The Foundation of Freedom is the Courage of Ordinary People History  On Line On Line

BK Comment: I have been somewhat critical of previous brochures in this Army series but can only admire and recommend this one, which ably handles the task of dealing with the lost, tragic years of trying to bring an end to this vicious war by diplomatic means under the most difficult of circumstances.

Introduction The Korean War was the first major armed clash between Free World and Communist forces, as the so-called Cold War turned hot. The half-century that now separates us from that conflict, however, has dimmed our collective memory. Many Korean War veterans have considered themselves forgotten, their place in history sandwiched between the sheer size of World War II and the fierce controversies of the Vietnam War. The recently built Korean War Veterans Memorial on the National Mall and the upcoming fiftieth anniversary commemorative events should now provide well-deserved recognition. I hope that this series of brochures on the campaigns of the Korean War will have a similar effect. The Korean War still has much to teach us: about military preparedness, about global strategy, about combined operations in a military alliance facing blatant aggression, and about the courage and perseverance of the individual soldier. The modern world still lives with the consequences of a divided Korea and with a militarily strong, economically weak, and unpredictable North Korea. The Korean War was waged on land, on sea, and in the air over and near the Korean peninsula. It lasted three years, the first of which was a seesaw struggle for control of the peninsula, followed by two years of positional warfare as a backdrop to extended cease-fire negotiations. The following essay is one of five accessible and readable studies designed to enhance understanding of the U.S. Army's role and achievements in the Korean conflict.

Years of Stalemate July 1951-July 1953 The first twelve months of the Korean War (June 1950-June 1951) had been characterized by dramatic changes in the battlefront as the opposing armies swept up and down the length of the Korean peninsula. This war of movement virtually ended on 10 July 1951, when representatives from the warring parties met in a restaurant in Kaesong to negotiate an end to the war. Although the two principal parties to the conflict-the governments of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea) and the Republic of Korea (ROK or South Korea)-were more than willing to fight to the death, their chief patrons-the People's Republic of China and the Soviet Union on the one hand and the United States and the United Nations (UN) on the other-were not. Twelve months of bloody fighting had convinced Mao Tse-tung, Joseph V. Stalin, and Harry S. Truman that it was no longer in their respective national interests to try and win a total victory in Korea. The costs in terms of men and materiel were too great, as were the risks that the conflict might escalate into a wider, global conflagration. Consequently, they compelled their respective Korean allies to accept truce talks as the price for their continued military, economic, and diplomatic support. For the soldiers at the front and the people back home, the commencement of negotiations raised hopes that the war would soon be over, but such was not to be. While desirous of peace, neither side was willing to sacrifice core principles or objectives to obtain it. The task of finding common ground was further complicated by the Communists' philosophy of regarding negotiations as war by other means. This tactic significantly impeded the negotiations. And while the negotiators engaged in verbal combat around the conference table, the soldiers in the field continued to fight and die-for two more long and tortuous years.  Strategic Setting The advent of truce talks in July 1951 came on the heels of a successful United Nations offensive that had not only cleared most of South Korea of Communist forces but captured limited areas of North Korea as well. By 10 July the front lines ran obliquely across the Korean peninsula from the northeast to the southwest. In the east, UN lines anchored on the Sea of Japan about midway between the North Korean towns of Kosong and Kansong. From there the front fell south to the "Punchbowl," a large circular valley rimmed by jagged mountains, before heading west across the razor-backed Taebaek Mountains to the "Iron Triangle," a strategic communications hub around the towns of P'yonggang, Kumhwa, and Ch'orwon. From there the front dropped south once again through the Imjin River Valley until it reached the Yellow Sea at a point roughly twenty miles north of Seoul. Manning this line were over 554,000 UN soldiers-approximately 253,000 Americans (including the 1st Marine, 1st Cavalry, and 2d, 3d, 7th, 24th, and 25th Infantry Divisions), 273,000 South Koreans, and 28,000 men drawn from eighteen countries-Australia, Belgium, Canada, Colombia, Ethiopia, France, Great Britain, Greece, India, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, the Philippines, Sweden, Thailand, Turkey, and the Union of South Africa. Facing them were over 459,000 Communist troops, more than half of whom were soldiers of the Chinese People's Liberation Army (PLA). Since the political leaders of the two warring coalitions had signaled their willingness to halt the fighting, the generals on both sides proved reluctant to engage in any major new undertakings. For the most part the commander of UN forces, General Matthew B. Ridgway, and his principal subordinate, General James A. Van Fleet, Eighth Army commander, confined their activities to strengthening UN positions and conducting limited probes of enemy lines. Their Communist counterparts adopted a similar policy. Consequently, the two sides exchanged artillery fire, conducted raids and patrols, and occasionally attempted to seize a mountain peak here or there, but for the most part the battle lines remained relatively static. So too, unfortunately, did the positions of the truce negotiators, who were unable to make any progress on the peace front during the summer. The chief stumbling block was the inability of the parties to agree on a cease-fire line. The Communists argued for a return to the status quo ante- that is, that the two armies withdraw their forces to the prewar boundary line along the 38th Parallel. This was not an unreasonable position, since the combat lines were not all that far from the 38th Parallel. The UN, however, refused to agree to a restoration of the old border on the grounds that it was indefensible in many places. Current UN positions were much more defensible, and a more defensible border was clearly advantageous, not only in protecting South Korea in the present conflict, but in discouraging future Communist aggression. Consequently, UN negotiators argued in favor of adopting the current line of contact as the cease-fire line. A deadlock immediately ensued, with the Communists employing every conceivable artifice to undermine the UN position. They argued over every point, large and small, procedural as well as substantive, in an effort to wear down the UN negotiators. They hurled insults and engaged in hours of empty posturing. They released scurrilous propaganda, staged provocative incidents, and exploited any misstep or accident on the part of the UN to their full advantage, all in an effort to embarrass, discredit, and entrap the UN negotiators. While more restrained in their behavior, the American-led negotiating team refused to be intimidated by Communist negotiating tactics. When the two sides finally tired of trading accusations, they would sit and stare at each other over the conference table in absolute silence for hours on end. Finally, on 23 August the Communists broke off the negotiations.

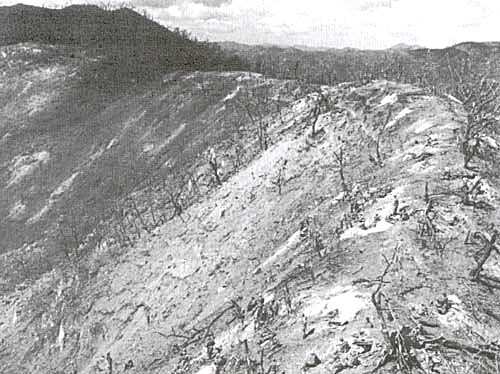

Click For Full Size Color MapOperations The UN Summer/Fall Offensive, July-November 1951 If the Chinese and North Koreans had hoped to intimidate the United Nations into making concessions, they were very much mistaken. Rather than rewarding Communist misbehavior by beseeching the enemy to return to the bargaining table, the United Nations Command decided to chastise him by launching a limited offensive in the late summer and early fall of 1951. Militarily, the offensive was justified on the grounds that it would allow UN forces to shorten and straighten sections of their lines, acquire better defensive terrain, and deny the enemy key vantage points from which he could observe and target UN positions. But the offensive also had a political point to make-that the United Nations would not be stampeded into accepting Communist proposals. Much of the heaviest fighting revolved around the Punchbowl, which served as an important Communist staging area. The United Nations first initiated limited operations to seize the high ground surrounding the Punchbowl in late July. By mid-August the battle had begun to intensify around three interconnected hills southwest of the Punchbowl that would soon be known collectively as Bloody Ridge. Three days after the Communists walked out of the Kaesong talks, the ROK 7th Division captured Bloody Ridge after a week of heavy combat. It was a short-lived triumph, for the following day the North Koreans recaptured the mountain in a fierce counterattack. Determined to wrest the heavily fortified bastion from the Communists, Van Fleet ordered the U.S. 2d Infantry Division's 9th Infantry to scale the ridge. The battle raged for ten days, as the North Koreans repulsed one assault after another by the increasingly exhausted and depleted 9th Infantry. Finally, on 5 September the North Koreans abandoned the ridge after UN forces succeeded in outflanking it. Approximately 15,000 North Koreans and 2,800 UN soldiers were killed, wounded, or captured on Bloody Ridge's slopes.

Bloody Ridge

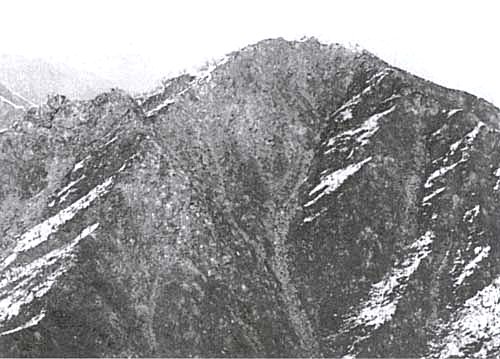

(National Archives) After withdrawing from Bloody Ridge, the North Koreans set up new positions just 1,500 yards away on a seven-mile-long hill mass that was soon to earn the name Heartbreak Ridge. If anything, the enemy's defenses were even more formidable here than on Bloody Ridge. Unfortunately, the 2d Division's acting commander, Brig. Gen. Thomas de Shazo, and his immediate superior, Maj. Gen. Clovis E. Beyers, the X Corps commander, seriously underestimated the strength of the North Korean position. They ordered a lone infantry regiment-the 23d Infantry and its attached French battalion-to make what would prove to be an ill-conceived assault straight up Heartbreak's heavily fortified slopes. The attack began on 13 September and quickly deteriorated into a familiar pattern. First, American aircraft, tanks, and artillery would pummel the ridge for hours on end, turning the already barren hillside into a cratered moonscape. Next, the 23d's infantrymen would clamber up the mountain's rocky slopes, taking out one enemy bunker after another by direct assault. Those who survived to reach the crest arrived exhausted and low on ammunition. Then the inevitable counterattack would come-wave after wave of North Koreans determined to recapture the lost ground at any cost. Many of these counterattacks were conducted at night by fresh troops that the enemy was able to bring up under the shelter of neighboring hills. Battles begun by bomb, bullet, and shell were inevitably finished by grenade, trench knife, and fist as formal military engagements degenerated into desperate hand-to-hand brawls. Sometimes dawn broke to reveal the defenders still holding the mountaintop. Just as often, however, the enemy was able to overwhelm the tired and depleted Americans, tumbling the survivors back down the hill where, after a brief pause to rest, replenish ammunition, and absorb replacements, they would climb back up the ridge to repeat the process all over again. And so the battle progressed-crawling up the hill, stumbling back down it, and crawling up once again-day after day, night after night, for two weeks. Because of the constricting terrain and the narrow confines of the objectives, units were committed piecemeal to the fray, one platoon, company, or battalion at a time. Once a particular element had been so ground up that it could no longer stand the strain, a fresh unit would take its place, and then another and another until the 23d Infantry as a whole was fairly well shattered. Finally, on 27 September the 2d Division's new commander, Maj. Gen. Robert N. Young, called a halt to the "fiasco" on Heartbreak Ridge as American planners reconsidered their strategy. The 23d Infantry's failure to capture Heartbreak Ridge had not come from a lack of valor. It took extreme bravery to advance up Heartbreak's unforgiving slopes under intense enemy fire. And when things did not go right, it took equal courage to take a stand so that others might live. One person who took such a stand was Pfc. Herbert K. Pililaau, a quiet, six-foot-tall Hawaiian. Pililaau's outfit, Company C, 1st Battalion, 23d Infantry, was clinging to a small stretch of Heartbreak's ridge top on the night of 17 September when a battalion of North Koreans came charging out of the darkness from an adjacent hill. The company fought valiantly, but a shortage of ammunition soon compelled it to retreat down the mountain. After receiving reinforcements and a new issue of ammunition, the Americans advanced back up the ridge. North Korean fire broke the first assault, but Company C soon regrouped and advanced again, recapturing the crest by dawn. The pendulum of war soon reversed its course, however, and by midday the men of Company C were once again fighting for their lives as the North Korean battalion surged back up the hill. Running low on ammunition, the company commander called retreat. Pililaau volunteered to remain behind to cover the withdrawal. As his buddies scrambled to safety, Pililaau wielded his Browning automatic rifle with great effect until he too had run out of ammunition. He then started throwing grenades, and when those were exhausted, he pulled out his trench knife and fought on until a group of North Korean soldiers shot and bayoneted him while his comrades looked on helplessly from a sheltered position 200 yards down the slope. Determined to avenge his death, the men of Company C swept back up the mountain. When they recaptured the position, they found over forty dead North Koreans clustered around Pililaau's corpse. Pililaau's sacrifice had saved his comrades, and for that a grateful nation posthumously awarded him the Medal of Honor. Yet his valiant act could not alter the tactical situation on the hill. As long as the North Koreans could continue to reinforce and resupply their garrison on the ridge, it would be nearly impossible for the Americans to take the mountain. After belatedly recognizing this fact, the 2d Division crafted a new plan that called for a full division assault on the valleys and hills adjacent to Heartbreak to cut the ridge off from further reinforcement. Spearheading this new offensive would be the division's 72d Tank Battalion, whose mission was to push up the Mundung-ni Valley west of Heartbreak to destroy enemy supply dumps in the vicinity of the town of Mundung-ni.

Heartbreak Ridge

(National Archives)It was a bold plan, but one that could not be accomplished until a way had been found to get the 72d's M4A3E8 Sherman tanks into the valley. The only existing road was little more than a track that could not bear the weight of the Shermans. Moreover, it was heavily mined and blocked by a six-foot-high rock barrier built by the North Koreans. Using nothing but shovels and explosives, the men of the 2d Division's 2d Engineer Combat Battalion braved enemy fire to clear these obstacles and build an improved roadway. While they worked, the division's three infantry regiments-9th, 38th, and 23d-launched coordinated assaults on Heartbreak Ridge and the adjacent hills. By 10 October everything was ready for the big raid. The sudden onslaught of a battalion of tanks racing up the valley took the enemy by surprise. By coincidence, the thrust came just when the Chinese 204th Division was moving up to relieve the North Koreans on Heartbreak. Caught in the open, the Chinese division suffered heavy casualties from the American tanks. For the next five days the Shermans roared up and down the Mundung-ni Valley, over-running supply dumps, mauling troop concentrations, and destroying approximately 350 bunkers on Heartbreak and in the surrounding hills and valleys. A smaller tank-infantry team scoured the Sat'ae-ri Valley east of the ridge, thereby completing the encirclement and eliminating any hope of reinforcement for the beleaguered North Koreans on Heartbreak.  The armored thrusts turned the tide of the battle, but plenty of hard fighting remained for the infantry before French soldiers captured the last Communist bastion on the ridge on 13 October. After a month of nearly continuous combat, the 2d Division was finally king of the hill. All totaled the division suffered over 3,800 casualties, nearly half of whom came from the 23d Infantry and its attached French battalion. Conversely, the Americans estimated that they had inflicted 25,000 casualties on the enemy in and around Heartbreak Ridge. While the Punchbowl was the scene of some of the hardest fighting during the UN's summer-fall offensive, the United Nations was not idle elsewhere. Along the east coast South Korean troops succeeded in pushing north to the outskirts of Kosong, while in the west five UN divisions (ROK 1st, British 1st Commonwealth, and U.S. 1st Cavalry and 3d and 25th Infantry) advanced approximately four miles along a forty-mile-wide front from Kaesong to Ch'orwon, thereby gaining greater security for the vital Seoul-Ch'orwon railway. By late October UN operations had succeeded in securing most of the commanding ground along the length of the front. The price of these gains had not been cheap-approximately 40,000 UN casualties. Yet the enemy had suffered even more, and the determination demonstrated by the United Nations Command in taking the offensive was probably a key factor in persuading the Communists to return to the bargaining table. Renewed Talks, Diminished Fighting: The Second Korean Winter, November 1951-April 1952 On 25 October UN and Communist negotiators reconvened the truce talks at a new location, a collection of tents in the tiny village of P'anmunjom, six miles east of Kaesong. After some sparring, the Communists dropped their demand for a return to the 38th Parallel and accepted the UN position that the cease-fire line be drawn along the current line of contact. In exchange, the UN bowed to Communist demands that a truce line be agreed upon prior to the resolution of other outstanding issues. To avoid the danger that the Communists might stop negotiating once a line had been established, the Americans insisted that both sides be permitted to continue fighting until all outstanding questions had been resolved. The two sides also agreed that the proposed armistice line would only be valid for thirty days. Should a final truce not be arrived at within that time, then the agreement over the line of demarcation would be invalid. Still, the willingness of the United Nations to accept the current line of contact as the final line of demarcation between the two Koreas represented a significant windfall for the Communists, for it served as a fairly strong indicator that the United Nations had no desire to press deeper into North Korea. The termination of the UN offensive and the resumption of truce talks in late October had a noticeably calming effect on the front. On 12 November Ridgway instructed Van Fleet to assume an "active defense." Thereafter, offensive operations were to be limited to those actions necessary to strengthen UN lines. When the armistice negotiators formally embraced the line of demarcation accords on 27 November, Van Fleet went one step further by prohibiting his subordinates from initiating any offensive operations other than counterattacks to recapture ground lost to an enemy attack. The Communists likewise refrained from undertaking major actions, and the resulting lull gave the United Nations the opportunity to accomplish a major change in battlefield lineup.

Click For Full Size Color MapBetween December 1951 and February 1952 the United States withdrew the 1st Cavalry and 24th Infantry Divisions from Korea and replaced them with two National Guard formations, the 40th and 45th Infantry Divisions. Ridgway had been reluctant to make the swap, fearing that the newly trained divisions would not be as effective as the two veteran units they were replacing. In fact, the UN commander had recommended that the two Guard divisions be kept at their staging areas in Japan as a source of individual replacements for the divisions already in Korea. But Army Chief of Staff General J. Lawton Collins insisted that the National Guard divisions deploy to Korea intact. Not to do so, Collins maintained, would trigger a rancorous public debate over the Guard's role and fuel allegations that the Army did not trust its own mobilization training system. Fortunately the changeover went smoothly, and soon the two new divisions-which largely consisted of draftees led by a cadre of National Guardsmen-were performing just as well as the Regular units they had replaced, units that by this time in the war likewise contained large numbers of replacements and draftees.

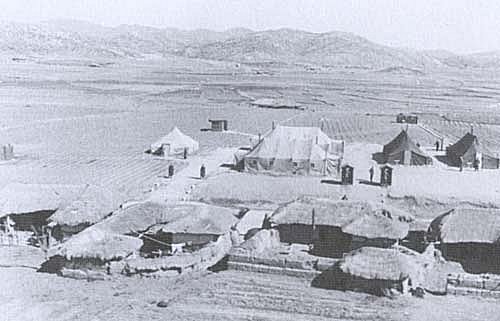

P'anmunjom truce tents

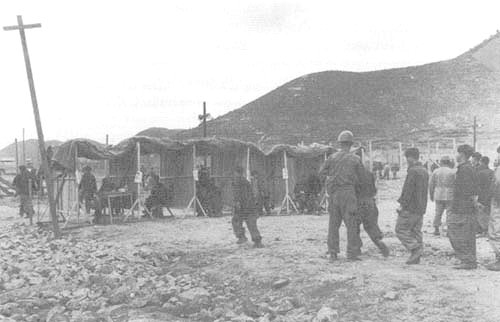

(National Archives) While the Army realigned its order of battle, the P'anmunjom negotiators struggled to finalize the truce agreement in time to meet the thirty-day deadline. When they failed in this, they agreed to extend the deadline by an additional two weeks, but this deadline also came and went without noticeable progress. By this point, however, winter had fully set in, making a renewal of major operations problematic at best. Raids and patrols continued, if for no other reason than to prevent inaction from dulling the troops' combat edge, but overall the level of combat was minimal. The decline in activity was accompanied by a precipitous drop in UN casualties, from about 20,000 during the month of October to under 3,000 per month between December 1951 and April 1952. All in all, the commanders on both sides seemed content to sit out the winter and let the negotiators do the heavy fighting. And fight they did. Although a number of issues separated UN and Communist negotiators, the chief stumbling block to the arrangement of a final armistice during the winter of 1951-1952 revolved around the exchange of prisoners. At first glance, there appeared to be nothing to argue about, since the Geneva Conventions of 1949, by which both sides had pledged to abide, called for the immediate and complete exchange of all prisoners upon the conclusion of hostilities. This seemingly straightforward principle, however, disturbed many Americans. To begin with, UN prisoner-of-war (POW) camps held over 40,000 South Koreans, many of whom had been impressed into Communist service and who had no desire to be sent north upon the conclusion of the war. Moreover, a considerable number of North Korean and Chinese prisoners had also expressed a desire not to return to their homelands. This was particularly true of the Chinese POWs, some of whom were anti-Communists whom the Communists had forcibly inducted into their army. Many Americans recoiled at the notion of returning such men into the hands of their oppressors, and for several months American policymakers wrestled with the POW question.

Winter in Korea

(National Archives)Acquiescing to a total exchange of prisoners as called for by the Geneva Conventions would quickly settle the issue and pave the way for a final agreement ending the hostilities. On the other hand, the desire of enemy soldiers not to return to their homelands was clearly a useful propaganda weapon for the West in the wider Cold War. Establishing the right of prisoners to chose their own destinies might also pay significant dividends in any future war with the Communists, as many enemy soldiers might desert or surrender if they knew that they would not be forced to return to their Communist-controlled homelands afterward. But no one suffered any delusion about how the Communists would react to the voluntary repatriation concept. The newly established governments of North Korea and the People's Republic of China were extremely sensitive to anything that even remotely challenged their legitimacy. This was especially true of the Communist Chinese government in Peking, which would undoubtedly recoil at the suggestion that some of its former soldiers be turned over to its mortal enemy, the rival Chinese Nationalist government on Taiwan. Clearly then, any attempt to assert voluntary repatriation would complicate the truce negotiations and prolong the war. Ultimately, it was the moral aspect of the question which decided President Harry S. Truman. In the name of allied amity, President Truman had dutifully repatriated Soviet citizens who had fallen into American hands after World War II. Much to his dismay, the Soviet government had mistreated, imprisoned, or even killed many of the returnees. Truman had no desire to repeat this heart-wrenching experience if he could avoid it. In a war that was being fought in the name of national self-determination and human liberty, he found it unconscionable to forcibly return people to totalitarian societies. Consequently, after much soul searching, Truman made voluntary repatriation a central tenet of America's negotiating position in February 1952. Truman's decision met with cries of anger from the Communists, who accused the United States of violating the Geneva accords, despite the fact that they themselves routinely violated that treaty's most basic precepts regarding the treatment of prisoners. Undaunted, the United Nations proceeded to lay the groundwork for allowing anti-Communist prisoners to avoid involuntary repatriation. To begin with, it reclassified the more than 40,000 South Koreans being held in UN compounds as "civilian internees" rather than prisoners of war, a categorization that would allow them to be eventually released in the South. Next, the United Nations began to screen all of its prisoners to identify those who wished to return to their homelands after the war and those who did not. The screening process aggravated tensions inside the POW camps, which were already the site of frequent altercations between pro- and anti-Communist prisoners. Guided by Communist agents who had deliberately allowed themselves to be captured in order to infiltrate the camps, pro-Communist prisoners staged a series of increasingly violent uprisings during the spring of 1952, much to the embarrassment of UN officials. Nevertheless, the screenings continued, and in April 1952 UN officials revealed the results-only 70,000 of the 170,000 civil and military prisoners then held by the United Nations wished to return to North Korea and the People's Republic of China.

Repatriation screening of Communist POWs. 1952

(National Archives) The results of the initial survey stunned Communist and UN officials alike. While the Communists were willing to accept the reclassification of South Koreans who had served in their ranks as civilian internees, the sheer number of POWs who purportedly wished to avoid repatriation represented an affront that they dared not ignore. The report thus drove the Communists to dig in their heels even further on the repatriation question, and they refused to accept anything short of a complete return of all of their nationals to their control. Conversely, the survey also served to lock the United Nations into its position. Having asserted the principle of voluntary repatriation and demonstrated that a large number of individuals wished to take advantage of it, any retreat would represent a major political and moral defeat for the UN. With neither side willing to compromise, the armistice talks became hopelessly deadlocked over the POW question. To gain additional leverage on this issue, Communist authorities instructed their agents in the POW camps to step up their disruptive activities. Armed with a startling array of homemade weapons, pro-Communist elements deftly employed intimidation and violence to gain control of the interiors of many POW camps. Then, in early May, Communist prisoners scored a stunning coup when they succeeded in capturing Brig. Gen. Francis T. Dodd, the commandant of the UN's main POW camp on Koje-do. To achieve his release, American authorities pledged to suspend additional repatriation screenings in a poorly worded communique that seemed to substantiate Communist allegations that the UN had heretofore been mistreating prisoners. The episode humiliated the United Nations Command and handed Communist negotiators and propagandists alike a new weapon that they wielded with great zeal, both within the negotiating tent and on the larger stage of world public opinion. A Return to War: The Summer/Fall Campaigns, May-November 1952 As positions at the negotiating table hardened, spring thaws offered the prospect for renewed military operations. Neither side, however, showed much enthusiasm for such undertakings. Since the tempo of the war had first begun to ebb after the initiation of truce talks in July 1951, both sides had expended enormous amounts of effort to solidify their frontline positions. The United Nations' main line consisted of a nearly unbroken line of bunkers, trenches, and artillery emplacements that stretched for over one hundred fifty miles from one coast of Korea to the other. Communist defenses were even more impressive. Because of their overall inferiority in firepower, the Chinese and North Koreans had taken extraordinary efforts to harden their positions. They burrowed deep into the sides of mountains, creating intricate warrens of tunnels and caves capable of housing entire battalions of infantry. Communist bunkers were often more solidly built than UN emplacements and were usually impervious to anything but a direct hit by bomb or shell. They were also generally better sited than UN bunkers and better concealed to avoid the prying eyes of hostile aviators, something UN soldiers did not have to worry about. Finally, the Communists built in greater depth than their adversaries, not just below ground, but on top of it, as they typically extended their fortifications up to twenty miles behind their front line. These emplacements were manned by over 900,000 men, approximately 200,000 more soldiers than the United Nations had under arms in Korea. Over the winter the Communists had also more than doubled the number of artillery pieces they had on the front lines, while the static nature of the war had likewise permitted them to improve their overall supply situation, notwithstanding the best efforts of UN aviators to interdict Communist supply lines. Thus, by the spring of 1952 the UN faced a well-trained, battle-hardened, robust opponent who could not be easily defeated. Since both sides had already indicated their willingness to settle the conflict roughly along the current front lines, neither side had any incentive to risk a major offensive against the other. This was especially true for the UN commanders, who unlike their totalitarian adversaries always had to keep public opinion foremost in their minds. Too many friendly casualties could undermine support for the war at home and force the United Nations to acquiesce to Communist demands at the negotiating table. Consequently, General Mark W. Clark, who replaced General Ridgway as overall UN commander in mid-1952, kept UN offensive operations to a minimum to avoid unnecessary losses. The Communists, for whom human casualties were of less consequence, likewise eschewed the big offensive in the belief that they could just as easily erode the UN's will to continue the struggle through the daily grind of trench warfare. Raids, patrols, bombardments, and limited objective attacks thus remained the order of the day, as both sides contented themselves with making light jabs at their adversary rather than attempting to land a knockout blow. The absence of grand offensives and sweeping movements notwithstanding, service at the front was just as dangerous in 1952 as it had been during the more fluid stages of the war. By June Communist guns were hurling over 6,800 shells a day at UN positions. During particularly hotly contested actions, Communist gunners occasionally fired as many as 24,000 rounds a day. UN artillerists repaid the compliment five-, ten-, and sometimes even twenty-fold, and still not a day went by when Communist and UN soldiers did not clash somewhere along the front line. One of the most common missions performed by UN infantrymen was the small raid for the purpose of capturing enemy prisoners for interrogation. These operations were usually launched at night and were extremely dangerous-indeed, relatively few succeeded in capturing any prisoners. At this level, the war was a very personal affair-it was man against man, rifle against grenade, fist against knife. Small-unit fights required a great deal of courage, and sometimes the bravest men were those who did not carry a rifle at all-the medics. One such man was Sgt. David B. Bleak, a medical aidman attached to the 40th Infantry Division's 223d Infantry. On 14 June 1952, Sergeant Bleak volunteered to accompany a patrol that was going out to capture enemy prisoners from a neighboring hill. As the patrol approached its objective the enemy detected it and laid down an intense stream of automatic weapons and small-arms fire. After attending to several soldiers cut down in the initial barrage, Sergeant Bleak resumed advancing up the hill with the rest of the patrol. As he neared the crest, he came under fire from a small group of entrenched enemy soldiers. Without hesitation, he leapt into the trench and charged his assailants, killing two with his bare hands and a third with his trench knife. As he emerged from the emplacement, he saw a concussion grenade fall in front of a comrade and used his body to shield the man from the blast. He then proceeded to administer to the wounded, even after being struck by an enemy bullet. When the order came to pull back, Sergeant Bleak ignored his wound and picked up an incapacitated companion. As he moved down the hill with his heavy burden, two enemy soldiers bore down on him with fixed bayonets. Undaunted, Bleak grabbed his two assailants and smacked their heads together before resuming his way back down the mountain carrying his wounded comrade. Sergeant Bleak's actions were so distinctive that June day that they won him one of the 131 Medals of Honor awarded during the Korean War. Yet a day did not go by in which some American soldier did not risk his life for his comrades on some nameless Korean hillside. This was particularly true for those soldiers assigned to the outpost line-a string of strongpoints several thousand yards to the front of the UN's main battle positions. The typical outpost consisted of a number of bunkers and interconnecting trenches ringed with barbed wire and mines perched precariously on the top of a barren, rocky hill. As the UN's most forward positions, the outposts acted as patrol bases and early warning stations. They also served as fortified outworks that controlled key terrain features overlooking UN lines. As such, they represented the UN's first line of defense and were accorded great importance by UN and Communist commanders alike. Not surprisingly, the outposts were the scenes of some of the most vicious fighting of the war. While most of these actions were on a small scale, some of the biggest battles of 1952 revolved around efforts either to establish, defend, or retake these outposts. Operation Counter provides one example of some of the larger outpost battles. During Counter the 45th Infantry Division sought to establish twelve new outposts on high ground overlooking the division's main battle line outside of Ch'orwon. The division easily seized eleven of its twelve objectives during a night assault on 6 June, with the twelfth falling into American hands six days later during a second-phase attack. But if capturing the new outposts had been relatively easy, holding them would not be. The Chinese reacted violently to the American initiative, and by the end of June the 45th Division had repulsed more than twenty Communist counterattacks on the newly established positions. Still the enemy came, and in mid-July his persistence paid off when Chinese troops succeeded in pushing elements of the 2d Infantry Division off one of these outposts-a key mountain nine miles west of Ch'orwon known as Old Baldy. Two companies from the 23d Infantry recaptured the hill after bitter hand-to-hand fighting on 1 August, but in mid-September the enemy again seized the hill, only to lose it several days later to a determined counterattack made by the 38th Infantry and a platoon of tanks. The savage, seesaw struggle atop Old Baldy was repeated in one way or another on countless mountain peaks and ridges during 1952, as the two sides struggled to gain ascendancy over the rugged no-man's-land that separated their respective battle lines. The heavy casualties incurred in these bitter outpost battles discouraged General Clark from authorizing any new offensives after Operation Counter. This defensive-mindedness rankled General Van Fleet, who believed that the high casualties the United Nations was experiencing were due in part to the UN's allowing the enemy to launch attacks when and where he wished. Van Fleet therefore pressed Clark to authorize additional limited offensives that would allow UN forces to regain the initiative from the enemy and compel him to fight on American terms. One potential candidate for such an operation was Triangle Hill, a mountain three miles north of Kumhwa. The United Nations was suffering heavy casualties in the area on account of the proximity of the opposing battle lines, which in some cases lay only 200 yards apart. Seizing Triangle Hill and its neighbor-Sniper Ridge-would force the enemy to fall back over 1,200 yards to the next viable defensive position, thereby strengthening UN dominance over the sector and reducing friendly casualties. Finally, an offensive would also serve a political purpose. On 8 October UN negotiators had walked out of the armistice talks out of frustration over being unable to reach an accommodation with the enemy on the prisoner issue. With the talks now officially recessed and no hope in sight for a resolution of the conflict, a demonstration of UN resolve seemed in order. Van Fleet was confident that, given sufficient support, two infantry battalions would be able to capture the Triangle Hill complex in just five days with about 200 casualties. Swayed by Van Fleet's arguments, Clark agreed to authorize the attack. On 14 October, 280 artillery pieces and over 200 fighter-bomber sorties began pummeling Triangle Hill. Unfortunately, Communist defenses proved tougher than expected, and reinforcements had to be funneled in-first one battalion, then another, and another. When the smoke finally cleared several weeks later, two UN infantry divisions (the U.S. 7th and the ROK 2d) had suffered over 9,000 casualties in an ultimately futile attempt to capture Triangle Hill. Estimates of Chinese casualties exceeded 19,000 men, but the Communists had the manpower for such fights and did not flinch from flinging men into the breach to hold key terrain. The United Nations did not have such resources.

Soldiers of Battery C, 936th Field Artillery Batt

Below:

Artillery may have dominated the battlefield, but ultimately it was infantry that captured and held ground.

Here, Company F, 9th Infantry, advances in central Korea.

(National Archives)

The Third Korean Winter, December 1952-April 1953 By the time the battles for Triangle Hill and Sniper Ridge had wound down in mid-November, both sides had begun the now familiar pattern of settling down for yet another winter in Korea. As temperatures dropped so too did the pace of combat. Still, shelling, sniping, and raiding remained habitual features of life at the front, as did patrol and guard duty, so that even the quietest of days usually posed some peril. For most frontline soldiers, home was a "hootchie," the name soldiers gave to the log and earth bunkers that were the mainstay of UN defenses in Korea. Built for the most part into the sides of hills, the typical hootchie housed from two to seven men. Each bunker was usually equipped with a single automatic weapon which could be fired at the enemy through above-ground firing ports. Inside, candles and lamps shed their pale light on the straw-matted floors and pinup-bedecked walls of the cramped, five-by-eight-foot areas that comprised a hootchie's living quarters. Oil, charcoal, or wood stoves provided heat, bunk beds made of logs and telephone wire offered respite, and boxes of extra ammunition and hand grenades gave comfort to the men for whom these humble abodes were home. However Spartan, the hootchie provided welcome shelter from the daily storms of bomb, bullet, rain, and snow that raged outside. Keeping up morale is difficult in any combat situation, but when the fighting devolves into a prolonged stalemate, it is particularly hard to maintain. Consequently, the Army developed an extensive system of personnel and unit rotations to combat soldier burnout and fatigue. Rotation began in a modest way at the small-unit level, where many companies established warm-up bunkers just behind the front lines. Every three or four days a soldier could expect a short respite of a few hours' duration back at the warm-up bunker. There he would be able to spend his time as he saw fit, reading, writing letters, washing clothes, or getting a haircut. When operations were not pressing, many companies also arranged to send a dozen or so men at a time somewhat farther to the rear for a 24-hour rest period. The ultimate rest and recuperation (R and R) program, however, was a five-day holiday in Japan that Eighth Army tried to arrange for every soldier on an annual basis. Eighth Army complemented these individual R and R activities with an extensive unit rotation program. Companies regularly rotated their constituent platoons between frontline and reserve duty. Similarly, battalions rotated their companies, regiments rotated their battalions, divisions rotated their regiments, and corps rotated their divisions, all to ensure that combat units periodically had a chance to rest, recoup, retrain, and absorb replacements. Last but not least, the Army maintained a massive individual replacement program in an effort to equalize as much as possible the burdens of military service during a limited war.

A soldier from the 180th Infantry mans a machine gun from inside a bunker;

Below, living quarters inside a "hootchie."

(National Archives)

In September 1951 the Army had introduced a point system that tried to take into account the nature of individual service when determining eligibility for rotation home to the United States. According to this system, a soldier earned four points for every month he served in close combat, two points per month for rear-echelon duty in Korea, and one point for duty elsewhere in the Far East. Later, an additional category-divisional reserve status-was established at a rate of three points per month. The Army initially stated that enlisted men needed to earn forty-three points to be eligible for rotation back to the States, while officers required fifty-five points. In June 1952 the Army reduced these requirements to thirty-six points for enlisted men and thirty-seven points for officers. Earning the required number of points did not guarantee instant rotation; it only meant that the soldier in question was eligible to go home. Nevertheless, most soldiers did return home shortly after they met the requirement. The point system was a marvelous palliative to flagging spirits, as it gave every soldier a definite goal in an otherwise indefinite and seemingly goalless war. Every man knew that typical frontline duty would enable him to return home after about a year of service in Korea. The system also helped boost the spirits of loved ones back home. This was of some consequence in helping to maintain public support for what was an increasingly unpopular war. Yet for all of its psychological and political benefits, the program was not without its costs. The constant turnover generated by the policy-approximately 20,000 to 30,000 men per month-was terribly inefficient from the vantage point of manpower administration and created tremendous strains on the Army's personnel and training systems. The program also hurt military proficiency by increasing personnel turbulence and by producing a continuous drain on skilled manpower. No sooner had a soldier become fully acclimatized to the physical, mental, and technical demands of Korean combat than he was rotated home, only to be replaced by a green recruit who lacked these skills. This was true not only of the enlisted men, who were rushed to the front with little or no field training, but of the officers as well. Indeed, by the fall of 1952 most junior officers with World War II combat experience had been rotated home and replaced by recent Reserve Officers' Training Corps graduates who had neither command nor combat experience. In a sinister twist, the system also reduced the effectiveness of many veteran soldiers, who became progressively more cautious and unreliable in combat as their eligibility for rotation neared. All of this meant that combat proficiency tended to stagnate in American units during the course of the war. This contrasted sharply with those Communist units that had avoided heavy casualties and managed to keep their morale intact. In these units battlefield acumen steadily increased as the war progressed thanks to the Communists' rather Draconian personnel policies. In the Red Army, victory or death were the only ways home. The disparity in combat experience between the typical American and Communist combat unit was just one factor that contributed to the Eighth Army's heavy reliance on air and artillery support. Political sensitivity at home to the war's mounting body count, the stagnant, siege-like nature of the war, and a natural desire on the part of commanders to spare the lives of their men also contributed to the United Nations Command's preference for expending metal rather than blood. The Communists understood the terrible power of America's industrial might and attempted to compensate for it in a variety of ways. They steadily increased the size of their own artillery park until it exceeded that of the UN's, though they never managed to match the technical proficiency and ammunition reserves enjoyed by American artillerists. They dug deep, moved at night, and became masters of the arts of infiltration, deception, and surprise, all to minimize their vulnerability to the awesome destructive power wielded by the UN's air, land, and naval forces. Yet when push came to shove, the Communists also had the political will, the authoritarian control, and the manpower reserves to indulge in human wave attacks. American industrial might could and did obliterate many such attacks, but ultimately it was the infantry who held ground, and, when the Communists wanted a piece of terrain badly enough, they generally had the human wherewithal to take it. The Final Summer, May-July 1953 The year 1953 found 768,000 UN soldiers facing over one million Communist troops along battle lines that had not materially changed for nearly two years. Spring thaws brought the customary increase in military activity, as Communist soldiers emerged from their winter dens to probe UN outposts. But the new year also brought with it some fresh developments on the political and diplomatic fronts-developments that would dramatically alter the annual rites of spring at the battlefront. In January 1953 Dwight D. Eisenhower succeeded Harry S. Truman as President of the United States. Eisenhower's ascension to the presidency created an air of uncertainty among Communist leaders. Though he had campaigned on a platform promising to end the war, some Communists feared that Eisenhower, a former five-star general whose Republican Party contained some rabidly hawkish elements, might seek to end the war by winning it. Communist uncertainty about the future increased in March, when one of North Korea's preeminent patrons, Soviet leader Joseph V. Stalin, died. Stalin's death triggered a succession struggle inside the Soviet Union. Preoccupied with their own political affairs, Kremlin leaders sought to minimize Soviet involvement in potentially destabilizing activities in the outside world. Chief among these was the war in Korea which, should it escalate, might lead to a direct conflict with the United States-a conflict which the inward-looking Soviets desperately wanted to avoid. Consequently, shortly after Stalin's death, Soviet officials began to signal a new interest in seeing the Korean conflict put to rest. These sentiments were echoed by Mao, who likewise found that the conflict in Korea was detracting from his ability to address pressing domestic issues inside the newly formed People's Republic of China. The convergence of these events- the death of Stalin, the ascension of Eisenhower, and the growing desire on the part of all sides to find a way out of a seemingly unending and unprofitable conflict- created an environment conducive to a settlement of the Korean imbroglio. On 26 April UN and Communist negotiators returned to the truce tent at P'anmunjom after a six-month hiatus. This time Communist negotiators expressed a willingness to allow prisoners of war to decide whether or not they wanted to return to their homelands. This key concession opened the door to fruitful negotiations. As a goodwill measure, both sides quickly agreed to an immediate exchange of sick and wounded prisoners. The exchange (dubbed Operation Little Switch) resulted in the repatriation of 684 UN and 6,670 Communist personnel. The two parties then sat down to the laborious task of hammering out all of the many technical details pertaining to the actual implementation of a cease-fire and a final, full exchange of prisoners. Even at this late date, American negotiators found that their Communist counterparts were determined to seek every possible advantage, and the talks dragged on, week after week, month after month. In June South Korean President Syngman Rhee, who opposed any resolution of the conflict that left North Korea in Communist hands, jarred negotiators on both sides when he unilaterally released about 25,000 North Korean prisoners who had previously voiced a desire to remain in South Korea after the war. The release, which Rhee thinly disguised as a prison "breakout," angered American and Communist negotiators alike and temporarily disrupted the negotiations. Yet the act also helped the North Korean government save face, for by allowing many anti-Communist North Koreans to "escape," South Korea spared the North Korean government some of the embarrassment of having to admit that a large number of its captured soldiers did not want to return home. Thus, after some compulsory sputtering, the Communists chose to remain at the negotiating table, and the talks proceeded despite Rhee's attempts at disruption. One might have expected that the Communists' newfound interest in seeking a cessation of hostilities would have translated to inaction on the battlefield, especially as prospects for a final settlement became progressively more imminent. Unfortunately, such was not the case. Rather, the Communists chose to increase the tempo of the war. In part the heightened activity reflected the natural desire of Communist generals to secure the best possible ground before the armistice went into effect. But the Communist offensives of the spring and summer of 1953 also served a broader political purpose. Ever mindful of the wider propaganda aspects of the struggle between East and West, the Communists were determined to end the war on a positive note. A final offensive that seized additional territory would give the Communists the opportunity to portray themselves as victors whose martial prowess had finally compelled the United Nations to sue for peace. Such claims would also allow Communist propagandists to paper over some of the more bitter pills the Communists would have to swallow in the upcoming accords. Communist military activity had begun in early March with company-size probes of various UN frontline positions. By mid-month the Chinese had escalated to battalion-size attacks. After a failed attempt to capture a UN hill outpost nicknamed "Little Gibraltar," the Chinese turned their gaze onto one of the central battlefields of the previous year-Old Baldy. On the evening of 23 March a Chinese battalion supported by mortar and artillery fire overran a Colombian company on Old Baldy. Repeated efforts by the 7th Infantry Division to regain the mountain failed to dislodge the Chinese, who were determined to cling to the pulverized rock regardless of the cost. Although the UN had killed or wounded two to three Chinese for every UN soldier lost on Old Baldy, General Maxwell D. Taylor, who had recently replaced Van Fleet as Eighth Army commander, decided that the mountain was not worth additional UN lives, and on 30 March he suspended UN efforts to retake the hill.

7th Infantry Division trenches, July 1953

(National Archives)April brought a lull in Communist activities, but in May the front began to heat up as company and battalion attacks gave way to regimental-size assaults. Then in June, as the P'anmunjom negotiators sat down to draw up a final cease-fire line, the enemy launched a major, three-division offensive against the ROK II Corps in the vicinity of Kumsong. The Chinese succeeded in pushing the South Koreans back about three miles before the front restabilized, a significant advance after two years of stagnant trench warfare. Elsewhere UN forces largely succeeded in repulsing more limited Communist attacks, and by the end of June the intensity of the fighting had once again subsided. The Communists, however, were by no means done. After consolidating their gains and bringing up additional supplies and reinforcements, the Communists launched what was to be their biggest offensive operation since the spring of 1951.

Click For Full Size Color MapThe offensive began on 6 July. After hammering South Korean lines south of the Iron Triangle, the Chinese turned their attention to Pork Chop Hill, a company-size 7th Division outpost that over the past year had seen about as much fighting as its neighboring peak, Old Baldy. Following a ferocious artillery and mortar barrage, wave after wave of Chinese infantrymen stormed up Pork Chop Hill. Backed by some heavy artillery fire of their own, the beleaguered defenders valiantly held on. Both sides funneled in reinforcements, with the Chinese committing a new battalion for every fresh company the Americans sent in. By 11 July General Taylor reluctantly decided to abandon Pork Chop Hill. As had been the case on Old Baldy, Taylor could not justify risking more lives for a hill that was of minimal strategic significance, especially given the fact that an armistice was just around the corner. Communist commanders operated under a different calculus-one that held potentially unnecessary losses of life to no account. Two days after Taylor withdrew from Pork Chop Hill, six Chinese divisions slammed into UN lines south of Kumsong. The ROK II Corps once again bore the brunt of the assault, falling back in confusion for eight miles before regrouping along the banks of the Kumsong River. UN counterattacks regained some of this lost ground, but there seemed little point in pressing the issue. On 20 July the negotiators reached an armistice agreement which they signed seven days later in a ceremony at P'anmunjom. At 2200 on 27 July 1953, an eery silence fell across the front. The Korean War was over. Analysis The last two months of the war had been some of the most horrific of the entire conflict. In less than sixty days Communist artillery had fired over 800,000 rounds at UN positions, while UN artillery had repaid the favor nearly sevenfold, sending over 4.7 million shells back at their tormentors. Approximately 100,000 Communist and nearly 53,000 UN soldiers were killed, captured, or wounded during those final two months of combat. For their trouble the Communists had gained a few miles of mountainous terrain and some grist for their propaganda mills, but these gains could not mask the speciousness of Communist claims that they had won the war. In truth, the Korean War had been rather inconclusive. Under the leadership of the United States, the United Nations had successfully defended the sovereignty of a free and democratically elected government from totalitarianism while simultaneously demonstrating the ability of the international community to stand up effectively against aggression. On the other hand, UN action had been possible only because the Soviet Union had chosen to walk out of the UN Security Council in 1950, a costly miscalculation that the Soviets were unlikely to repeat in the future. Nor had the UN been able to obtain its optimistic goal of liberating North Korea.

Lt. Gen. William K. Harrison, Jr., U.S. Army and Lt. Gen. Nam Il, North Korean People's Army, sign the armistice agreement on 27 July 1953.

(National Archives)From the Communist viewpoint, the war likewise brought mixed results. Not only had the North Koreans failed to conquer the South, but they had actually suffered a net loss of 1,500 square miles of territory as the price of their aggression. On the other hand, the Communists had successfully rebuffed UN attempts to liberate the North, while the conflict had propelled the young People's Republic of China to a place of prominence on the world stage. Finally, for good or ill, the war had calcified Cold War animosities and fueled a wider geopolitical confrontation between East and West that would dominate world affairs for the next forty years. Thus the Korean conflict would have great repercussions, despite the fact that little territory changed hands as a result of it. Perhaps the greatest repercussions of the Korean conflict, however, were the effects the war had on the human beings it touched-the soldiers it maimed, the civilians it displaced, and the families around the world who lost their sons and brothers, fathers and lovers to bomb, bullet, and shell. For the Korean War was as bloody as it was inconclusive. United Nations forces suffered over 559,000 casualties during the war, including approximately 94,000 dead. America's share of this bill totaled 36,516 dead and 103,284 wounded. The enemy had taken prisoner 7,245 Americans during the war. The UN estimated that Communist military casualties exceeded two million dead, wounded, and prisoners. Civilian losses were even more appalling-approximately one million South Korean and up to two million North Korean civilians either died, disappeared, or were injured during the course of the war, while millions more became refugees. While territorial losses and disproportionate casualties belied Communist claims of victory, no facet of the war exposed the bankruptcy of communism more clearly than the prisoner issue. In accordance with the final armistice agreement, both sides directly exchanged all prisoners who desired to return to their homelands. All told, 75,823 Communist and 12,773 UN personnel (including 3,597 Americans) returned home from captivity under this arrangement (Operation Big Switch). Prisoners who had expressed a desire not to be repatriated were sent to a temporary camp at P'anmunjom. There government representatives were allowed to talk with their respective nationals under the impartial supervision of a five-member Neutral Nations Repatriation Commission. The interviews served to ensure that soldiers had not been coerced into refusing repatriation. They also gave the governments involved the opportunity to try and persuade their nationals to return home. When the interviews were over, each man was free to chose whether or not he wanted to return home. The numbers were revealing. Of the 359 UN personnel sent to the camp, ten decided to come home, two decided to go to neutral third countries, and the remainder-347-decided to live among the Communists. Included among these were twenty-one Americans who chose to remain with their captors. In contrast, 22,604 Communist soldiers initially chose not to be repatriated. After being processed by the Repatriation Commission, 628 relented and returned home. The rest-over 21,000 Chinese and North Koreans-chose to remain in the non-Communist world, with the Koreans going to South Korea and the Chinese to Nationalist-controlled Taiwan. When added to the roughly 25,000 North Koreans Rhee had freed in June, this meant that over 46,000 Communist soldiers had refused repatriation. No better testimony as to the merits of life under communism existed than this. The United States had taken a noble stand in asserting that prisoners had a right not to return to societies they found objectionable, but the price of establishing this principle had been high. After the P'anmunjom negotiators had agreed to use the line of contact as a cease-fire line in November 1951, the repatriation question had been the only substantial issue over which the two sides remained at loggerheads. By insisting on voluntary repatriation-a right that had heretofore not existed in international law-the United States had adopted a course that had prolonged the war by fifteen months, during which 125,000 United Nations and over 250,000 Communist soldiers had become casualties. The 46,000 Chinese and North Koreans who escaped communism as a result of American opposition to forcible repatriation had truly been given a precious, if dearly bought, gift. Yet the nonrepatriates were not the only ones to have benefited from America's willingness to fight for principles in which it believed. In Korea, the real struggle had never been about the control of this hill or that hill. Rather, it had been about the principles of national self-determination and of freedom from oppression. By successfully defending the fledgling Republic of Korea, the American GI, together with his comrades in arms from South Korea and eighteen other nations, had secured the freedom of millions of South Korean civilians from Communist oppression. This was a great achievement, but it was not a job that, once done, could stand by itself. For while the armistice of 27 July 1953 ended the fighting in Korea, it had not truly ended the war. The armistice was just that-a temporary cease-fire-and not a treaty of peace. It reflected the realization by all parties that neither side had either the will or the means to compel the other to bow to its political agenda. Hence the warring parties had agreed to disagree-to stop the shooting and to transfer the war from the battlefield to the diplomatic field. There the conflict has remained, despite sporadic incidents and border clashes, for half a century. The inability of the two sides to resolve their differences has meant that the two Koreas and their allies have had to remain on a war footing along the inter-Korean border ever since. Fifty years after the North Korean invasion, Communist and United Nations soldiers still glare at each other across the demilitarized zone established in July 1953. Together with the South Koreans, U.S. Army troops continue to make up the bulk of the UN contingent in Korea. The burdens of protecting South Korea from the threat of renewed Communist aggression over the past half-century have been great for the United States. Billions of dollars have been spent and some additional lives have been lost, the latter as a result of sporadic Communist violations of the cease-fire. Yet by standing unswervingly behind its commitments, the United States in general-and the millions of men and women of the United States armed forces who have served their country in Korea since 1953 in particular-has guaranteed that the sacrifices made by men like Private Pililaau, Sergeant Bleak, and thousands of other American fighting men during the Korean War were not made in vain.

Further Readings Alexander, Bevin. Korea: The First War We Lost. New York: Hippocrene, 1986. Blair, Clay. The Forgotten War: America in Korea, 1950-53. New York: Doubleday, 1987. Brune, Lester H., ed. The Korean War: Handbook of the Literature and Research. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1996. Edwards, Paul M., comp. The Korean War: An Annotated Bibliography. Westport, Conn.: Greenwood Press, 1998. Fehrenbach, T. R. This Kind of War: A Study in Unpreparedness. New York: Macmillan, 1963. Gugeler, Russell A. Combat Actions in Korea. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1970. Hastings, Max. The Korean War. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1987. Hermes, Walter G. Truce Tent and Fighting Front. United States Army in the Korean War. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1988. Hinshaw, Arned. Heartbreak Ridge: Korea, 1951. New York: Praeger, 1989. Marshall, S. L. A. Pork Chop Hill. New York: Permabooks, 1959. Rees, David. Korea: The Limited War. New York: St. Martin's Press, 1964. Stueck, William. The Korean War: An International History. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1995. Westover, John G. Combat Support in Korea. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Army Center of Military History, 1987. Cover: A 155-mm. howitzer firing at night (National Archives)

Causes of the Korean Tragedy ... Failure of Leadership, Intelligence and Preparation

The Foundations of Freedom are the Courage of Ordinary People and Quality of our Arms

|