|

|

CHAPTER IVThe United States and the United Nations React |

The Foundation of Freedom is the Courage of Ordinary PeopleHistory |

| Thus we see that war is not only a political act, but a true instrumentof politics, a continuation of politics by other means. |

| CARL VON CLAUSEWITZ, On War |

The first official word of the North Korean attack across the borderinto South Korea reached Tokyo in an information copy of an emergency telegramdispatched from Seoul at 0925, 25 June, by the military attachéat the American Embassy there to the Assistant Chief of Staff, G-2, Departmentof the Army, in Washington. [1] About the same time the Far East Air Forcesin Tokyo began receiving radio messages from Kimpo Airfield near Seoulstating that fighting was taking place along the 38th Parallel on a scalethat seemed to indicate more than the usual border incidents. NorthwestAirlines, with Air Force support, operated Kimpo Airfield at this time.Brig. Gen. Jared V. Crabb, Deputy Chief of Staff for Far East Air Forces,telephoned Brig. Gen. Edwin K. Wright, Assistant Chief of Staff, G-3, FarEast Command, about 1030 and the two compared information. Thereafter throughoutthe day the two men were in constant communication with each other on thedirect line they maintained between their offices. Most of the messagesto Tokyo during 25 June came to the U.S. Air Force from Kimpo Airfield,and there was a constant stream of them. By 1500 in the afternoon bothCrabb and Wright were convinced that the North Koreans were engaged ina full-scale invasion of South Korea. [2]

About the time the military attaché in Seoul sent the first messageto the Department of the Army, representatives of press associations inKorea began sending news bulletins to their offices in the United States.It was about eight o'clock Saturday night, 24 June, Washington time, whenthe first reports reached that city of the North Korean attacks that hadbegun five hours earlier. Soon afterward, Ambassador Muccio sent his firstradio message from Seoul to the Department of State, which received itat 9:26 p.m., 24 June. This would correspond to 10:26 a.m., 25 June, in Korea. Ambassador Muccio said in part, "It wouldappear from the nature of the attack and the manner in which it was launchedthat it constitutes an all-out offensive against the Republic of Korea."[3]

The North Korean attack surprised official Washington. Maj. Gen. L.L. Lemnitzer in a memorandum to the Secretary of Defense on 29 June gavewhat is undoubtedly an accurate statement of the climate of opinion prevailingin Washington in informed circles at the time of the attack. He said ithad been known for many months that the North Korean forces possessed thecapability of attacking South Korea; that similar capabilities existedin practically every other country bordering the USSR; but that he knewof no intelligence agency that had centered attention on Korea as a pointof imminent attack. [4] The surprise in Washington on Sunday, 25 June 1950,according to some observers, resembled that of another, earlier Sunday-PearlHarbor, 7 December 1941.

U.S. and U.N. Action

When Trygve Lie, Secretary-General of the United Nations, at his LongIsland home that night received the news of the North Korean attack hereportedly burst out over the telephone, "This is war against theUnited Nations." [5] He called a meeting of the Security Council forthe next day. When the Council met at 2 p.m., 25 June (New York time),it debated, amended, and revised a resolution with respect to Korea andthen adopted it by a vote of nine to zero, with one abstention and oneabsence. Voting for the resolution were China, Cuba, Ecuador, Egypt, France,India, Norway, the United Kingdom, and the United States. Yugoslavia abstainedfrom voting; the Soviet Union was not represented. The Soviet delegatehad boycotted the meetings of the Security Council since January 10, 1950,over the issue of seating Red China's representative in the United Nationsas the official Chinese representative. [6]

The Security Council resolution stated that the armed attack upon theRepublic of Korea by forces from North Korea "constitutes a breachof the peace." It called for (1) immediate cessation of hostilities;(2) authorities of North Korea to withdraw forthwith their armed forcesto the 38th Parallel; and, finally, "all Members to render every assistanceto the United Nations in the execution of this resolution and to refrainfrom giving assistance to the North Korean authorities." [7]

President Truman had received the news at his home in Independence,Mo. He started back to Washington by plane in the early afternoon of 25June. At a meeting in Blair House that night, with officials of the State and Defense Departments present, President Trumanmade a number of decisions. The Joint Chiefs of Staff established a teletypeconference with General MacArthur in Tokyo at once and relayed to him PresidentTruman's decisions. They authorized General MacArthur to do the following:(1) send ammunition and equipment to Korea to prevent loss of the Seoul-Kimpoarea with appropriate air and naval cover to assure their safe arrival;(2) provide ships and planes to evacuate American dependents from Koreaand to protect the evacuation; and (3) dispatch a survey party to Koreato study the situation and determine how best to assist the Republic ofKorea. President Truman also ordered the Seventh Fleet to start from thePhilippines and Okinawa for Sasebo, Japan, and report to the Commander,U.S. Naval Forces, Far East (NAVFE), for operational control. [8]

In the evening of 26 June President Truman received General MacArthur'sreport that ROK forces could not hold Seoul, that the ROK forces were indanger of collapse, that evacuation of American nationals was under way,and that the first North Korean plane had been shot down. After a shortmeeting with leading advisers the President approved a number of measures.

Further instructions went to MacArthur in another teletype conferencethat night. They authorized him to use the Far East naval and air forcesin support of the Republic of Korea against all targets south of the 38thParallel. These instructions stated that the purpose of this action wasto clear South Korea of North Korean military forces. On 27 June, Far Easterntime, therefore, General MacArthur had authorization to intervene in Koreawith air and naval forces. [9]

During the night of 27 June the United Nations Security Council passeda second momentous resolution calling upon member nations to give militaryaid to South Korea in repelling the North Korean attack. After a statementon the act of aggression and the fruitless efforts of the United Nationsto halt it, the Security Council resolution ended with these fateful words:"Recommends that the Members of the United Nations furnishsuch assistance to the Republic of Korea as may be necessary to repel thearmed attack and to restore international peace and security in the area."[10]

Thus, events on the international stage by the third day of the invasionhad progressed swiftly to the point where the United States had authorizedits commander in the Far East to use air and naval forces below the 38thParallel to help repel the aggression and the United Nations had calledupon its member nations to help repel the attack. The North Koreans werenow in Seoul.

Evacuation of U.S. Nationals From Korea

From the moment United States KMAG officers in Korea and responsible officers in General MacArthur's Far East Command headquarters acceptedthe North Korean attack across the Parallel as an act of full-scale war,it became imperative for them to evacuate American women and children andother nonmilitary persons from Korea.

Almost a year earlier, on 21 July 1949, an operational plan had beendistributed by the Far East Command to accomplish such an evacuation bysea and by air. NAVFE was to provide the ships and naval escort protectionfor the water lift; the Far East Air Forces was to provide the planes forthe airlift and give fighter cover to both the water and air evacuationupon orders from the Commander in Chief, Far East. [11] By midnight, 25June, General Wright in Tokyo had alerted every agency concerned to beready to put the evacuation plan into effect upon the request of AmbassadorMuccio. [12] About 2200, 25 June, Ambassador Muccio authorized the evacuationof the women and children by any means without delay, and an hour laterhe ordered all American women and children and others who wished to leaveto assemble at Camp Sobinggo, the American housing compound in Seoul, fortransportation to Inch'on. [13]

The movement of the American dependents from Seoul to Inch'on beganat 0100, 26 June, and continued during the night. The last families clearedthe Han River bridge about 0900 and by 1800 682 women and children wereaboard the Norwegian fertilizer ship, the Reinholt, which had hurriedlyunloaded its cargo during the day, and was under way in Inch'on Harborto put to sea. At the southern tip of the peninsula, at Pusan, the shipPioneer Dale took on American dependents from Taejon, Taegu, andPusan. [14] American fighter planes from Japan flew twenty-seven escortand surveillance sorties during the day covering the evacuation.

On 27 June the evacuation of American and other foreign nationals continuedfrom Kimpo and Suwon Airfields at an increased pace. During the morning3 North Korean planes fired on four American fighters covering the airevacuation and, in the ensuing engagement, the U.S. fighters shot downall 3 enemy planes near Inch'on. Later in the day, American fighter planesshot down 4 more North Korean YAK-3 planes in the Inch'on-Seoul area. During27 June F-80 and F-82 planes of the 68th and 338th All-Weather FighterSquadrons and the 35th Fighter-Bomber Squadron of the Fifth Air Force flew163 sorties over Korea. [15]

During the period 26-29 June sea and air carriers evacuated a totalof 2,001 persons from Korea to Japan. Of this number, 1,527 were U.S. nationals-718of them traveled by air, 809 by water.

The largest single group of evacuees was aboard the Reinholt.

KMAG Starts To Leave Korea

On Sunday, 25 June, while Colonel Wright, KMAG Chief of Staff, was inchurch in Tokyo (he had gone to Japan to see his wife, the night before,board a ship bound for the United States, and expected to follow her ina few days), a messenger found him and whispered in his ear, "Youhad better get back to Korea." Colonel Wright left church at onceand telephoned Colonel Greenwood in Seoul. Colonel Wright arrived at Seoulat 0400, Monday, after flying to Kimpo Airfield from Japan. [16]

Colonel Wright reached the decision, with Ambassador Muccio's approval,to evacuate all KMAG personnel from Korea except thirty-three that ColonelWright selected to remain with the ROK Army headquarters. Most of the KMAGgroup departed Suwon by air on the 27th. Strangely enough, the last evacuationplane arriving at Kimpo that evening from Japan brought four correspondentsfrom Tokyo: Keyes Beech of the Chicago Daily News, Burton Craneof the New York Times, Frank Gibney of Time Magazine, andMarguerite Higgins of the New York Herald-Tribune. They joined aKMAG group that returned to Seoul. In the east and south of Korea, meanwhile,some fifty-six KMAG advisers by 29 June had made their way to Pusan wherethey put themselves under the command of Lt. Col. Rollins S. Emmerich,KMAG adviser to the ROK 3d Division. [17]

Shortly after midnight of 26 June the State Department ordered AmbassadorMuccio to leave Seoul and, accordingly, he went south to Suwon the morningof the 27th. [18] Colonel Wright with his selected group of advisers followedthe ROK Army headquarters to Sihung on the south side of the river. ColonelWright had with him the KMAG command radio, an SCR-399 mounted on a 2 1/2-tontruck. Soon after crossing the Han River en route to Sihung Colonel Wrightreceived a radio message from General MacArthur in Tokyo stating that theJoint Chiefs of Staff had directed him to take command of all U.S. militarypersonnel in Korea, including KMAG, and that he was sending an advancecommand and liaison group from his headquarters to Korea. [19] After hearrived at Sihung, Colonel Wright received another radio message from GeneralMacArthur, intercepted by the radio station at Suwon Airfield. It saidin effect, "Personal MacArthur to Wright: Repair to your former locations.Momentous decisions are in the offing. Be of good cheer." [20] Aidedby the import of these messages, Colonel Wright persuaded General Chaeto return the ROK Army headquarters to Seoul that evening.

That night the blowing of the Han River bridges cut off the KMAG groupin Seoul. Colonel Wright had had practically no rest since Sunday and,accompanied by Lt. Col. William J. Mahoney, he had retired to his quartersbefore midnight to get some sleep. Beginning about 0100, 28 June, KMAGofficers at ROK Army headquarters tried repeatedly to telephone him theinformation that the ROK Army headquarters was leaving Seoul. This wouldnecessitate a decision by Colonel Wright as to whether KMAG should alsoleave. But the telephone message never got to Colonel Wright because ColonelMahoney who took the calls refused to disturb him. Finally, after the ROKArmy headquarters staff had departed, Lt. Col. Lewis D. Vieman went toColonel Wright's quarters for the second time, found the houseboy, andhad him awaken Colonel Wright. Colonel Vieman then informed Colonel Wrightof the situation. [21]

The latter was just leaving his quarters when the Han River bridgesblew up. Colonel Wright assembled all the Americans in a convoy and startedfor a bridge east of the city. [22] En route they learned from Korean soldiersthat this bridge too had been blown. The convoy turned around and returnedto the KMAG housing area at Camp Sobinggo. About daylight a small reconnaissanceparty reported that ferries were in operation along the Han River eastof the highway bridge. At this juncture Lt. Col. Lee Chi Yep, a memberof the ROK Army staff, long friendly with the Americans and in turn highlyregarded by the KMAG advisers, walked up to them. He volunteered to helpin securing ferry transportation across the river.

Upon arriving at the river bank, Colonel Wright's party found a chaoticmelee. ROK soldiers and unit leaders fired at the boatmen and, using threats,tried to commandeer transportation from among the ferries and various kindsof craft engaged in transporting soldiers and refugees across the river.Colonel Lee adopted this method, persuading a boatman to bring his craftalongside by putting a bullet through the man's shirt. It took about twohours for the party to make the crossing. Colonel Wright, two other officers,and two or three enlisted men stayed behind and finally succeeded in gettingthe command radio vehicle across the river. It provided the only communicationthe KMAG group had with Japan, and Colonel Wright would not leave it behind.Enemy artillery fire was falling some distance upstream and tank fire haddrawn perceptibly closer when the last boatload started across the river.[23]

After reaching the south bank, about 0800, the KMAG party struck outand walked the 15-mile cross-country trail to Anyang-ni, arriving thereat 1500, 28 June. Waiting vehicles, obtained by an advance party that hadgone ahead in a jeep, picked up the tired men and carried them to Suwon.Upon arriving at Suwon they found Colonel Wright and his command radio already there. After Although in the first few dayssome getting across the river Wright had members of the KMAG group reportturned through Yongdungp'o, which, contrary to rumors, proved to be freeof enemy and had then traveled the main road. [24]

Although in the first few days some members of the KMAG group reportedlywere cut off and missing, all reached safety by the end of the month, andup to 5 July only three had been slightly wounded. [25]

ADCOM in Korea

General MacArthur as Commander in Chief, Far East, had no responsibilityin Korea on 25 June 1950 except to support KMAG and the American Embassylogistically to the Korean water line. This situation changed when PresidentTruman authorized him on 26 June, Far Eastern Time, to send a survey party to Korea.

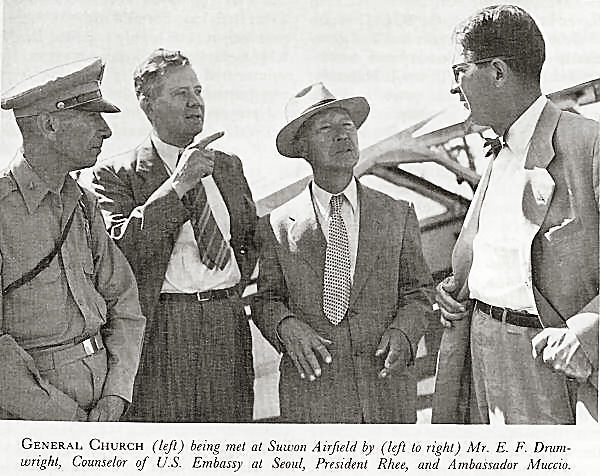

General MacArthur formed at once a survey party of thirteen GHQ Generaland Special Staff officers and two enlisted men, headed by Brig. Gen. JohnH. Church. Its mission upon arrival in Korea was to help Ambassador Muccioand KMAG to determine logistical requirements for assisting the ROK Army.The party left Haneda Airfield at 0400, 27 June, and arrived at ItazukeAir Base in southern Japan two hours later. While there awaiting furtherorders before proceeding to Seoul, General Church received telephone instructionsfrom Tokyo about 1425 changing his destination from Seoul to Suwon becauseit was feared the former might be in enemy hands by the time he got there.MacArthur had by this time received the Joint Chiefs of Staff directivewhich instructed him to assume operational control of all U.S. militaryactivities in Korea. Accordingly, he redesignated the survey group as GHQAdvance Command and Liaison Group in Korea (ADCOM), and gave it an expandedmission of assuming control of KMAG and of lending all possible assistanceto the ROK Army in striving to check the Red drive southward. [26]

The ADCOM group arrived at Suwon Airfield at 1900, 27 June, where AmbassadorMuccio met it. General Church telephoned Colonel Wright in Seoul, who advisedhim not to come into the city that night. The ADCOM group thereupon setup temporary headquarters in the Experimental Agriculture Building in Suwon.[27]

The next day about 0400 Colonel Hazlett and Captain Hausman, KMAG advisers,arrived at Suwon from Seoul. They told General Church that the Han Riverbridges were down, that some North Korean tanks were in Seoul, that theSouth Korean forces defending Seoul were crumbling and fleeing toward Suwon,and that they feared the majority of KMAG was still in Seoul and trappedthere. [28] Such was the dark picture presented to General Church beforedawn of his first full day in Korea, 28 June.

General Church asked Hazlett and Hausman to find General Chae, ROK Chiefof Staff. Several hours later General Chae arrived at ADCOM headquarters.Church told him that MacArthur was in operational control of the Americanair and naval support of the ROK forces, and that the group at Suwon washis, MacArthur's, advance headquarters in Korea. At Church's suggestionChae moved the ROK Army headquarters into the same building with Church'sADCOM headquarters.

General Church advised General Chae to order ROK forces in the vicinityof Seoul to continue street fighting in the city; to establish stragglerpoints between Seoul and Suwon and to collect all ROK troops south of the HanRiver and reorganize them into units, and to defend the Han River lineat all cost. [29] During the day, KMAG and ROK officers collected about1,000 ROK officers and 8,000 men and organized them into provisional unitsin the vicinity of Suwon. General Chae sent them back to the Han River.

General Church sent a radio message to General MacArthur on the 28th,describing the situation and stating that the United States would haveto commit ground troops to restore the original boundary line. [30] Thatevening he received a radio message from Tokyo stating that a high-rankingofficer would arrive the next morning and asking if the Suwon Airfieldwas operational. General Church replied that it was.

MacArthur Flies to Korea

The "high-ranking officer" mentioned in the radio messageof the 28th was General of the Army Douglas MacArthur. Shortly before noonon 28 June, General MacArthur called Lt. Col. Anthony F. Story, his personalpilot, to his office in the Dai Ichi Building in Tokyo and said he wantedto go to Suwon the next day to make a personal inspection. Colonel Storychecked the weather reports and found them negative-storms, rains, lowceiling, and heavy winds predicted for the morrow. [31]

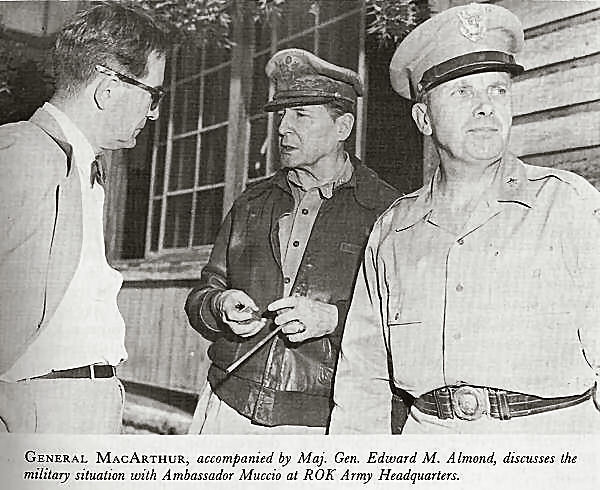

At 0400, 29 June, MacArthur was up and preparing for the flight to Suwon.At 0600 he arrived at Haneda and, with the assembled group, climbed aboardthe Bataan, his personal C-54 plane. A total of fifteen individualsmade the trip, including seven high-ranking officers of General MacArthur'sstaff. Rain was falling when the Bataan took off from Haneda at0610. About 0800 General MacArthur dictated a radiogram to Maj. Gen. EarlE. Partridge, commanding FEAF in Lt. Gen. George E. Stratemeyer's absence.General Stratemeyer wrote it out and handed it to Story to send. It said,"Stratemeyer to Partridge: Take out North Korean Airfield immediately.No publicity. MacArthur approves." [32]

The weather had now improved sufficiently to permit fighter planes totake off, and at 1000 four of them intercepted and escorted the Bataanto Suwon. That morning North Korean fighter planes had strafed theSuwon Airfield and set on fire a C-54 at the end of the runway. This wreckedplane constituted a 20-foot obstacle on an already short runway, but ColonelStory succeeded in setting the Bataan down without mishap. Waitingat the airfield were President Rhee, Ambassador Muccio, and General Church.The party got into an old black sedan and drove to General Church's headquarters.In the conversation there Church told MacArthur that that morning not morethan 8,000 ROK's could be accounted for; that at that moment, noon, theyhad 8,000 more; and that by night he expected to have an additional 8,000; therefore at day's end they could count on about 25,000. [33]

Colonel Story, in the meantime, took off from the Suwon Airfield at1130 and flew to Fukuoka, Japan where he refueled and made ready to returnto Suwon. During the afternoon North Korean planes bombed the Suwon Airfieldand a YAK fighter destroyed a recently arrived C-47 plane. [34]

General MacArthur insisted on going up to the Han River, opposite Seoul,to form his own impression of the situation. On the trip to and from theHan, MacArthur saw thousands of refugees and disorganized ROK soldiersmoving away from the battle area. He told General Church that in his opinionthe situation required the immediate commitment of American ground forces.He said he would request authority from Washington that night for suchaction. [35]

Colonel Story brought the Bataan back to Suwon at 1715. Withinan hour General MacArthur was on his way back to Japan.

Other than KMAG and ADCOM personnel, the first American troops to goto Korea arrived at Suwon Airfield on 29 June, the day of MacArthur's visit.The unit, known as Detachment X, consisted of thirty-three officers andmen and four M55 machine guns of the 507th Antiaircraft Artillery (AutomaticWeapons) Battalion. At 1615 they engaged 4 enemy planes that attacked theairfield, shooting down 1 and probably destroying another, and again at2005 that evening they engaged 3 planes. [36]

The President Authorizes Use of U.S. Ground Troops in Korea

Reports coming into the Pentagon from the Far East during the morningof 29 June described the situation in Korea as so bad that Secretary ofDefense Louis A. Johnson telephoned President Truman before noon. In ameeting late that afternoon the President approved a new directive greatlybroadening the authority of the Far East commander in meeting the Koreancrisis.

This directive, received by the Far East commander on 30 June, Tokyotime, authorized him to (1) employ U.S. Army service forces in South Koreato maintain communications and other essential services; (2) employ Armycombat and service troops to ensure the retention of a port and air basein the general area of Pusan-Chinhae; (3) employ naval and air forces againstmilitary targets in North Korea but to stay well clear of the frontiersof Manchuria and the Soviet Union; (4) by naval and air action defend Formosaagainst invasion by the Chinese Communists and, conversely, prevent ChineseNationalists from using Formosa as a base of operations against the Chinesemainland; (5) send to Korea any supplies and munitions at his disposaland submit estimates for amounts and types of aid required outside hiscontrol. It also assigned the Seventh Fleet to MacArthur's operationalcontrol, and indicated that naval commanders in the Pacific would supportand reinforce him as necessary and practicable. The directive ended witha statement that the instructions did not constitute a decision to engagein war with the Soviet Union if Soviet forces intervened in Korea, butthat there was full realization of the risks involved in the decisionswith respect to Korea. [37] It is to be noted that this directive of 29June did not authorize General MacArthur to use U.S. ground combat troopsin the Han River area-only at the southern tip of the peninsula to assurethe retention of a port.

Several hours after this portentous directive had gone to the Far EastCommand, the Pentagon received at approximately 0300, 30 June, GeneralMacArthur's report on his trip to Korea the previous day. This report describedthe great loss of personnel and equipment in the ROK forces, estimatedtheir effective military strength at not more than 25,000 men, stated thateverything possible was being done in Japan to establish and maintain aflow of supplies to the ROK Army through the Port of Pusan and Suwon Airfield,and that every effort was being made to establish a Han River line but the result was problematical. MacArthur concluded:

The only assurance for the holding of the present line, and the abilityto regain later the lost ground, is through the introduction of U.S. groundcombat forces into the Korean battle area. To continue to utilize the forcesof our Air and Navy without an effective ground element cannot be decisive.

If authorized, it is my intention to immediately move a U.S. regimentalcombat team to the reinforcement of the vital area discussed and to providefor a possible build-up to a two division strength from the troops in Japanfor an early counteroffensive. [38]

General J. Lawton Collins, Army Chief of Staff, notified Secretary ofthe Army Frank Pace, Jr., of MacArthur's report and then established ateletype connection with MacArthur in Tokyo. In a teletype conversationMacArthur told Collins that the authority already given to use a regimentalcombat team at Pusan did not provide sufficient latitude for efficientoperations in the prevailing situation and did not satisfy the basic requirementsdescribed in his report. MacArthur said, "Time is of the essence anda clear-cut decision without delay is essential." Collins repliedthat he would proceed through the Secretary of the Army to request Presidentialapproval to send a regimental combat team into the forward combat area,and that he would advise him further, possibly within half an hour. [39]

Collins immediately telephoned Secretary Pace and gave him a summaryof Secretary Pace in turn telephoned the President at Blair House. PresidentTruman, already up, took the call at 0457, 30 June. Pace informed the Presidentof MacArthur's report and the teletype conversations just concluded. PresidentTruman approved without hesitation sending one regiment to the combat zoneand said he would give his decision within a few hours on sending two divisions.In less than half an hour after the conclusion of the MacArthur-Collinsteletype conversations the President's decision to send one regiment tothe combat zone was on its way to MacArthur. [40]

At midmorning President Truman held a meeting with State and DefenseDepartment officials and approved two orders: (1) to send two divisionsto Korea from Japan; and (2) to establish a naval blockade of North Korea.He then called a meeting of the Vice President, the Cabinet, and Congressionaland military leaders at the White House at 1100 and informed them of theaction he had taken.

That afternoon Delegate Warren Austin addressed the Security Councilof the United Nations telling them of the action taken by the United Statesin conformity with their resolutions of 25 and 27 June. On the afternoonof 30 June, also, the President announced his momentous decision to theworld in a terse and formal press release. [41]

The die was cast. The United States was in the Korean War.

Meanwhile, the Secretary-General of the United Nations on 29 June hadsent a communication to all member nations asking what type of assistancethey would give South Korea in response to the Security Council resolutionof 27 June. Three members-the Soviet Union, Poland, and Czechoslovakia-declaredthe resolution illegal. Most of the others promised moral or material support.Material support took the form chiefly of supplies, foodstuffs, or servicesthat were most readily available to the particular countries.

The United Kingdom Defense Committee on 28 June placed British navalforces in Japanese waters (1 light fleet carrier, 2 cruisers, and 5 destroyersand frigates) under the control of the U.S. naval commander. This navalforce came under General MacArthur's control the next day. On 29 June,the Australian Ambassador called on Secretary of State Dean Acheson andsaid that his country would make available for use in Korea a destroyerand a frigate based in Japan, and that a squadron of short-range Mustangfighter planes (77th Squadron Royal Australian Air Force) also based inJapan would be available. [42] Canada, New Zealand, and the Netherlandssaid they were dispatching naval units.

Only Nationalist China offered ground troops-three divisions totaling33,000 men, together with twenty transport planes and some naval escort.General MacArthur eventually turned down this offer on 1 August becausethe Nationalist Chinese troops were considered to be untrained and hadno artillery or motor transport.

[1] Schnabel, FEC, GHQ Support and Participation in Korean War, ch. II,

[2] Ltr, Gen Wright to author, 12 Feb 54.

[3] This radio message is reproduced in full in Dept of State Pub 3922, United States Policy in the Korean Crisis, Doc. 1, p. 11.

[4] Memo, Maj Gen L. L. Lemnitzer, Director, Off of Mil Assistance, for Secy Defense, 29 Jun 50; S. Comm. on Armed Services and S. Comm. on Foreign Relations, 82d Cong., 1st Sess., 1951, Joint Hearings, Military Situation in the Far East (MacArthur Hearings), pt. III, pp. 1990-92, Testimony of Secretary of State Acheson.

[5] Albert L. Warner, "How the Korea Decision was Made," Harper's Magazine, June 26, 1950, pp. 99-106; Beverly Smith, "Why We Went to War in Korea," Saturday Evening Post, November 10, 1951.

[6] United States Policy in the Korean Crisis, p. 1, n. 5, and Docs. 3, 4, and 5, pp. 12-16.

[7] Ibid., Doc. 5, p. 16.

[8] Telecon TT3418, 25 Jun 50. For a detailed discussion of the Department of the Army and Far East Command interchange of views and instructions concerning the Korean crisis and later conduct of the war following intervention see Maj James F. Schnabel, Theater Command.

[9] Telecon TT3426, 27 Jun 50.

[10] United States Policy in the Korean Crisis, p. 4, and Doc. 16, p. 24: The vote was seven in favor, one opposed, two abstentions, and one absence: the Soviet Union was absent. Two days later India accepted the resolution. See Doc. 52, pp. 42-43.

[11] Schnabel, FEC, GHQ Support and Participation in the Korean War, ch. II, pp. 11-12.

[12] Ltr, Gen Wright to author, 12 Feb 54.

[13] Sawyer, KMAG MS; John C. Caldwell, The Korea Story (Chicago: H. Regnery Co., 1952), p. 170.

[14] Sawyer, KMAG MS; Statement, Greenwood for Sawyer, 22 Feb 54.

[15] GHQ FEC, Ann Narr Hist Rpt, 1 Jan-31 Oct 50, pp. 8-9; Capt Robert L. Gray, Jr., "Air Operations Over Korea," Army Information Digest, January 1952, p. 17; USAF Opns in the Korean Conflict, 25 Jun-1 Nov 50, USAF Hist Study 71, pp. 5-6; 24th Div G-3 and G-2 Jnl Msg files, 27 Jun 50: New York Herald-Tribune, June 27, 1950.

[16] Sawyer, KMAG MS; Col Wright, Notes for author, 1952; Ltr, Gen Wright to author, 12 Feb 54; Statement, Greenwood for Sawyer.

[17] Wright, Notes for author; Statement, Greenwood for Sawyer: Sawyer, KMAG MS; Ltr, Rockwell to author, 21 May 54; Ltr, Scott to friend, ca. 6-7 Jul 50; Col Emmerich, MS review comments, 26 Nov 57.

[18] Msg 270136Z, State Dept to Supreme Commander, Allied Powers (U.S. Political Adviser), cited in Schnabel, FEC, GHQ Support and Participation in the Korean War, ch. 2, p. 17.

[19] Col Wright, Notes for author; Sawyer, KMAG MS.

[20] Col Wright, Notes for author; Gen MacArthur MS review comments, 15 Nov 57.

[21] Vieman, Notes on Korea, 15 Feb 51; Interv, author with Vieman, 15 Jun 54; Interv, author with Hausman, 12 Jan 52: Interv, author with Col Wright, 3 Jan 52; Ltr, Col George R. Seaberry, Jr., to Capt Sawyer, 22 Dec 53.

[22] Greenwood estimates there were 130-odd men in the convoy, other estimates are as low as sixty.

[23] Vieman, Notes on Korea, 15 Feb 51; Statement, Greenwood for Sawyer; Ltr, Maj Ray B. May to Capt Sawyer, 2, Apr 54; Ltr, Scott to friend; Marguerite Higgins, War in Korea (Garden City, N.Y.: Doubleday and Company, Inc., 1951), pp. 27-30.

[24] Vieman, Notes on Korea, 15 Feb 51; Higgins, War in Korea; Statement, Greenwood for Sawyer; Ltr, May to Sawyer, 23 Apr 54.

The British Minister to South Korea, Capt. Vyvyan Holt, members of his staff, and a few other British subjects remained in Seoul and claimed diplomatic immunity. Instead of getting it they spent almost three years in a North Korean prison camp. The North Koreans finally released Captain Holt and six other British subjects to the Soviets in April 1953 for return to Britain during the prisoner exchange negotiations. Two, Father Charles Hunt and Sister Mary Claire, died during the internment. See the New York Times, April 21 and 22, 1953; the Washington Post, April 10, 1953.

[25] Crawford, Notes on Korea.

[26] Gen Church, Memo for Record, ADCOM Activities in Korea, 27 Jun-15 July 1950, GHQ FEC G-3, Ann Narr Hist Rpt, 1 Jan-31 Oct 51, Incl 11, pt. III. The Church ADCOM document grew out of stenographic notes of an interview by Major Schnabel with General Church, 17 July 1950. General Church was not satisfied with the notes thus produced and rewrote the draft himself a few days later. This source will hereafter be cited as Church MS. Lt Col Olinto M. Barsanti (G-1 ADCOM Rep), contemporary handwritten notes on ADCOM activities; Interv, author with Col Martin L. Green, ADCOM G-3, 14 Jul 51: Schnabel, FEC, GHQ Support and Participation in the Korean War, ch. 2, pp. 18-19.

[27] Church MS; Barsanti Notes: Statement, Greenwood for Sawyer.

[28] Church MS; Interv, author with Col Robert T. Hazlett, 11 Jun 54; Interv, author with Hausman, 12 Jan 52.

[29] Church MS; Barsanti Notes.

[30] Church MS. Church gives the date as 27 June, but this is a mistake.

[31] Interv, Dr. Gordon W. Prange with Col Story, 19 Feb 51, Tokyo. Colonel Story referred to his logbook of the flight for the details related in this interview

[32] Ibid.

[32] Interv, Prange with Story; Church MS; Ltr, Lt Gen Edward M. Almond to author, 18 Dec 53. (Almond was a member of the party.)

[34] Interv, Prange with Story.

[35] Church MS; Ltr, Gen Wright to author, 8 Feb 54 (Wright was a member of the party.)

[36] Det X, 507th AAA AW Bn Act Rpt, 1 Jul 50.

[37] JCS 84681 DA (JCS) to CINCFE, 29 Jun 50; Schnabel, FEC, GHQ Support and Participation in the Korean War, ch. 2, p. 26; MacArthur Hearings, pt. I, pp. 535-36, Secy of Defense George C. Marshall's testimony; New York Times, May 12, 1951.

[38] Msg, CINCFE to JCS, 30 Jun 50.

[39] Schnabel, FEC, GHQ Support and Participation in the Korean War, ch. 2, pp. 27-R8, citing and quoting telecons.

[40] Ibid., ch. 2, p. 28.

[41] United States Policy in the Korean Crisis, Doc. 17, pp. 24-25, and Doc. 18, pp. 25-26; Smith, "Why We Went to War in Korea," op. cit.

[42] United States Policy in the Korean Crisis, Docs. 20-90, pp. 28-60.

|

|

- A VETERAN's Blog - |