Battle for Seoul

General Milburn intended to make no stubborn or prolonged defense of line Delta. He considered it only a phase line to be occupied briefly in the I Corps' withdrawal to line Golden. He planned to mark out additional phase lines between Delta and Golden so that in each step of the withdrawal displacing artillery units would remain within range of the line being vacated and could provide continuous support to infantry units as they withdrew. Each move to the rear was to be made in daylight so that any enemy forces following the withdrawal could be hit most effectively with artillery fire and air strikes.1

Milburn ordered the next withdrawal at midmorning on the 26th after attacks opened during the night by the North Korean I Corps and XIX Army Group made inroads along the western portion of his Delta front. (See Map 32.) Hardest hit were the 11th Regiment of the ROK 1st Division astride Route I and the 65th Infantry at the left of the 3d Division. Chinese also entered a five-mile gap between the ROK 1st and 3d Divisions but made no immediate attempt to move deep. The next position to be occupied by Milburn's forces lay two to five miles below line Delta, generally on a line centered on and slightly above Uijongbu.2

General Hoge ordered conforming adjustments of the IX Corps line. The ROK 6th Division was to withdraw and tie in with the new right flank of the I Corps. Eastward, the British 28th Brigade was to reoccupy the hill masses previously held by the Canadians and Australians above Kap'yong; the 1st Marine Division was to pull back from line Kansas to positions straddling the Pukhan, running through the northern outskirts of Ch'unch'on, and following the lower bank of the Soyang River. Since the marines' withdrawal otherwise would leave the X Corps with an open left flank, General Almond was obliged to order the 2d and 7th Divisions away from the Hwach'on Reservoir and the west shoulder of the North Korean salient in the Inje area. The new line to be occupied by Almond's forces looped northeast from a junction with the 1st Marine Division along the Soyang to a point two miles below Yanggu, then fell off to the southeast to the existing position of the ROK 5th Division below Inje.3

Although the I Corps withdrawal, and thus the chain reaction eastward, was prompted by the heavy enemy pressure in the corps' western sector, there was evidence by 26 April that the main effort of the enemy offensive was beginning to falter. Enemy killed by infantry and artillery fire and air strikes on the I Corps front were estimated to number almost forty-eight thousand approximately the strength of five divisions. Intelligence information indicated that the stand of the Gloster battalion against forces of the 63d Army and the early fumbling of the 64th Army had upset the attack schedule of the XIX Army Group and that the group commander was committing the 65th Army in an attempt to save the situation. But in this and other commitments of reserves, according to prisoner of war interrogations, enemy commanders were confused and their orders vague.4

With only the west sector of the army front under any serious threat, and that beginning to show signs of lessening, General Van Fleet on the 26th established an additional transpeninsular defense line that in the central and eastern sectors lay well north of line Nevada, the final line set out in the 12 April withdrawal plan. The new line incorporated the fortifications of line Golden arching above the outskirts of Seoul. Eastward, it bulged across the Pukhan River five miles above its confluence with the Han, then turned steeply northeast, crossing Route 29 ten miles below Ch'unch'on and cutting Route 24 fifteen miles south of Inje. Continuing to angle northeast, the line touched the east coast just above Yangyang. Implicit in Van Fleet's insistence on thorough coordination between corps during the withdrawal to the new line was that its occupation would be governed by the movement of the I Corps against the continuing enemy pressure on its front. Van Fleet's assignment of corps sectors along the line made the IX Corps responsible for defending the Pukhan and Han corridors; consequently, the 24th Division, currently located directly above that area, was to pass to IX Corps control on the 27th. When, contrary to custom, Van Fleet gave the line no name, it became known as No Name line.5

Of concern to Van Fleet after the I Corps pulled back from the Imjin was the possibility that enemy forces would cross the Han River estuary unseen west of Munsan-ni and sweep down the Kimpo peninsula behind Seoul, overrunning Inch'on, Kimpo Airfield, and the Seoul airport in the process. On 25 April he had asked the commander of the west coast group of Task Force 95 to keep the possible crossing site under surveillance, and on the 26th planes from the group's carriers began to fly over the area while in transit to and from close support targets. The cruiser Toledo meanwhile steamed for the Inch'on area from the Sea of Japan to provide gunfire support.6

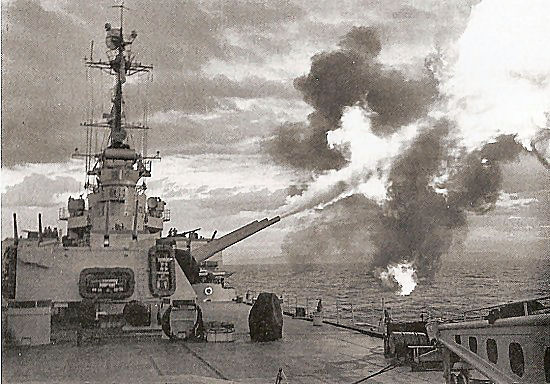

The USS Toledo In Action

Enemy forces reaching the I Corps phase line after dark on the 26th attacked in each division sector except that of the 24th on the corps right. On the front of the 25th Division, Chinese concentrated an assault between two companies of the 27th Infantry, some reaching as far as a mile behind the line before regimental reserves contained them. A radar-directed bomb strike brought down at the point of penetration and ground fire delivered under light provided by a flare ship eliminated the enemy force.7

In a repetition of the pattern of enemy attacks on the I Corps' Delta front the previous night, the hardest assaults struck the ROK 1st Division and 65th Infantry at the left of the 3d Division's position west of Uijongbu. Telling artillery fire and air strikes helped contain penetrations of the 65th'' line and force the Chinese to withdraw. Chinese attacking the 15th Regiment at the right of the ROK 1st Division's line forced a twomile withdrawal before the South Koreans were able to block the advance. North Koreans attacking down Route 1 against the 11th Regiment and against the tank destroyer battalion west of the road broke through the lines of both units and took a particularly high toll of tank destroyer troops before South Korean counterattacks supported by American tanks stopped the advance.8

At 0600 on the 27th, the 24th Division passed to IX Corps control, as had been directed by General Van Fleet, and what had been the boundary between the 24th and 25th Divisions became the new corps boundary. Shortly afterward, General Milburn ordered his remaining forces to withdraw to the next phase line, which would be the last occupied by the I Corps before it moved onto line Golden. West to east, the phase line lay one to seven miles above Golden, touching the Han near the village of Haengju located almost due north of Kimpo airfield below the river, cutting Route 1 and a minor road from the north near the village of Kup'abal-li, crossing Route 3 four miles south of Uijongbu, and also intersecting a minor road along the new corps boundary that below the phase line and line Golden joined Route 2 reaching Seoul from the east. Following suit, General Hoge ordered back the left of the IX Corps. The 24th Division, to which Hoge attached the ROK 6th Division and British 28th Brigade, was to take position adjoining the new I Corps line and stretching along the lower bank of the Pukhan toward the Ch'unch'onSoyang River position of the 1st Marine Division.9

On the I Corps right, the two line regiments of the 25th Division had some difficulty in getting off the first phase line. The 27th Infantry ran into enemy groups that had got behind the regiment during the night, and Chinese closely following the 35th Infantry took that regiment under assault when it set up a covering position to help the 27th Infantry disengage. It was well into the afternoon before the two regiments could break away. General Bradley deployed the same two regiments on the second phase line. In preparation for further withdrawal, Bradley set the Turkish brigade in a covering position midway between the phase line and line Golden and assembled the 24th Infantry behind the Golden fortifications.10

On the 26th General Milburn had reinforced the 3d Division with the 7th Cavalry. In preparation for the withdrawal on the 27th, General Soule deployed the cavalry regiment at the left rear of the division as a precautionwhich proved fortuitousagainst a flanking attack by XIX Army Group forces who were continuing to press hard against the adjacent 15th Regiment of the ROK 1st Division. The cavalrymen fended off a Chinese attack from the northeast that lasted into the afternoon. Along the second phase line, General Soule meanwhile deployed his 7th and 15th Regiments at center and right and assembled the 65th Infantry in reserve. He later set the 7th Cavalry on line at the left.11

The continuing pressure kept the ROK 1st Division pinned in position until late afternoon, then diminished enough to allow the South Koreans to begin the difficult task of disengaging while under attack. Enemy forces, however, failed to follow the withdrawal. Along the second phase line, General Kang deployed the 11th, 15th, and 12th Regiments west to east and set out screening forces well to the front.12

Enemy forces did not regain contact during the night. General Milburn nevertheless expected an eventual followup in strength and ordered his forces to occupy line Golden on the 28th. Again in chain reaction, Milburn's withdrawal order set in motion the move to No Name line by forces to the east.13

From the outset of the enemy offensive General Van Fleet had believed that a strong effort should be made to retain possession of Seoul, not only to gain the tactical advantage in maintaining a foothold above the Han River but also to prevent psychological damage to the Korean people. To give up the ROK capital a third time, he believed, "would ruin the spirit of the nation."14 His determination to fight for the city lay behind his refusal to allow the Eighth Army simply to surrender ground in deep withdrawals and behind his order of 23 April directing a strong stand on line Kansas. Defeated in the latter effort, mainly by the failures of the ROK 6th Division, he had laid out No Name line in the belief that a successful defense of its segment athwart the Pukhan corridor would improve his chances of holding Seoul and that the corridor area could be used as a springboard to recapture the capital if the forces defending the city itself were pushed out.15 In the central and eastern sectors, where enemy attacks had clearly lost their momentum by 26 April, the occupation of No Name would obviate relinquishing territory voluntarily, a cession that would occur if the forces in those sectors moved back to line Nevada as prescribed in the 12 April withdrawal plan.

Convinced by the morning of the 28th that the main enemy effort in the west was wearing out, Van Fleet informed corps commanders that he intended to "hold firmly" on No Name line. They were to conduct an active defense of the line, making full use of artillery in conjunction with armored counterattacks. Though members of his staff considered it a tactical mistake to risk having forces trapped against the north bank of the Han, Van Fleet insisted that there would be no withdrawal from the line unless extreme enemy pressure clearly imperiled Eighth Army positions, and then only if he himself ordered it.16

In case Van Fleet had to call a withdrawal from No Name line, the Eighth Army was to retire to line Waco, a move which would still hold the bulk of the army well above line Nevada. In the west, the new line designated by Van Fleet followed the Nevada trace along the lower bank of the Han; in the central and eastern areas, it lay nine to eighteen miles below No Name line. "For planning purposes only," Van Fleet issued instructions for occupying line Waco late on the 28th.17

As I Corps forces began their withdrawal to line Golden at midmorning on the 28th, North Koreans in regimental strength were sighted massing near Haengju, the Han River village above Kimpo airfield, apparently in preparation for crossing the river. The massed fire of two artillery battalions and 8inch fire from the cruiser Toledo, now stationed just off Inch'on, inflicted heavy casualties on the enemy group and forced the survivors to withdraw. A Chinese battalion attacking the 7th Cavalry below Uijongbu early in the morning but soon breaking contact after failing to penetrate and patrols investigating the positions of the 25th Division around noon were the only other enemy actions along the corps front during the day.18

The ROK 1st Division, which had scarcely more than a mile to withdraw, reached line Golden early in the day. Assigned a narrow sector from the Han to a point just short of Route 1, General Kang was able to hold his 12th Regiment and tank destroyer battalion in reserve. The 11th and 15th Regiments manning the Golden fortifications were able to use a battalion each in outpost lines, organizing these units about two miles to the northwest. Behind the 3d Division, the 1st Cavalry Division occupied Golden positions between and including Routes 1 and 3. General Milburn ordered General Soule to return the 7th Cavalry to the 1st Cavalry Division, to assemble the 3d Division less the 65th Infantry in Seoul in corps reserve, and to prepare counterattack plans. Milburn attached the 65th Infantry to the 25th Division so that General Bradley, using the 65th and his own reserve, the 24th Infantry, could man the eastern sector of the Golden line while the remainder of his division was withdrawing.19

As deployed for the defense of Seoul by evening of the 28th, the I Corps had six regiments on line and the same number assembled in and on the edges of the city. Below the Han to meet any enemy attempt to envelop Seoul were the British 29th Brigade at the base of the Kimpo peninsula in the west and the Turkish brigade on the east flank. With adequate reserves, fortified defenses, and a narrower front that allowed heavier concentrations of artillery fire, the corps was in a position far stronger than any it had occupied since the beginning of the enemy offensive.20

In contrast, there was further evidence that the enemy's offensive strength was weakening. The most recent prisoners taken had only one day's rations or none at all. Interrogation of these captives revealed that local foraging produced very little food and that resupply had collapsed under the Far East Air Forces' interdiction of enemy rear areas. The steady air attacks also had seriously impeded the forward movement of artillery. Confusion and disorganization among enemy forces appeared to be increasing. Commanders were issuing only such general instructions as "go to Seoul" and "go as far to the south as possible." On one occasion, according to prisoners, reserve forces ordered forward moved south under the impression that Seoul already had fallen. One factor in the deterioration was a high casualty rate among political officers- especially at company level- on whom the Chinese Army depended so heavily for maintaining troop motivation and discipline.21

Obviously willing, if growing less able, to continue the attack on Seoul, the North Korean 8th Division assisted on its left by Chinese in what appeared to be regimental strength struck the outpost line of the ROK 1st Division shortly before midnight on the 28th. Accurate defensive fire, especially from tanks, artillery, and the guns of the Toledo, broke up the attack before enemy assault forces could get through the outpost line and reach the main South Korean positions. Tank-infantry forces sent out by General Kang after daylight followed and fired on retreating enemy groups for two miles, observing between nine hundred and a thousand enemy dead along the route.22

The 8th Division's attack proved to be the only serious enemy attempt to break through the Golden fortifications. Another effort appeared to be in the offing during the day of the 29th when patrols and air observers reported a large enemy buildup on the front of the 25th Division, but heavy artillery fire and air attacks delivered after dark broke up the enemy force.23 Division patrols searching the enemy concentration area after daylight on the 30th found an estimated one thousand enemy dead. Across the corps front, patrols moving as much as six miles above line Golden on the 30th made only minor contacts. On the basis of the patrol findings, General Milburn reported to General Van Fleet that the enemy forces on his front were staying out of artillery range while regrouping and resupplying for further attacks.24 Actually in progress was the beginning of a general enemy withdrawal.

In dropping back to No Name line, Eighth Army forces since 22 April had given up about thirty-five miles of territory in the I and IX Corps sectors and about twenty miles in the sectors of the X and ROK III Corps. Logistical planning completed in anticipation of the enemy offensive had kept line units well furnished with all classes of supplies during the attacks and at the same time had prevented any loss of stocks stored in major supply points during the withdrawal. Gearing removal operations to the phased rearward movements, service forces had shifted supplies and equipment southward to predetermined locations from which line units could be readily resupplied without risking the loss of supply points to advancing enemy forces.25

Steady rail movements and back loading aboard ships had all but cleared Inch'on of supplies by the 30th, and LSTs were standing by to take aboard the 2d Engineer Special Brigade and ten thousand South Koreans who had been operating the port.26 Against the possibility that Inch'on would have to be given up, General Ridgway on the 30th took steps to forestall a repetition of the heavy damage done to the port when it was abandoned in January, damage that had served only to hinder use of the port after it was recaptured. Ridgway instructed General Van Fleet not to demolish port facilities if it became necessary to evacuate Inch'on again but to leave it to UNC naval forces to prevent the enemy from using the port.27

Among U.S. Army divisions, casualties suffered between 22 and 29 April totaled 314 killed and 1,600 wounded. In both number and rate, these losses were scarcely more than half the casualties suffered among the divisions engaged for a comparable period of time during the Chinese offensive opened in late November.28

Among a variety of estimates, an Eighth Army headquarters report for the eight-day period from evening of the 22d to evening of the 30th listed 13,349 known enemy dead, 23,829 estimated enemy dead, and 246 taken captive. This report included information obtained daily from U.S. and allied ground units only. At UNC headquarters in Tokyo, the estimate was that enemy forces suffered between 75,000 and 80,000 killed and wounded, 50,000 of these in the Seoul sector. Other estimates listed 71,712 enemy casualties on the I Corps front and 8,009 in the IX Corps sector. Although none of the estimates was certifiable, enemy losses were unquestionably huge.29

Notwithstanding the high enemy losses, General Van Fleet cautioned on 1 May that the enemy had the men to attack again "as hard as before or harder."30 The total strength of Chinese forces in Korea as of that date was believed to be about 542,000 and that of North Korean forces to be over 197,000. The 1 May estimate in General Ridgway's headquarters credited the enemy with having 300,000 men currently in position to attack, most of these on the central front.

Notes

1 I Corps Rpt, The Communist First Phase Spring Offensive, Apr 51, p. 28.

2 Ibid., pp. 28-33; Rad, CIACT 4-15, CG I Corps to CG 3d Div et al., 26 Apr 51; Rad, CICCG 4-19, CG I Corps to CG Eighth Army, 26 Apr 51; Dolcater, 3d Infantry Division in Korea, pp. 203-04.

3 Rad, IXACT-1355, CG IX Corps to CG 1st Marine Div, 26 Apr 51; Rad IXACT-1356, CG IX Corps to CGs 28th Brit Brig and ROK 6th Div, 26 Apr 51; X Corps 01 163, 26 Apr 51.

4 I Corps Rpt, The Communist First Phase Spring Offensive, Apr 51, p. 38; Hq, USAFFE, Intel Dig, no. 96, 16-28 Feb 53, p. 27.

5 Rad, GX-4-5200 KGOP, CG Eighth Army to CG I Corps et al., 26 Apr 51; Rad, GX-4-5341 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CGs I and IX Corps, 26 Apr 51.

6 Rad, GX-4-5130 KNLO, CG Eighth Army to CTG 95.1, 25 Apr 51; Rad, CTE 95.11 to CTG 95.1, 26 Apr 51; Rad, AG In no. CX4480, CTG 95.1 to CG Eighth Army, 26 Apr 51; Field, United States Naval Operations, Korea, p. 346.

7 I Corps Rpt, The Communist First Phase Spring Offensive, Apr 51, pp. 29-30.

8 Ibid., pp. 32, 34.

9 Rad, GX-4-5341 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to CGs I and IX Corps, 26 Apr 51; I Corps Rpt, The Communist First Phase Spring Offensive, Apr 51, p. 29; Rad, CIACT 4-172, CG I Corps to CG 3d Div et al., 27 Apr 51; Rad, IXACT1366, CG IX Corps to CG 24th Div et al., 27 Apr 51.

10 I Corps Rpt, The Communist First Phase Spring Offensive, Apr 51, p. 30.

11 Ibid., p. 32; Rad, CIACT 4-167, CG I Corps to CGs 1st Cav Div and 3d Div, 26 Apr 51.

12 I Corps Rpt, The Communist First Phase Spring Offensive, Apr 51, p. 34.

13 Rad, CICCG 4-22, CG I Corps to CG Eighth Army, 28 Apr 51; Rad, CIACT 4-179, CG I Corps to CG 1st Cav Div et al., 28 Apr 51.

14 Quotation from USAWC Research Paper, "A Will to Win," based on Intervs, Col Bruce F. Williams with Van Fleet, 6 Apr 73, p. 26.

15 Interv, Appleman with Van Fleet, 15 Sep 51.

16 Ibid.; Rad, GX-4-5638 KGOO, CG Eighth Army to C/S ROKA et al., 28 Apr 51.

17 Rad, GX-4-5749 KGOP, CG Eighth Army to CG I Corps et al., 28 Apr 51.

18 I Corps Rpt, The Communist First Phase Spring Offensive, Apr 51, pp. 30-34; Rad, CIACT 4-179, CG I Corps to CG 1st Cav Div et al., 28 Apr 51; Rad, AG In no. CX-5246, COMNAVFE to CINCFE, 29 Apr 51.

19 I Corps Rpt, The Communist First Phase Spring Offensive, Apr 51, pp. 30, 33-34; Dolcater, 3d Infantry Division in Korea, pp. 204, 206.

20 I Corps Rpt, The Communist First Phase Spring Offensive, Apr 51, p. 35 and Map 7, following p. 38.

21 Ibid., pp. 35, 38; George, The Chinese Communist Arm in Action, p. 10.

22 Rad, CICCG 4-23, CG I Corps to CG Eighth Army, 29 Apr 51; Rad, AG In no. CX 5260, CTF 95 to COMNAVFE et al., 29 Apr 51; I Corps Rpt, The Communist First Phase Spring Offensive, Apr 51, p. 36.

23 A number of published works on the war report that six thousand enemy attempted to ferry the Han and attack down the Kimpo peninsula to outflank Seoul on 29 April and that air attacks defeated the effort. The official records do not support these accounts. The authors may have been referring to the North Korean effort to cross the river at Haengju on the 28th.

24 I Corps Rpt, The Communist First Phase Spring Offensive, Apr 51, pp. 36-37; Rad, CICCG 4-24, CG I Corps to CG Eighth Army, 30 Apr 51.

25 Eighth Army, "Logistical Problems and Their Solutions," pp. 105-06.

26 Also jamming Inch'on in hopes of being evacuated by sea were some two hundred thousand refugees. Most of these had come from Seoul during the past week, leaving only about a hundred thousand inhabitants in the capital city.

27 Eighth Army, "Logistical Problems and Their Solutions," p. 107; Eighth Army Comd Rpt, Nar, Apr 51; Rad, CX 61384, CINCFE to CG Eighth Army, 30 Apr 51.

28 Reister, Battle Casualties and Medical Statistics, p. 30.

29 Eighth Army G3 PORs, 22-30 Apr 51; Facts on File, vol. XI, no. 548, 27 Apr-3May 51, p. 137; I Corps Rpt, The Communist First Phase Spring Offensive, Apr 51, p. 38; IX Corps Comd Rpt, Nar, Apr 51.

30 Facts on File, vol. XI, no. 548, 27 Apr-3 May 51, p. 137.

Causes of the Korean Tragedy ... Failure of Leadership, Intelligence and Preparation