Redeployment South

The Chinese did not pursue the Eighth Army's twenty-mile withdrawal from the Ch'ongch'on to the Sukch'on-Sunch'on-Songch'on line. Only light enemy patrolling occurred along the new line on 1 December, mostly at its eastern end where there had been no deep withdrawal the day before. General Walker nevertheless believed that the Chinese would soon close the gap, resume their frontal assaults, and again send forces against his east flank.1

Walker now estimated the Chinese opposing him to number at least six armies with eighteen divisions and 165,000 men. Of his own forward units, only the 1st Cavalry; 24th, 25th, and ROK 1st Divisions; and the two British brigades were intact. The ROK 6th Division could be employed as a division but its regiments were tattered; about half the ROK 7th and 8th Divisions had reassembled but were far less able than their strengths indicated; and both the 2d Division and Turkish brigade needed substantial refurbishing before they could again function as units. Of his reserves, the four ROK divisions operating against guerrillas in central and southern Korea were too untrained to be trustworthy on the line. His only other reserves were the 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team and its attached Filipino and Thai battalions then guarding forward army supply installations; the Netherlands battalion, which had just completed its processing at the U.N. Reception Center; and an infantry battalion from France, which had just debarked at Pusan.2

By Walker's comparison of forces, the injured Eighth Army could not now set a successful static defense. Considering delaying action to be the only course open, a course in which he should not risk becoming heavily engaged and in which he should anticipate moving out of Korea, Walker began to select delaying lines behind him. He intended to move south from one to the next well before his forces could be fixed, flanked, or enveloped.3

Though the XIII Army Group remained out of contact on 2 December, Walker received agent and aerial observer reports that Chinese were moving into the region east of Songch'on and that either they or North Korean guerrillas infesting that area had established blocking positions below the Pyongyang-Wonsan road from Songch'on eastward twenty-five miles to Yangdok. They could be trying to secure a portion of the lateral route in advance of a drive toward either or both coasts, and should the drive go west into P'yongyang, they could trap the Eighth Army above the city. In view of the latter possibility, Walker elected to withdraw before the thrust materialized. Pyongyang was to be abandoned.4

Walker's use of relatively slight intelligence information in deciding to withdraw below P'yongyang reflected the general attitude of the Eighth Army. According to some accounts, Walker's forces had become afflicted with "bugout fever," a term usually used to describe a tendency to withdraw without fighting and even to disregard orders.5 Because it implied cowardice and dereliction of duty, the term was unwarranted. Yet the hard attacks and high casualties of the past week and the apparent Chinese strength had shaken the Eighth Army's confidence. This same doubt had some influence on Walker's decision to give up P'yongyang and would manifest itself again in other decisions to withdraw. But the principal reason for withdrawing had been, was, and would continue to be the constant threat of envelopment from the east.

Pyongyang Abandoned

As Walker started his withdrawal from the Sukch'on-Sunch'on-Songch'on line on 2 December, Maj. Gen. Doyle O. Hickey, acting chief of staff of the Far East Command and United Nations Command, arrived with word from General MacArthur that, in effect, allowed Walker to leave behind any equipment and other materiel that he chose as long as they were destroyed.6 Walker, however, planned not to drop behind P'yongyang until the army and air force supply points in the city had been emptied and the port of Chinnamp'o cleared. To provide time for the removal he ordered a half step to the rear, sending his forces south toward a semicircular line still twenty miles above P'yongyang. (Map 13) While service troops rushed to evacuate supplies and equipment from the North Korean capital and port, line units reached the temporary line late on the 3d with no enemy interference beyond being harassed by North Korean guerrillas on the east flank.7

Walker meanwhile pushed reserves eastward onto Route 33, the next P'yongyang-Seoul road inland from Route 1, to protect his east flank and to guarantee an additional withdrawal route below the North Korean capital. He deployed the 24th Division at Yul-li, twenty-five miles southeast of Pyongyang, and the partially restored ROK II Corps at Sin'gye in the Yesong River valley another thirty miles to the southeast. South and east of Sin'gye, units of the ROK 2d and 5th Divisions previously had occupied Sibyon-ni and Yonch'on on Route 33, P'och'on on Route 3, and Ch'unch'on on Route 17 in the Pukhan River valley during antiguerrilla operations. Route 33 thus was protected at important road junctions, and Walker at least had the semblance of an east flank screen all the way from Pyongyang to Seoul.8

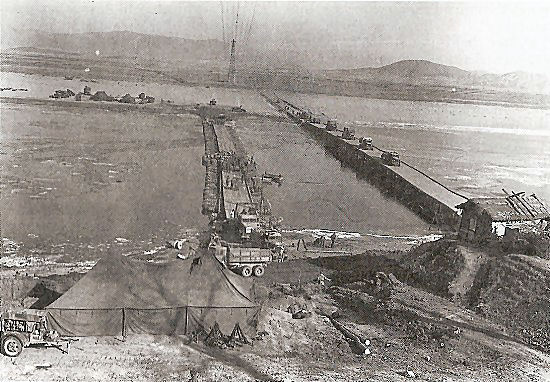

8th Army Troops Retreating South From Sunch'on Toward P'yongyang

Walker moved the damaged 2d Division from Chunghwa into army reserve at Munsan-ni on the Imjin River twenty-two miles north of Seoul, where General Keiser, with priority on replacements, was to rebuild his unit. But while Keiser's immediate and main task was to revive the 2d Division, Walker wanted him also to reconnoiter as far as Hwach'on, more than fifty miles east of Munsan-ni, in case it became necessary to employ 2d Division troops in those areas guarded by South Korean units of doubtful ability. Walker attached the Turkish brigade to the 2d Division. Hurt less by casualties than by disorganization and equipment losses, the Turks had collected bit by bit at several locations, mostly at Pyongyang. On 2 December, after General Yasici had recovered some thirtyfive hundred of his original five thousand men, Walker ordered the brigade to Kaesong, fifteen miles north of Munsan-ni, to complete refurbishing under General Keiser's supervision as more of its members were located and returned.9

Map 13. Eighth Army Withdrawal, 1-23 December 1950

Walker held the 187th Airborne Regimental Combat Team and its attachments in the Pyongyang area to protect his supply routes and installations. In preparation for the coming withdrawal south of the city, the airborne troops also were to keep civilians from moving over four ponton bridges spanning the Taedong River, two inside Pyongyang and another pair three miles east of the city, and to take whatever other precautions were necessary to insure an uninterrupted flow of military traffic over the crossings.10

On 3 December, after receiving more reports of sizable enemy movements and concentrations east and northeast of the Eighth Army position, Walker anticipated not only a westward enemy push into P'yongyang but also a deeper thrust southwest through the Yesong valley and across the army withdrawal routes in the vicinity of Sin'gye. Induced to haste by this possibility, he ordered his line units to drop fifteen miles behind Pyongyang beginning on the morning of the 4th, to a line curving eastward from Kyomip'o on the lower bank of the Taedong to a point short of Koksan in a subsidiary valley of the upper Yesong River. Walker warned them to be ready to withdraw another fifty miles on the west and twenty miles on the east to a line running from Haeju on the coast north-eastward through Sin'gye, then eastward through Ich'on in the Imjin River valley. The latter withdrawal would set Walker's rightmost units athwart the Yesong valley in fair position to delay an enemy strike through it and would eliminate concern for the army left flank, which, after the initial withdrawal below P'yongyang, would open on the large Hwanghae peninsula southwest of Kyomip'o.11

In withdrawing south of Pyongyang, the IX Corps, now with the 24th Division attached, was to move on Route 33, occupy the right sector of the new army front, and reinforce the weak ROK II Corps in protecting the army east flank in the Yesong valley. The I Corps was to withdraw to the west sector of the new line over Route 1 and, while passing through P'yongyang, destroy any abandoned materiel found within the city.12

General Milburn's demolition assignment was likely to be sizable. Aside from organizational and individual equipment lost by the line units, the only notable materiel losses since the Chinese opened their offensive had been fourteen hundred tons of ammunition stored at Sinanju and five hundred tons at Kunu-ri. But now Walker's forces were about to give up the locale of the Eighth Army's main forward stockpiles, and although the smaller stores at Chinnamp'o might be evacuated, it was less likely that the larger quantities brought into Pyongyang over the past several weeks could be completely removed on such short notice. The improbability of clearing the Pyongyang stocks was increased by the necessity to give priority on locomotives to trains carrying casualties and service units, by heavy demands on trucks for troop movements as well as for hauling materiel from supply point to railroad yard, and by the problems of loading and switching trains in congested yards that earlier had been severer damaged by UNC air bombardment. 13

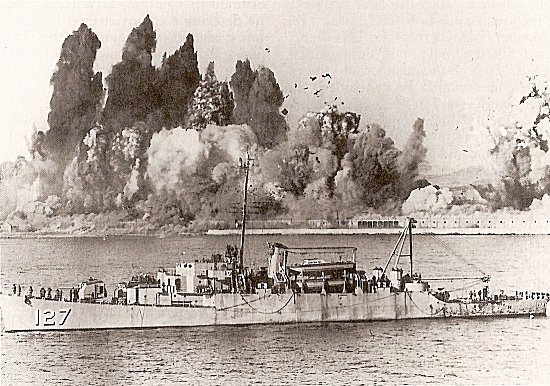

All Bridges Across The Taedong River at Pyongyang Were Destroyed After 8th Army Retreated South Of City

With almost no enemy contact, Walker's forces moved south of P'yongyang within twenty-four hours. Much of the city was afire by 0730 on 5 December when the rear guards destroyed the last bridges over the Taedong and set off final demolitions in the section of P'yongyang below the river. Colonel Stebbins, Walker's G4 who supervised the removal of materiel from Chinnamp'o and P'yongyang, would have preferred a slower move by seventy-two or even forty-eight hours. Given that additional time, Stebbins believed, the service troops could have removed most of the eight to ten thousand tons of supplies and equipment that now lay abandoned and broken up or burning inside Pyongyang. More time also could have prevented such oversights as leaving at least fifteen operable M-46 tanks aboard flatcars in the railroad yards in the southwestern part of the city. Fifth Air Force planes struck these overlooked tanks on 6 December, but differing pilot claims left obscure the amount of damage done.14

Although Chinnamp'o was exposed after early morning of the 5th, evacuation of the port continued until evening without harassment from enemy forces. Pressed only by time and the wide range of the Yellow Sea tides, the port troops from 2 through 5 December loaded LSTs, transports of the Japanese merchant marine, a squadron of U.S. Navy troop and cargo transports, and at least a hundred Korean sailboats. Aboard these craft went casualties, prisoners, and materiel sent from P'yongyang; the supplies and equipment on the ground around the port; the port service units themselves; and some thirty thousand refugees (most of them on the sailboats). Four American destroyers took station off Chinnamp'o, and aircraft from the British carrier Theseus appeared overhead on the 5th to protect the final outloading. That morning the port commander received word from Colonel Stebbins to get the last ships under way on the favorable tide at 1700. The last three ships pulled away from the docks near that hour. Demolition crews set off their last explosives, and shortly afterward the last men ashore drove an amphibious truck out to a waiting ship. Some two thousand tons of supplies and a few items of port equipment, small amounts by comparison with the losses at P'yongyang, had had to be destroyed for lack of time to remove them.15

The men and materiel sea lifted from Chinnamp'o were landed either at Inch'on (port personnel, rations, and petroleum products) or Pusan (patients, prisoners, and remaining supplies). Most of the stock evacuated from P'yongyang was shipped to depots at Kaesong and around Seoul. Some was kept forward aboard the railcars on which it had been loaded to institute a mobile system of meeting day-to-day requirements of the line units. These daily needs, mostly rations and petroleum products, were to be issued from the cars at railheads whose locations could be changed as rapidly as the line units withdrew. This system would reduce the likelihood of further materiel losses.16

The trace of the new army position vaguely resembled a question mark. I and IX Corps defenses between Kyomip'o and Yul-li formed the upper arc, IX Corps positions on the east flank from Yul-li southeastward to Sin'gye shaped the shank, and clumps of army reserves below Sin'gye supplied several dots. The figure traced was appropriate since Walker now had been out of meaningful contact with enemy forces for five days, had no clear idea of the location or movement of the main Chinese body, and could only speculate on what the XIII Army Group commander could or intended to do next.17

In an attempt to fill the intelligence gap deriving from the withdrawals and the Chinese slowness to follow, Walker on the 5th ordered General Milburn and General Coulter to send strong reconnaissance patrols, including tanks, north as far as the Taedong River. But only the 1st Cavalry Division reported any noteworthy deep patrolling, on 6 December when two battalions sortied northeast up the Yesong valley and into Kokson, where they fought a minor skirmish with North Korean troops, and on 7 December when two companies made another, but uneventful, visit to the town.18

Most of Walker's information continued to come from agents and aerial observers. The latter reported on the 6th that enemy troops were moving into Chinnamp'o and south across the Taedong estuary by ferry to the Hwanghae peninsula. Agents on the same day verified the presence of Chinese troops in Pyongyang and reported that North Korean regulars were joining North Korean guerrillas, to the east and right rear of the Eighth Army. To escape the trouble these reports portended, Walker instructed his forward units to withdraw on 8 December to the HaejuSin'gye-Ich'on line and to extend that line east to Kumhwa. The west flank would again be anchored on the sea, and Walker's forces would be able to present a front instead of a flank to the North Korean units reported gathering on the east.19

But what now worried Walker most were the whereabouts and intentions of the Chinese he previously had suspected were maneuvering into attack position just beyond his east flank. Because his forces at no time since 30 November had captured or even sighted a Chinese soldier during the sporadic encounters along the army right, he was beginning to believe that all enemy troops immediately east of him were North Korean. Chinese forces, then, possibly were moving south, not into position for a close-in envelopment but around the Eighth Army some distance to the east through the X Corps' rear area. Since General Almond's forces were concentrating at Hamhung and Hungnam far to the northeast, any such march by the Chinese would be unopposed, and if the Chinese moved through the open area in strength, they possibly could occupy all of South Korea with little or no difficulty. Walker anyway granted the Chinese this capability and against the possibility of such a sweep took steps on 6 December to deploy troops across the entire peninsula. He planned no static defense. His concept of fighting a delaying action without becoming heavily engaged remained unchanged except that he now would delay from preselected lines stretching coast to coast.20

As a preliminary, Walker obtained General MacArthur's agreement to erase the southern segment of the Eighth Army-X Corps boundary so that the Eighth Army's sector spanned the peninsula below the 39th parallel, more generally south of a line between Pyongyang and Wonsan. He also arranged air and naval surveillance of the east coast south of the X Corps' position to detect enemy coastal movements while he was extending his line. He chose coast-to-coast positions running from the mouth of the Yesong River, almost forty miles behind Haeju, northeastward through Sibyon-ni, southeastward through Ch'orwon and Hwach'on, then eastward to Yangyang on the Sea of Japan. This line, later designated line A, was roughly a hundred fifty miles long and at its most northerly point reached just twenty miles above the 38th parallel. Walker ordered five South Korean divisionsthe two of the ROK II Corps and three others then in central and southern Korea-to occupy the eastern half of the line and to start moving into position immediately. The I and IX Corps, scheduled eventually to man the western portion of line A, remained for the time being under orders to withdraw only as far as the Haeju-Kumhwa line.21

CINCUNC Order Number 5

The apprehensions evident in Walker's appraisals and plans were apparent in Tokyo as well. General MacArthur, although his main intention may have been to coax reinforcement, already had notified the Joint Chiefs of Staff that the United Nations Command was too weak to make a successful stand when he informed them on 28 November that he was passing to the defensive. The Joint Chiefs fully approved MacArthur's adoption of defensive tactics but were not convinced that a successful static defense was impossible. They suggested that MacArthur place the Eighth Army in a continuous line across Korea between Pyongyang and Wonsan. MacArthur objected, claiming such a line was too long for the forces available and that the logistical problems posed by the high, road-poor mountains then separating the Eighth Army and X Corps were too great. By concentrating the X Corps in the Hamhung area, MacArthur countered, he was creating a "geographic threat" to enemy lines of communication that made it tactically unsound for Chinese forces to move south through the opening between Walker and Almond. In any event, he predicted, the Chinese already arrayed against the Eighth Army would compel it to take a series of steps to the rear.22

The Joint Chiefs of Staff disagreed that the X Corps' concentration at Hamhung would produce the effect MacArthur anticipated. In their judgment, the Chinese already had demonstrated a proficiency for moving strong forces through difficult mountains, and the concentration of the X Corps on the east coast combined with the predicted further withdrawals of the Eighth Army would only widen the opening through which the Chinese could move. They again urged MacArthur to consolidate the Eighth Army and X Corps sufficiently to prevent large enemy forces from passing between the two commands or outflanking either of them. But MacArthur defended his view of a P'yongyang-Wonsan line, pointing out that he and Walker already had agreed that Pyongyang could not be held and that the Eighth Army probably would be forced south at least as far as Seoul. Turning his reasoning in support of a request for ground reinforcements "of the greatest magnitude," he emphasized on 3 December that his present strength would allow him at most to prolong his resistance to the Chinese by making successive withdrawals or by taking up "beachhead bastion positions" and that a failure to receive reinforcements portended the eventual destruction of his command.23

The response to MacArthur's estimate was as gloomy as his predictions. Prompted by earlier dismal reports to visit the Far East for a firsthand appraisal, Army Chief of Staff General Collins informed MacArthur on 4 December that no reinforcement in strength, at least in the near future, was possible. The remaining joint Chiefs meanwhile replied from Washington that preservation of the U.N. Command was now the guiding consideration and that they concurred in the consolidation of MacArthur's forces into beachheads.24

Beachhead sites that in varying degrees could facilitate a withdrawal from Korea were Hungnam and Wonsan for the X Corps, Inch'on and Pusan for the Eighth Army. General Collins, while touring Korea between 4 and 6 December, heard General Walker and General Almond on the best beachheads and on how best to handle their respective commands. Almond believed that he could hold Hungnam indefinitely and wanted to stay there out of certainty that by doing so he could divert substantial Chinese strength from the Eighth Army front. Walker, on the other hand, believed the preservation of the Eighth Army required a deep withdrawal. Walker attempted to forestall any order to defend Seoul, insisting that tying his forces to the ROK capital would only allow the Chinese to encircle the Eighth Army and force a slow, costly evacuation through Inch'on. He favored pulling back to Pusan, where once before he had broken an enemy offensive and where now, if reinforced by the X Corps, the Eighth Army might hold out indefinitely.25

MacArthur's G-3, General Wright, meanwhile recommended Pusan as the best beachhead for both the Eighth Army and X Corps on grounds that should UNC forces be compelled to leave Korea, they should leave the distinct impression of having delayed the enemy as long and as well as possible. Wright also pointed out that defending successive lines into the southeastern tip of the peninsula would afford UNC air forces the greatest opportunity to hurt the Chinese; further, if a withdrawal from Korea became necessary during the remaining winter months, MacArthur's command could escape extreme weather conditions at Pusan; finally, an evacuation at any time could be effected faster through the Pusan facilities than through any other port. To permit the longest delaying action possible and to enable an evacuation from the best port, Wright recommended that the X Corps be sea lifted from Hungnam as soon as possible and landed in southeastern Korea, that the X Corps then join the Eighth Army and pass to Walker's command, and thereafter that the U.N. Command withdraw through successive positions, if necessary to the Pusan area.26

On 7 December in Tokyo, Generals MacArthur, Collins, and Stratemeyer, Admirals Joy and Struble, and Lt. Gen. Lemuel C. Shepherd, the commander of all Marine forces in the Pacific, considered the various views generated during the week past and agreed on plans that embodied in largest part the recommendations of General Wright. MacArthur set these plans in effect on the 8th in CINCUNC (Commander in Chief, United Nations Command) Order Number 5. He listed nine lines to be defended by the Eighth Army, the southernmost based on the Naktong River in the general trace of the old Pusan Perimeter. But he insisted that Walker not surrender Seoul until and unless an enemy maneuver unquestionably was about to block the Eighth Army's further withdrawal to the south. Related to this stipulation, four lines lay above Seoul, the last of which, resting on the Imjin River in the west and extending eastward to the coast, was MacArthur's first delineation of positions across the entire peninsula. Here the peninsula was somewhat narrower than in the PyongyangWonsan region and offered a road net that could accommodate supply movements.27 Earlier pessimistic reports to Washington notwithstanding, MacArthur apparently believed that the Eighth Army and the X Corps combined could man this line; indeed, he expected Walker to make an ardent effort to hold it.

Through correspondence and interviews, MacArthur meanwhile had responded publicly to charges appearing in a substantial segment of the press that he was responsible for the reverse his forces were suffering at the hands of the Chinese. In defense of his strategy and tactics, he insisted that his command could not have fought more efficiently given the restrictions placed upon it by the policy of limiting hostilities to Korea. This criticism of administration policy rankled President Truman, particularly because MacArthur voiced it publicly and frequently enough to lead "many people abroad to believe that our government would change its policy."28 Truman issued instructions on 5 December by which he intended to insure that information made public by an executive branch official was "accurate and fully in accord with the policies of the United States Government."29 Specifically applicable to General MacArthur, "Officials overseas, including military commanders, were to clear all but routine statements with their departments, and to refrain from direct communication on military or foreign policy with newspapers, magazines or other publicity media in the United States."30 The Joint Chiefs of Staff forwarded the president's instructions to MacArthur on 6 December.

Withdrawal to Line B

On 7 December General MacArthur had radioed a warning to both Walker and Almond of the next day's order for successive withdrawals, the defense of Seoul short of becoming entrapped, and the assignment of the X Corps to the Eighth Army. So guided, Walker on the 8th laid out line B, which duplicated line A eastward from Hwach'on but in the opposite direction fell off to the southwest to trace the lower bank of the lmjin and Han rivers, some twenty miles behind the Yesong River. This line was at least twenty miles shorter than line A, fairly coincided with the northernmost coast-to-coast line designated by MacArthur, and now became the line toward which Walker began to move his forces for the defense of Seoul.31

On 11 December MacArthur made his first visit to Korea since he had watched the start of what was hoped would be the Eighth Army's final advance. He was now on the peninsula for a firsthand view of the Eighth Army and X Corps after their setbacks at the hands of the Chinese and for personal conferences with Walker and Almond on the steps the two line commanders had taken or planned to take in carrying out the maneuvers and command change he had ordered three days before.

When MacArthur reached Walker's headquarters (having first stopped in northeastern Korea to confer with General Almond), he was able to see not only the Eighth Army plan for withdrawing to line B but also Walker's plans in case the Eighth Army again was squeezed into the southeastern corner of the peninsula. Reviving an unused plan developed by the Eighth Army staff in September, Walker reestablished not only the Naktong River defenses but also three lines between the old perimeter and Pusan, each arching between the south coast and east coast around the port. Nearer Pusan, the Davidson line curved northeastward sixty-eight miles from a south coast anchor at Masan; next southeast, the Raider line stretched fortyeight miles from the south coast resort town of Chinhae; and just outside the port, the Pusan line arched twenty-eight miles from the mouth of the Naktong. Walker instructed General Garvin to fortify these lines using Korean labor and all other means and manpower available within Garvin's 2d Logistical Command.32

On the day following MacArthur's visit Walker established two more lettered lines. Line C followed the lower bank of the Han River just below Seoul, curved northeast to Hongch'on, thirty miles below Hwach'on, then reached almost due east to the coast at Wonpo-ri, fifteen miles behind Yangyang. Line D, next south, ran from a west coast anchor fortyfive miles below Seoul northeast through the towns of Py'ongt'aek, Ansong, Changhowon-ni, and Wonju to Wonpo-ri, the same east coast anchor as for line C. These lines were to be occupied if and when enemy pressure forced the Eighth Army to give up Seoul but before any deep withdrawal as far as the Naktong was required.33

Amid this contingency planning and through 22 December Walker gradually pulled his forward units south and pushed ROK forces north into positions generally along line B. The I and IX Corps, withdrawing over Routes 1 and 33, bounded in three-day intervals through the Haeju-Kumhwa line and line A toward sectors along the western third of line B. The withdrawal was uncontested except for minor encounters with North Korean troops on the IX Corps' east flank, but thousands of refugees moving with and trailing the two corps had to be turned off the main roads lest they block the withdrawal routes. By 23 December both corps occupied stable positions in their new sectors. The I Corps, with two divisions and a brigade, stood athwart Route I along the lower banks of the Han and the lmjin; the IX Corps, with two divisions, blocked Routes 33 and 3 right at the 38th parallel.34

Spreading ROK forces along the remainder of the line proved more frustrating. Transportation requirements exceeded available trucks; resistance from North Korean troops in the central region slowed the South Koreans; and general confusion among the sketchily trained ROK units caused further delay. But by 23 December General Walker managed to get the ROK III Corps up from southern Korea and, with three divisions, emplaced in a central sector adjoining the IX Corps on the east. The South Korean front lay below line B, almost exactly on the 38th parallel, with its center located about eight miles north of Ch'unch'on. In more rugged ground next east, the ROK II Corps occupied a narrow one-division front astride Route 24, which passed southwestward through the Hongch'on River valley. The corps thus blocked what otherwise could provide enemy forces easy access south through central Korea over Route 29 and to lateral routes leading west to the Seoul area.35

By 20 December the ROK I Corps had been sea lifted in increments out of northeastern Korea, landed at Pusan and near Samch'ok close to the east coast anchor of line B, and transferred to Eighth Army control. Walker immediately committed the additional corps to defend the eastern end of the army line. By the 23d the ROK I Corps, with two divisions, occupied scattered positions blocking several mountain tracks and the east coast road.36

Regardless of his success in stretching forces across the peninsula, Walker lacked confidence in the line he had built. His defenses were shallow and there were gaps. He mainly mistrusted the ROK forces along the eastern two-thirds of the line. He doubted that they would hold longer than momentarily against a strong enemy attack, and, should they give way, his forces above Seoul in the west would be forced to follow suit. It was to meet this particular contingency that he had established lines C and D on 12 December. On the 15th he extended his effort by dispatching the 1st Cavalry Division out along the connected Routes 2-18-17 northeast of Seoul as added protection against any strike at the capital city from the direction of Ch'unch'on.37

Eighth Army Troops Dig In North Of Seoul

The same day, he started army headquarters, less a small group to remain in Seoul, south to Taegu. He already had directed the removal of major supply stores located in or above Seoul to safer positions below the Han River and had ordered the reduction of stocks held in the Inch'on port complex. On the 18th he assigned corps boundaries along line C and described the deployment of army reserve units to cover a withdrawal to this first line below Seoul. Two days later he ordered the still-weak 2d Division, which by then had stepped back from Munsan-ni to Yongdungp'o, a suburb of Seoul just below the Han, to move to the town of Ch'ungju, some sixty miles southeast of Seoul. From there the division was to be ready to move against any enemy force breaking through South Korean lines in central or eastern Korea and was to protect the flank of Walker's western forces in any withdrawal prompted by such an enemy thrust. General Keiser in the meantime had been evacuated because of illness, and Maj. Gen. Robert B. McClure now commanded the 2d Division.38

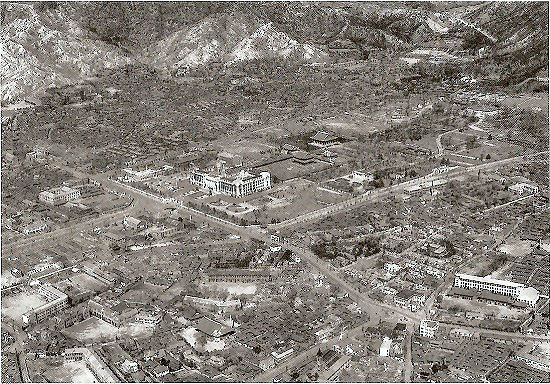

Seoul: The Capitor Is At Center

To General MacArthur, the elaborate preparations for a withdrawal below Seoul indicated that Walker had decided against a determined defense of the city. When MacArthur raised the question, Walker assured him that he would hold Seoul as long as he could. But, Walker pointed out, sudden collapses of ROK forces twice before had placed the Eighth Army in jeopardy. Nor had the ROK Army shown any increased stability even after strenuous efforts to improve it. If, as he suspected, the ROK units now along the eastern two-thirds of line B failed to stand against an attack, his positions north of Seoul could not be held and the then-necessary withdrawal would have to be made over an obstacle, the Han River. In Walker's mind these two dangers, of another sudden ROK Army collapse and of making a river crossing in a withdrawal, made his extensive preparations a matter of "reasonable prudence."39

Walker also was convinced that his adversaries were now capable of opening an offensive at any time. He still had no solid contact with enemy forces, but by pressing intelligence sources over the previous two weeks he had obtained sufficient evidence to predict an imminent attack and to forecast the strength, paths, objective, and even possible date of the next blow.40

Between 8 and 14 December Walker caught a southeastward shift of the North Korean II Corps, the bulk of which previously had been concentrated in and operating as a guerrilla force out of the mountains between Koksan and Inch'on. Apparently having retaken regular status, the corps paralleled the Eighth Army's southeastern withdrawals below P'yongyang. As Walker's forces spread out along line B, the North Korean unit followed suit, occupying positions just above the 38th parallel in the central sector, principally between Yonch'on in the Wonsan-Seoul corridor and Hwach'on, due north of Ch'unch'on. It also seemed that earlier reports of reconstituted North Korean units joining the II Corps were correct. Several renewed North Korean divisions apparently had assembled immediately behind the II Corps to make a total strength of sixty-five thousand plausible for the North Korean troops directly opposite the Eighth Army's central sector as of 23 December.41

As late as 17 December Walker was still completely out of contact with Chinese forces and by the 23d had encountered only a few, these in the I and IX Corps sectors in the west. General Partridge, who had shifted the emphasis of Fifth Air Force operations to armed reconnaissance and interdiction about the time Walker had given up P'yongyang, was able to verify that Chinese forces had moved south in strength from the Ch'ongch'on battlefields, but not how far.42 Until mid-December his fighter pilots and light bomber crews discovered and attacked large troop columns moving openly in daylight over main and secondary roads between the Ch'ongch'on and P'yongyang. But then, to escape Partridge's punishing attacks, the Chinese reverted to their strict practices of concealment and camouflage and halted virtually all daytime movement.43

Walker, consequently, had no clear evidence that the main body of the XIII Army Group had moved any farther south than P'yongyang. But on the basis of repeated reports from agents and air observers that Chinese troops and supplies were moving southeastward from the North Korean capital, by the 23d he considered it possible that three or four Chinese armies with about a hundred fifteen thousand troops were bunched within a day's march of the Eighth Army's central front. This possibility brought the estimate of enemy strength above Walker's central positions to a hundred eighty thousand. Furthermore, Walker judged, these troops could be reinforced by any units of the XIII Army Group remaining in the P'yongyang area within four to eight days and by the Chinese and North Korean units currently operating in the X Corps sector within six to ten days.44

To Walker, the apparent concentration and disposition of enemy forces opposite his central front clearly suggested offensive preparations in which the North Korean II Corps was screening the assembly of assault forces and supplies. Small North Korean attacks below Yonch'on and from Hwach'on toward Ch'unch'on seemed designed to search out weaknesses in the Eighth Army line in those areas and indicated the possibility of a converging attack on Seoul south along Route 33 and southwest over the road from Ch'unch'on. A likely date for opening such an attack, because of a possible psychological advantage to the attackers, was Christmas Day.45

Walker's largest hope of holding Seoul for any length of time in these circumstances rested on the arrival of the remainder of the X Corps from northeastern Korea. Once he had General Almond's forces in hand, Walker planned to insert them in the Ch'unch'on sector now held by the untried ROK III Corps. This move would place American units athwart the Ch'unch'on-Seoul axis, one of the more likely enemy approaches in an attack to seize the South Korean capital. Whether the X Corps would be available soon enough depended first on how closely Walker had estimated the opening date of the threatening enemy offensive and second on how long it would take General Almond to get his forces out of northeastern Korea and to refurbish them for employment under the Eighth Army.46

The X Corps Evacuates Hungnam

By the time General Almond received General MacArthur's 8 December order to evacuate the X Corps through Hungnam, two sideshows to the coming main event were well under way. Out of the earlier decision to concentrate X Corps forces at Hungnam, the evacuation of Wonsan had begun on 3 December. In a week's time, without interference from enemy forces, the 3d Division task force and a Marine shore party group totaling some 3,800 troops loaded themselves, 1,100 vehicles, 10,000 tons of other cargo, and 7,000 refugees aboard transport ships and LSTs provided by Admiral Doyle's Task Force 90. One LST sailed north on the 9th to Hungnam, where its Marine shore party passengers were to take part in the forthcoming sea lift. The remaining ships steamed for Pusan on the 9th and 10th.47

The Task Force 90 ships dispatched to Songjin on 5 December to pick up the tail-end troops of the ROK I Corps meanwhile had reached their destination and by noon on 9 December had taken aboard the ROK 3d Division (less the 26th Regiment, which withdrew to Hungnam as rear guard for the 7th Division); the division headquarters, division artillery, and 18th Regiment of the ROK Capital Division; and some forty-three hundred refugees. This sea lift originally had been designed to assist the X Corps' concentration at Hungnam, but the intervening order to evacuate Hungnam changed the destination for most of the South Koreans to Pusan. On 10 and 11 December the convoy from Songjin anchored at Hungnam only long enough to unload the Capital Division's headquarters and artillery for employment in the perimeter and to take aboard an advance party of the ROK I Corps headquarters before proceeding to its new destination.48

On the 11th, as the South Koreans from Songjin as well as the Marine and Army troops from the Changjin Reservoir came into Hungnam, the perimeter around the port was comprised of a series of battalion and regimental strongpoints astride the likely avenues of enemy approach some twelve to fifteen miles outside the city. The 3d Division still held the large sector assigned to it when General Almond first shaped the perimeter, from positions below Yonp'o airfield southwest of Hungnam to defenses astride the Changjin Reservoir road at Oro-ri northwest of the port. Battalions of the 7th Division stood in breadth and depth athwart the Pu'on Reservoir road north of Hungnam, and three regiments of the ROK I Corps guarded approaches near and at the coast northeast of the port.49

Although Almond had begun to pull these units into defenses around Hungnam at the beginning of December, enemy forces as of the 11th had not yet made any significant attempt to establish contact with the perimeter units. But Almond expected his beachhead defenses would be tested by enemy units approaching Hungnam along the coast from the northeast, from the Wonsan area to the south, and especially from the direction of the Changjin Reservoir.50

The likelihood that enemy forces pushing to the coast to reoccupy Wonsan would block the routes south of Hungnam had prompted Almond to discard any thought of an overland withdrawal to southern Korea. (Nor had MacArthur ordered such a move.) Almond also considered the roads inadequate to permit the timely movement of large forces. His warning order, issued 9 December, alerted his forces for a "withdrawal by water and air without delay from Hungnam area to Pusan-Pohang-dong area."51 The larger exodus was to be by sea, with the Hungnam defenses contracting as corps forces were outloaded, but airlift was to be employed for as long as the airfield at Yonp'o remained within the shrinking perimeter.52

Evacuation Planning

In deciding how to evacuate his forces and still successfully defend his perimeter, Almond considered two alternatives. He could place all divisions on the perimeter and then withdraw portions of each simultaneously, or he could pull out one division at a time and spread his remaining forces to cover the vacated sector on a shorter front. Since some units were more battle worn than others, especially the 1st Marine Division, he elected the latter method and intended to ship the marines first. They were to be followed by the 7th Division, then the 3d Division.53

Almond planned to phase out the ROK I Corps, corps support units, bulk supplies, and heavy equipment simultaneously with the American Army divisions. This was to be done carefully enough to keep a proper balance between combat and support troops and to insure adequate logistical support. To maintain this balance yet guarantee that the evacuation proceeded as rapidly as possible, he established three points of control. From X Corps headquarters, his G3 and G4 together guided the dispatch of units to the beach. To supervise the actual loading of troops and materiel at water's edge, he organized a control group under Col. Edward H. Forney, a Marine officer serving as Almond's deputy chief of staff. Under Colonel Forney's direction, the 2d Engineer Special Brigade was to operate dock facilities, a reinforced Marine shore party company was to operate the LST and small craft beaches and control the lighterage for ships to be loaded in the harbor anchorages, and some five thousand Korean civilians were to work as stevedores. On the Navy's end of the outloading procedure, Admiral Doyle, through a control unit aboard his flagship Mount McKinley, was to coordinate all shipments, assign anchorages, and issue docking and sailing instructions. Direct liaison was established between Almond's control group ashore and Doyle's control group at sea to match outgoing troops, supplies, and equipment with available ships. Almond also dispatched a control group under Lt. Col. Arthur M. Murray from corps headquarters to Pusan to receive troops, supplies, and equipment arriving by sea and air and to move them as rapidly as possible to assembly areas.54

Including the troops and materiel outloaded at Wonsan and Songjin, Almond needed shipping space for 105,000 troops, 18,422 vehicles, and some 350,000 tons of bulk cargo. Although Admiral Doyle commanded a transport group of over 125 ships, some would have to make more than one trip to meet Almond's needs. The Far East Air Forces' Combat Cargo Command flying out of Yonp'o airfield was to fulfill airlift requirements.55

Tactical air support during the evacuation would be a Navy and Marine responsibility, the Fifth Air Force fighters previously located in northeastern Korea having flown out to Pusan on 3 December. The 1st Marine Air Wing, based at Yonp'o and aboard escort carriers, was to devote its full effort to supporting the corps operation. In addition, Admiral Doyle was to arrange both naval air and naval gunfire support. Reinforced by ships supplied by Admiral Struble, the Seventh Fleet commander, Doyle eventually was able to employ seven carriers in throwing a canopy of aircraft over the corps area and to deploy one battleship, two cruisers, seven destroyers, and three rocket ships in a maneuver area reaching ten miles north and ten miles south of Hungnam to answer Almond's requests for gunfire support.56

To begin an orderly contraction of defenses as the X Corps' strength ashore diminished, the units on the perimeter were to withdraw deliberately as the 1st Marine Division embarked toward the first of three phase lines that Almond drew around Hungnam. In the southwest this first line rested generally along the Yowi-ch'on River, just below Yonp'o airfield, and elsewhere traced an arc about three miles from the heart of Hungnam. (Map 14) The second line differed from the first only in the southwest in the 3d Division sector where it followed the upper bank of the Songch'on River close by Hungnam. The 3d Division's withdrawal to this second line, which would mean the abandonment of Yonp'o airfield, was scheduled to take place as the 7th Division began its embarkation. The third and final line was a tight arc about a mile outside the limits of Hungnam to be occupied by the 3d Division as that division itself prepared to outload. During this final phase of the evacuation General Soule's units were to use rearguard tactics to cover their own embarkation.57

Troops Outloading At Hungnam

General Almond published his formal evacuation order on 11 December, the date on which General MacArthur visited Korea and flew into Yonp'o airfield for a conference with the X Corps commander. After briefing MacArthur on corps dispositions and the plan of evacuation, Almond predicted that the evacuation would be orderly, that no supplies or equipment would be destroyed or abandoned, and that enemy forces would not interfere seriously. The redeployment of the X Corps to southern Korea, he estimated, would be complete by 27 December.58

The Outloading

The 1st Marine Division, as it came into Hungnam from the Changjin Reservoir on 11 December, assembled between the port and Yonp'o airfield. The division outloaded over the following three days and sailed for Pusan at midmorning on the 15th. General Almond the day before had designated Masan, thirty miles west of Pusan, as the division's assembly area. Following the voyage to Pusan and a motor march to Masan, the marines passed to Eighth Army control on 18 December.59

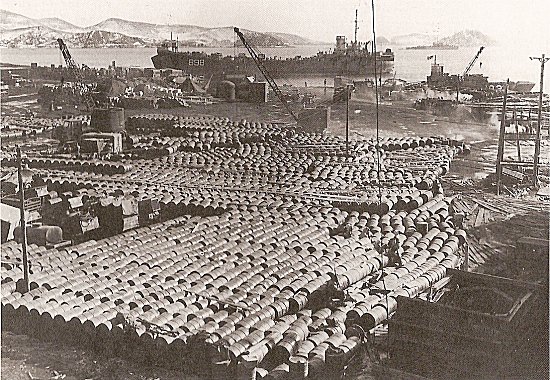

Barrels Of Aviation Fuel To Be Loaded On Ships At Hungnam

Some bulk cargo was shipped out during the Marine outloading, but the heavier evacuation of materiel began after the marines sailed. From 15 December forward, service units gradually moved depots and supply points into the port area proper, and the bulk supplies and heavy equipment were either loaded aboard ships double-banked at the docks or lightered to ships in the harbor. To save time, ammunition was loaded at the docks instead of well out into open water according to usual precautionary practice. This constant outward flow of materiel paralleled unit embarkations through the final day of the evacuation.60

While the marines outloaded by sea, the bulk of the 1st Korean Marine Corps Regiment, which had been attached to the 3d Division, moved to Yonp'o for evacuation by air. General Soule had planned to compensate for the loss of the South Korean marines by pulling his division to the shorter first phase line on 16 December. But several sharp attacks against his positions between Chigyong and Oro-ri during the morning of the 15th prompted him to make his withdrawal that afternoons.61

By the 16th the attacks against the 3d Division on the western and northwestern arcs of the perimeter, enemy patrol contact with the ROK I Corps in the northeast, and other ground and air reports indicated that enemy forces f were closing in around the X Corps perimeter but not in great strength. Parts of the Chinese 81st Division, 27th Army, appeared to have made the attacks on the 3d Division, and a North Korean brigade apparently was moving toward Hungnam over the coastal road from the northeast. A greater immediate problem than the approach of relatively few enemy forces was a mass movement of civilians toward the corps perimeter. Although General Almond had planned to evacuate government officials, their families, and as many others as shipping space allowed, he had not anticipated that thousands of civilians would try to reach Hungnam.62

Besides hampering evacuation operations by overcrowding the port area, the large refugee movement posed a danger of enemy infiltration. According to corps intelligence sources, the enemy was circulating a rumor in Hamhung that the X Corps would provide transporation for all civilians who wished to leave North Korea. The intention was to create a mass move to cover the infiltration of enemy agents and saboteurs. To prevent overcrowding and infiltration, military police, intelligence agents, and perimeter troops attempted to block civilian entry, particularly over the HamhungHungnam road, which carried the larger number of refugees. They were only partially successful. Those civilians already in Hungnam and those who managed to reach the city were screened, then moved to the southeastern suburb of Sohojin, where corps civil affairs personnel distributed food and organized them for evacuation as shipping space became available.63

On the heels of the Marine division, the 7th Division began to outload on 14 December, embarking first the worn troops of the 31st Infantry, 1st Battalion of the 32d Infantry, and 57th Field Artillery Battalion, who had been with the marines in the reservoir area. Most of the division's service units went aboard ship on the 15th and 16th. The 17th Infantry and remainder of the 32d Infantry meanwhile relieved the ROK I Corps on the perimeter and withdrew to the first phase line. Hence, the corps perimeter on the 16th was divided into two nearly equal parts by the Songch'on River, the 7th Division in position above it, the 3d Division holding the sector below. Patrols and outposts deepened the defense as far out as the lower edge of Hamhung.64

After being relieved by the 7th Division, the ROK I Corps outloaded and sailed at noon on 17 December. Although original plans called for the South Koreans to go to Pusan, General MacArthur, apparently as a result of his 11 December visit to Korea, had directed that the corps units then on the Hungnam perimeter be sea lifted to Samch'ok. These units and those being carried to Pusan from Songjin were to pass to Eighth Army control upon debarkation. This transfer would permit General Walker to deploy the South Korean corps immediately, and the landing at Samch'ok would put much of it close at hand for deployment at the eastern end of line B. The landing, actually made at a small port just north of Samch'ok, was completed on 20 December.65

The ROK I Corps' departure on the 17th coincided with the evacuation of most X Corps headquarters sections and troops. Their final destination was Kyongju, fifty miles north of Pusan, where they were to establish an advance corps command post. On the same day, operations at Yonp'o airfield closed as the left flank units of the 3d Division prepared to withdraw to the lower bank of the Songch'on River behind the field the next day. The Marine squadrons that had used the field already had withdrawn to Pusan and Itami, Japan. Last to leave was a Fifth Air Force base unit that had serviced the Marine fighters and General Tunner's cargo aircraft. By the closing date Tunner's planes had lifted out 3,600 troops, 196 vehicles, 1,300 tons of cargo, and several hundred refugees.66

The 18 December withdrawal of General Soule's left flank units to the lower bank of the Songch'on River was a preliminary move in the 3d Division's relief of the two 7th Division regiments still on the perimeter. Soule's forces stepped behind the Songch'on to the second corps phase line on the 19th and on the 19th and 20th spread out to relieve the 17th and 32d Regiments. General Almond closed his command post in Hungnam on the 20th and reopened it aboard Admiral Doyle's Mount McKinley in the harbor, leaving General Soule in command of ground troops ashore.67

Enemy probing attacks, which had slackened noticeably after the 3d and 7th Divisions withdrew to the first corps phase line, picked up again on the 18th and became still more intense on the following day. Three Chinese divisions, the 79th, 80th, and 81st, all from the 27th Army, were believed to be in the nearby ground west of Hungnam, although only the 79th was currently in contact. North and northeast of Hungnam, a North Korean brigade and the reconstituted North Korean 3d Division had been contacted, as had another North Korean force, presumably a regiment.68

None of the enemy strikes on the perimeter did more than penetrate some outposts, and counterattacks rapidly eliminated these gains. So far, all action appeared to be only an attempt to reconnoiter the perimeter. Several explanations for the enemy's failure to make a larger effort were plausible. The bulk of the Chinese in the Changjin Reservoir area apparently were taking time-probably forced to take time-to recuperate from losses suffered in the cold weather and recent battles. All enemy forces undoubtedly were aware that the X Corps was evacuating Hungnam and that they would be able to enter the city soon without having to fight their way in. The contraction of the corps perimeter probably forced the enemy to repeat his reconnaissance. Artillery fire, naval gunfire, and ample close air support may well have prevented the enemy from concentrating sufficient strength for strong attacks. Whatever the reasons, enemy forces had not yet launched a large-scale assault.69

Although an additional unit, a regiment of the North Korean 1st Division, was identified near the northeastern anchor of the corps perimeter on 20 December, enemy attacks diminished on the 20th and 21st as the last troops of the 7th Division embarked and sailed for Pusan. General Barr's troops completed their redeployment on the 27th and moved into an assembly around Yongch'on, west of the new X Corps headquarters at Kyongju.70

New but still small attacks harassed the 3d Division on the 22d as General Soule's 7th, 65th, and 15th Regiments from west to east stood at the second corps phase line to cover the outloading of the last corps artillery units and the first of the division's service units. On the 23d, when Soule pulled his regiments to the last corps phase line in preparation for the final withdrawal from Hungnam, only a small amount of mortar and artillery fire struck the perimeter troops. Whatever conditions so far had kept the Chinese and North Koreans from opening a large assault obtained even after the X Corps' perimeter strength dwindled to a single division.71

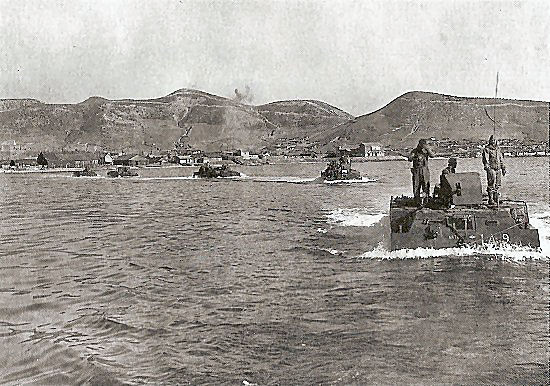

The indirect fire received on the 23d proved to be the last opposition offered. By morning of the 24th the perimeter was silent and remained so as the last of the 3d Division's service units outloaded and as General Soule started his rearguard action to take out his regiments and artillery. A battalion from each regiment stayed on the perimeter while the remaining infantry and the artillery outloaded and while the division's 10th Engineer Combat Battalion and Navy underwater demolition teams prepared port facilities for destruction. At the same time, the last corps supplies, the port operating units, and as many of the remaining refugees as possible were put aboard ship. After General Almond made a final inspection ashore, seven platoons established strongpoints near the beaches to protect the embarkation of the remainder of the covering battalions and the bulk of the 10th Engineer Combat Battalion. In the final steps, Admiral Doyle's warships laid down a wide barrage about a mile and a half inland as the last platoons of the covering force outloaded and as the 10th Engineer Combat Battalion and Navy demolition teams blew up the port before leaving the beaches aboard LVTs and LCMs shortly after 1430.72

Rearguard Troops of 3rd Infantry Division leave Hungnam Beach - 24 December 1950

By Christmas Eve the ships carrying the last X Corps troops and supplies were well out of Hungnam harbor en route to Pusan and to Ulsan, a small port thirty miles north of Pusan. They left behind no serviceable equipment or usable supplies. About 200 tons of ammunition, a like amount of frozen dynamite, 500 thousand-pound aerial bombs, and about 200 drums of oil and gasoline had not been taken out, but "all of this [had] added to the loudness of the final blowup of the part of Hungnam."73 A remarkable number of refugees, over 86,000, had been lifted out of Hungnam since the 11th. Including those evacuated from Wonsan and Songjin, the total number of civilians taken out of northeastern Korea reached 98,100. About the same number had been left behind for lack of shipping space.74

In retrospect, the evacuation of the X Corps from Hungnam had proved most spectacular as a logistical exercise. While the move could be considered a withdrawal from a hostile shore, neither Chinese nor North Korean forces had made any serious attempts to disrupt the operation or even to test the shrinking perimeter that protected the outloading. Logistical rather than tactical matters therefore had governed the rate of the evacuation. Indeed, the X Corps' redeployment south had been a matter of how rapidly Admiral Doyle's ships could be loaded.75

Final Demolitions At Hungnam - USS Begor, APD 127

In announcing the completion of the X Corps' withdrawal from Hungnam in a communique on 26 December, General MacArthur took occasion to appraise UNC operations from the time his command had resumed its advance on 24 November and, once again, to remark on the restrictions that had been placed on him. He blamed the incorrect assessment of Chinese strength, movements, and intentions before the resumption on the failure of "political intelligence . . . to penetrate the iron curtain" and on the limitations placed on field intelligence activities, in particular his not being allowed to conduct aerial reconnaissance beyond the boarders of Korea. So handicapped, his advance, which he later termed a "reconnaissance-in-force," was the "proper, indeed the sole, expedient," and "was the final test of Chinese intentions." In both the advance and the redeployment south, he concluded, "no command ever fought more gallantly or efficiently under unparalleled conditions of restraint and handicap, and no command could have acquitted itself to better advantage under prescribed missions and delimitations involving unprecedented risk and jeopardy.76

But while MacArthur earlier had proclaimed that only by advancing could he determine enemy strength, he had not designed or designated the UNC attack as a reconnaissance in force. Nor was it such. It was, rather, a general offensive whose objective was the northern border of Korea. On the other hand, except that the operations of his command really had nothing to do with "conditions of restraint and handicap," MacArthur was correct in his assessment of the quality of UNC operations. Indeed, in both advance and withdrawl his forces had conducted operations in far largest part with efficiency and with many demonstrations of gallantry.

Notes

1 Eighth Army Comd Rpt, Nar, Dec 50; Eighth Army G3 SS Rpt, Dec 50.

2 Ibid.; Eighth Army PIR 142, 1 Dec 50; Sawyer, KMAG in Peace and War, p. 146; Appleman, South to the Naktong, pp. 618, 667.

3 Eighth Army Comd Rpt, Nar, Dec 50; Eighth Army G3 SS Rpt, Dec 50.

4 Ibid.; Eighth Army PIR 142, 1 Dec 50; Eighth Army PIR 143, 2 Dec 50.

5 For example, British historian David Rees, in Korea: The Limited War (New York: St. Martin's Press, 1964), on page 171 entitled a section covering the Eighth Army's withdrawal "The Big Bug-Out" and on page 176 stated, "At the Front throughout December the moral collapse of the Eighth Army was complete, as bug-out fever raged everywhere."

6 General Almond officially remained the chief of staff.

7 Interv, Appleman with Hickey, 10 Oct 51; Eighth Army G3 SS Rpt, Dec 50; Rad, GX 30141 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CG I Corps et al., 2 Dec 50.

8 Ibid.; Eighth Army Comd Rpt, Nar, Dec 50.

9 Eighth Army Comd Rpt, Nar, Dec 50; Eighth Army G1 SS Rpt, Dec 50; Eighth Army G3 SS Rpt, Dec 50; "Turkish U.N. Brigade Advisory Group, 20 Nov-13 Dec 50"; Rad, GX 30139 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CG 2d Div, 2 Dec 50; Rad, GX 30142 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CG IX Corps et al., 2 Dec 50.

10 Eighth Army G3 SS Rpt, Dec 50; Rad, GX 30146 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CG I Corps et al., 2 Dec 50.

11 Eighth Army PIRs 143, 2 Dec 50, and 144, 3 Dec 50; Rad, CG 30162 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CG I Corps et al., 3 Dec 50.

12 Rad, GX 30162 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CG I Corps et al., 3 Dec 50.

13 Eighth Army G4 SS Rpt, Dec 50; Eighth Army, "Logistical Problems and Their Solutions."

14 Eighth Army Comd Rpt, Nar, Dec 50; Eighth Army G3 SS Rpt, Dec 50; Eighth Army, "Logistical Problems and Their Solutions."

15 Eighth Army G3 SS Rpt, Dec 50; Eighth Army G4 SS Rpt, Dec 50; Eighth Army, "Logistical Problems and Their Solutions"; Field, United States Naval Operations, Korea, pp. 272-74.

16 Eighth Army G4 SS Rpt, Dec 50; Mono, Eighth Army, "Activities of the 3d Transportation Military Railway Service-The Withdrawal From Pyongyang," cp in CMH.

17 Eighth Army Comd Rpt, Nar, Dec 50; Eighth Army G3 SS Rpt, Dec 50.

18 Rad, GX 29613 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CG I Corps and CG IX Corps, 5 Dec 50; Rad, GX 29660 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CG IX Corps, 5 Dec 50; Eighth Army G3 in], 6 and 7 Dec 50.

19 Eighth Army Comd Rpt, Nar, Dec 50; Eighth Army G3 Jnl, 5 Dec 50; Eighth Army G2 SS Rpt, Dec 50; Eighth Army G2 Brief, 6 Dec 50; Eighth Army PIR 147, 6 Dec 50; Rad, GX 29685 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CG I Corps et al., 6 Dec 50; Rad, GX 29706 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to C/S ROKA et al., 6 Dec 50.

20 Eighth Army G3 in], 5 and 6 Dec 50.

21 Rads, GX 29621 KGOO and GX 29661 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CINCFE, 5 Dec 50; Briefing for CG, in Eighth Army G3 Jnl, 6 Dec 50; Rad, CTF 95 to CTG 95.7, 070206 Dec 50; Rad GX 29684 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to C/S ROKA, 6 Dec 50; Rad, GX 29685 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CG I Corps et al., 6 Dec 50; Rad, GX 29706 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to C/S ROKA et al., 6 Dec 50; Rad, GX 29733 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CG IX Corps et al., 7 Dec 50; Rad, GX 29794 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CG I Corps et al., 8 Dec 50.

22 Rad, C 69953, CINCFE to JCS, 28 Nov 50; Rad, JCS 97592, JCS to CINCFE, 29 Nov 50; Rad, C 50095, CINCUNC to DA for JCS, 30 Nov 50; Rad, C 50105, CINCFE to DA, 30 Nov 50.

23 Rad, JCS 97772, JCS to CINCFE, I Dec 50; Rad, C 50332, CINCUNC to DA for JCS, 3 Dec 50.

24 Chief of Staff, FEC, Memo for Gen Collins, 4 Dec 50; Rad, JCS 97917, JCS to CINCFE, 4 Dec 50.

25 Schnabel, Policy and Direction, p. 283; Ltr, Lt Gen Edward M. Almond (Ret) to Col C. H. Schilling, 21 May 1965, copy in CMH.

26 Memo, FEC G3 for FEC C/S, 6 Dec 50.

27 Field, United States Naval Operations, Korea, p. 288; Rad, CX 50635, CINCFE to CG Eighth Army et al., 7 Dec 50; Rad, CX 50801 (CINCUNC Opn O No. 5), CINCUNC to CG Eighth Army et al., 8 Dec 50. The JCS formally approved MacArthur's plan on 9 Dec 50 per Rad, JCS 98400, DEPTAR (JCS) to CINCFE, 9 Dec 50.

28 Truman, Years of Trial and Hope, p. 383.

29 MacArthur Hearings, p. 3536.

30 Ibid.

31 Rad, CX 50635, CINCFE to CG Eighth Army et al., 7 Dec 50; Rad, CX 50801 (CINCUNC Opn O no. 5), CINCUNC to CG Eighth Army et al., 8 Dec 50; Rad, GX 29794 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CG I Corps et al., 8 Dec 50.

32 Rad, GX 29857 KGOP, CG Eighth Army to CG 2d Log Comd and C/S ROKA, 9 Dec 50; Ltr, CG Eighth Army to CG 2d Log Comd, 11 Dec 50, sub: Construction of the Naktong River Defense Line and Completion of Construction of the Davidson and Raider Lines; Eighth Army Comd Rpt, Nar, Dec 50.

33 Rad, GX 35046 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CG I Corps et al., 12 Dec 50.

34 Eighth Army Comd Rpt, Nar, Dec 50; Eighth Army G3 SS Rpt, Dec 50; Rads, GX 29874 KGOO and GX 35071 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CG I Corps et al., 9 Dec and 13 Dec 50, respectively.

35 Eighth Army Comd Rpt, Nar, Dec 50; Eighth Army G3 SS Rpt, Dec 50.

36 Ibid.; Rad, AG IN BSF-1305, CTF 90 to CG Eighth Army et al., 20 Dec 50.

37 Eighth Army Comd Rpt, Nar, Dec 50; Rad, GX 35176 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CG IX Corps and CG 1st Cav Div, 15 Dec 50.

38 Eighth Army Comd Rpt, Nar, Dec 50; Rad, GX 35255 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CG I Corps et al., 18 Dec 50; Rad, GX 35300 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CG 2d Div, 20 Dec 50; Eighth Army G3 Jnl, 20 Dec 50.

39 Rad, CX 51694, CINCFE to CG Eighth Army, 20 Dec 50; Rad, GX 35321 KCG, CG Eighth Army to CINCFE, 21 Dec 50.

40 Eighth Army G3 SS Rpt, Dec 50; Eighth Army PIRs 149-156, 815 Dec 50; Rad, GX 35266 KGI, CG Eighth Army to CINCFE, 18 Dec 50; Eighth Army PIRs 163, 22 Dec 50, and 164, 23 Dec 50.

41 Eighth Army G2 SS Rpt, Dec 50; Eighth Army PIRs 148-164, 823 Dec 50.

42 Bomber Command meanwhile halted its attacks on the Yalu bridges and devoted its main effort to the interdiction of rail lines.

43 Futrell, The United States Air Force in Korea, pp. 243-45. The FEAF estimate of enemy troops killed in December was 39,694.

44 Eighth Army G2 SS Rpt, Dec 50; Eighth Army PIRs 148-164, 823 Dec 50.

45 Ibid.

46 Rad, GX 35226 KGOP, CG Eighth Army to CG X Corps, 17 Dec 50; Rad, CX 35321 KCG, CG Eighth Army to CINCFE, 21 Dec 50; Eighth Army PIRs 160, 19 Dec 50, and 163, 22 Dec 50.

47 Rad, CX 50635, CINCFE to CG Eighth Army et al., 7 Dec 50; Rad, CX 50801 (CINCUNC Opn O No. 5), CINCUNC to CG Eighth Army et al., 8 Dec 50; Cagle and Manson, The Sea War in Korea, pp. 183-84; Field, United States Naval Operations, Korea, pp. 286-88.

48 X Corps Comd Rpt, Sum, Dec 50; X Corps POR 74, 9 Dec 50; X Corps G3 Jul, Entry J-31, 9 Dec 50; X Corps G3 Jul, Entry J-28, 11 Dec 50; Field, United States Naval Operations, Korea, pp. 286, 288-89.

49 X Corps POR 75, 11 Dec 50.

50 X Corps PIRs 74-76, 9-11 Dec50; X Corps Comd Rpt, Sum, Dec 50.

51 X Corps OI 27, 9 Dec 50.

52 X Corps Comd Rpt, Sum, Dec 50.

53 Ibid.; X Corps Opn O 10, 11 Dec 50; X Corps POR 76, 11 Dec 50.

54 X Corps Comd Rpt, Sum, Dec 50; Field, United States Naval Operations, Korea, pp. 289-90.

55 X Corps Comd Rpt, Sum, Dec 50; Field, United States Naval Operations, Korea, p. 289; Cagle and Manson, The Sea War in Korea, pp. 512-14; Futrell, The United States Air Force in Korea, pp. 241-42.

56 Cagle and Manson, The Sea War in Korea, pp. 181-82, 186-87; Futrell, The United States Air Force in Korea, pp. 24819.

57 X Corps Comd Rpt, Sum, Dec 50; X Corps Opn O 10, 11 Dec 50.

58 Ibid.; X Corps Comd Rpt, 11 Dec 50; Memo, Gen Almond, 11 Dec 50, sub: Movement of X Corps to the Pusan Area; Ltr, Gen Almond to CINCUNC, 11 Dec 50, sub: Redeployment of X Corps in Pusan-Pohangdong Area.

59 X Corps Comd Rpt, Sum, Dec 50; X Corps 0130, 14 Dec 50; Montross and Canzona, The Chosin Reservoir Campaign, pp. 338-41, 345; X Corps POR 83, 18 Dec 50.

60 X Corps Comd Rpt, Sum, Dec 50.

61 X Corps PORs 79, 14 Dec 50, and 80, 15 Dec 50; Dolcater, 3d Infantry Division in Korea, pp. 97-100.

62 X Corps PIRs 77-80,12-15 Dec 50; X Corps Comd Rpt, Sum, Dec 50.

63 X Corps Comd Rpt, Sum, Dec 50; X Corps PIRs 77, 12 Dec 50, and 78, 13 Dec 50.

64 X Corps PORs 79-81, 14-16 Dec 50; X Corps OI 31, 16 Dec 50.

65 X Corps Comd Rpt, Sum, Dec 50; Rad, CX 51019, CINCFE to CG Eighth Army et al., 11 Dec 50; Rad, CX 51102, CINCFE to DEPTAR, 12 Dec 50; X Corps PORs 8083, 15-18 Dec 50; Field, United States Naval Operations, Korea, p. 295; Rad, AG IN BSF-1305, CTF 90 to CG Eighth Army et al., 20 Dec 50.

66 X Corps POR 79, 14 Dec 50; X Corps Comd Rpt, 18 Dec 50; X Corps 01 36, 18 Dec 50; Futrell, The United States Air Force in Korea, pp. 241, 248-49; X Corps Comd Rpt, Sum, Dec 50; Cagle and Manson, The Sea War in Korea, p. 191.

67 X Corps Comd Rpt, Sum, Dec 50; X Corps PORs 83-85, 18-20 Dec 50; Dolcater, 3d Infantry Division in Korea, p. 102.

68 X Corps PIRs 81-85, 16-20 Dec 50.

69 Ibid.

70 X Corps Comd Rpt, Sum, Dec 50; X Corps PIRs 85, 20 Dec 50, and 86, 21 Dec 50; X Corps PORs 85, 20 Dec 50, and 86, 21 Dec 50.

71 X Corps Comd Rpt, Sum, Dec 50; X Corps PORs 87, 22 Dec 50, and 88, 23 Dec 50; X Corps PIRs 87, 22 Dec 50, and 88, 23 Dec 50; Dolcater, 3d Infantry Division in Korea, p. 102.

72 X Corps Comd Rpt, Sum, Dec 50; X Corps PIR 89, 24 Dec 50; X Corps POR 89, 24 Dec 50; Dolcater, 3d Infantry Division in Korea, p. 102.

73 Col Edward H. Forney, Special After Action Report, Deputy Chief of Staff, X Corps, 19 Aug-Dec 50, p. 14.

74 X Corps Comd Rpt, Sum, Dec 50; Field, United States Naval Operations, Korea, p. 304.

75 X Corps, Special Report on Hungnam Evacuation, 9-24 Dec 50.

76 Quoted in MacArthur Hearings, pp. 3536-539.

Causes of the Korean Tragedy ... Failure of Leadership, Intelligence and Preparation