet, 2 Apr 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 52, an, 1, incl 8.

74 In January 1952, FEC expended 57,000 tons of ammunition costing about $114,000,000. Estimated enemy casualties were about 20,000, so that each enemy casualty on the average took $5,800 worth of ammunition before he was injured or killed. See Check Sheet, EKW [Wright] for CofS, 31 Mar 52, FEC G-3 471 Ammunition.

75 Msg, G 5322 TAC, Van Fleet to Ridgway, 7 Apr 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 52, an. 1, incl 9.

76 Msg, C 66608, CINCFE to Collins, 9 Apr 52, in UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 52, an. 1, incl 10.

77 (1) Msg, HNC 535, Joy to CINCUNC, 11 Dec 51, in FEC Msgs, Dec 51. (2) Liaison Officers Mtg at Panmunjom, 23 Jan 52, in G-g Liaison Officers Mtg at Panmunjom, bk. II, 1952.

78 UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Nov 51.

79 Check Sheet, JHR [Col Jacquard H. Rothschild] to G-3, 9Feb 52, sub: Questions Arising From Statement Made By Soviet Delegate Malik Before U.N., in FEC G-3 471.6 Bombs, etc.

80 UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Mar 52, p. 31. For an interesting discussion of the germ warfare charges of this period, see John Clews, The Communists' New Weapon- Germ Warfare (London: Lincoln Pragers, 1953) . See also the statement of U.S. Representative to the UN Assembly, Ernest A. Gross, 27 March 1953 and 8 April 1953, in Dept of State Bulletin, vol. XXVIII, No. 722 (April 27. 1953)

81 UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Mar 52, p. 32.

82 Msg, JCS 903060, JCS to CINCFE, 7 Mar 52.

83 (1) Msg, DA 903096, G-3 to CINCFE, 8 Mar 52. (2) Msg, C 64368, CINCFE to DA, 9 Mar 52, DA-IN 114029.

84 Msg, JCS 903547, JCS to CINCFE, 14 Mar 52.

85 (1) Memo, Eddleman for CofS, 11 Mar 52, sub: Chinese Communist Threat . . . , in G-3 385, 8. (2) Msg, JCS 903686, JCS to CINCFE, 15 Mar 52. This message was drafted by the Air Force and cleared by the JCS, Defense and State Departments, and the President.

86 (1) Msg, C 65348, Ridgway to JCS, 16 Mar 52, DA-IN 116709. (2) Msg, JCS 903780, JCS to CINCFE, 17 Mar 52.

87 (1) UNC/FEC, Comd Rpt, Apr 52, p. 24. (2) Clews, The Communists' New Weapon- Germ Warfare, pp. 14-24.