The M1911A1 was widely respected for its reliability and lethality. However, its single action/cocked and locked design required the user to be very familiar and well-trained to allow carrying the pistol in the "ready-to-fire" mode. Consequently, M1911A1s were often prescribed to be carried without a round in the chamber. Even with this restriction on the user, numerous unintentional discharges were documented yearly.

The M1911A1 had been the standard handgun issued to Marines for many decades. Selected weapons were modified in the 1980s to meet the requirements of the MEU(SOC) in lieu of arming them with the M9 9mm pistol.

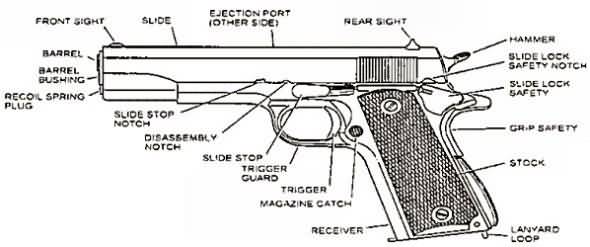

M1911A1 .45 Caliber Pistol

Widely used in World War I, World War II, the Korean War, and the Vietnam War, as of 1940 the original Model of 1911 was designated "Automatic Pistol, Caliber .45, M1911",, and "Automatic Pistol, Caliber .45, M1911A1" for the M1911A1 adopted in 1924. The classic M1911 pistol has now served the U.S. military for 88 years, but first came into its own during the Great War.

M1911A1 .45 Caliber Pistol

Norm White

Curatorial Assistant, National Firearms Museum

The Model 1911 and its progeny are perhaps the most successfully designed semi-automatic pistols in history. The brainchild of noted designer John Moses Browning, this legendary pistol has been widely copied both in the United States and abroad. A favorite of competitors and recreational shooters, the M1911 first established its reputation as a military arm, serving as the U.S. Army's standard sidearm for nearly 75 years and seeing action in every American conflict from the Mexican Punitive Expedition of 1916 through Operation Desert Storm. It has also served various law enforcement agencies and continues in that role today, having recently been selected for use by the Federal Bureau of Investigation's elite Hostage Rescue Team.

Despite how famous the M1911 has become, its service life began modestly. On April 24, 1911, the Army placed an initial order with Colt for 31,344 pistols. By early 1917, more than 100,000 had been manufactured both by Colt and by Springfield Armory under a licensing agreement. Most of these were issued to commissioned and noncommissioned officers, cavalrymen, and members of machine gun, artillery, and other crew-served weapons units. In addtion, about 18,000 were procured by the Navy and Marine Corps. Thousands more were purchased by various foreign governments, while others were sold to U.S. military officers and government officials, or on commercial markets. Among the M1911s sold during the prewar years were a group of approximately 100 pistols purchased through Springfield Armory by National Rifle Association (NRA) Life Members and members of NRA-affiliated clubs. Both Colt- and Springfield Armory-produced examples were included in this program. These pistols carried a purchase price of $16 each and were stamped with the letters "NRA" on the right side of the frame below the serial number.

Earlier government purchases had been sufficient for a peacetime army, but were woefully inadequate for a world at war. As the possibility loomed of American involvement in the European conflict, the War Department increased its orders for all types of military arms and supplies. Officials reported that approximately 70,000 M1911s were avilable for issue to U.S. troops when Congress declared war against the Central Powers on April 6, 1917, and the Army's Ordnance Department soon ordered an additional 500,000 pistols from Colt at a price of $14.50 each. To supplement this purchase, the Army also placed orders with both Colt and Smith & Wesson for 100,000 Model 1917 .45 caliber double-action revolvers. By the end of the war, more than 250,000 revolvers had been acquired by the government, and most were issued to officers and troops in rear areas.

Pistols became a much sought-after commodity among American soldiers as they took their places with the Allied forces in France. Patrols and trench raids frequently resulted in close-in or even hand-to-hand fighting between opposing troops. Excelling in both offensive and defensive roles, the rugged, hard-hitting Browning-Colt .45s quickly proved their worth. In one of the most famous incidents of the war, Sergeant Alvin C. York successfully engaged and silenced multiple German machine gun crews while armed only with a rifle and an M1911. Less than a week later, First Lieutenant Samuel Woodfill performed a similar feat. Both were awarded the Medal of Honor for their gallantry in action.

As the war progressed, Army estimates for the number of pistols it required were continually revised to meet increasing demands. After the gun's success in the trenches of France, the Army decided to supply the M1911 in greater numbers to infantry troops. During October 1917, government orders for the .45 autoloaders reached 765,000, an increase of nearly 60 percent. A critical situation arose as demands exceeded both available supplies and production efforts. For several reasons, Colt was only able to fill about 25 percent of its monthly quota for the M1911, and its backlog continued to grow. In addition to contracts for these pistols and for M1917 revolvers, the Hartford arms maker was producing both Vickers and Browning machine guns, as well as Browning Automatic Rifles, and the company had also agreed to rebuild or refurbish thousands of unserviceable .45 pistols and revolvers in military inventories. Production problems were further complicated by shortages of both skilled workers and raw materials.

Hoping to find an expedient but temporary solution to this problem, the government appealed to the public to turn in their commercially purchased Colt Government Model .45 autos for military use. Very few citizens responded to this call. Faced with a growing shortage and no immediate solutions, the Army began to investigate the possibility of expanding M1911 production by issuing additional contracts to other manufacturers.

In late 1917 and early 1918, the government approached both Remington-U.M.C. and Winchester Repeating Arms Co. about manufacturing the M1911. Remington-U.M.C.'s Bridgeport, Connecticut plant was the largest in the United States at that time, and production lines at the 1.6 million square-foot complex were turning out a variety of arms, including the M1917 bolt-action rifles and Browning .50 caliber machine guns, as well as the M1891 Mosin-Nagant rifles for the Russian government. In nearby New Haven, Winchester also produced M1917 rifles, in addition to Browning Automatic Rifles and M1897 trench shotguns. Both companies received contracts for 500,000 M1911s. Under terms of their agreements, pistols manufactured by these two firms were to be completely interchangeable with those produced by Colt and Springfield Armory.

However, while Colt provided technical assistance in the form of sample pistols and production drawings, problems quickly arose. In addition to numerous discrepancies, these drawings contained only nominal dimensions and no tolerances.

In order to enable Winchester to channel its efforts toward production of other urgently needed arms, the Chief of Ordnance recommended that Winchester's contract for the M1911 be transferred elsewhere. Though the company's quota was cut from 500,000 to 100,000, the agreement remained in effect until December 4, 1918. No completed pistols were produced, and Winchester later transferred all parts and assemblies then on hand to Springfield Armory.

Finding it easier to make their own blueprints based on measurements obtained from the Colt-produced sample pistols rather than reconcile more than 400 known discrepancies, Remington-U.M.C. created a set of "salvage drawings" that were later used by other contractors as well. The Army suspended its contract with Remington-U.M.C. on December 12, 1918, but allowed the company to manufacture additional examples to reduce its inventories of various parts on hand. All told, nearly 22,000 M1911s were delivered to the government before Remington-U.M.C. shut down its production line. In the summer of 1919, the company turned over its pistol manufacturing equiement to Springfield ARmory, where it was placed in storage until the Second World War.

In addition to Colt, Remington-U.M.C., and winchester, the Army also issued contracts to several other companies, including North American Arms Co. (Quebec, Canada), A.J. Savage Munitions Co. (San Diego), National Cash Register Co. (Dayton, Ohio), Lanston Monotype Co. (Philadelphia), Caron Brothers Manufacturing Co. (Montreal, Canada), Savage Arms Co. (Utica, NY), and Burroughs Adding Machine Co. (Detroit, Mich). Most of these contracts were issued during the final three months of the war, and all outstanding pistol orders were canceled by early 1919. While some were able to produce parts and assemblies, only Colt, Remington-U.M.C., and North American Arms succeeded in manufacturing completed pistols.

The North American Arms Co., which was organized and incorporated on June 28, 1918, secured a contract from the U.S. Army to manufacture the M1911 in place of the defunct Ross Rifle Co. of Quebec. At the outbreak of war in 1914, Ross was producing the Canadian Army's standard straight-pull rifle, but combat use proved these arms to be unsatisfactory. Canadian troops switched to British made Enfields, and the Ross Rifle Co. eventually went out of business. North American's contract of July 1, 1918, called for the productin of 500,000 pistols at a price of $15 (U.S.) each, and the U.S. government agreed to furnish raw materials in return for reimbursement through deductions on invoices for finished pistols. Lacking its own production facilities, North American leased the former Ross Rifle plant for this purpose. The Army canceled its contract with North American Arms on December 4, 1918, just as the first prototypes were being assembled. No pistols were delivered to U.S. authorities, but approximately 100 toolroom samples were produced. These are among the rarest of all M1911 pistols in existence.

There is much conflicting information regarding the wartime manufacture of .45 auto pistols at Springfield Armory, with some sources indicating that as many as 45,000 were produced there in 1918. Prior to U.S. entry into the war, Springfield Armory had produced the M1911 under license from Colt, but the M1903 rifle had become Springfield's chief product by 1917. The armory had no separate facilities for the manufacture of rifles and pistols, and as the demand for rifles rose in the spring of 1918, the Ordnance Department approved a request by Springfield Armory's commanding officer to convert the plant for rifle production. In addition, annual reports from Springfield indicate that fewer than 2,5000 M1911s were produced in 1917, but make no mention of the production of completed pistols during the following year.

Between May 1917 and October 1918, the government contracted for the production of more than 2.7 million M1911 pistols. By the war's end, more than 500,000 had been delivered at an average cost of $15 each. Though the final tally fell far short of the millions of pistols ordered by the Army, those that were produced provided American soldiers with an effective close range personal defense arm. Many of these pistols were "casualties of war," with some being destroyed, lost, or captured, while thousands more were "appropriated" by the soldiers who used them and the brought them home as souvenirs of their service abroad

The Armistice did not bring an end to fighting for all U.S. troops. After Russia signed a separate peace with the Kaiser in early 1918, the Allies organized expeditionary forces made up of 100,000 troops from 14 countries, including 10,000 Americans, and dispatched them to northern Russia and Siberia, ostensibly to secure railheads and safeguard stockpiled war materiel against seizure by German troops. Fighting both hostile Red Army units and temperatures as low as -60 degrees, more than 700 U.S. troops were killed or wounded before they were withdrawn in January 1920.

During the final year of what came to be known as the Great War, the Model 1911 saw widespread use in the hands of American servicemen, during which time these arms first carved a place in the annals of U.S. military history. Among the Model 1911 pistols on display at the National Firearms Museum in Fairfax, Va, are two Colt-produced examples, one of which bears U.S. Navy markings and the other, featuring ornately-carved wooden grips, was carried by a U.S. officer in the Siberian Expedition. Other M1911s in the museum colleciton include a REmington-U.M.C. model, a rare Springfield-produced, NRA-marked example, and an equally rare North American Arms toolroom prototype bearing the date of December 7, 1918 on the right side of the slide.

Exactly 23 years later, Japanese pilots attacked the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor. The events of that "Day of Infamy" brought the United States into the Second World War, a conflict in which the legend of the Colt .45 auto would continue to grow.